Clayton Roessle

This study examines the involvement of the Washington military base formerly known as Fort Lewis in the Gulf War and Iraq War; the base transitioned to become Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM) in 2010. Of key importance is examining the lethal and nonlethal means by which Fort Lewis’ military forces, under the collective aegis of Task Force Olympia, fought the various Iraqi insurgencies within their zones of control and worked to bring the country into the control of the Coalition-installed government.

The study covers the preparations made for training and constructing the Stryker vehicles that Fort Lewis would be known for, the actions of Stryker and non-Stryker brigades during the Iraq occupation, and their involvement in the infamous systems of detention and torture. The sources for this study come from military-aligned documents and a former counterintelligence agent who was present in Mosul during the occupation.

Gulf War, 1991

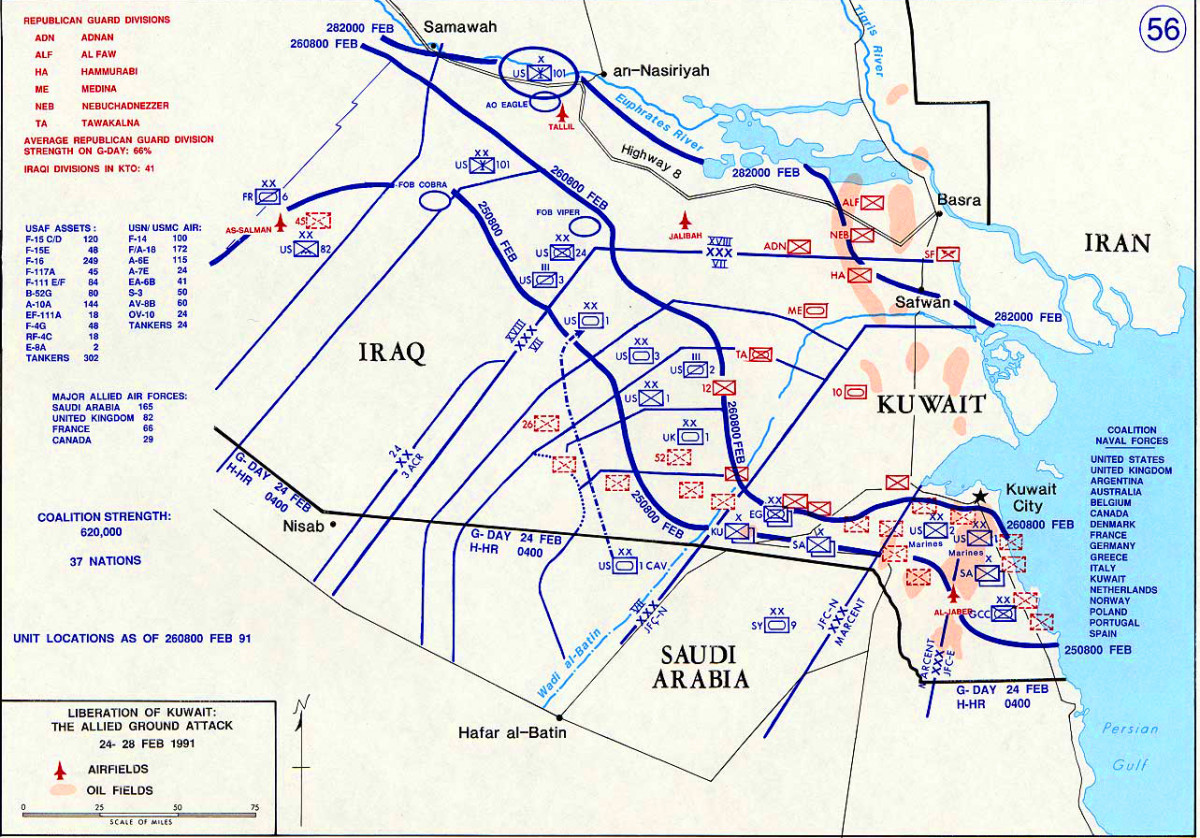

Overall, few units from Fort Lewis participated in the Gulf War, with most U.S. forces coming from XVIII Airborne Corps and VII Corps, alongside the I Marine Expeditionary Force and the host of other coalition allies. However, the 593rd Expeditionary Sustainment Command provided logistical support for the ground operations in the Kuwait and southern Iraq area, as well as some 12 support troops.

“On Aug. 31, 1990, the 593rd Area Support Brigade deployed to Saudi Arabia for participation in operations Desert Shield, Desert Storm and Desert Farewell. In addition, the 593rd Area Support Brigade deployed on Dec. 24, 1992, to Somalia for Operation Restore Hope” (JBLM n.d.).

Northwest Military reported that the 593rd Area Support Group left in August 1990, just after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. C-141s deployed from McChord Air Force Base with soldiers and equipment as an air bridge to the Middle East. The first combat unit to deploy was the 1-9 Cavalry, followed by 12 support units.

I Corps also provided leadership to the war. “Commander Lt. Gen. Calvin Waller named deputy commander of the operation, serving directly under Gen. Norman Schwarzhopf (former I Corps commander at Fort Lewis) Major Gen. Paul Schwartz, then deputy commander of I Corps, acted as liaison for the Coalition Forces during the war.”

“Waller left in November 1990 and returned to Fort Lewis March 12, 1991. He told the assembled crowd “’I knew it was raining today and it is the best sight I have ever seen. Saddam Hussein got his butt kicked.’” (Swarner 2017).

Creation of the Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2003

“In October 1999 Chief of Staff Gen. Eric K. Shinseki announced that the Army will develop two technology-enhanced, fast-deployable and lethal brigades at Fort Lewis WA using knowledge gained by Force XXI experiments and off-the-shelf technology available from the private sector” (Global Security n.d.).

In November 1999, two brigades under the command of I Corps, based in Fort Lewis, were slated to transition to “lighter, more mobile units capable of deploying within 96 hours.” The new brigades would consist of 3 mechanized infantry battalions, as well as a “reconnaissance intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition squadron” (RSTA), whose purpose was both to provide support for the mechanized infantry and to provide stability in “hot spots” across the world. These brigades would later be known as the Stryker Brigade Combat Teams (Global Security n.d.).

In November 2000, General Dynamics Land Systems, the military branch of General Motors, was awarded a military contract to design and construct Stryker vehicles for the Army. The vehicle was intended to strike a balance between light and heavy infantry, ensuring maximum “lethality and survivability” while also being fast, agile, and able to be rapidly deployed anywhere in the world.

The order was for “2,559 vehicles in 10 different configurations (Infantry Carrier Vehicle, Anti-tank Guided Missile, Mortar Carrier, Command Vehicle, Reconnaissance Vehicle, Engineer Squad Vehicle Medical Evacuation, Fire Support Vehicle, NBC Reconnaissance Vehicle, and Mobile Gun System) full logistics support to include spare parts” (General Dynamics Land Systems 2006).

- The vehicle had to be able to load onto a C-130 aircraft for transportation

- It had to be able to carry a nine-person squad (depending on vehicle variation) fully equipped.

- The primary armament had to be able to penetrate bunkers and reinforced walls.

In 2001-05, General Dynamics was awarded $3,619,200,000 for the completion and production of these vehicles, with a general contract value at $4.4 billion. In February 2003, the first vehicles would be distributed to soldiers at Fort Lewis, followed by their deployment into Iraq in December 2003 (General Dynamics Land Systems 2006).

General Dynamics was commissioned to create 10 different variants of the Stryker vehicle, collectively called the IAV (Interim Armored Vehicle) family of vehicles. The Stryker Brigade Combat Team Project Management Office provides details regarding the function of each of these variants, alongside pictures and descriptions of their arms, armor, transportation, and communication capacities.

The variants are as follows: the Infantry Carrier Vehicle (ICV), Anti-Tank Guided Missile Vehicle (ATGM), Commander’s Vehicle (CV), Engineer Squad Vehicle (ECV), Fire Support Vehicle (FSV), Mortar Carrier (MC), Medical Evacuation Vehicle (MEV), Reconnaissance Vehicle (RV), Nuclear, Biological, Chemical Reconnaissance Vehicle (NBCRV), and Mobile Gun System (MGS) (Project Management Office).

Soldiers on the ground saw the armor that was provided by the Stryker as insufficient for combat. They were especially concerned with the ability of Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) and Rocket-Propelled Grenades (RPGs) to penetrate Stryker armor. Because of this, metal slat armor was installed onto the Stryker vehicles upon arrival in Kuwait for extra protection. Installation of the slat armor proceeded at a rate of about 40 vehicles per day (Center for Army Lessons Learned 2004, 52). The armor adds an additional 5,000 pounds to the weight of the vehicles, making them too heavy to be transported by a C-130 (Schmitt 2003).

The Initial Impressions Report detailing the ‘lessons learned’ for the 3rd Brigade, 2nd Infantry, mentioned that the slat armor was only installed onto the Strykers after they had arrived in Iraq, meaning that they were not trained to handle the added weight on the vehicle, leading to many accidents. The Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) did not conduct Stryker driving courses, meaning that “virtually all driving skills are developed in Iraq during regular operations,” often under stressful circumstances (Center for Army Lessons Learned 2004, 64).

The Report described some of the problems associated with the installation of slat armor. Some were basic design flaws, such as fuel spouts or tow bars not being long enough, but the addition of slat armor caused many problems to emerge that were not planned for in the original design, especially with soldier recklessness often causing accidents and breakdowns.

“Slat armor did not significantly impact Stryker handling, off or on roads, during the dry season however, the additional weight significantly impacts the handling and performance during the rainy season. Mud appeared to cause strain on the engine, the drive shaft, and the differentials. During a mission in Tall Afar, one Stryker had two driveshafts and a differential broken while trying to maneuver in the mud. The slat armor also bends, with continued operation and during accidents and roll-over incidents, covering vehicle escape hatches and can block the rear troop door in the ramp” (Center for Army Lessons Learned 2004, 49).

Iraq Invasion, 2003

Though the U.S.-led Coalition planned extensively for troop deployments during the invasion, there was little plans for how it would maintain stability after the war had concluded.

A total of four Stryker brigades were deployed by Fort Lewis/JBLM in Iraq over the course of the war. The 5th Stryker Brigade, 2nd Infantry was also trained at JBLM, but was deployed instead to Afghanistan, where the brigade was embroiled in controversy for its involvement in the “Kill Team” which executed several villagers (Ackerman 2010). The Stryker Brigades which were deployed to Iraq were the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Stryker Brigades, with the 1st under the 25th Infantry Division and the rest under the 2nd Infantry Division.

“On Feb. 5, 2004, Task Force Olympia was activated, a sub-element of I Corps headquarters with the mission to command forward-deployed units in Iraq… Task Force Olympia’s subordinate units included the 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division, which deployed for Iraq Nov. 8, 2003, and returned to Fort Lewis after one year of combat duty; and the 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry Division… A brand-new unit ready to make history then uncased the colors of its new designation on June 1, 2006 — the 4th Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division.” (MyBaseGuide 2017).

Early in the occupation, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published hundreds of articles listing the deaths of Fort Lewis/JBLM soldiers stationed in Iraq. At the time, there was little coverage of abuses committed by Fort Lewis soldiers against the people of Iraq, ostensibly to maintain support for the war effort.

Stryker Deployments

“The 3rd Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division at Fort Lewis was chosen to be the nation’s first combat team to go through transformation because of the base’s large training ranges and ability to transport troops quickly through nearby McChord Air Base and the Port of Tacoma. After 18 May 2000, the Brigade began its transformation by fielding new digital equipment and the U.S. Army’s first Stryker Combat Vehicles. This transformation culminated on 23 September 2003 with the Brigade’s certification” (Global Security n.d.).

The 3rd Brigade, 2nd Infantry, was among the first two brigades selected to be converted to Strykers, alongside the 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry in Hawaii. Repeatedly emphasized is that the Strykers, being lighter and more mobile than tanks and able to transport larger squads than other vehicles, will be capable of global intervention at any time. Their purpose is to fill the gap between “early-entry forces and heavier follow-on forces.” Their equipment emphasized lethality and agility (Global Security n.d.).

The 3rd Stryker Brigade, 2nd Infantry arrived in Kuwait after a three week voyage, arriving to Camp Udari on November. Equipment was moved from cargo holds for transport to Camp Udari in Kuwait. They arrived on November 12th, 2003, and according to the U.S. Army in the Iraq War were immediately directed to Samarra and Balad to combat the insurgent uprising during the holy month of Ramadan, which had already targeted the U.S.-led Coalition through car bombings (some suicidal), firing on Coalition militaries, and attacks on the new Iraqi government, with much of their membership coming from members of Saddam Hussein’s old regime that were ousted by the new government (Rayburn & Sobchak 2019, 231)

The 3rd Brigade, 2nd Infantry was sent to relieve the 101st Airborne Division, which was based in Mosul and had participated in the March 2003 invasion of Iraq, immediately after a December 10 raid which captured 600 “suspected insurgents” and destroyed “safe houses.” The 3rd Brigade was to continue this work, first conducting patrols and raids in Samarra and Baghdad, then sweeping through Samarra on December 17, in what was called Operation Arrowhead Blizzard, to target former officers and Ba’athists. Their efforts were measured by the numbers of people detained, routes cleared, weapons seized, or intelligence required. Military operations had little grasp of how to concretely reduce the level of violence, and their actions usually inflamed conflict rather than dissuaded it.

On that note, the 3rd Brigade’s raid in Samarra on December 16 detained 15 high-value targets, 111 “suspected insurgents,” and 26 major weapons caches. Sobjack and Frank reflect that the units had little information about who exactly they were fighting, meaning that the raids often resulted in small setbacks for insurgents rather than concrete reductions in violence (Rayburn et al 2019, 233). Considering what Joshua Simpson said in the interview later on this webpage, many of the “suspected insurgents” were likely at the wrong place at the wrong time, culminating in their processing through the brutal U.S. detention system and in growing popular anger against U.S. presence in the country.

2nd Rotation

The U.S. military opted for six-month rotations instead of having soldiers in-country year-long. It believed it was this that caused the failure in Vietnam, and the Pentagon did not want to repeat similar errors.

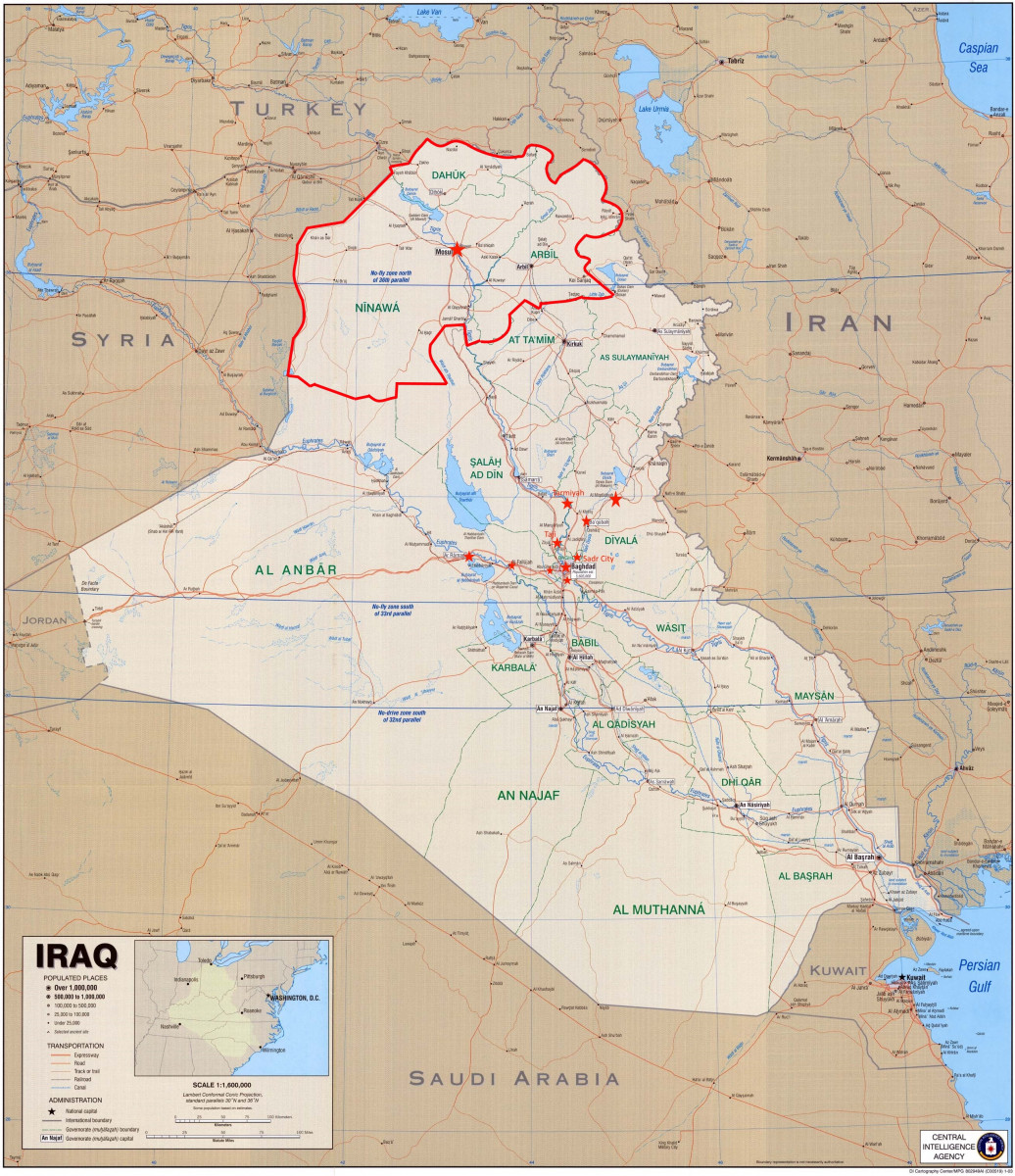

In early 2004, many brigades were slated for rotation with other units deployed to Iraq. During this time Task Force Olympia was renamed the Multi-National Brigade-Northwest (MNB-NW), which included a total of 10,000 troops, including the 3rd Brigade, 2nd Infantry Strykers under the command of Brigadier General Carter F. Ham. It was directed to replace the 101st Airborne Division, whose area of operations included the provinces of Ninewa, Dahuk, and Erbil. MNB-NW was less than half the size of the 25,000 soldiers of the 101st and lacked many of the same capabilities, but the area was deemed stable enough for the reduction, and a large portion of the units were sent without their full compliment of equipment (Rayburn et al 2019, 260).

Under the policy of ‘de-Ba’athification’ by the U.S.-run Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), many officials of the former Ba’ath Party administration and military were not included in the new government, with this and other structural adjustments resulting in high levels of unemployment for the Iraqi Sunni population. This only gave more manpower and equipment to the Sunni insurgency. They hid among the population, attacking critical infrastructure such as oil and electrical grids to turn the people against the Coalition. Some Sunni jihadists, such as Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, also wished to forment the growth of a sectarian civil war between Shi’a and Sunni (Rayburn & Sobchak 2019, 260)

The growing insurgency proved that the second rotation of U.S. deployments would not go smoothly, with April 2004 being the worst month of the war, ending with 137 U.S. soldiers killed. A Stryker battalion from 3rd Brigade, 2nd Infantry was lent to the 1st Armored Division, leaving Task Force Olympia further overextended and understaffed for the vast territory it was supposed to control. While an uprising by Shi’a leader Moqtada Al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army took place in the south, insurgents gradually streamed north on the path of least resistance. Sunni jihadists took control of a university which the Coalition helped to fund, as well as emptied the Iraqi Army units through sheer intimidation.

“By midsummer 2004, Zarqawi’s fighters, Ansar al-Islam, and other insurgent groups had taken control of the strategic city of Tel Afar, about 80 kilometers west of Mosul astride the main highway to Syria.” (Rayburn et al 2019, 351). The brigade commander called to the rest of the coalition for aid, but it was not forthcoming due to fighting elsewhere, and in mid-2004 Mosul was taken. A force of 2,500 rebels went from police station to station, forcing the newly built security forces out to disarm and disband them. The 3rd Brigade, 2nd Infantry operated for 12 months before redeploying back to Fort Lewis in October, 2004 (Global Security n.d.).

“On May 17, 2004, the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division received the order to deploy to Iraq with less than three months’ notice; additionally the unit was informed that it would redeploy to Fort Carson, Colo., not back to Korea. From August 2004 to August 2005, 2nd Brigade Soldiers fought in Operation Iraqi Freedom in the first combat deployment for the brigade’s battalions since the Korean War. The brigade saw active combat from Ramadi to Fallujah to Baghdad before redeploying to Fort Carson” (MyBaseGuide 2017).

“The Brigade was made up of infantrymen, M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicles, mechanics and engineers worked together to complete the mission. The unit’s mission was to search and secure the enemy’s fire power. The unit did a lot of cache sweeps, mostly through the countryside and in houses, trying to push out the insurgents. They usually found some buried caches, mortar rounds or booby traps” (Global Security n.d.).

“They were very successful. The enemy, however, became smarter and IEDs and mines became prevalent. Once the field had been cleared, the soldiers and Bradleys would conduct their sweeps in factories, buildings and homes. They would secure the main support route that ran from Fallujah to Ramadi. After the all-clear was given, they would conduct raids in the area” (Global Security n.d.).

The 3rd Stryker Brigade, 2nd Infantry redeployed to Iraq from June 2006 to September 2007. The goal was assisting Iraqi security forces with counterinsurgency in Nineva province, and thirteen months of “full-spectrum” operations throughout Mosul and Nineva provinces.

“The Brigade’s actions, in conjunction with Iraqi Security Forces, defeated Al Qaeda-affiliated insurgents in the Brigade’s battle space, suppressed Shia extremist militias, bolstered Iraqi civil government and security force capabilities, and protected critical infrastructure” (Global Security n.d.).

“The Arrowhead Brigade returned to Iraq in June 2006 for what was originally to be a yearlong deployment to Mosul. They were later sent to Baghdad, saw their tour extended to 15 months and were used as a strike force to attack in some of the country’s toughest areas. The entire brigade served in Baqouba in Diyala province, where they forced Al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) from what the group called the capital of its new Islamic republic” (MyBaseGuide 2017).

In October 2006, the new 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division returned to Iraq as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom VI. After the deployment the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division was subsequently inactivated in April 2008. During that tour in Iraq, the brigade destroyed the insurgency in Ramadi as well as serving in other areas such as West Baghdad and Sadr City. Two soldiers in the brigade earned the Distinguished Service Cross for actions during this tour (MyBaseGuide, 2017).

“2nd Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division was subsequently inactivated in April 2008, its personnel were reflagged as the 4th Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division. The 5th Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division at Fort Lewis, Washington, was then expected to eventually be reflagged as the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division” (Global Security).

4th Stryker Brigade Combat Team and the “Surge,” 2007

The 4th Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry deployed to Iraq as part of President George W. Bush’s ‘surge’ strategy, with plans to send 20,000 additional U.S. soldiers to Iraq. It was one of five brigades slated for deployment “and became the first Stryker Brigade to deploy with all ten variants of the Stryker combat vehicle. During more than thirteen months of continuous, full-spectrum operations, the Raider Brigade successfully conducted nine brigade-level operations and more than 550 battalion- and company-sized operations throughout the Baghdad Northern Belt and in Diyala Province.”

The Stryker deployments from the Ports of Olympia and Tacoma caused massive protests (see Civilian Dissent). They also came at a time of mounting critique and unrest from Fort Lewis military personnel (see Military Dissent).

This unit was activated in June 2006 and deployed to Iraq in April 2007 as part of Bush’s “Surge” strategy, being newly activated alongside several other units at other bases. It was the first unit to field the Land Warrior digital communications system (Global Security n.d.).

Operation Raider Isolation – June 2007

Spearheaded, by 2-1 Cavalry to prevent the exfiltration of Al Qaeda fighters from the city of Baqubah. 3rd Brigade, 2nd Infantry cleared Baqubah in Operation Arrowhead Ripper.

Operation Raider Riviera – September 2007

The deliberate clearing of Al-Qaeda strongholds in Tarmiyah. Detained 500 people, solidifying Iraqi security infrastructure and patrolling for IEDs. Transferred control of Tarmiyah and Husayniyah in December, 2007.

Operation Raider Reaper – December 2007

Seizure of additional areas from Al Qaeda control in the Baqubah region. The brigade then shifted focused to the Diyala River Valley between the cities of Dali Abbas and Muqdadiyah. Followed up with operations to clear the regions south of Buhriz and south of the city of Balad Ruz. Opened Route Vanessa between Baqubah and Khan Bani Sa’ad.

Return to Fort Lewis – 1 June 2008

The operations resulted in 1,700 personnel detained and more than 600 insurgents killed or wounded and removed 200 high-value individuals through intelligence-driven raids. Cleared 11,250 km of routes and 1,295 IEDs. Found 550 enemy weapons caches.

This began a reset period that would last six months, repairing and replacing equipment in preparation for another deployment (Global Security n.d.).

The 3rd Stryker Brigade, 2nd Infantry returned to Iraq in August 2009 to Diyala province, closing down U.S. facilities in advance of the war’s end. Mission completed in July 2010 (Global Security n.d.).

Return to Iraq – September 2009

2nd Brigade, 1st Infantry Div transferred authority of western Baghdad to the 4th Brigade. With this Task Force Viking was formed, with an area of operation from Baghdad International Airport to the Tigris River in the east (excluding the Green Zone). Area around Abu Ghraib, a prison reputed for torture and human rights abuses by the CIA and soldiers.

The brigade also supervised the Iraqi national elections and facilitated the transfer of security stations to the Iraqi government.

The brigade, alongside USAID and the Army Corps of Engineers, developed reconstruction projects in “Western Baghdad, Abu Ghraib, Taji, and Tarmiyah… repairs of medical clinics and schools, solar lights for streets, drinking water pumps, and filtration systems , electrical projects, sewage treatment plants, agribusiness and local business grants. 83 projects totaling 14.5 million dollars (Global Security n.d.).

2,000 Raiders departed via a tactical road march from Victory Base Complex and Camp Taji in August 2009. In “The Last Patrol,” soldiers drove 360 vehicles, including 320 Strykers, 360 miles from Baghdad to Kuwait, similar to how units first entered Iraq.

After participating in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, the unit was deactivated in March 2014 (Global Security n.d.).

Iraq Reconstruction

From the perspective of the 4th Stryker Brigade, 2nd Infantry, Craig Collier wrote his report “Now That We’re Leaving Iraq, What Did We Learn?” “Economic development may have played a role, but our lethality was the most important factor […] We should not feel ashamed that raditional combat operations worked in Iraq. After all, we put an awful lot of effort into ensuring that our soldiers are the most lethal on earth.” (Collier 2010).

Battalion commanders and executive officers were given responsibilities as “resource managers, directorates of contracting, and directorates of public works” with inadequate training. Many civilians served under the brigade. The brigade swept for IEDs, fed equipment and knowledge to Iraqi police, and did physical security at critical infrastructures. “Many local nationals were not coming to work because of threats they, or their family, received because they work for United States forces” (Center for Army Lessons Learned 2004, X).

When the Coalition Provisional Authority Inspector General (CPA-IG) made its first trip to Iraq, it discovered that the more than $20 billion in Development Fund for Iraq (DFI) funds had very little oversight in their dispersal, after being airlifted from Maryland and deposited into the Central Bank of Iraq. Efforts to rebuild infrastructure were often steeped in corruption and efforts to create “feel good” projects that would serve as good media for the soldiers without really helping the situations of Iraqis (Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction 2012, 5).

Money would often be spent without any tangible results or would be “lost.” Several soldiers have been found to have stolen money from the reconstruction funds, such as an Army Captain Dung Nguyen, who was found to have stolen $690,000 during his 2007 tour in Iraq (Associated Press, 2009). U.S. Army Major Kevin J. Schrock also stole $47,641 while he was deployed with the 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry Division in Mosul, during its tour in 2004 (Pulkkinen, 2011). If such large amounts could be stolen by U.S. soldiers with consequences only years later, a large portion of the money that was meant for distribution probably did not end up in the hands of the war-battered Iraqis.

The 3rd Stryker Combat Brigade, 2nd Infantry decided to fund the construction of a school. The funds dispersed evidently had not provided supplies for the school, and there were also no students during the brigade-sanctioned opening event.

“An embedded media representative was staying with elements of the brigade and had been granted access to an event where school supplies were to be handed out to needy students. The unit took the reporter to a school which they had recently built. When they arrived they were surprised to find that no children were present and that an Iraqi family was homesteading in the building. The Iraqi police were unwilling to remove the family and no school supplies to be issued. Fortunately the reporter elected not to cover the event, which could have made us look bad, since we didn’t know what was going on with the school after we funded its construction. The Iraqi police were unwilling or unable to support us and the supplies that we purchased were never distributed to the children. The reporter understood what had happened and had other good coverage to use and rather than airing any of this event” (Center for Army Lessons Learned 2004, 39).

Torture and Detention, an Interview with Joshua Simpson

On January 28, 2019 I conducted an interview with Joshua Simpson, a former Army counterintelligence agent who was stationed in Mosul in 2004-05, during what were described as the “worst years of the occupation.” They deployed with the 25th Infantry division (“Tropic Thunder”) in 2004, until 2005 when they returned.

Despite the fact that soldiers thought Joshua was linked to the Criminal Investigative Division and were more likely to avoid them, they saw many kinds of abuses in their position as a counterintelligence agent.

Those with the combat teams that worked in counterinsurgency would patrol the neighborhoods in their “Area of Responsibility,” often detaining random people for “spying” or harassing others. Soldiers could interrogate civilians without any record or accountability. The number of people detained was a statistic similar to body counts in Vietnam, supposedly measuring the numbers of captured terrorists. Joshua would go on to say that probably fewer than 5% of the population was actively engaged in fighting U.S. soldiers.

One particular kind of abuse that Simpson described was detainment, where people would be shipped to detention centers for interrogation and torture. Often the U.S. would give its prisoners to Iraqi and Kurdish militia groups, knowing well they would be tortured. This was done to keep the soldiers from getting their hands dirty, although the U.S. often also tortured people.

An important example of U.S. torture practices, and one that was scandalously publicized in the media, was the abuses at the Abu Ghraib Prison. Iraqi detainees were stripped naked and were covered with black hoods. Some were thrown onto piles of other naked men, others were forced to masturbate with each other, and occasionally electrodes were applied. Other methods included “prolonged sleep deprivation, beatings, exposure to loud music and prolonged periods of being covered with a hood” (Indybay 2004).

Despite taking the brunt of the blame for the conditions in the prison, the soldiers placed in charge of interrogation were encouraged by higher-ranking officers, who were looking for fast results on interrogation without respect to international law regarding torture. One of the implicated soldiers, Staff Sgt. Ivan “Chip” Frederick, said “We had no support, no training whatsoever, and I kept asking my chain of command for certain things, rules and regulations, and it just wasn’t happening.” He did not see a copy of the Geneva Convention rules for handling prisoners until after he was charged.

CONTENT WARNING (Graphic torture, nudity, and sexual violence) : (Photos of US Torture of Iraqi Prisoners At The Abu Ghraib Prison In Iraq).

Detainee-holding facilities were different for each Forward Operating Base (FOB) for each subordinate battalion task force. 2nd Battalion, 3rd Brigade FOB “had a large holding facility with separate holding areas, a separate interrogation room, and space for interrogators to confer and develop interrogations, an entrance way to the facility equipped with flood lights, and a location that offered cover and concealment.” Another battalion had a single room for holding detainees, to which it said “this configuration limited interrogation techniques…” (Center for Army Lessons Learned 2004, 35).

The purpose of detention and interrogation was to get informants that could feed information to the military, either through bribery, threats, or questioning. This was part of the reason for the constant patrols.

I asked if they could tell me more about their experience with the Stryker vehicles. One of the main reasons that Strykers were preferred over the M2 Bradley was their increased resistance to IED (Improvised Explosive Device) explosions. They also allowed soldiers to concentrate in larger numbers and deploy all at once, and in that capacity the Stryker was primarily a transport vehicle. As resistance to the occupation spread, soldiers grew more wary, adding additional armor in the form of metal slats in order to withstand the IEDs and Rocket-Propelled Grenade (RPG) attacks.

I asked about how much of the training that soldiers received at Fort Lewis prepared them for the war. Simpson responded by saying that training was more about combat than counterintelligence. I asked Simpson to describe the tasks involved with the counterintelligence work they performed while part of the 1st Stryker Brigade, 25th Infantry. Simpson said that they mainly would interrogate prisoners from raids, using usually the least brutal methods of information gathering. They would also work to convince people to act as informants for the brigade. They would constantly be making reports on the intelligence that they gathered, in what they described as a “constant workload.”

The information they were seeking was usually looking for people in neighborhoods who were acting suspicious, looking to gauge the sentiments of the population towards U.S. forces. Sometimes people would feed false information about their neighbors if they did not particularly like them.

I asked if they could describe life for Iraqis before and after the war. They said that the country was much different before sanctions were imposed by the U.S. and the U.N., and ten years of sanctions made it “very hard to get basic necessities.” People acting against the U.S. forces would rarely target them directly, more often they would fight the weaker Iraqi army and the Kurdish peshmerga units, though sometimes they would lob mortars at the soldiers.

Simpson described how things were much different when soldiers first arrived in Iraq. It was apparently a more laid-back atmosphere at the beginning of the occupation, with soldiers expecting to be welcomed as liberators, compared to later on when widespread opposition to the occupation would erupt, both internationally and within the country. This is reflected in the ideas of the war’s leadership, in the U.S. Army in the Iraq War.

“Decision makers believed the United States would not need a large number of forces because of the seemingly successful precedent set in Afghanistan: that U.S. forces would be welcomed as liberators, and that the Iraqi Army would help provide security under a new, more enlightened Iraqi Government. Based on these two assumptions, there was no need for U.S. forces to conduct large-scale security operations” (Rayburn et al 2019, 36).

A Look at Patrols

Soldiers would also set up checkpoints and roadblocks to control traffic during their operations. A photographer from the Guardian, Sean Smith, followed a battalion from one of the Indianhead brigades from the 2nd Infantry Division, witnessing them detaining a whole household that was near a Bradley full of U.S. soldiers that was destroyed by an Improvised Explosive Device (IED). Afterwards they sent interrogators to look for information about the bomber. (Smith, 2007).

Spc. Lake from the 4th Platoon Apache Company Strykers had a chance to speak: “You’ve got grenades going off, you’ve got an IED blowing up your vehicle… and then you’re expected to go back in those 4 to 5 hours and relax, come back out and do another 6 hours. You just don’t have time to do it, your body never gets to come down, you’re always on that heightened sense of alertness, you don’t have the rest, the comfort zone I guess you could call it, to where you know you’re back on the FOB [Forward Operating Base] you know you can relax. You just don’t have time, we’re not given that time to recuperate from being out there for 6 hours, and we have to go back out and deal with another 6 hours. Just constant, we never get a break” (Smith 2007).

Conducting random house checks, find a frightened elderly women shouting for peace in Iraq, demanding the soldiers leave. She said “I’m so paralyzed with fear, I can’t even stand up” as the 4th Platoon searches her house.

Later, they saw a car driving around, and they tried to demand that the driver stop. When the driver didn’t stop, they shot him and then took him to the house of the woman. They would later find out by questioning the neighbors that he was a taxi driver.

|

|

Timeline of Recent Iraqi History

1912: The Turkish Petroleum Company is formed in Britain (Metz, 1988).

1918: World War I ends, Britain and France occupy much of the former Ottoman Empire, with the French taking both Syria and Lebanon and the British receiving Egypt, Palestine, Iraq, Jordan, and several other areas, in the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

1921: Faisal bin Hussein bin Ali al-Hashemi is crowned King of Iraq by the British occupiers, after threats of revolt from Iraqis under the British Mandate

1925: A concession to the Turkish Petroleum Company in Iraq is granted, giving shares to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (now British Petroleum/BP), the Dutch Shell Group, CFP (Commercial Forged Products), the Near East Development Corporation (representing the five largest American oil companies), and Caluste Gulbenkian, owning 5% and being known as “Mr. Five Percent” (Metz, 1988).

1929: Turkish Petroleum Company is renamed to the Iraq Petroleum Company.

1932: The British mandate ends and Iraq becomes independent.

1941: Britain reoccupies Iraq after a pro-Nazi coup.

1955: The pro-British Baghdad Pact is established between Turkey, Pakistan, Iran, and Iraq, but is greatly unpopular with most Iraqis.

1958: The monarchy of Iraq is overthrown in a left-wing military coup, producing an Iraqi Republic led by Abd al-Karim Qasim, who is made Prime Minister.

1963: Qasim is ousted in a coup by the pan-Arab Ba’ath Party

1972: The Iraq Petroleum Company is nationalized

1979: Saddam Hussein, the leader of the Ba’ath Party, becomes president of Iraq

1980-1988: The Iran-Iraq War begins, with Saddam Hussein invading revolutionary Iran. The war would end in a stalemate and inflict social and economic hardship on both countries.

March 16th, 1988: Saddam, in response to uprisings by Kurdish peshmerga rebels in the town of Halabja in northern Iraq, drops bombs containing poisonous mustard gas and nerve gas, killing thousands and injuring thousands more.

August 2, 1990: Iraq invades Kuwait and annexes it, after tensions over alleged oil overproduction end in war. The U.S. initiates Operation Desert Shield.

February 1991: An international coalition led by the U.S. initiates the Gulf War against Iraq, in Operation Desert Storm.

January 17th, 1991: Operation Desert Storm bombing begins, with the U.S. backed international Coalition invading Iraq.

February 28th, 1991: After 100 hours of ground troop advances, Operation Desert Storm ends with a decisive victory by the Coalition. Saddam proceeds to crush a Shi’a uprising in southern Iraq.

October 31st, 1998, Iraq Liberation Act was signed into law by President Clinton, openly advocating for regime change in Iraq based on the alleged failure of Saddam Hussein to reveal his Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs) for investigation. Clinton bombs Iraq in Operation Desert Fox.

January 20th, 2001: George W. Bush was inaugurated as president, promising a more aggressive policy against Iraq leading up to an invasion.

September 11th, 2001: The 9/11 attacks take place, prompting massive policy changes in the government.

18 March 2003: The bombing of Iraq by the combined forces of the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Poland, Spain, Italy, and Denmark began. Unlike the first Gulf War, the Iraq War had no U.N. authorization, and would result in chaos as many competing groups struggled in the power vacuum resulting from the toppling of the government of Iraq.

April 2004: Evidence emerges regarding torture and human rights abuses at the U.S. prison in Abu Ghraib.

June 2004: U.S. hands control of Iraq to an interim government.

2005: A string of bombings, civil unrest, and sectarian violence surrounding the exclusion of Sunni Muslims from the new government causes havoc in Iraq.

December 2006: Saddam Hussein is executed for crimes against humanity.

January 2007: President Bush announces the “surge” strategy, bringing thousands of troops in an attempt to increase security around Baghdad and the “Sunni Triangle” (BBC, 2018).

Conclusion

Both of the wars waged by the United States in Iraq involved massive military logistical movements, political negotiations, and social strife in an atmosphere often hostile to of U.S. military intervention. As with all empires, wars are waged in national self-interest by governing elites with little knowledge of the history of the people they are conquering.

Whether by dropping 88,000 tons of bombs in the Gulf War in 1991, the complete economic blockade of Iraq through 1990s U.N. sanctions, or the disintegration of Iraqi society through eliminating its central institutions during the program of “de-Baathification” in the aftermath of the 2003 invasion, the interventions of the United States in Iraq has left a legacy of civil war, sectarian strife, and the loss of dignity and sovereignty. The United States has left deep rifts and wounds in Iraqi society, manifesting themselves in violent acts of sectarianism, ethnic cleansing, and mass bombings and shootings. The rise of ISIS is probably the greatest indicator of the failure of the “Global War on Terror.”

By choosing to view terrorism through the lens of war, the United States has failed to address the fact that the world order it has constructed has primarily been to the benefit of its own wealth and prosperity, and not that of the rest of the world. Now, in a time of political crises in new and rising nationalisms, the world cannot afford more instability, and Iraq is a continuing testament to the failure of imperial military intervention. Now is the time to answer the call of the millions who protested the Iraq War, to look towards making peace in the world instead of warring to destroy it.

Sources

Ackerman, Spencer. (2010, October 5th). Army Kill Team Member: “We All Said Yes” to Slaying Afghan Civilian. Wired.

Associated Press. (2002, June 30). Fort Lewis troops like their new wheels. Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Associated Press. (2002, December 25). New urban combat training center will be Army’s largest. The Daily News.

Associated Press. (2009, March 5). Army captain charged with stealing $690,000. Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Barber, Mike. (2006, January 4th). Hearing Set for Fort Lewis soldier charged with killing wife. Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Bassett, Russell. (2007, October 6th). Soldiers from the 4th Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division pull security in Rashidiyah, Iraq. Flickr.

BBC News. (2018. October 3rd). Iraq profile – Timeline. BBC News.

Center for Army Lessons Learned. (2004, December 21). Initial Impressions Report: Operations in Mosul, Iraq, Stryker Brigade Combat Team 1, 3rd Brigade, 2nd Infantry. Project on Government Oversight (POGO).

Charlston, Jeffery, & Reardon, Mark. (2007). From Transformation to Combat: The First Stryker Brigade at War. Center of Military History, United States Army.

Collier, Craig A. (2010, September). Now That We’re Leaving Iraq, What Did We Learn? Military Review.

Curtin, Deborah R., & Kemme, Michael R. (1998, August). Final Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) Chemical Quantification at Fort Lewis, WA. US Army Corps of Engineers.

Dawkins, Elisha. (2007, May 3rd). 3rd Stryker Brigade on patrol in Iraq. Department of Defense.

Department of Defense (DOD). (n.d.). M1135 Stryker NBCRV rolling off C-130. Deagle.com.

Albano, Maj. David. (2006, August 5th). 3rd Stryker Brigade begins daily patrols. Defense Visual Information Distribution Service (DVIDS).

Eric Schmitt. (2003, December 28th). THE STRUGGLE FOR IRAQ: THE MILITARY; Quick-Hitting Brigade Test-Drives a New Army Vehicle in Iraq. New York Times.

Frayer, Lauren. (2007, March 15). Insurgents Target Strykers in Iraq. MSNBC.

Global Security. (n.d.). 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division, “Arrowhead Brigade“. Global Security.

Global Security. (n.d.). 4th Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division, “Dragoon Raiders”. Global Security.

Grossman, Zoltan. (2019, January 19). Evergreen class on Nisqually tour of Army base. Facebook.

Jenkins, T. F., Pennington, J. C., Ranney, T. A., Berry Jr, T. E., Miyares, P. H., Walsh, M. E., etc. (2001, July). Characterization of Explosives Contamination at Military Firing Ranges. US Army Corps of Engineers.

Jewish Chronicle. (1958, July). Pro-coup demonstration in Baghdad. Musings on Iraq.

Joint Base Lewis-McChord. (n.d.). 593rd Expeditionary Sustainment Command. Army.mil.

Menzel, Peter. (1991, May). Aerial of burning Al Burgan oil fields in Kuwait after the end of the Gulf War in May of 1991. Peter Menzel Photography.

Metz, Helen Chapin. (1988). The Turkish Petroleum Company. Iraq, A Country Study.

Military.com. (n.d.). M1126 Stryker Combat Vehicle. Military.com.

MyBaseGuide. (2017, March 29). Joint Base Lewis-McChord. MyBaseGuide.

Open-Publishing Newswire. (2004, April 30). Photos of US Torture at the Abu Ghraib Prison in Iraq. Indybay. [CONTENT WARNING: GRAPHIC]

Pepperspray Productions. (2006, August). Indymedia Presents #214, Iraq Veterans Against the War 2006 Press Conference.

The Terrain Analysis Center. (1978, December). Fort Lewis, Washington (including Camp Bonneville, Vancouver Barracks and Yakima Firing Center) Terrain Analysis. US Army Corps of Engineers.

United States Military Academy Department of History. (1991, Feb. 24). History Map of the Gulf War. Emerson Kent.

University of Texas Libraries. (n.d.). Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection. University of Texas.