When a wild indigenous food all-of-a-sudden becomes internationally desired we are quick to overlook the hefty price tag but what else are we overlooking?

Exotic fruits and vegetables from the Amazonian region have become an everyday ingredient in American homes. Take a stroll in a natural foods market like Whole Foods and you will see rows and rows of dried powders and bottled elixirs from the Amazon, with funny sounding names you’re not so sure how to pronounce. Or you may have noticed your favorite lotion now contains something called Buriti oil, that’s pronounced “bu-REE-chee” by the way. With promises of unmatched nutrients and the potential to revitalize and possibly cure you, the pull towards that acai smoothie is strong.

The healing powers of these foods are often exaggerated but they are not always unfounded. Studies have found many of these foods to be packed with phytochemicals, nutrients that can lead to improved health and that are seriously lacking in the standard american diet. The cancer institute has identified over 2000 plants from the tropics as being active against cancer in vitro (Ovadje et al. 2015). With all the intrigue surrounding these nutrient dense foods many of us want to experience first hand how these foods can benefit us.

| Plant classification | |

| Common name | Buriti |

| Family | Arecaceae |

| Genius | Mauritia |

| Species | flexuosa |

The Health Benefits of Buriti Oil

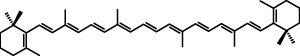

One of the latest buzzed about plants is Mauritia flexuosa, known in Brazil as Buriti. Buriti palm is the richest known sources of absorbable beta carotene, a precursor to vitamin A, with an astounding 19,500 mcg per 100g of Burtiti oil (Santos 2005). For a comparison the average carrot contains about 4,000 mcg per 100g. Many communities around the world struggle to get enough vitamin A in their diets. It is estimated that worldwide, malnutrition leads to one-third of the total deaths among children, with vitamin A being the most deficient nutrient (Akhta 2013). Buriti oil could have a role in making vitamin A more accessible. One study done in northeast Brazil showed that candy made from buriti oil given daily could correct vitamin A deficiency, in a relatively short amount of time. The complete test group of 44 children suffering from xerophthalmia, a condition that leads to blindness, no longer showed symptoms after a 20 day trial (Santos 2005). Buriti oil has shown to be a potentially life saving food in developing countries and it’s not surprising that interest from the west is also steadily increasing. What is surprising is we aren’t eating this extremely nutritious fruit, buriti oil in the states is almost exclusively found in cosmetics. That’s right, we decided the best use for this powerful food is to stay on the outside of our bodies.

Using Buriti oil in lotions might seem wasteful but it is not completely superfluous. Many studies are looking into the oils skin healing and UV blocking abilities (Zanatta et al. 2009). Buriti’s ability to block UV radiation and to combat free radicals is a defense that the plant has developed out of necessity. Full grown buriti palms can stand up to 40 m tall making them often the tallest tree of the Amazonian rainforest canopy. Without shade protection Buriti is able to combat the harshness of full sun in the tropics with the production of carotenoids. Carotenoids are plant pigment that protect cells against photooxidative damage by acting as an antioxidant (Zanatta et al. 2009). Studies using emulsions of buriti oil in sunscreens, revealed that some formulations decreased cell damage caused by the UVA and UVB radiation (Freire et al. 2016)

Beta Carotene

Keeping up with global demand

The global and local demand for Buriti has steadily increased since 1990 yet the harvesting techniques have roughly remained the same (Horn et al. 2011). Competition for the female fruiting trees is fierce and the fastest way to access the fruit is to chop the palm down. Traditional harvesting practices often involves felling the tallest most mature trees and about half of the Buriti palms harvested in 2010 were cut down rather than climbed (Horn et al. 2011). The elimination of female trees is leading to changes in the ecosystem that are still being investigated. A study done by (Horn et al. 2011) found female trees are becoming more scarce, the study found a 3.48:1 sex ratio of males to females and a trend in declining seedling. The decline in fruiting trees and the Buriti’s ability to reproduce means less of the nutritious fruits are available for the Tapirs, Red-belly Macaws and other wildlife that depend on Buriti as their primary source of nutrition. The bigger implications of the lost of these nutrients and habitats have not yet been fully investigated.

Red-bellied Macaws almost exclusively eat Buriti fruits and nest in the hollows of the tall dead palms .

With bioprospecting becoming less expensive many more of the health benefits contained in wild foods are being uncovered. These findings are exciting and could lead to life saving medical breakthroughs. The problem is when we deem something as the new superfood and therefore a valuable commodity, in a short amount of time we can disrupt delicate ecosystems that have taken millennia to evolve. Our individualistic quest for optimal health can come at a cost to the habitats and communities that rely on these plants as part of their daily lives .

References

Akhtar S. 2013. Prevalence of vitamin A deficiency in South Asia: causes, outcomes, and possible remedies. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 31.4: 413.

Bodmer, RE. 1990. Fruit patch size and frugivory in the lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris). Journal of Zoology. 222.1: 121-128.

Brightsmith, DJ. 2005. Parrot nesting in southeastern Peru: seasonal patterns and keystone trees.The wilson bulletin. 117.3: 296-305.

Freire, PJA. Barros, KBNT. Lima, LKF. Martins, JM. Araújo, YDC. Oliveira, GL. Aquino, J. Ferreira, PMP. 2016. Phytochemistry Profile, Nutritional Properties and Pharmacological Activities of Mauritia flexuosa. Journal of Food Science, 81(11).

Gujral S, Abbi R, Gopaldas T. 1993. Xerophthalmia, vitamin A supplementation and morbidity in children. Journal of tropical pediatrics.1;39(2):89-92.

Horn, CM. Gilmore, MP. Endress, BA. 2012. Ecological and socio-economic factors influencing aguaje (Mauritia flexuosa) resource management in two indigenous communities in the Peruvian Amazon. Forest Ecology and Management. 267, pp.93-103.

Ovadje P, Roma A, Steckle M, Nicoletti L, Arnason JT, Pandey S.2015. Advances in the research and development of natural health products as main stream cancer therapeutics. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 26;2015.

Santos, ML. 2005. Nutritional and ecological aspects of buriti or aguaje (Mauritia flexuosa Linnaeus filius): a carotene-rich palm fruit from Latin America. Ecology of food and nutrition. 44(5), pp.345-358.

Zanatta CF, Mitjans M, Urgatondo V, Rocha-Filho PA, Vinardell MP.2010. Photoprotective potential of emulsions formulated with Buriti oil (Mauritia flexuosa) against UV irradiation on keratinocytes and fibroblasts cell lines. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 48(1):70-5.