Conner Lyons

Value Shifts and Activism

The United States experienced a shift in attitudes after the long and brutal World War II. Americans “went from valuing resources and landscapes primarily for their economic worth to valuing them also for their aesthetic qualities and amenities. As they became more affluent in the postwar era, people were less likely to consider resources wasted if they were not exploited for economic gain. Americans sought a better quality of life, one manifestation of which was the desire to live on the fringe of the city, where there was less congestion and pollution” (Drosendahl ______). The ideological shift centered around environmentalism, more careful consumerism, and attention to beauty rather than only function.

Kitsap County was ironically a perfect place for this kind of value shift, reflected in activism. People in Kitsap County (for the most part) love living where they do. Many even move there intentionally because of the high quality of life. “Many Kitsap County residents attributed their quality of life to the rural nature of the area and the scenic beauty of Hood Canal and the Olympic Mountains. Residents idealized this aspect of the area. Kitsap County had the second highest population density in Washington State in 1970, exceeded only by King County. Only a tiny fraction of the county’s labor force held jobs in traditional rural industries such as agriculture, forestry, and fishing. Nonetheless, some locals viewed their area as pastoral, and they valued rural and bucolic lifestyles over urban. Kitsap was, therefore, not so much rural as it was ‘pseudo-rural.'” (Drosendahl _____). One letter-writer to the Kitsap Sun called the county a “pseudo-rural Fortress Kitsap” (Dazma 2003).

In many ways Kitsap County gives people “the best of both worlds” as far as rural and urban living. Kitsap has been a hotbed for antiwar activism partly because the military presence here is so strong, but also because the area is so stunning and some people do not want their land and lifestyle ruined by military hegemony.

Antiwar Activism

Many Americans have a stereotype about who activists are and what they look like. Opponents of the Trident nuclear submarines are often portrayed as wealthy Seattle elites, but this is not the case. Opponents also included many retirees, people of limited means, and members of the general public who feared rising taxes and property values, increased strains on public services, and changes in what they perceived as the rural nature of the area” (Casserly 2004).

From this description a person can a easily reach the conclusion that antiwar activism does not only spur from a sort of “tree-hugging” frame of mind, but extends far beyond superficial liberal ideology. Many residents would rather have the military budget spent on public services such as schools and transportation, and some want to protect the land from military base environmental impacts. Some people feel that violence does not solve conflicts, and other people do not want increased taxes and development in their county. Activism cannot be defined so easily, the reasons to quesiton military weapons and bases are endless.

Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action

Probably the most impactful group of resisters in Kitsap County is the anti-nuclear weapons group Ground Zero. The Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action is located in Poulsbo, literally on the fence boundary of Bangor Trident base, the place that houses more nuclear weapons than any other base on the entire planet. Ground Zero has been doing what it can to resist Tridents through peaceful protests and other kinds of nonviolent resistance. Ground Zero does a wide variety of peace work, from advertisements on buses to physical blockades in the front of the main entrance of the Bangor Trident base.

On its website, Ground Zero stresses its close proximity to the base as part of a civic responsibility. “When citizens become aware of their role in the prospect of nuclear war, or the risk of a nuclear accident, the issue is no longer an abstraction. Our proximity to Bangor demands a deeper response” (Ground Zero). Ground Zero wants people in Kitsap County and the entire region to know that the horrific destruction that could be caused by a nuclear war is not somewhere else, it is here.

Ground Zero’s protests are intersectional and symbolic. One article on its website titled; “Time to Disarm the Patriarchy!” focusing the intersections between militarism and male domination in policymaking decisions. As part of its physical resistance to Bangor base, Ground Zero has often blocked the main entrance on Mother’s Day as a reminder that, “The Earth is our Mother. Treat her with Respect.” Another banner stated “We can all live without Trident.” Along with these actions Ground Zero has organized peace walks from Eugene, Oregon to the Bangor submarine base, focusing on remembrance of the atomic bombings in Japan. The theme of the 2018 walk was “No More War – A World Without Nuclear Weapons.” Participants “stopped in cities along the way, listening, and sharing the voices of the victims of warfare. This was the fourteenth year of the August Peace Walk” (Ground Zero). Nonviolent protests do not have to be wimpy or ineffective. But, as Ground Zero notes on its website, nonviolence focuses on “love, compassion, kindness, peaceful understanding and social justice, what we say and what we don’t say, what we do and don’t do, affects our part of the world in ways we may never know. While few of us have the power as individuals to create global peace, one by one, collectively embodying nonviolence as a way of life, each of us can help move the world a little closer in that direction” (Ground Zero).

Plowshares Activism

Another powerful antiwar campaign active in Kitsap County is the Plowshares movement. Plowshares activists have literally cut holes in the fence of the Navy base, and entered the grounds as a form of direct resistance to the nuclear weapons. The Plowshare activists were caught and arrested by security, but testified in court saying that they entered the base in an attempt to call “attention to the illegality and immorality of the existence of the Trident weapons system” (Eiger 2010). They even symbolically spilled some of their own blood on the weapons storage, causing the Navy embarrassment for the severe security breach.

For these people, religion is a major pillar in the antinuclear weapons resistance work. The Plowshares movement stated that its resistance to nuclear weapons comes from feelings that “the manufacture and deployment of Trident II missiles, weapons of mass destruction, is immoral and criminal under International Law and, therefore, under United States law. As U.S. citizens we are responsible under the Nuremberg Principles for this threat of first-strike terrorism hanging over the community of nations, rich and poor. Moreover, such planning, preparation, and deployment is a blasphemy against the Creator of life, imaged in each human being” (Dambergs 2018). In this way religion can legitimize a social justice movement, giving the movement a large audience and potentially mass appeal from people who might think of the military and nuclear weapons in terms of “blasphemy against the Creator of life.” Stringing together religious beliefs and anti nuclear weapons sentiment has strengthened the Plowshares movement’s goal of waking up everyday citizens to the atrocities and horrific possibilities of nuclear warfare.

History of Antiwar Activism

Some of the first antiwar protests in Kitsap County were lead by Edison Fisk during the Vietnam War. The protests “were led by “Pinky” Fisk, and usually only attracted four or five people at most. But they were Kitsap County’s first antiwar protests, and Fisk was arrested three or four times — once for disturbing the peace when he paraded around with a protest sign proclaiming, “The Grateful Society: Bombs, Bullets, Battleships and Bullshit” (Our Campaigns). Fisk was arrested a few times outside of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton for offensive language on his sign and for “disturbing the public.” The charges were dropped and he got his sign back. Fisk’s protests were small, but monumental in that he paved the way for antiwar protests in Kitsap County (Our Campaigns).

As the Vietnam War ended, antiwar protests shifted from being anti-intervention to being anti-nuclear weapons, which made Kitsap a hotbed for political activism. The Pacific Life Community has been an active nonviolent antiwar activist group in Kitsap County since the 1970s. The PLC operates in a similar manner to Ground Zero, with extreme opposition to nuclear weapons but not interested in fighting violence with violence. In one of its first actions in the mid-1970s on Bangor base, “30 people were removed from the base and handed letters ‘barring their reentry,’ a typical first-offense penalty. They had crossed the fence with gardening supplies and proceeded to plant a vegetable garden and sow wheat along the base road before being evicted. The event was a success, as their action received press in newspapers as far away as Toronto.It was an encouraging beginning” (Ablao 2009).

Criminalizing Activism

The “Global War on Terror” since 2001 has redefined opposition against corporate militarism as a “terrorist” threat. This makes antiwar resistance work increasingly dangerous. Back in the 1960s and 1970s antiwar resistance was often repressed, but the repercussions were usually not as heavy. This makes resistance and activism look bleak in the 21st century, now that anyone can be considered a terrorist and faces dramatically worse punishment. As the police state becomes more militarized how will that continue to negatively impact future waves of resistance?

In the mid 2000s the Plowshares activist group broke onto Bangor Nuclear Base doing similar resistance work to the PLC group decades before. However, the Plowshares group was faced with charges quite a bit more harsh than a no trespassing letter. At the end of the trial, Judge Settle “pronounced their sentences: 15 months each for Father Kelly and Susan Crane, six months for Lynne Greenwald, two months for Sister Montgomery, followed by four months of house arrest, and three months for Father Bill Bichsel, followed by six months of house arrest. Judge Settle then considered whether to release the defendants as they awaited their prison terms. He asked each one if they would refrain from further protest, and self-report at the appointed time. None agreed” (Ablao 2009).

The repercussions faced by the PLC group in the 1970s and the Plowshares movement in the late 2000s highlights a fierce crackdown on antiwar protests. A “please, no trespassing” note, contrasted with many months in jail for nearly the same actions demonstrates heightened protection of military bases and strong repression of civilian activism. The Guardian observed that “an effective way of suppressing protest activity and creating an enormous burden for people who want to go out and express their concerns” (Levin 2018). The larger the threat becomes for activists, the fewer people are going to show up. Although the state has been conflating activism with terrorism for decades, recent crackdowns since the George W. Bush administration have the situation much worse.

The powerful website Defending Rights and Dissent elaborates on this message by saying “In this century the FBI used “domestic terrorism” as an excuse to investigate non-violent civil disobedience committed by pacifists and the material support for terrorism statute to raid the homes of anti-war activists” (Rights and Dissent). Opposing militarized forces has never been harder and more dangerous than it is today. With that being said this kind of antiwar activism has never been more important.

Political Dynamics in Kitsap County

Kitsap County is a highly dynamic social and political arena. The military presence makes it more conservative, though some of the smaller towns there are more “liberal.” I have been thinking about this dynamic probably since the beginning of junior high school or even before. Spanning across Kitsap County there are places such as Bainbridge Island that, for the most part, is home to many wealthy liberals. Just 10 or 15 miles from there a person can get a taste of Bremerton, home of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard (PSNS). Bremerton is a working-class community with plenty of jobs from a militarized economy.

Growing Up in Kitsap County

I grew up in one of the most dynamic towns in Kitsap County, Port Orchard. Examining the “pipeline” that many fellow students followed after high school is very telling of the social/political dynamic of the area. A large part of my graduating class (in 2012) went to nearby Bremerton to join the PSNS fleet of workers. To them, this was an opportunity to be set for life. They could work steadily, and most likely buy a house quite quickly after becoming employed, at least compared to other career pathways. The high school-to-military pipeline was highly prioritized at my South Kitsap High School, and fit very well with the “fight song” which is chanted towards rival schools during sporting events.

Then there were people like me that moved to Seattle right after high school (or Bellingham, Olympia, or Tacoma) because they felt a certain type of oppressive alienation living in such a conservative area. Also, plenty of students decided to go to Eastern, Central, and of course Washington State University. Parts of Port Orchard feel like a cool progressive island similar to Vashon, or maybe even little glimpses into the “utopia” of Port Townsend. But parts of Port Orchard are heavily dominated by the shipyard, a weapons-based economy, and a military presence that never stops looming.

Party Trends in Kitsap County

The Kitsap Sun, the local newspaper in the area, covers some of the political ideologies of Bremerton city council candidates. Suzanne Griffith, a potential council member for District 1 in Bremerton describes herself as a “progressive who supports human rights and workers.” “She worries that her neighbors are going to be priced out by people moving in from across the Puget Sound and wants to put the brakes on growth” (Fraley 2017).

The official Kitsap Republicans website states on its webpage, “We believe in Natural Rights, Individual Liberty, and a Constitutionally-limited government that protects the rights of the smallest minority – the individual – because #YouMatter. The Kitsap Republicans believe in reducing government intrusion in our lives, federalism, national security, private property, local control, taxation, human services, individual mandates, education, economic development, public protection, equal rights, FAITH, family integrity, natural resource conservation, and of course… reducing the national debt” (Kitsap Republicans).

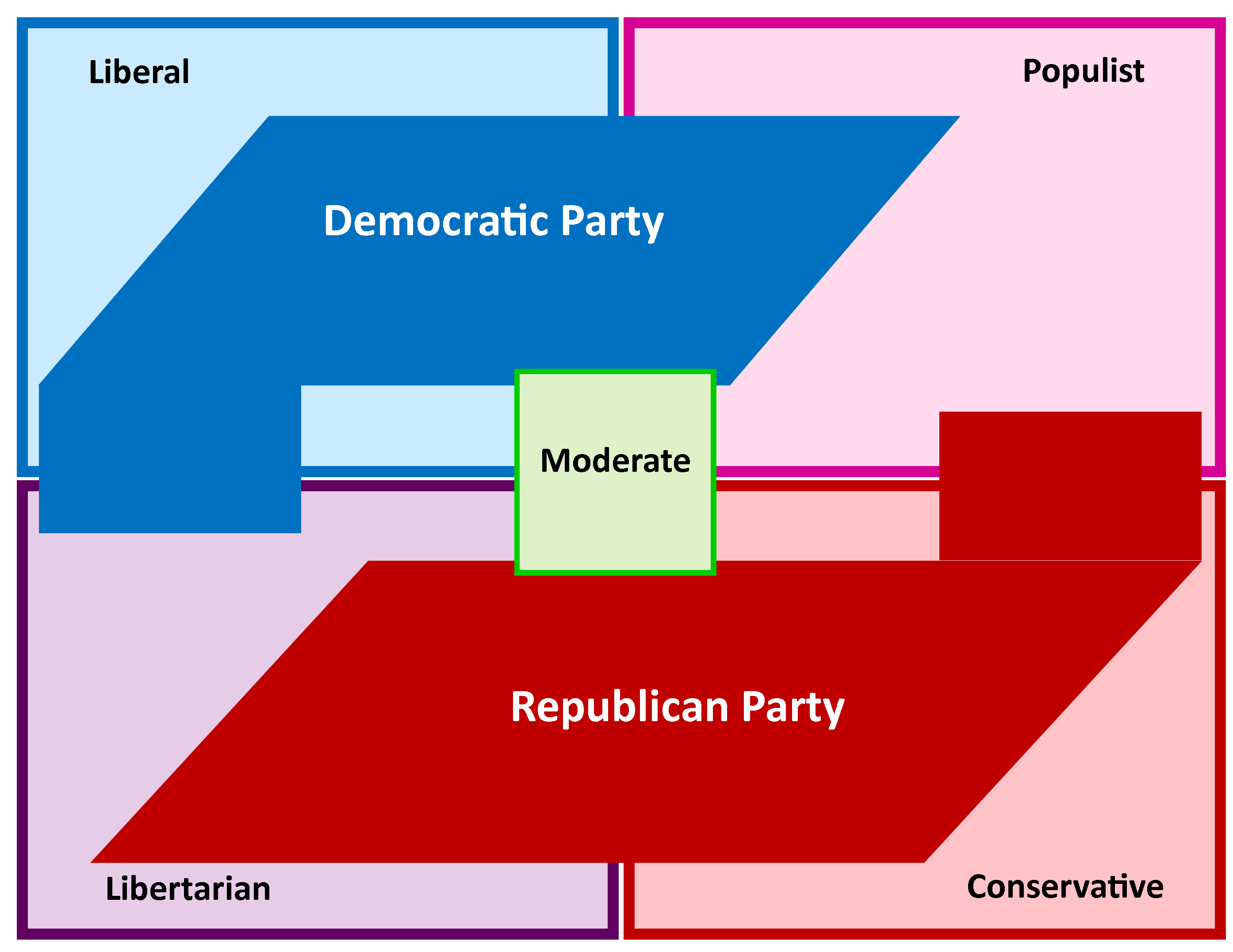

A Seattle Times article “Washington’s liberal counties are the ones growing the fastest,” noted that, “Along with King and Snohomish, seven counties voted for President Obama, recreational pot and marriage equality in 2012: Jefferson, Kitsap, San Juan, Skagit, Thurston and Whatcom. Combined, the nine grew 67 percent faster than the rest of Washington, and now account for 54 percent of the state’s population” (Balk 2016). This kind of statistic suggests that Kitsap is moving in a blue direction.

The 2016 presidential election showed how much Kitsap County is polarized. It was carried by Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, with 52.3 percent over Republican nominee Donald Trump, who earned 38.1 percent of the vote (Kitsap Sun 2016).

It may also be worth mentioning that Kitsap County borders Vashon Island, what some would call one of the most socially progressive areas in the state. The Washington Post reported that Crowdpac, a Silicon Valley startup, determined that Vashon Island is “the most liberal place in the country” (Balk 2016).

Bainbridge Island also impacts Port Orchard and the rest of Kitsap County. The Bainbridge Island Review notes that, “Nine out of every 10 Bainbridge voters supported the initiative to tighten state firearm regulations” (Kelly 2016). But while Bainbridge Island and other pockets (or bubbles) of liberalism sound “progressive,” there is ongoing critique of how “comfortable” white liberals are still pretty content with the status quo, so may not pose much of a challenge to the militarized social order (Mudede 2016).

Conclusion

I do not think the future of Kitsap County will look much different than it does right now. In fact, Kitsap is becoming more and more developed as more people cannot afford to live in Seattle. Some of these people moving from the city to Kitsap County probably do not want to live near all of this military infrastructure but do not care, or feel powerless. These are the kind of people who soon to dominate Kitsap.

For example, “Amy Staupe and Chris Roy were tired of city life. The longtime Los Angeles residents took an eye-opening trip to New Zealand in 2009. While there, Staupe said, ‘We realized there was a different way to live.’ The couple decided to trade their city’s dense pollution and oppressive heat for ‘seasons, trees and air that wasn’t chokingly horrible.’ Staupe also wanted more space for their future family to roam….. Returning from New Zealand, the question became: Where can we find that without leaving the country?’” (Dalton 2018). The couple now lives in Port Orchard and works in Seattle.

With the highly militarized economy that looms over and controls the area I do not think activist groups are going to change the area dramatically, although maybe they will shed light on issues created by the military in the area. It seems much more likely at this point that climate change will make Kitsap County inhabitable before the military changes its ways.

Sources

Ablao, Sue. (2009, November 2). Plowshares Action At Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor In Washington State. GreenMac.

Ablao, Sue. (2009, November 20). 5 People Arrested on Naval Base Kitsap – Bangor. Disarm Now Plowshares.

Balk, Gene. (2016, July 3). Washington’s Liberal-voting Counties Are the Ones Growing the Fastest. Seattle Times.

Best Places. (2016). Politics & Voting in Kitsap County, Washington.

Carter, Mike. (2010, September 3). 5 Antiwar Protestors Indicted in Bangor Naval Base Incident. Seattle Times.

Casserly, Brian. (2004, Summer). Anti Nuclear Activism: Special Section. University of Washington.

City Data Forum. (2014, April). Which Seattle suburbs are the most conservative?

Dalton, Melissa. (2018, January 30). A Modular Home on the Kitsap Peninsula. 1889 magazine.

Dambergs, Lucas. (2018, February 23). Anti Nuclear Peace Activists Break onto Bangor Base. HistoryLink.

Drosendahl, Glenn. ( ).

Dzama, Pam. (2003, November 19). A pseudo-rural Fortress Kitsap? I hope not. Kitsap Sun.

Eiger, Leonard. (2010, September 6). Disarm Now Plowshares Indicted for November 2009 Witness. The Nuclear Resister.

Fraley, Josh. (2017, October 18). New Faces Could Swing Bremerton Council’s Political Dynamic. Kitsap Sun.

Kelly, Brian. (2016, November 11). General Election Precinct Analysis: Bainbridge Goes Big on Gun Control. Bainbridge Review.

Kitsap Republicans. (n.d.) Home.

Kitsap Sun Staff Report. (2016, November 9). Visual Vote: Maps Detail Election Night Outcomes. Kitsap Sun.

Our Campaigns. (n.d.). Fisk, Edison “Pinky.”

Parrish, Will, & Levin, Sam. (2018, September 20). Treating Protest As Terrorism’: Us Plans Crackdown on Keystone XL Activists. The Guardian.

Rights and Dissent. (n.d.) Activism Is Not Terrorism.

South Kitsap High School. (n.d.) SKHS Fight Song. South Kitsap School District.