Donald Evans

Whatever the future holds, do not forget who you are. Teach your children, teach your children’s children, and then teach their children also. Teach them the pride of a great people … A time will come again when they will celebrate together with joy. When that happens my spirit will be there with you. – Chief Leschi (Nisqually)

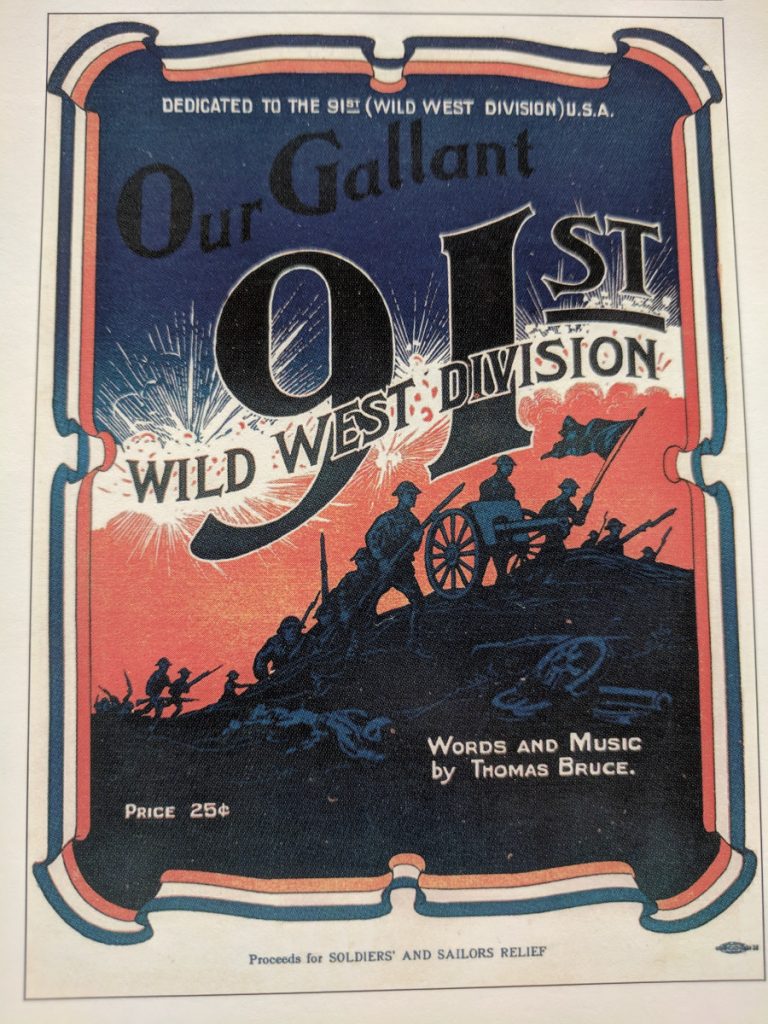

In March 1916 General John Pershing was tasked with the manhunt for Mexican revolutionary Francisco “Pancho” Villa who had launched a raid into Columbus, New Mexico. Books such as Hudson Maxim’s Defenseless America and films such as The Battle Cry of Peace, popularized military preparedness and, “…expressed a legitimate concern for America’s ability to defend herself if she were pulled into World War I” (Lewis Army Museum 2014). To prepare for possible war, forts in the Pacific Northwest started to be built, including Camp Lewis (later Fort Lewis) just south of Tacoma, Washington. From World War I to the present day, the base has had some connection with every war where the U.S. has been involved, from the 91st Division in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive of World War I, to the Stryker brigades in Iraq and Afghanistan.

World War I

There is no finer Army post site anywhere in the U.S. In this area there is every physical condition desirable for Army training and maneuvers. – Major General Arthur Murray

In 1916 the Pierce County Military Base Committee formed in response to Congress passing a law that allowed the Secretary of War to accept land that was donated for construction of military installations. The committee was hoping to capitalize on the “economic boom” that it felt would follow the construction of a military base (Dunkelberger 2017). The committee was successful, and Camp Lewis was built. On April 6, 1917, the U.S. formally declared war on Germany and the construction of Camp Lewis was expedited. Construction of Camp Lewis occurred simultaneously as soldiers trained.

Camp Lewis was a scene of building construction and road scraping, amidst the tumult of recruits learning close-order drill and machine gun training; the sound of hammers and of 1903 Springfield’s being fired on a 200-point rifle range; the laying of a spur line for support trains; and of horse-drawn field artillery training in columns (Lewis Army Museum 2014).

The Wild West Division

Camp Lewis built the first Army barracks for draftee training, and the first unit to be created was the 91st Division. Comprised mostly of men from the western states, they went with a unit logo represented by a fir tree and nicknamed the “Wild West Division.” In preparation for going to Europe, the troops were trained in close drills, military traditions, bayonet thrusts, and hand-to-hand combat. To prepare for reality on the battlefields of Europe, they had mock battles in trenches and experienced gas attacks in special rooms (D.C.D. 2008).

Of the original 70,000 acres given for Camp Lewis, about 3,300 acres were Nisqually Indian allotments, comprising about two-thirds of the Nisqually Reservation (see Nisqually and Fort Lewis). Initially, training and firing ranges were located near the barracks area. Eventually troops started to train on the Nisqually lands, causing damage to farmland. In the winter of 1917 the U.S. Army moved onto Nisqually lands and ordered tribal members from their homes without any warning (Nisqually Indian Tribe, n.d.). As Brigadier General James A. Irons (Camp Lewis acting commander) stated that Camp Lewis needed the Nisqually tribal lands for an artillery range, crucial in the proper training for the war in Europe (D.C.D. 2008).

Interwar Years (1919-1941)

Camp Lewis is the most valuable military possession in the United States…large enough to train infantry movements and provide room for the firing of the heaviest guns. – Major General U. G. McAlexander

As World War I was coming to an end, the 13th Division was at Camp Lewis training and preparing to go to Europe. The war ended November 11, 1918 as the 13th was training for trench warfare. Camp Lewis shifted its role to preparing troops to return to civilian life rather than training for combat (a pattern after every war) by Camp Lewis being converted to a separation center. The 13th Division was nearly demobilized by February 1919, except for the 13th Field Artillery Brigade which was deployed to Seattle to assist in suppressing the Seattle General Strike. Later, demobilization resumed, and the soldiers of the 13th Field Artillery Brigade were soon discharged to civilian life (Laurie & Cole 1997, 262).

With the high financial costs of World War I, Congress chose to slash the military budget and return to a prewar isolationist stance. Camp Lewis fell into a neglected state. As the old wooden structures were being torn down, people in the surrounding area became concerned that the camp was being abandoned. Local groups led by the Rotary Club and the Tacoma News and Tribune had always expected that a division of troops be stationed at the camp. They thought that the agreement with the federal government called for a whole division, while the agreement actually called for the post to remain in the hands of the government so long as it was used for training purposes (Lewis Army Museum 2014b). In 1921 the Army moved the 3rd Division headquarters to Camp Lewis in order to please these local groups.

Training at Camp Lewis, Washington, 1936 (Credit: US National Archives).

From Camp to Fort

On September 30, 1927 the War Department issued General Order No. 15, renaming Camp Lewis as Fort Lewis, which made it a permanent post (D.C.D. 2008). At the same time, Pierce County was beginning construction on a municipal airport (Tacoma Field) near the newly named Fort Lewis. The U.S. government purchased the airfield in 1938 and renamed it McChord Field, in honor of Colonel William C. McChord, who had been killed in a 1937 accident in Virginia (McChord Air Museum n.d.). As another World War was erupting in Europe and Asia, the U.S. Army Air Force set off to strengthen the airfield by constructing barracks and giant hangars with workers employed by the Depression-era Works Progress Administration (D. C. D. 2011). (McChord Field become McChord Air Force Base later in 1947 with the division of the Army and Air Force branches).

World War II

I could think of no better assignment at a time when much of the world was at war. – Lt. Col. Dwight Eisenhower

Even before the U.S. entered World War II, Fort Lewis showcased a major air-power event on its training range. With Japanese bombers over China and Korea, and Spanish cities being leveled by German bombers in the Spanish civil war, there was popular interest in the demonstration:

Fifteen B-18 bombers and twenty-one A-17-A fighters gave a civilian and military audience of 3,000 a vivid demonstration of the destructive capabilities of modern airpower. Using live ordnance, the warplanes dropped over 400 bombs on a mock city, completely destroying it. No cameras were allowed at the demonstration (Lewis Army Museum 2014a).

Northward Base Expansion

Fort Lewis boasted 5,000 men in garrison by May 1938. Infantry training and field maneuvers became the norm on post. With an increased number of troops an additional 455 permanent and temporary structures were constructed. By July 1940 the garrison was at 7,000 troops and after September that number would explode due to the one-year Selective Service Act being implemented. By Christmas the garrison saw 26,000 troops mixed between draftees, regulars, and guardsmen. Space was becoming limited.

The 41st Infantry Division arrived at Fort Lewis in Fall 1940. Consisting of over 12,000 men, most from the Washington National Guard, they had to be housed in 3,000 “winterized” tents at the adjacent Camp Murray, nicknamed “Swamp Murray” by the troops. About 11,000 more troops arrived in March 1941. This increase made it necessary to construct an auxiliary training and troop center on the northern part of Fort Lewis called Third Division Prairie, which covered a two-mile by one-and-a-half-mile area near DuPont. The $4 million building campaign was designed to house an entire division (Shopify n.d.). Now Fort Lewis was bolstered with 37,000 troops, who were in maneuvers by spring on the Nisqually Plain training area:

…the combination of civilian construction crews and Army work details was making real progress on the raising of barracks and training ranges on North Fort Lewis. In April, the initial 2,000-acre North Fort complex was unadorned and unpainted, but it was fully ready for use by August 1941 (Lewis Army Museum 2014e).

By October 1941, Fort Lewis was still conducting war games, with the Puget Sound seeing amphibious operations by using motorized wooden whaleboats as landing craft to resemble beach landings. This hectic training would continue for these 37,000 men.

Training was taken to a new level when, on December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Through local radio stations, a broadcast was sent that all personnel stationed at Fort Lewis, Camp Murray, and McChord Field were to report immediately to their units for further orders. Unit commanders were contacted after the attack and the 41st Infantry Division was ordered to establish a tight perimeter security on the three bases. The 3rd Infantry Division, clad in full field gear, was sent to the Fort’s training ranges to erect anti-aircraft batteries, and the 115th Cavalry Regiment was trucked to the area’s beaches for shore patrol and coast-watching duty (D.C.D. 2008a).

Additional Base Expansion

In early 1942, as vehicle maintenance needs increased the motor-repair base located in Northeast Fort Lewis and Fourth Division Prairie needed expanding. New shops and housing were built and were responsible for rebuilding vehicles from the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, due to tough conditions that would quickly wear out even the sturdiest of military trucks. Again, the need to expand rose due to a heavy influx of vehicles which led to a facility upgrade that become the Mount Rainier Ordnance Depot in December 1942. The overhauled shops had factory lines to disassemble vehicles and replace worn out systems. Women would hold about 40 percent of these jobs and a vocational school was established at the Clover Park High School to teach mechanics. The depot had 2,300 employees and 190 buildings (D. C. D. 2008.-a).

Before World War II had even ended, Fort Lewis had trained and sent off many known and highly decorated units, among them the 3rd, 33rd, 40th, 41st, 44th, and 96th Infantry Divisions. To accommodate the training of all these units the base required an additional expansion. The Rainier Training Area was created in March 1943 on about 18,000 acres on the south side of the Nisqually River. A greater need for medics and engineers was needed and Fort Lewis in July of 1944 was re-designated as an Army Service Forces Training Center, which became the largest in the nation (World War II, 1939-1949 2014).

Women’s Army Corps

Base expansion included the arrival of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC’s) who received training in administrative functions and medical roles to perform during the war. A popular slogan for the WAC was “free a man to fight.” Other duties the women performed at Fort Lewis included guard duty and motor pool dispatching. There was a nursing shortage in 1944 and to compensate, WACs started working in military hospitals as trained medical technicians and later entered other technical occupations such as optometry and pharmacology (D.C.D. 2008a).

World War II Ends

In 1945 as World War II ended, Fort Lewis shifted from training and sending troops to being established as a separation center to discharge returning soldiers. Northeast Fort Lewis was used as the separation center and oversaw the discharge of 200,000 servicemen between November 1945 and February 1946. Fort Lewis would not stay quiet for long as a new “type” of war with a formidable foe was lurking just around the corner.

Cold War Era (1947 – 1991)

Korean War

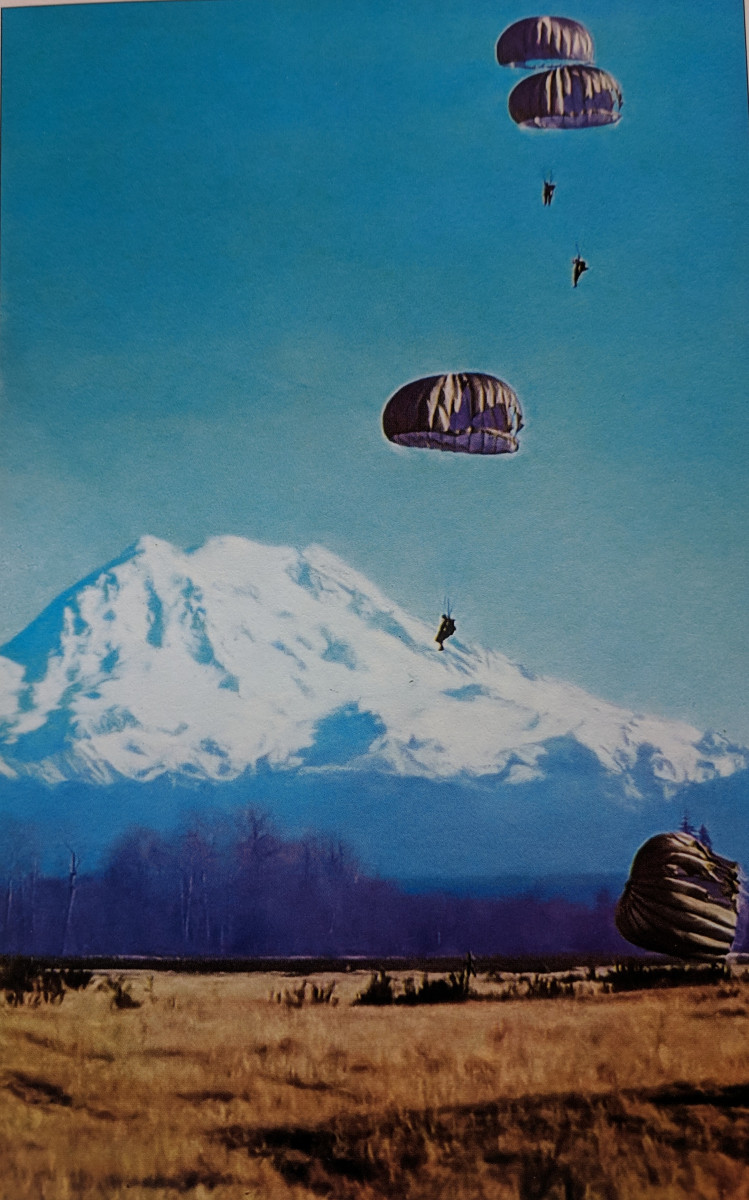

The 2nd Infantry Division, also known as the Indianhead Division (as shown in the division patch), was posted and trained at Fort Lewis until its deployment for a new war in Korea in the summer of 1950. The 2nd was well trained for Korea as it performed four large-scale maneuvers before deployment: an amphibious assault in 1946 at Aliso Canyon, California; a month-long combat operation at the Yakima Firing Center in 1947; “Operation Yukon” in 1948 when troops were indoctrinated in airborne training in Alaska; and the 1929 “Operation Miki” a mock large-scale invasion of the Hawaiian island of Oahu (Lewis Army Museum 2014.-c).

With all this training the 2nd I.D. was the first to be sent to Korea in 1950. North Fort Lewis was where the 2nd was normally housed and so while it was in Korea it became an overseas replacement center, where it processed and shipped out soldiers bound for Japan, Korea, Okinawa, and Alaska. Enlisted reservists were recalled to active duty, due to the escalating of the Korean War, and they poured into Fort Lewis. The reception personnel worked around the clock to receive, process, and assign 4,594 soldiers in a week and a day.

The reservists received refresher training and courses with emphasis on medical, antiaircraft, infantry, and field artillery. Even Canadian troops would be sent to North Fort Lewis to train for the war in Korea. This might have been the first large armed group of a foreign nation ever to train in the United States, due to Canada having no base of its own large enough to amass such a force. Fort Lewis was still suffering from a housing shortage with the influx of draftees and reservists. Construction began for two regimental areas situated near many of the post’s combat ranges (Lewis Army Museum 2014.-c).

Changing of the Guard

At the end of the Korean War, reception and replacement duties were no longer needed and Fort Lewis went quiet again. With two new regimental barracks with permanent concrete buildings, the 2nd Infantry Division returned to Fort Lewis, but only for a short stay. It was soon replaced by the 4th Infantry Division (Ivy Division). In the years just prior to the war in Vietnam, Fort Lewis became home to the U.S. Army’s first large-scale experiments in counterinsurgency warfare. Fort Lewis-based units conducted counterinsurgency focused exercises, “to develop and validate the nation’s embryonic doctrine for fighting the Cold War’s numerous ‘wars of liberation’” (E. W. Flint n.d.-a).

In 1956 the (“Famous Fourth”) 4th Infantry Division called the Fort home and would end up training several cycles of recruits. By 1963, conventional elements of the 4th Division were training to fight an unconventional war. They trained in different exercises from Fort Lewis to deep in the wilds of the Olympic Peninsula. Training included the joint element of the Air Force.

The final exercises were specifically designed to prepare the 4th Division for deployment to South Vietnam. The exercises were called Helping Hand I and II and Frontier Post I and II and had a decidedly Southeast Asian jungle emphasis. The training even incorporated specific cultural elements such as Vietnamese social organization in training villages and mock Buddhist temples. The 4th Infantry Division departed via the Port of Tacoma, “with crowds cheering and bands playing” to Vietnam with their new training in counterinsurgency for four years in the jungles (E. W. Flint 2017b). Once again, Fort Lewis became an Army Training and Replacement Center, to train soldiers and to send and receive them from the Pacific.

Training for the Vietnam War

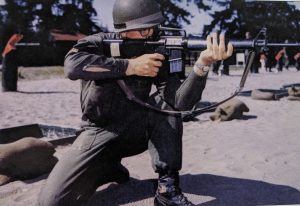

In 1968, the U.S. Army Training Center-Infantry-Fort Lewis added a ninth week to the basic training. While trained in basic combat, the ninth week added an advanced infantry training with a focus on the rigors of jungle counterinsurgency warfare to specifically cover the unique requirements of what to expect in Vietnam.

To simulate what to expect in Vietnam, two villages were constructed, which included realistic elements such as a tunnel system and live role-players to portray enemy, friendly and neutral forces. A Vietnamese-style firebase was also constructed to prepare for fights from remote fortified locations, like the ones to be found in Vietnam (Flint 2017a). (See Vietnam at Fort Lewis).

|

|

In the Vietnam Era, Fort Lewis saw the transition from the main M-14 7.62 semiautomatic rifle to the M-16 rifle. Troops would learn basic marksmanship and then qualify with the M-14 first then later with the M-16. Troops would qualify under either expert, sharpshooter, or marksman. Training also included live-fire exercises. Fort Lewis was unique in that it was one of only two Army Asia-Pacific personnel processing centers:

It was not uncommon for a soldier to complete both Basic and Advanced Infantry training at Fort Lewis, be processed for Vietnam through the Personnel Center, fly to South Vietnam from nearby McChord Air Force Base, serve a one-year combat tour, return to McChord and be processed out of the Army without ever having been to another stateside Army post (Flint 2017c).

Reforger

Participating in Reforger, a 1968 program associated with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Fort Lewis accepted certain units which specifically and urgently would be deployed to Europe in the case the Soviet Union started an attack on West Germany (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2018). These units, while staged in the U.S, would have their equipment and weapons strategically stored in Europe. In all there were about 6,000 Reforger troops at Fort Lewis such as the 212th Artillery Group and the 3rd Armor Calvary (Shopify n.d.).

Ending the Cold War

“Old Reliables”

As the war in Vietnam was coming to an end, in 1972 both the training and personnel centers were ordered closed at Fort Lewis. Once again, the Army would activate a major combat unit when the future of Fort Lewis appeared in doubt. The 9th Infantry Division, also known as “Old Reliables,” moved in as the first All-Volunteer-Force Army unit and remained there until deactivation in 1991. With a shift to an all-volunteer army, the 9th saw some of the first recruitment campaigns in order to bring recognition to its new home at Fort Lewis (Archambault 2016, 46). The 9th Infantry Division would go on to be trained in “fast attack and mobile infantry movement,” giving Fort Lewis more relevance in the Pacific (D.C.D. 2008a).

Weapons Testing and Controversy

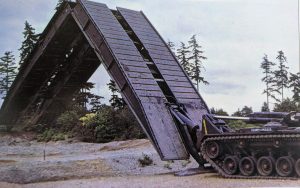

In the 1980s the 9th Infantry Division as part of its new “attack and mobility” strategy became a testing unit for some familiar military hardware such as the High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle (HMMWV) which replaced the iconic “Willie” Jeep, to more obscure vehicles such as the experimental Fast Attack Vehicle (FAV) which saw limited use with Special Forces units. This became known as the High Technology Test Bed (HTTB).

“The Test Bed was to explore all types of equipment, military and civilian, foreign and domestic, which would be suitable for the new unit. They were to acquire this equipment in the most expeditious way possible, short cutting the normal 10-15 year procurement cycle”(Lewis Army Museum 2014.-d) Along with the new testing, traditional testing still took place at the ranges, such as small arms and 155-mm howitzer artillery.

Training would not be complete without night training, which caused controversy over whether the Army used the radioactive Davy Crockett spotting rounds on the Fort Lewis ranges.

The M28 Davy Crockett was an early battlefield nuclear weapon system used in the US until the early 1970s. According to the International Coalition to Ban Depleted Uranium Weapons, its primary purpose was “to prevent the advance of oncoming enemy troops, by the power of the explosion, and the deterrent effect of irradiating an area.” The M101 was not the “main round,” but the spotting round “fired from a small 20-mm rifle attached to the larger barrel.” The main round was the M388, which could carry either “conventional explosives or the W54 nuclear warhead” (Storms 2012).

The issue of these rounds being used at Fort Lewis was they contained Depleted Uranium (DU) which is a radioactive toxic heavy metal, which is ideal for penetrating heavy armor. Tests showed the presence of radon, a radioactive result of decaying processes of DU (Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2015).

1990s

Only a few Fort Lewis units participated in the 1991 Gulf War (see Iraq). At the start of the decade, the Department of Defense terminated the 9th Infantry Division and it was gone by February 1991. The start of a new type of weapons system, named the Stryker armored vehicle, meant that testing would begin and like the 9th Division in the 1980s:

Fort Lewis was once again at the forefront of development for a medium force — soldiers that could get to the ‑ fight fast with enough ‑ firepower and protection to sustain a ‑ fight. this concept began here in 1999 when Army Chief of State Eric Shinseki designated the 3rd Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division to be the first Stryker test concept, only known then as a prototype unit. (Shopify n.d.).

A Changing World

After September 11, 2001, Fort Lewis units took on significant roles in the new “Global War on Terror.” Stryker Brigades, equipped with the Interim Armored Vehicle (IAV), or more commonly known as Stryker armored vehicles (named for Medal of Honor recipients Private First-Class Stuart Stryker [1924-1945] and Specialist Four Robert F. Stryker [1944-1967]). The Stryker demonstrated rapid deployment and effectiveness. A Stryker and Stryker Brigade Combat Team (SBCT) simply put:

Stryker is a family of eight-wheel-drive combat vehicles, transportable in a C-130 aircraft, built for the US Army by General Dynamics Land Systems…Stryker is based on the GDLS Canada LAV III 8×8 light armored vehicle, in service since early 2001…The Stryker brigade combat team (SBCT) combines the capacity for rapid deployment with survivability and tactical mobility. The Stryker vehicle enables the team to maneuver in close and urban terrain, provide protection in open terrain and transport infantry quickly to critical battlefield positions. The eight-wheeled Stryker is the first new military vehicle to enter service into the United States Army since the Abrams tank in the 1980s. The contract for the US Army’s interim armored vehicle (IAV) was awarded in November 2000. The vehicles form the basis of six brigade combat teams. The contract requirement covers the supply of 2,131 vehicles (Stryker Armoured Combat Vehicle Family n.d.).

U.S. Army Combined Arms Live Fire Exercise at Joint Base Lewis-McChord (Credit: Free Fire Zone).

Comprising of a crew of two to operate (commander and driver) and up to three (with a gunner) plus nine troops for transport. Other Fort Lewis assets were also drawn upon such as the Special Forces and Ranger units (Historylink n.d.). (See Iraq and Afghanistan at Fort Lewis).

Leschi Town

Leschi Town is the U.S. Army’s newest Military Operations in Urban Terrain (MOUT) training facility and is named for Chief Leschi of the Nisqually tribe who lived and trained his warriors in the area (Charles 2005, 38). With global combat becoming ever more urbanized, the U.S. would no longer follow the military doctrine of bypassing cities. This type of combat was reserved for units such as the Rangers and other Special Operation units. “But based on U.S. experiences in Somalia and the Balkans, and the Russian Army’s bitter campaign in Chechnya in 1994-95, strategists realized they needed to reach all combat troops, not just Special Ops” (Press n.d.).

P.R. Images

Training exercises at Leschi Town such as “Operation Tomahawk Shock” named after the 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, also known as the Tomahawks, took place at Leschi Town in 2008. With lasers simulating live fire, one of the many purposes for this training was to see what mistakes the soldiers made so the mistakes do not repeat in real-world scenarios. An example during the training, which used Arabic-speaking people to simulate Iraqi civilians, a “detainee” escaped. As the detainee ran a soldier “shot” him in the back right above his bound hands. This particular scenario also simulated a “media crew” arriving to film. As Stryker battalion commander Lt. Col. Charles Hodges said of the detainee being shot during the exercises, “You can do a great tactical operation, but if the media sees someone shot and others arrested, when you’re supposed to be there saving the water facility, then you’ve lost strategically.” The soldier who shot the detainee was “admonished by his superiors” during post-exercise discussions (Fontaine 2008, B1).

National Guard Officer Candidates from 15 different states performed urban operations training at Leschi [Town], a mock town, on Joint Base Lewis-McChord during OCS phase 3. The exercise helps the candidates maneuver and gather information in an urban environment, it also gives them the training to engage enemies in that environment (Credit: Washington National Guard).

Training in V.R.

More recently a Virtual Reality (VR) aspect to Leschi Town has also been incorporated into the training. Through MetaVR, the virtual Leschi Town can be used for both simulated Close Air Support (CAS) missions and pre-mission rehearsals. After completing the pre-mission rehearsal in the simulator, the trainees then may go on to train at the physical Leschi Town. The VR program hopes to simulate urban combat and improve the soldier’s situational awareness. The VR training enables soldiers to get to know the area before they set foot into the real Leschi Town (MetaVR n.d.).

Training has changed from the early days of 1917, with the 91st Division training in mock trenches to prepare for what to expect in Europe, to the “Famous Fourth” Infantry Division and the mock Vietnamese villages and tunnels, to today’s Special Forces and regular troops in Leschi Town in real life and VR (MetaVR n.d.). But in many ways, the training has incorporated similar aspects of the cultural and physical terrain on the real-life battlefield.

Conclusion

“The U.S. Army is planning to expand its efforts to counter China by deploying a specialized task force to the Pacific capable of conducting information, electronic, cyber and missile operations against Beijing. The unit, which Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy detailed…would also be equipped to hit land- and sea-based targets with long-range precision weapons such as hypersonic missiles, possibly clearing the way for Navy vessels in the event of conflict…..The pivot includes greater Army participation in regional war games such as the ‘Defender Pacific’ series and deploying a ‘Security Force Assistance Brigade’ next year for the Indo-Pacific theater similar to ones set up and deployed to Afghanistan, he said. The Army started experimenting with the task force in 2018. The 17th Field Artillery Brigade from Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington State conducted nine major training exercises plus simulations and war games to evaluate concepts” (Capaccio 2020).

As time goes on, the types of training and weapon systems change to meet the Army’s needs as the types of battlefield change. Long gone are the days of thousands of troops amassing in trenches awaiting to go over the top into the unknown, as will one day the need for weapons systems such as the Strykers. Technology-based warfare will only be ramping up as time goes on, with advancements in sonic weapons, drone warfare, and cyberwarfare. Who knows what capacity this Pacific Northwest base might see in the future, if at all.

Sources

Banel, F. (2015, July 10). The forgotten early history of Joint Base Lewis-McChord. My Northwest.

Capaccio, Tony. (2020, January 11). Army plans specialized force to counter China. Bloomberg News.

D.C.D., Ph D. (2008, January 16). Fort Lewis, Part 1: 1917-1927. History Link.

D.C.D., Ph D. (2008a, April 18). Fort Lewis, Part 2: 1927-2010. History Link.

D.C.D., Ph D. (2011, October 25). McChord Field, McChord Air Force Base, and Joint Base Lewis-McChord: Part 1. History Link.

D.C.D.., Ph D. (2018, June 21). Fort Lewis, Part 4: 1927-2010. Nisqually Valley News.

Dunkelberger, S. (2017, February 11). How Joint Base Lewis-McChord Took Shape 100 Years Ago. Thurston Talk.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2018, December 19). Fulda Gap / Lowland corridor, Germany. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Flint, E. W. (2017a, February 23). Vietnam tours began here. JBLM Northwest Guardian.

Flint, E. W. (2017b, March 23). Fighting the Cold War. JBLM Northwest Guardian.

Flint, E. (2017c, April 20). Fort Lewis major training hub for Vietnam. JBLM Northwest Guardian.

Fontaine, S. (2008 November 4). Actors, simulation help platoon train for Iraq. The Olympian. Page B1.

Laurie, C. D., & Cole, R. H. (1997). The role of federal military forces in domestic disorders, 1877-1945. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Page 262.

Lewis Army Museum. (2014, November 28). Camp Lewis, 1917-1919.

Lewis Army Museum. (2014a, November 28) Fort Lewis – The Permanent Post is Established, 1927-1939.

Lewis Army Museum. (2014b, November 28). Interwar Doldrums, 1919-1927.

Lewis Army Museum. (2014c, November 28). Korea, 1949-1955.

Lewis Army Museum. (2014d, November 28). On the Cutting Edge.

Lewis Army Museum. (2014e, November 28). World War II, 1939-1949.

MetaVR. (n.d.). MetaVR’s Virtual Leschi Town MOUT Site used in JTAC Training at Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

McChord Air Museum. (n.d.). McChord Air Force Base History 1939-1950.

Nisqually Indian Tribe . (n.d.). Heritage. Nisqually Indian Tribe.

Nuclear Regulatory Commission. (2015, September 4). U.S. Army Installation Command, Davy Crockett Depleted Uranium. Office of the Federal Register.

Shopify. (n.d.). 100 Years Celebrating a Centennial at Joint Base Lewis-McChord 1917-2017.

Storms, N. (2012, September 20). FOIA documents show Fort Lewis used depleted uranium munitions in 1960s. Works in Progress.