Lincoln Koester

The Vietnam War was a conflictive, turbulent, and extremely controversial era in U.S history. Fort Lewis and the Pacific Northwest reacted to the Vietnam War in a variety of ways. For example as troops from Fort Lewis preparing to fight Communist forces in Southeast Asia, some troops from the same base were ready to oppose their government’s policies by joining the antiwar movement.

From May 1966 to June 1972, Fort Lewis trained 302,000 soldiers and deployed them overseas, mostly to Vietnam. At the same time, the strong antiwar movement had reached Fort Lewis and the area became known for its G.I coffeehouse, the Shelter Half. This helped orchestrate a social network of civilians and soldiers within the antiwar community, much like on other military bases around the world (Cortright 2005; Zeiger 2005). Underground newspapers on base created a platform for G.I.s opposing the war to voice their disapproval of the war.

Preparation and Financial Cost

“In the years just prior to the war in Vietnam and decades before the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Fort Lewis and Washington state were home to the Army’s first large-scale experiments in counterinsurgency warfare. Between 1962 and 1965 the Army used Fort Lewis-based units to conduct a series a counterinsurgency-focused exercises to develop and validate the nation’s embryonic doctrine for fighting the Cold War’s numerous “wars of liberation” (Flint 2017).

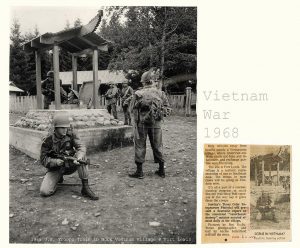

Infantry troops at Fort Lewis underwent eight weeks of basic training in addition to a ninth week highlighting the type of warfare to be expected in Vietnam before deployment.

To get a sense of combat in Vietnam, mock villages that included tunnel systems were constructed to replicate the elements of jungle and guerrilla warfare (Flint 2017). (See Fort Lewis Testing and Training)

Renovating and preparing Fort Lewis for the war effort costed more than 3.5 million dollars. These funds went toward refurbishing and constructing classrooms, ranges, and barracks, which made Fort Lewis an effective training facility, graduating up to 1,100 troops a month (Flint 2017).

Vietnam Deployments

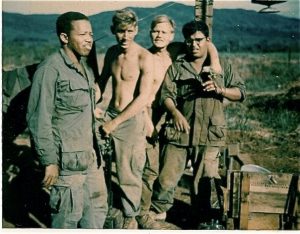

From May, 1966 to June, 1972, Fort Lewis trained 302,000 soldiers and deployed them overseas, including the 4th and 9th Divisions. Many of these troops experienced their fair share of violence and trauma when deployed Vietnam, much like the other half-million American soldiers in the war.

9th Infantry Division

“The 9th was the only U.S. Army combat division reactivated specifically for service in Vietnam. Mobilized at Fort Riley, Kansas, in 1966, the division was trained, equipped and organized to serve with the Mobile Riverine Force, a joint Army-Navy amphibious force deployed to South Vietnam’s harsh Mekong Delta region” (Flint 2017).

During their entire tour in Vietnam, the 9th Infantry Division from Fort Lewis killed 1,869 enemy soldiers, though “body counts” were notoriously unreliable. (HistoryLink.org)

4th Infantry Division

“The 4th Infantry Division deployed from Fort Lewis to Camp Holloway, Pleiku, Vietnam on September 25, 1966 and served more than four years, returning to Fort Carson, Colorado on December 8, 1970. Two brigades operated in the Central Highlands/II Corps Zone, but its 3rd Brigade, including the division’s armor battalion, was sent to Tay Ninh Province northwest of Saigon to take part in Operation Attleboro (September to November, 1966), and later Operation Junction City (February to May, 1967), both in War Zone C.

Throughout its service in Vietnam the Ivy Division conducted combat operations in the western Central Highlands along the border between Cambodia and Vietnam. The 4th Infantry Division experienced intense combat against NVA regular forces in the mountains surrounding Kontum in the autumn of 1967. The division’s 3rd Brigade was withdrawn from Vietnam in April, 1970 and deactivated at Fort Lewis. In May the remainder of the division conducted cross-border operations during the Cambodian Incursion. The Ivy Division returned from Vietnam in December and was rejoined in Fort Carson by its former 3rd Brigade from Hawaii, where it had re-deployed as part of the withdrawal of the 25th Infantry Division. One battalion remained in Vietnam as a separate organization until January, 1972. During the four and a half years of combat operations during the Vietnam War, 2,531 Ivy Division soldiers were killed in action and another 15,229 were wounded. After Vietnam the Division settled at Fort Carson, Colorado where it reorganized as a mechanized infantry division” (The Ivy Division 2008).

David Maraniss’s book They Marched Into Sunlight: War and Peace Vietnam and America, October 1967 by , describes the experience of a subdivision called “C Packet” that deployed from Fort Lewis. The mood preceding their arrival was tense and eerie. “Lieutenant Grady said he never saw so many drunk kids in his life, almost every single one dead drunk…Just get these kids back in, Grady said. They know where they’re going. Let’s not make this any tougher than it is.” ( Maraniss 2004, 12)

Once C-Packet arrived in Vietnam, it was absorbed into Delta Company, a subdivision of a regiment called the Black Lions. The men from Fort Lewis were now part of a cluster of soldiers under the command of an authority that was more concerned with winning a war than preserving the troops’ lives. This is apparent because according to Maraniss, one colonel refused to share his “facts of life in the war zone” with the new troops and claimed “Enlisted men could not be trusted, he said. Enlisted men were nothing but sons of b—-s” (Maraniss 2004, 17).

Antiwar movement involvement

“Soldiers, sailors, airmen, and veterans turned against the war in Vietnam in large numbers, and by 1971, the military was, by its own admission, unable to fight the war in Vietnam because their soldiers would not obey” (Kindig 2008).

The antiwar movement had a strong presence around Fort Lewis, and assisted soldiers in opening the Shelter Half in 1968. It was one of the many G.I coffeehouses that sprung up near bases, so soldiers could express opinions and their disdain for the war, without worry of being reprimanded.

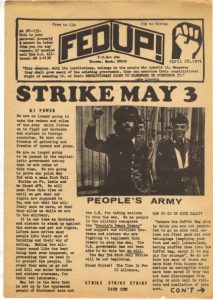

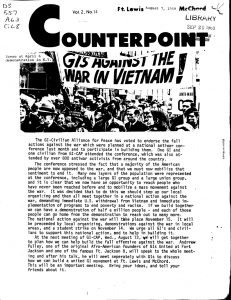

With the emergence of these coffeehouses came G.I newspapers such as Counterpoint, Fed Up!, and the Fort Lewis-McChord Free Press that brought light to the hardships that were endured by soldiers and their families in hopes that the movement would spread throughout the nation. In 1968, the G.I.s stationed at Fort Lewis even collaborated with students from the University of Washington and organized protests in Seattle (Kindig 2008).

|

|

Conclusion

The Vietnam Era left its mark on the Pacific Northwest by costing the region not only millions of dollars but also the lives of thousands of young men. These costs led to the opposition of the war which was orchestrated by civilians and G.I’s working together to bring the violence in Vietnam to an end.

Sources

Bryson, J. (n.d.). [Army G.I.s opposed to the Vietnam War at the Shelter Half Coffeehouse in Tacoma, Wash., in 1969.] New York Times.

Coffman, N. (2016, March 10). The U.S. Army 4th Infantry Division in Vietnam. Newsrep.

Cortright, David. (2005). Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Denfeld, D. C. (2011, December 28). HistoryLink.org.

Flint, E. W. (2017, March 23). Fighting the Cold War. JBLM Northwest Guardian.

Flint, E. W. (2017, February 23). Vietnam tours began here. JBLM Northwest Guardian.

Flint, E. (2017, April 20). Fort Lewis major training hub for Vietnam. JBLM Northwest Guardian.

Flint, E.W (2017, August 10). ‘Old Reliables’ served at Fort Lewis from 1972-1991. JBLM Northwest Guardian.

Flint, E.W. (2017, August 22). History of 9th Division at JBLM. JBLM Northwest Guardian.

HistoryLink.org. (2012, December 27).

Kindig, J. (n.d.). GI Movement: Antiwar Soldiers at Fort Lewis, 1965-1973. University of Washington.

Kindig, J. (2008). GI Movement: Underground Newspapers. University of Washington.

Lonidier, F. (n.d.). Antiwar veterans protest at the Federal Building in Seattle, September 1968. New York Times.

Lonidier, F. (n.d.). SP4 Haines with an M-60 machine gun. Notice the defoliation of the surrounding area caused by Agent Orange and napalm. Mount Holyoke College.

Lott, G. (2018, August 9). Vietnam 50th Anniversary Commemoration Aug. 11. Northwest Military.

Maraniss, D. (2004). They Marched Into Sunlight: War and Peace, Vietnam and America, October 1967. New York: Simon & Schuster.

“The Ivy Division”. (2008). Military Vet Shop.

Vietnam, 1966-1972. (2015, July 21). Lewis Army Museum.

Zeiger, David. (2005). Sir! No Sir!: The Suppressed Story of the GI Movement to end the War in Vietnam [documentary]. Displaced Films.