|

Family |

Plantaginaceae |

| Genus | Digitalis |

| Species | purpurea |

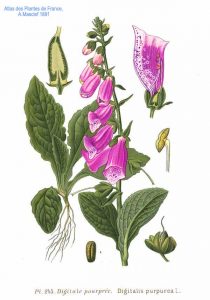

| Common Name | Foxglove |

During the height of summer in the Pacific Northwest, you’ll find roadsides, hiking trails, etc. decorated with towering purple to pink to white spikes. Growing up, I called these bee-loving plants foxglove. Now, with a little more botanical lexicon under my belt, the scientific name Digitalis purpurea gives me far more understanding of a plant that I have grown up along-side. Being the kid of a Wyoming-cowboy, the outdoors has been my home, classroom, and playground. Getting lost in a sea of purple was a wonderland to me, but I’m sure to my dad it seemed more like I was walking through a minefield. Upon finishing my frolicking, my dad put it simply: “The tastier a plant is, the more inconspicuous it has to be, because everyone wants to eat it, so if a plant is bright and eye-catching there is probably a reason it’s not scared of being eaten.”

Amédée Masclef, Atlas des plantes de France. 1891

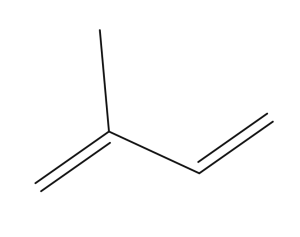

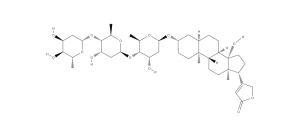

This is no exception for D. purpurea. The potentially lethal chemical that is found throughout the plant but in the highest abundance in the plant’s leaves is called digitoxin (Duke 2016). Ingestion of even just a small amount of the plant can cause vomiting, diarrhea, and an irregular heartbeat; larger doses can be fatal (Brunning 2015). Digitoxin is a cardenolide— or cardiac glycoside, which is a triterpene. This means that the building blocks that compose this compound consist of 30 carbons that form six isoprene units. Digitoxin occurs constitutively, being found in foxglove at any time, not just if the plant is under attack. The symptoms of digitoxin are caused by increased levels of sodium and calcium and a decrease in intracellular potassium.

Isoprene Unit – C5H8

The ecological function (the reason foxglove isn’t worried about being eaten) of digitoxin is to prevent herbivory. If eating just a little bit can cause an irregular heartbeat in humans and even death in children and the elderly, imagine what it could do to a tiny bug! Although the effects of digitoxin are toxic to most, the Monarch butterfly has developed a way to use this to its advantage. Monarchs are partial to milkweed, which also contains high amounts of cardiac glycosides. As caterpillars, the monarchs will feed on milkweed and safely sequester the toxin. When caterpillars molt, the toxin persist, deterring birds and other potential prey (Freeman 2008).

Although digitoxin can be lethal, it can also be lifesaving. The same chemical that causes irregular heartbeats in healthy individuals, can also treat abnormal heart arrhythmia and heart failure. It causes the heartbeat to slow down and increases the force in heart contractions resulting in an increased volume of blood (Digitalis). Digitoxin is the most commonly used purified glycoside, and D. purpurea is the principal source. In 1785, William Withering, who was both a botanist and a physician noted the medicinal properties of D. purpurea, specifically for the treatment of dropsy, an edema caused by congestive heart failure (Diefenbach 1949). Upon visiting a healer named Mrs. Hutton to evaluate her treatment for dropsy, Withering observed that foxglove was the key ingredient. He recorded in his report of Hutton’s remedy that “an old woman in Shropshire made cures after the more regular practitioners had failed” (Hogue 2005). Today, anyone suffering from heart failure, or simply just an X-files fanatic, will recognize digitoxin as the commonly proscribed pharmaceutical Digitalis, named after the genus of the plant it’s derived from.

Digitoxin”s structural formula C41H64O13

Reference List

Brunning, Andy. Chemistry of foxgloves – poison & medicine [Internet]. 2015. Compound Interest; [cited 2017 Jan 16]. Available from http://www.compoundchem.com/2016/06/21/foxgloves/

Diefenbach, William & Meneely, John. Digitoxin— a critical review [Internet]. 1949. National Center for Biotechnology Information. [cited 2017 Jan 21]. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2598854/pdf/yjbm00349-0056.pdf

Digitalis purpurea (common foxglove) [Internet]. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew. [cited 2017 Jan 16] Available from http://www.kew.org/science-conservation/plants-fungi/digitalis-purpurea-common-foxglove

Duke, James. Digitoxin [Internet]. 2016. Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Database; [cited 2017 Jan 16]. Available from https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/chemicals/show/7284

Freeman, B.C. and G.A. Beattie. An overview of plant defenses against pathogens and herbivores [Internet]. 2008. The Plant Health Instructor [cited 2017 Feb. 14] Available from http://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/intropp/topics/Pages/OverviewOfPlantDiseases.aspx

Hogue C. Digoxin [Internet]. 2005. Chemical & Engineering News: Top Pharmaceuticals: Digoxin. [cited 2017 Feb 15]. Available from https://pubs.acs.org/cen/coverstory/83/8325/8325digoxin.html

Lesney, Mark. Flowers for the heart [Internet]. 2002. American Chemical Society. [cited 2017 Feb. 24] Available from http://pubs.acs.org/subscribe/journals/mdd/v05/i03/html/03timeline.html