Breanna Strobele

Trigger Warning: This page addresses multiple issues that include suicide, and violence against women and children.

Regardless of one’s opinions about Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM), it is difficult to deny that the base has had a profound effect on the area around it. JBLM is one of the few U.S. military bases that is located in an urban area, which means it affects its surrounding communities more than most other bases. Some military publications have referred to JBLM as a “base on the brink” or the “most troubled base” in the military (Turner 2010; Murphy 2011). Deployments and stress have contributed to incidents of suicide, murder, drug overdoses, drunk driving, robberies, and domestic violence (Murphy 2011). These effects are exacerbated by Madigan Army Medical Center’s inability to care for all the soldiers that come back from deployment with mental health issues, such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). While most deployed servicemembers have not experienced these health and social crises directly, how the Army responds to social crises measures how it respects the personnel, their families, and their communities.

Health Crisis

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

PTSD can occur when someone either experiences or witnesses a traumatic event. Many people with PTSD have nightmares and flashbacks related to their trauma. It is common for someone with PTSD to also have depression, anxiety or substance abuse issues. It is often treated through psychotherapy and medication (Grohol 2018).

Generally speaking, there is an expectation within the military “that we can send people off to a war zone and have them see and do the things that they [have] seen and done, and that it [is] not going to impact them….and if it does…they are are deficient in some ways…they were [not] strong enough” (Mirfendereski 2018). This expectation is unrealistic, and the statistics about how common PTSD is among returning soldiers illustrate that fact.

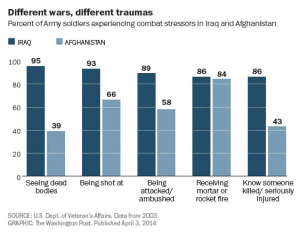

It is estimated that 11 percent of veterans from the Afghanistan War and 20 percent of veterans from the Iraq War have PTSD. More veterans from Iraq have PTSD because they were exposed to more combat than those who served in Afghanistan (Badger 2014). The chart below compares the percentage of Army soldiers from Iraq and Afghanistan that report experiencing certain traumas during their deployments. In every case, the Iraq bar is higher than the Afghanistan bar.

There is often still a stigma among military personnel that seeking help for mental health issues is a sign of weakness, which prevents some soldiers from getting the care they need. Others do not trust that the care will work, or do not want to have to jump through bureaucratic hoops to get the care they need. In some cases, soldiers decide not to get care because they know they will be deployed again and they want to ‘keep their edge’ (Ross 2011).

While the army has been trying to destigmatize mental health care, many soldiers still feel punished when they seek out care. Specialist Ryan Eddy was diagnosed with PTSD, and soon after his M-4 rifle was taken away for 90 days. He felt punished for seeking help and said, “now it seems like they think that I’m failing the rest of the squad and the rest of the platoon because I can’t use my weapon” (Jenkins 2002).

Suicide

Suicide has been a major concern at JBLM during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2002-11, more than 50 people stationed at the base committed suicide (Jenkins 2011). Overall, the Army’s suicide rate is higher than the civilian rate. Some soldiers may commit suicide because because of what they experienced while deployed, or because they do not see a way out of being redeployed, but often the trauma from deployment just adds more stress into their lives. Generally speaking, “at 24 years of age, a soldier, on average, has moved from home, family and friends and has resided in two other states; has traveled the world (deployed); been promoted four times; bought a car and wrecked it; married and had children; has had relationship and financial problems; seen death; is responsible for dozens of soldiers; maintains millions of dollars worth of equipment; and gets paid less than $40,000 a year” (Murphy 2011).

In 2011, Specialist Derrick Kirkland committed suicide after his second deployment to Iraq. He had attempted suicide twice before and was sent back from deployment so he could get care. He was released from Madigan after two days, because they considered him a ‘low-moderate risk.’ Within a week, he had died (Shapiro 2011). Jonathan Gilbert also killed himself in 2011, after facing his second deployment. The Army considered his death a “suspicious death,” not a suicide (Ross 2011). Staff Sergeant Jared Hagemann committed suicide while facing his ninth deployment. He wanted to leave the Army, but was pressured to stay in. He believed that after “the things he had seen and done, no God would have forgiven him” (Ross 2011). A soldier stationed at JBLM, whose name was not released, committed suicide in 2015 by walking on some train tracks in DuPont (Ashton 2015).

At least one soldier stationed at JBLM has committed “suicide-by-cop.” Specialist Brandon Barrett, after coming back from Afghanistan, went Absent Without Leave (AWOL) and later turned up in Salt Lake City in his combat gear with a rifle. He walked out of a parking garage and someone called 911. The police came, and he shot at the officer’s leg. In response, they shot and killed him (Jenkins 2011). The police had assumed that Barrett was about to go on a shooting spree, but his brother believes it was suicide-by-cop because “he wasn’t shooting in the way that I know he was trained to shoot. So I think it was basically, I’m going to shoot at them first and then they’re going to return fire. Suicide by cop is my opinion” (Jenkins 2011).

Madigan Army Medical Center

In 2007, a screening team at Madigan Army Medical Center was responsible for “revers[ing] more than 40 percent of the post-traumatic stress disorder diagnoses of patients under consideration for medical retirement since 2007” (Bernton 2012). The screening team was “encouraged to consider the cost of care” because caring for everyone with PTSD would be too expensive and could cause both the Army and the Department of Veterans Affairs to go broke (U.S. Senate Session 2012). “Each diagnosis is a[n] acknowledgement that psychiatric problems are a huge diagnosis of this war. If they change the diagnosis, they can dismiss you at a substantially decreased rate” (U.S. Senate Session).

More than 300 diagnoses were either reversed or changed so that the patient received less care than they should have. Some of the patients affected had been receiving care for their PTSD for a while before their diagnosis was overturned. It is important that soldiers are able to get proper diagnoses because that allows them to gain access to care, as well as military benefits such as military retirement. Military retirement allows soldiers access to health insurance and pensions. A PTSD diagnosis with medical retirement can cost taxpayers around $1.5 million over the lifetime of the soldier (Bernton 2012).

There have also been allegations that doctors at Madigan Hospital dismissed requests from National Guard members who went to the hospital seeking medical care after returning from Iraq. Many of them “were sent home and were told by officials at Madigan and the base’s Soldier Readiness Center to use Tricare or the Veterans Affairs health system because the base needed to focus on the active-duty soldiers…who were returning” home (McCloskey 2010).

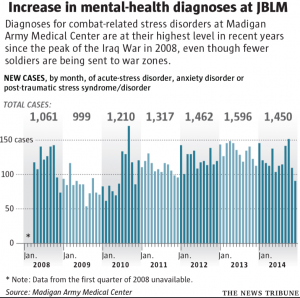

Since coming to light, the team responsible for the reversed diagnoses has been fired and the Army has provided new screenings to those affected. Many soldiers have regained access to the care they need (Bernton 2012). The graph below shows how many PSTD and anxiety cases Madigan has diagnosed every month from early 2008 to 2014.

However, some soldiers have still had issues with receiving care at Madigan. Many soldiers with service-related behavioral issues struggle with getting the care they need because their commanders viewed their behavior as flaws in their personality. Commanders tend to punish those soldiers, instead of taking the time to understand why they behaved the way they did. To prevent this “army soldiers who are involuntarily separated from active duty must first receive a separation health assessment to determine whether their medical conditions played a role in the alleged misconduct. But the Army’s longstanding medical review process and policies to protect those sick soldiers are often not effective…because commanders have the power to overrule the medical experts” (Mirfendereski 2018). If a commander believes that the soldier’s behavioral issues are deliberate, instead of related to their mental health, the soldier can receive an other-than-honorable discharge and lose their healthcare.

This happened to Sergeant Kord Ball. He had both PTSD and anxiety, and has attempted suicide multiple times. He also has behavioral issues related to his mental health, which sometimes cause him to act out. Even though his doctors at Madigan advocated for him not to be discharged for his actions, his commander thought he was acting deliberately. He was given an other-than-honorable discharge, and he lost his access to care. The army “treated him as a bad soldier instead of a sick soldier” (Mirfendereski 2018).

Military Families and Healthcare

Some military families have had trouble getting the healthcare their children need at JBLM. The Carriggs, a family with special-needs children, moved from another base to JBLM. When they moved, they were told that their children would be provided with the medical care they needed. Their son, Nickolas, had autism and mastocytosis, a condition where he can suddenly go into anaphylactic shock. Their daughter Melanie was deaf and had Down Syndrome. Upon arrival however, the family was unable to receive access to the services they were promised. In fact, the doctor Nickolas was sent to stripped him of his diagnoses of autism and mastocytosis and of the ability to access in-school therapy, which he had had access to at the last base. Melanie was only allowed to receive 1 of 2 cochlear ear implants because the hospital could only “spend the $60,000 on a typical child – not a child like Melanie” (Cahn).

The Carriggs had to resort to taking care of their children the best they could at home. Later, when Melanie was old enough to go to school and no one knew sign language, the family was allowed to move. They were able to go to a doctor who restored Nickolas’ diagnoses and Melanie was able to get her second cochlear implant. This problem is widespread on multiple bases (Cahn).

Social Crisis

Incidents of Crime

Around JBLM, there has been a number of high-profile crimes committed by soldiers. Many of these crimes were committed after soldiers came back from their deployments. In many instances, when friends and family members are interviewed afterwards, they claim that their child had changed after being deployed and that they would have never done what they did if they had not been deployed.

Several bank robberies have occurred near the base. One notable robbery was in 2006, when two Canadian civilians and several U.S. Army Rangers robbed a Bank of America. The robbery was described as being “executed with military precision” (McClary 2009). Luke Sommer, the leader of the heist told everyone who participated that he planned “to use money from bank robberies to start a outlaw motorcycle gang in Kelowna and challenge the Hell’s Angels for control of drug trafficking and other lucrative criminal enterprises in British Columbia” (McClary 2009).

Sommer later stated that his motives for the robbery were actually much different. He had been deployed once, and he was about to be redeployed in a month. The robbery was sloppy, and Sommer claims that was on purpose “so he could get caught and use the resulting notoriety to expose war crimes by U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. Aware of the news coverage Rangers-turned-robbers would generate…obvious evidence was purposely left behind to ensure they would be arrested” (Bowermaster 2007). He felt that if he had flat-out refused to deploy, it would not have meant very much because of his rank within the military. Ben Blum’s book Ranger Games details his cousin’s participation in the robbery (Blum 2017).

Alfred Sanchez, a Ranger at JBLM, stabbed someone outside of Charlie’s Bar and Grill in Olympia. Both he and his buddy, John Melville, also stole from the establishment (Pawloski 2009).

JBLM soldiers have also committed crimes outside of the immediate area. Robert Quinones took three people hostage in 2010 at a hospital in Fort Stewart, Georgia demanding mental health treatment, after being deployed to Iraq and medically discharged from JBLM (McCloskey 2010).

Benjamin Colton Barnes, who was deployed to Iraq, killed a park ranger at Mount Rainier National Park in 2012. He had been discharged from the Army in 2009 for illegally transporting weapons and for getting a D.U.I. His girlfriend left him soon after and he felt like everyone was against him (Welch et al 2012). Barnes was also involved in a shooting in Skyway, prior to fleeing to Mount Rainier. He was found dead in a river in the park a couple days later (Welch et al 2012).

Violence Against Women and Children

Violence against women and children has become more common on and off base. There have been a number of cases of soldiers murdering their girlfriends, wives, and children. Domestic abuse is generally prevalent in the military and tends to increase “right before deployment and after they come back from deployment” (Bernton 2005).

Several incidents of soldiers murdering their wives upon returning from deployment have occurred. Sheldon Plummer, after his third deployment in Iraq, murdered his wife and put her body in a storage crate. He was sentenced to 14 years in prison (Ross 2011). Sergeant James Pitts drowned his wife in a bathtub, after being back for three months (Kitsap Sun 2005). Sergeant Matthew Denni, who was in the reserves shot and killed his wife (Bernton 2005). Brandon Bare stabbed his wife 71 times after coming back from Iraq; he was part of a Stryker Brigade (Associated Press 2006). Lieutenant Colonel Robert Underwood, who had been deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq multiple times, hired a hitman to kill both his estranged wife and his boss. He also had pornographic images of his daughter and children from when he deployed (KOMO-TV 2012).

In another incident, after speeding down I-5, twice-deployed combat surgeon David Stewart and his wife were pulled over by state troopers. He and his wife were both on “Bath Salts” when they were pulled over. He shot his wife and himself in front of the state troopers. Stewart’s son was later found dead in their apartment. Bath Salts are known to alter behavior, and they have a chemical makeup similar to meth. They were banned in Washington after this incident (Clarridge 2011).

Rape has also been a concern around base. In one incident, David Vigil raped a woman and took explicit pictures of her (Dickstein 2018). In another incident, Anthony Perez, a linguist at JBLM, was caught raping a child (Esteban 2015). Several other incidents have occurred that are likely isolated but concerning nonetheless. In one, Sergeant Sterling Terrance Hospedales was caught ‘pimping’ two underage girls. He kept the money they earned and were aware that they were both under age (Seattle Times Staff 2009). In another, two teenage girls were found in the barracks at JBLM, one dead and one unconscious (Perry 2009). There was no signs of trauma, but the autopsy showed that the girl had taken a variety of prescription drugs (Sullivan 2009). Sergeant Duane Michael Rader poured lighter fluid on his wife’s legs and lit them on fire. It is not known if he was ever deployed (Associated Press 2011).

Violence against children and families has also been an issue. An unidentified solider from Spanaway shot both his wife and two children before killing himself in Spanaway in 2018 (Glenn 2018). In a 2010 incident, soldier Joshua Tabor waterboarded his daughter because she could not recite her ABCs. He chose to waterboard her because she was afraid of water. He was later arrested walking around his neighborhood in a Kevlar helmet, threatening to break windows (Staff 2010).

Traffic

A less troubling but nevetheless disruptive aspect of the base is its heavy effect on traffic in the area. The area around JBLM “has grown nearly by 160,000 [people] since the US first went to war in Afghanistan” and on base the number of family members, contractors and civilian employees has grown by 40,000. The roads around the base, including Interstate-5 (I-5), have not been updated since being built in the 1960s. It is very difficult to get around traffic jams near the base, because the base is on both sides of the freeway, and so creates a chokepoint (Smith 2011).

In response, Mounts Road (at Exit 116) has been opened up during the mornings and the truck scales have been adjusted, so trucks can avoid the freeway. JBLM has also staggered troop workouts, so they can arrive at base at different times. An auxiliary lane was also added between the exits of Thorne Lane and Berkeley Street (Sullivan 2014). More recently, a double turn lane has been added to the Berkeley Street overpass and an additional southbound lane has been added. Sidewalks have also been improved on the overpass (I-5 Exit Guide).

Conclusion

Clearly, there are persistent social and health crises around JBLM. However, there have been attempts to solve these problems. To address domestic violence, the Family Advocacy Program and the Airmen and Family Readiness Center have partnered together to start educating soldiers on the topic through events and displays throughout the base (Levering 2010). The Army has started encouraging soldiers to seek mental health care. One way they have encouraged this is to embed mental health doctors within units. These doctors have a clear idea of what the unit has experienced, and can build relationships with the soldiers, so they feel more comfortable receiving care (Bernton & Ashton 2015). To address suicide, Army has started a suicide prevention program called Shoulder to Shoulder to break down the stigma around mental health in the army. The program interviews soldiers who have attempted suicide and shows these interviews to soldiers so they can see that others have struggled with the same issues (Jenkins 2011).

There are also civilian and veterans groups who are advocating on behalf of veterans, so they can access medical care. The Right to Heal coalition is one of those groups. They have been holding the government accountable for caring for veterans from the Iraq War, and they supports Iraq’s struggle to rebuild itself (The Right to Heal). Another example is Operation Recovery, a campaign by Iraq Veterans Against the War. Its goal is to stop the Army from deploying troops who have PTSD, Military Sexual Trauma, or Traumatic Brain Injury. They also oppose the ability of commanders to overrule medical experts’ advice, which is what happened to Sergeant Ball (Iraq Veterans Against the War).

Even though it may take awhile for the Army to fix these problems, it is encouraging that there are people working to solve these issues. However, it is possible that these problems will become even worse if the U.S. is involved in another large-scale war, because the VA may not have the resources to take care of everyone who comes back needing mental care. That is what happened at Madigan Hospital during the Iraq War, and that could happen again. Instead of rushing into another war, we should prioritize caring for those who have already served and continue to feel the effects of their service daily.

Sources

Ashton, A. (2015, October 22). Death of JBLM soldier hit by train investigated as suicide. News Tribune.

Bernton, H. (2005, July 15). Soldier charged in wife’s death. Seattle Times.

Bernton, H. (2012, March 21). Madigan Army Medical Center screening team reversed 40 percent of PTSD diagnoses. McClatchy DC.

Bernton, H. (2012, March 20). 40% of PTSD diagnoses at Madigan were reversed. Seattle Times.

Bernton, H., & Ashton, A. (2015, April 11). As PTSD cases surge, Army overhauling mental health services. Seattle Times.

Bowermaster, D. (2007, February 8). The Army Ranger who robbed a bank. Seattle Times.

Cahn, D. (n.d.). “We are just tired of this fight:” Special-needs families say military is still failing them. Stars and Stripes.

Clarridge, C. (2011, June 13). Fort Lewis soldier who killed wife, self had taken synthetic ‘bath salts’ drug. Seattle Times.

Glenn, S. (2018, March 13). Deputies: Man kills wife, 2 children in their beds, then shoots himself. Stars and Stripes.

Jenkins, A. (2011, August 4). Family Faults Army In Case Of AWOL Soldier Killed By Police. National Public Radio.

Jenkins, A. (n.d.). 50 Joint Base Lewis-McChord Suicides Since 2002.Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Kitsap Sun. (2005, April 24). Jurors convict sergeant who drowned wife in bathtub. Kitsap Sun.

KOMO-TV. (2012, March 14). Charges: JBLM officer claimed to hire hit man to kill wife. Seattle Pi.

Lewis-McChord, J. B. (2018, December 4). I-5 CONSTRUCTION PROJECT IMPACT. Twitter.

McClary, D. (2009, October 31). U.S. Army Rangers from Fort Lewis rob the Bank of America branch in South Tacoma on August 7, 2006. History Link.

McCloskey, M. (2010, September 17). What’s happening at Joint Base Lewis-McChord? Stars and Stripes.

Rempfer, K. (2020, May 13). Murdered veteran ‘fingered’ two JBLM soldiers now charged in his death for a ‘drug incident’ last year, affidavit says. Army Times.

Ross, W. (2011, September 9). PTSD at Joint Base Lewis-McChord: Suicides, Murders, and Soldiers Waterboarding Their Kids. Daily Beast.