Katie Dotson

This page focuses on the origins of Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM) and its relationship with the Nisqually Tribe. The Nisqually people have faced hardships since the 1854 Medicine Creek Treaty. They lost most of their reservation land to form the base in 1917 and had brutal encounters with the Army, and with state police in the fish wars of 1960s-70s. Tribal members have been displaced and relocated, and for decades lost their cultural fishing areas, but through constant persistence the tribe has regained part of their land and rights. Their relations with JBLM have improved significantly and they are able to visit ancestral burial grounds. Overall my project will discuss the growth of Camp Lewis to Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

Nisqually Tribal History

The Nisqually Indian Tribe has lived in the Puget Sound watershed for thousands of years. Its original homeland had about two million acres that stretched through what we now call Olympia, Tenino, Dupont, and along the Nisqually River towards Mount Rainier (Nisqually Indian Tribe 2019). Tribal members have always fished for salmon that is the central part of their culture. The Nisqually people lived off their land and the rivers and call themselves the “people of the meadow” after the large Nisqually Prairie in the territory, where they cultivated many roots and edible plants.

Beginning of Displacement and Relocation

In the 1854 Medicine Creek Treaty, Washington Territory Governor (and federal Indian agent) Isaac Stevens severely restricted Nisqually land rights by limiting the tribe to a tiny, rocky reservation next to the Nisqually Estuary, with no access to the river or prairie. The treaty took the rest of their two-million acre territory. Chief Leschi refused to sign this treaty, but it was ratified anyways. He led the resistance in the 1855-56 Puget Sound Indian Wars, securing access to a larger 4,717-acre reservation along the Nisqually River and Nisqually Prairie. Leschi was executed by the territorial government in 1858, but the Army considered him a prisoner of war so it did not participate in his execution.

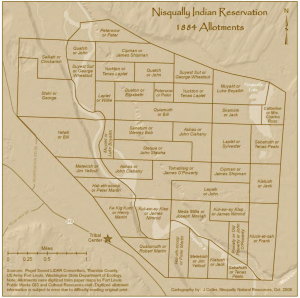

Division of Reservation into Allotments

An allotment is a piece of land deeded by the government to individual Native Americans, as part of the division and privatization of tribally

held communal lands. The entire reservation was divided up under the 1887 Allotment Act. The Act stated that each head of the family would get 160 acres of land on the reservation and each single person would get 80 acres of land. The government would then hold it in trust for 25 years and after those 25 years that tribal member would be granted citizenship and the ownership of the land (NPRA 2019). Whatever land was not allocated to tribal members would be open to non-Indian homesteaders. Despite allotment, the Nisqually were self-sufficient on their reservation, but that came to an end in 1917.

Founding of Camp Lewis

In 1916, a training camp was founded on American Lake by private citizens to encourage civilian readiness, given the ongoing World War I in Europe and clashes with Mexican forces during the Mexican Revolution (see Training and Testing). The Tacoma leaders and Pierce County felt there would be an economic boom if a military camp opened in the area. A committee traveled to Washington D.C. to present the case for the camp, and proposed donating 70,000 acres to the government if it would make the camp a permanent military installation. The Secretary of War selected the site and then Pierce County purchased and donated the land. The 1917 construction of Camp Lewis would be the largest public project since the Panama Canal (Denfiled 2008).

Giving land that was not theirs to give

The problem with Pierce County giving the federal government 70,000 acres of land was that it included 3,353 acres of Nisqually Indian allotments, 70 percent of the reservation, all on the east side of the river. The reservation land was valuable to the Army because it contained the river bottomland and large treeless prairies that would make ideal areas for artillery practice. Pierce County did not plan construction on that part of its land which was not part of the 62,000 acres obtained directly by the federal government. In September 1917, the soldiers trained closer to their constructed base but in October the troops were starting to train on Nisqually land, ruining Nisqually farms.

No choice but to leave

In December 1917, the acting commander of Camp Lewis, General James A. Iron, announced that Camp Lewis needed the Nisqually tribal land for an artillery range because it was “crucial” in the proper training for the new U.S. deployments in Europe. In February 1918, Pierce County started condemnation hearings against Nisqually land owners. What Pierce County failed to recognize was that it had no authority over treaty-reserved lands, because only Congress could condemn them. Pierce County Superior Court Judge W.O. Chapman, who oversaw the condemnation hearings, ruled that precedents made the condemnations legal. The Tribe appraised the land for $93,000 but the county only agreed on $75,000 (Denfield 2008).

With the price already set, the Nisqually tribal members had only two weeks to vacate their land. Those who did not leave their homes in time were forced out by bayonet-armed soldiers in the middle of the night. The soldiers would be less visible at night, and so the Nisqually were caught off guard by the assault. Nisqually landowners did not get their land fairly appraised because Pierce County wanted to stay within its bonded budget. Most Nisqually were not able to find suitable land within the remaining 30% of the reservation with their settlement payments, so they were scattered throughout the state. The United States recognized that the Nisqually were given unfair payments and in 1921 Congress offered $65,000 as compensation for the Nisqually families who lost their land due to Camp Lewis but did that make up for their displacement (Denfield 2008).

Where did the Nisqually go?

There were not many home plots left on the Thurston County (west) side of the reservation that had the kind of land to be beneficial to the Nisqually people. Many tribal members sought refuge with neighboring tribes such as Squaxin Island and Puyallup. C.L. Elis, special supervisor in the Department of Interior’s U.S. Indian Service, reported on the “dispossessed” Nisqually who had to move throughout Washington. Some families, led by Willie Frank and Sallie Jackson found sites near the Nisqually Reservation, but others were not as fortunate. Some were able to live with extended family on other reservations.

Some families moved off reservation land completely. Willie Frank moved to the in-lieu site of Frank’s Landing, on the Nisqually River outside of the reservation. James Nimrod moved to the Skokomish Reservation but grew tired of the river constantly flooding. Lizzie John was at the Puyallup Reservation, and Dewy Leschi moved to the Yakama Reservation (Burgh 2015). While the displaced were able to find new homes on reservations or on non-reservation land, it does not take away the fact that the Army took away their sacred land. The prairie that was home to many tribal members became inaccessible and their sacred burial grounds were off-limits.

From Camp Lewis to Fort Lewis

By 1925, the buildings in Camp Lewis were deteriorating. Military posts around the nation were receiving media coverage for the poor conditions of military posts. The House and Senate were holding hearings on the conditions of military bases, including testimonies on unsafe conditions in the barracks and family houses were. In 1926, a bill was submitted to Congress to fund the construction of new buildings. September 30, 1927 the camp was renamed Fort Lewis because the construction would make it a permanent post (Denfeld 2008). By the start of World War II in 1941 the post had a population of 7,000. With the war waging the Fort began to expand.

The expansion included a permanent hospital in 1944. More people moved in the post with the opening of the hospital, to fill the spaces for medical specialists. During the 1950s two more regimental barracks were built. The base grew tremendously. After each war the Fort would decline in activity, but with each war or conflict new soldiers would come in and new facilities would be built.

Treaty Rights and Tribal Reaccess

During the 1950s-70s Nisqually tribal members pressed to have their fishing rights recognized, as guaranteed in the 1854 Medicine Creek Treaty. The Treaty had promised that no matter if it was on or off the reservation land, tribal members were allowed to fish and hunt in their “usual and accustomed” tribal areas (United States History 2008). For many years, Native people were harassed and arrested for fishing outside their reservations. Finally, because the tribes protested for their treaty rights with “fish-ins,” the federal government stepped in because the State of Washington was ignoring the treaty. One of the stretches of the Nisqually River where they fought for the rights was Frank’s Landing, an in-lieu site for the Frank family, where it had relocated from Fort Lewis. In 1974, Federal Judge George Boldt decided that Washington tribes were entitled to half the salmon and steelhead caught from traditional fishing grounds. Billy Frank Jr., son of Willie Frank, used the recognition of treaty rights as a tool to regain tribal access to Fort Lewis. He went through years of court cases and congressional hearings in order to gain Native access to an ideal site for a fish hatchery inside Fort Lewis.

Clear Creek Fish Hatchery

Billy Frank Jr. and other Nisqually fought very hard to open a fish hatchery on Clear Creek, a small tributary of the Nisqually River. The habitat for the fish was disappearing. Given the presence of both the Alder [Tacoma Power] Dam and the Centralia Dam, the fish were having trouble getting through the watershed and through the poorly functioning fish ladders. In 1977, Billy Frank Jr. proposed a plan to enhance the Nisqually fishery to provide equitable fishing incomes. The tribal plan had three main strategies: “reducing the destructive effects of the Tacoma and Centralia dams; developing a sophisticated tribal fisheries program, including two tribal hatcheries; and reducing the interception of fish bound for the Nisqually River, with priority on treaty negotiations between the United States and Canada” (Wilkinson 2000, 71)

The Nisqually Tribe filed two legal actions against the cities of Tacoma and Centralia. These petitions began in 1975 but they did not end until 1993. Billy attended every proceeding and meetings on this case, to use the proceedings as levers to bring the fish back into the river. The water quality at Clear Creek was perfect for raising fish, especially salmon. Billy was determined to put Clear Creek, Nisqually land inside Fort Lewis, to its best use. He knew the right people who served in high places. He showed Clear Creek to Congressman Norm Dicks and Senator Dan Evans, who made some calls to the Pentagon. “To no one’s surprise, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that Clear Creek was an optimum site for a fish-rearing facility.

By the late 1980s, Congress had authorized funds for an $8.2 million hatchery, one of the largest in the State of Washington. It would operate on 130 acres of military land, leased by the army to the Nisqually Tribe in perpetuity” (Wilkinson 2000, 78). Since the Clear Creek Hatchery opened in 1991, the numbers of returning fish have exceeded expectations. The hatchery began to improve relations between the Tribe and Army and has opened a more respectable relationship. The Army recognized that the lands confiscated in 1917 are still legally part of the reservation, so the Tribe could reacquire them if the base ever closed.

In 2005, the Base Realignment Commission “directed that Fort Lewis and the adjacent McChord Air Force Base merge. The merger was part of a nationwide movement toward joint basing, the culmination of an effort beginning in the mid-1980s to unify the separate military services and bring about more effective inter-service operations. On October 1, 2010, Fort Lewis and McChord Air Force Base became Joint Base Lewis-McChord or JBLM” (Denfeld 2008).

Leschi-Quiemuth Honor Walk

The Leschi-Quiemuth Honor Walk is an annual event that the Army, has allowed since 2008, for tribal access to cultural sites inside the base. The Army actually shuts down training during this time. It is a 7.2-mile or 2.5-mile walk, or a 12.5-mile run or bus tour that visits the land and graves of tribal ancestors (Sadler). The tour starts at Kul-kul-eh Outstation or Back Squally Plain, a farm in the 1830s that produced oats, barley, potatoes and pasturage for horses, and where Leschi and his brother Quiemuth tended to their horses. From there the walk/run goes to Yll-whaltz, a Nisqually winter village and also different allotments of tribal families. Walkers visit four cemeteries and the walk ends at Clear Creek Hatchery.

By ending at the hatchery the walk is symbolizing the successes of the tribe. Although tribal members were forced from their land they are able to have a piece of it to continue their heritage throughfishing, hunting, and gathering. The Honor Walk is an emotional event because tribal members who lost their territory are able to come back to their ancestors’ homesteads and cemeteries. The walk is named after Chief Leschi and his brother Quiemuth, who were both killed in their struggle for tribal sovereignty and treaty rights (Nisqually Indian Tribe & U.S. Army, 2017).

Conclusion

The Nisqually Tribe has faced decades of grief and displacement. Chief Leschi and his brother Quiemuth fought for their land and, although they were murdered in the process, they successfully won a larger reservation than the government promised in the treaty. But in the name of expanding the military presence in the state, most of that larger reservation was seized for Fort Lewis, in an example of “ethnic cleansing” that was and remains shameful.

Nisqually tribal members were forced to leave their land and find a new home on the part of the reservation that remained, or had to leave the area. They have continued to feel grief when they were harassed for fishing in their ancestral tribal grounds. The Nisqually people fought to regain their treaty rights, and to reaccess their stolen lands on the military base. They are not able to access the base as much as they should but there are steps in the right direction, such as the Clear Creek Fish Hatchery and the Honor Walk.

Sources

Alaska Native News. (2014, June 29). Chapter Fifteen | Clear Creek Hatchery. Alaska Native News.

Banel, F. (2015, July 10). The forgotten early history of Joint Base Lewis-McChord. MYNorthwest.

Bergh, E. (2015, October 08). History: Nisqually People Were ‘Widely Scattered’. Nisqually Valley News.

Burns, Carol. (1971). As Long as the Rivers Run (Documentary).

Denfeld, D. (2008, January 16). Fort Lewis, Part 1: 1917-1927. HistoryLink.

Denfeld, D. (2008, January 16). Fort Lewis, Part 2: 1927-2010. HistoryLink.

Denfield, D. (2011, August 18). Fort Lewis and McChord Air Force Base merge to create Joint Base Lewis-McChord. HistoryLink.

Hensin, C. (2016, May 17). Nisqually tribe walks for remembrance. The Pioneer.

Indian Tribe, N. (2019). Heritage. Nisqually Indian Tribe.

Kluger, Richard. (2011). The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek: A Tragic Clash Between White and Native America. New York: Vintage.

NPRA. (n.d.). History and Culture: Allotment Act -1887. Northern Plains Reservation Aid.

Nisqually Indian Tribe and U.S. Army. (2017, May 6). The Annual Leschi-Quiemuth Honor Walk Tour Booklet. Nisqually Reservation, Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

Nisqually Indian Tribe. (n.d.). Nisqually Indian Tribe. United States History.

The Nisqually People. (2010, May 8). The Dispossessed: The Condemnation of the Nisqually Reservation. Yelm History Project.

NPAIHB. (n.d.). Nisqually Tribe. Indian Leadership for Indian Health.

Peterson, D. (2018, April 22). The Deep Wisdom of the Elders. Tribal College.

Smith, J. (2013, May 9). The Long Walk Home. Northwest Guardian.

Wilkinson, Charles. (2000). Messages from Frank’s Landing: A Story of Salmon, Treaties, and the Indian Way. Seattle: University of Washington Press.