Eric Meyer

In September 2018, Joint Base Lewis-McChord’s public army museum completed a $3 million, 4,000-square-foot renovation, one which came just after a $9.6 million renovation completed in 2012 (Tacoma Weekly 2018). JBLM’s free public events, such as its annual Freedom Fest, draw thousands of attendees and feature live music, carnival rides, car shows, and hands-on tours of military equipment. JBLM’s Public Affairs Office also ran a print newspaper, the NW Guardian, until 2018, when it moved its promotions and original news articles online. On the whole, JBLM puts quite a few resources into its public relations efforts.

Indeed, most local residents of Pierce and Thurston counties are likely familiar with these P.R. efforts, having recognized the Lewis Army Museum countless times while driving on I-5, or seen JBLM’s newspaper or magazine propped up on newsstands, or heard of or attended one of JBLM’s public events. Because of this familiarity, most have likely never seriously thought to ask: why? Why does a military base spend so much money on a museum, and what purpose does that museum serve to them, exactly? Why does the base put so many resources into hosting massive community events on-base? Who are JBLM’s magazines and social media posts written for, and for what reason? This webpage will seek explore these questions, with a particular focus on JBLM’s Lewis Army Museum.

Lewis Army Museum

A Brief History and Description

The only certified U.S. Army museum on the West Coast, JBLM’s Lewis Army Museum resides within an appropriately historic building, the former Red Shield Inn. Constructed in 1918 by the Salvation Army, the building was used to house soldiers and their families serving at Camp Lewis during World War I. The building functioned as an Army hotel and apartment complex until 1972, when more modern housing developments rendered it obsolete and allowed the newly founded Lewis Army Museum to take up its residence (Lewis Army Museum 2019).

Two recent multimillion dollar renovation projects, the first in 2009-12 and the second in 2016-18, have sought both to modernize the museum and recreate the feel of the building’s historic roots. The museum’s lobby is meant to look and feel like that of the old Red Shield Inn, and visitors are greeted by hardwood floors, an antique piano, a brick fireplace, and a leather-bound guest book. Unlike a hotel, however, visitors’ temporary stay at the museum is completely free, and its location on a military base necessitates a uniformed escort past a locked gate from the parking lot to the museum.

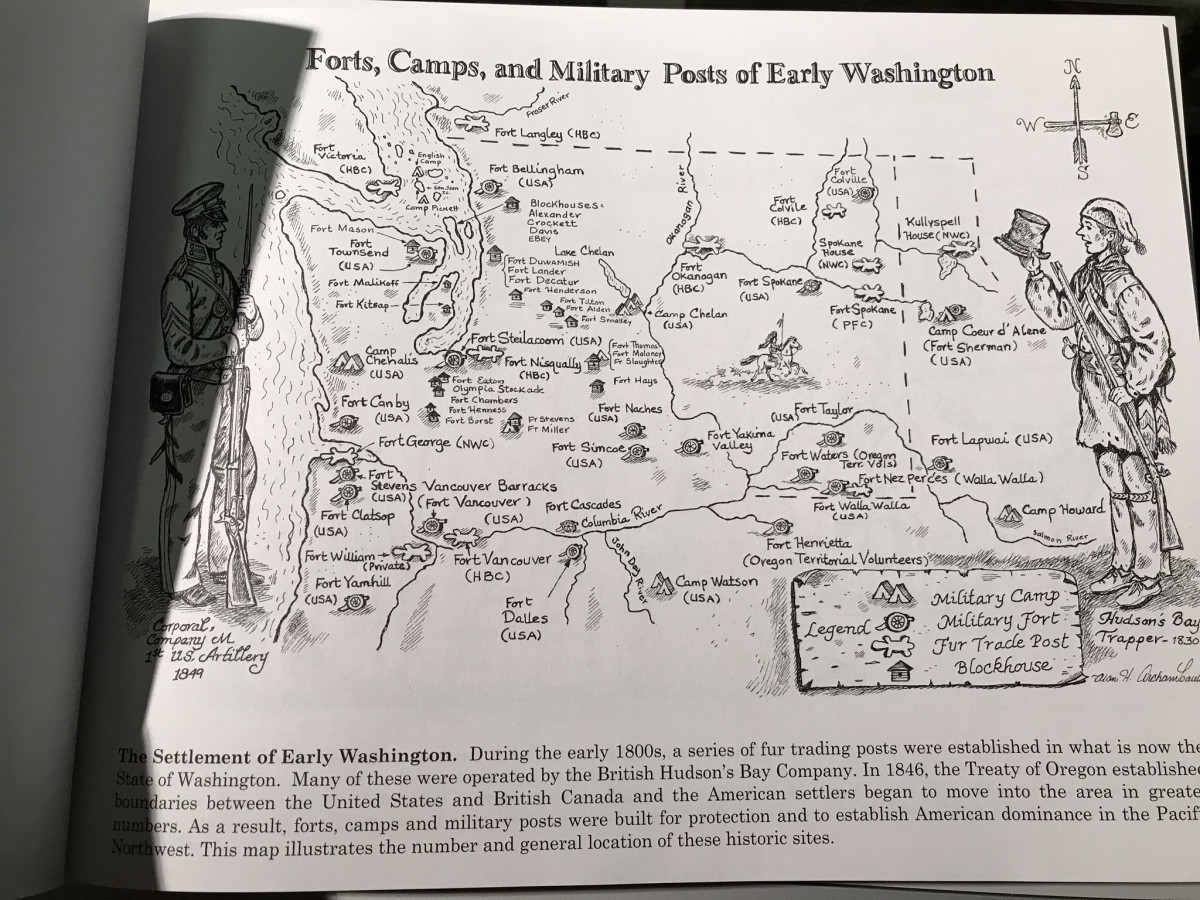

The museum itself is divided into three main exhibits: the vehicle lot, the Lewis Gallery, and the Hall of Valor. The vehicle lot covers the museum grounds, and features historical tanks, artillery equipment, troop transport vehicles, and missiles, on which more information is dependent on a free docent-led tour, since no plaques accompany the vehicles. The Lewis Gallery tells the Army history of JBLM, from the journey of its namesake explorer Captain Meriwether Lewis, to the founding of Camp Lewis, all the way up to the 2010 merger of Fort Lewis and McChord Air Force Base into JBLM, and its role in Iraq and the “Global War on Terror.”

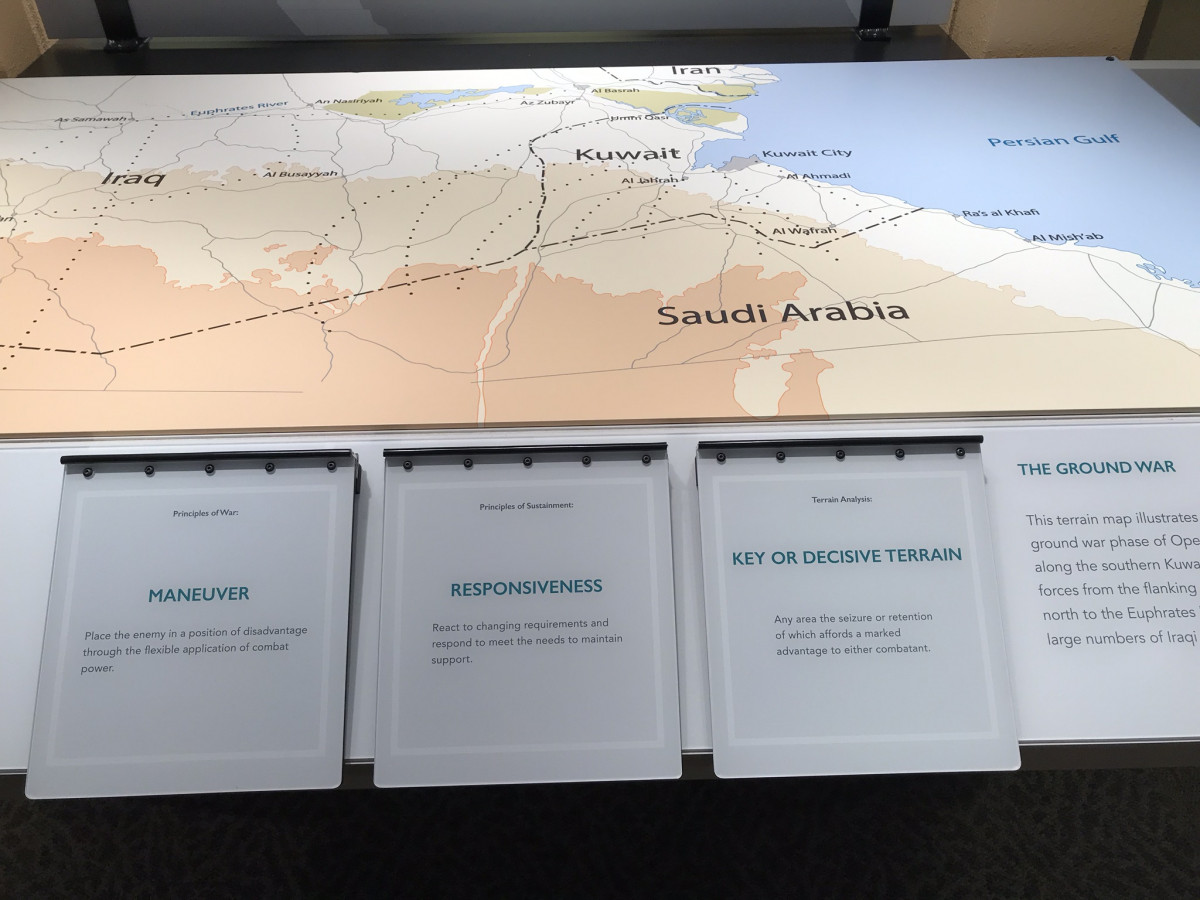

Whereas the Lewis Gallery focuses on the changing experiences of Army soldiers who trained for various wars at JBLM, the Hall of Valor focuses more on the wars and battles themselves. Its exhibits feature the equipment used by soldiers during ten select battles waged by JBLM-trained troops, and each battle exhibit is used to illustrate one ‘principle of war,’ one ‘principle of sustainment,’ and one example of ‘terrain analysis’ through interactive maps.

To What End?: An Interview with Director Erik Flint

So what is the purpose, and the goal, of such a museum? Overall, the museum displays tended to avoid details of politics and depictions of fighting and violence, choosing instead to emphasize physical facts, figures, and abstract combat strategies. The displays that sought to explain the political situations surrounding JBLM’s history and the wars it supported were kept very brief, and were often worded in ways which shied away from confronting some of history’s harsher realities. For example, the display describing how Camp Lewis obtained its land from the Nisqually Reservation – a somewhat ugly part of the base’s history – is told in a way that forgoes the unpleasant details, instead stating in a passive voice that “arrangements were made to ‘borrow’ the land until negotiations were complete.”

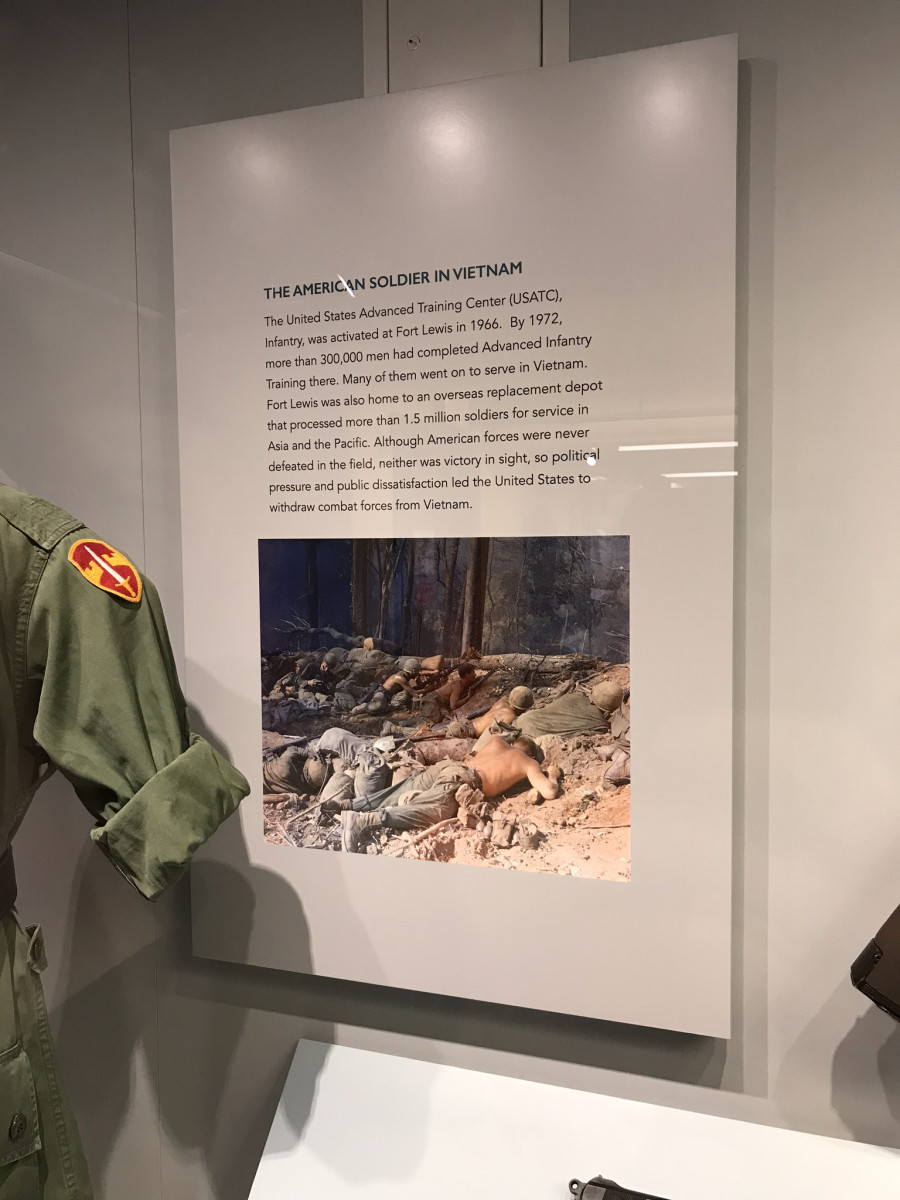

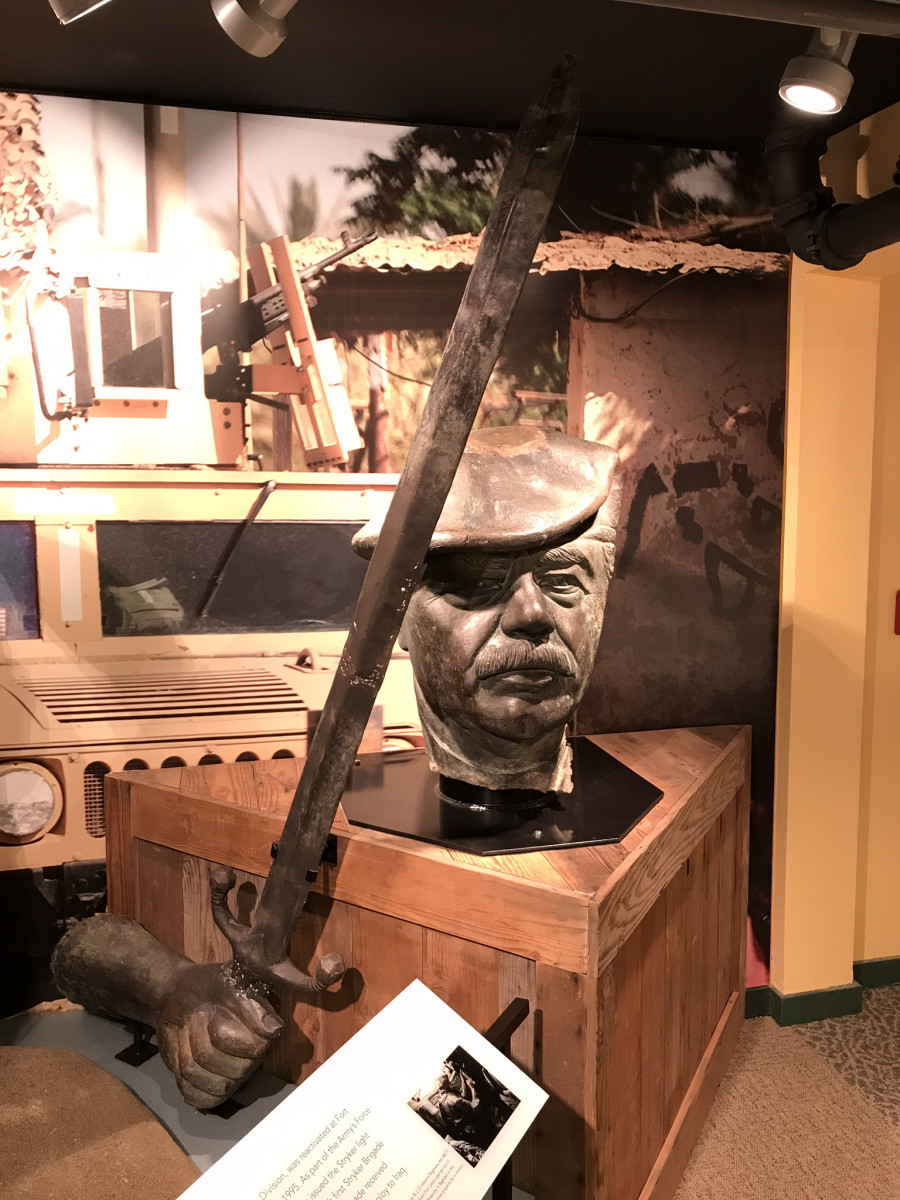

Another display on the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam qualifies “neither was victory in sight” with the claim that “American forces were never defeated in the field.” However, the museum’s more neutral tone also extends the other direction, and the displays do not overtly glorify the Army’s history. A giant metal bust of Saddam Hussein that was taken from Iraq, for example, is tucked away in a far corner of the Hall of Valor, far from being a boastful centerpiece of patriotism and victory. The purposes and goals of the museum were not readily apparent to me on my visits, so I set up an interview with Erik Flint, the Lewis Army Museum’s director since 2015, to discuss this question.

According to Flint, the primary purpose of the museum actually has to do with military training: “The number one mission really is to train better soldiers. The Army looks at us and says, ‘we collect all this stuff, we display all this stuff, we have all these museums – what do they do for the Army?’ The Army’s job to be ready to go fight.” To this end, the museum’s recent extensive renovations were partly focused around the education of soldiers. The new Hall of Valor is centered on the illustration of various ‘principles of war’ for this very reason – “The ultimate intent is that it becomes tied in with the Army professional education system.” By extension, the museum also hopes to instill in this internal target audience a certain pride in the Army’s history: “Also we’re here for unit pride… And that’s a big piece of military service, is how you feel about your organization. It’s like how people are proud of their football team.”

Although training soldiers is the museum’s official primary purpose, “…it by no means takes up the majority of our time, because concurrent with that is education and outreach.” The museum puts great importance on “telling the Army story” to the general public. According to Flint, this past year (2018) the museum saw over 23,000 visitors – about 1,000 of whom were K-12 students on school trips. Flint said that currently the majority of civilian visitors have some kind of prior connection to the military; many are veterans looking to tell their own stories to family or friends. However, the museum places great importance on expanding past their current military-connected audience: “We’re trying to reach beyond that, to directly engage the average member of the community and of the public… We want to support those typical constituents that come in, who typically have a military connection of some kind. But we really want to reach out to people who didn’t know they wanted to learn about the Army.”

The museum has worked hard to achieve this goal, setting up promotional booths at various local events, sending representatives to arts and teacher conferences, and attempting to eliminate many of the hoops civilians had to jump through to gain access to the on-base museum. This coming year, the museum will be hiring a third full-time employee whose primary focus will be reaching out specifically to educators and schools, advertising the museum’s free admission as an incentive to bring more school groups on tours. Overall, while 23,000 visitors and 1,000 students on tour annually may sound like a lot, Flint is unhappy with the numbers, yet optimistic that they can improve: “Based on the size of our museum and our population base… we have not reached our potential. Part of that is we’ve been closed for various reasons for four out of the last eight years… and we are on track to exceed that number [23,000] this next year [2019]. So we’re continuing to grow.”

So why is it so important for the museum, and by extension JBLM, to increase visitation numbers and educate people not previously connected to the military, such as schoolchildren? For Flint, the fundamental goal is to “Tell the Army story” in service of “…creating advocates amongst the American public for their Army.” While Flint said that he is always cautious about crossing the line of whitewashing and propaganda, ultimately, “I have a perspective from a federal Army museum: I want to tell as positive a story as possible,” while “…showing the Army story as honestly and truthfully as we can given the resources that we have.” While the museum does not avoid teaching its soldiers about the unpleasant parts of Army history when appropriate for their training, and anyone seeking out information would get all that the museum has, Flint said the museum would never have a display on something like the My Lai Massacre. It is simply too graphic for the children who so commonly visit, and many other historical issues are still too current to be objectively covered as a history museum.

But Flint brought up other areas in which the museum consciously does shed light on its often less-than-ideal past, and how in doing so he hopes to further the goal of ‘creating advocates for their Army’. As Flint explained,

“If you look through our mannequins that we have, going from 1900 up to 2006, you essentially see: white guy, white guy, white guy, white guy, white guy, and then suddenly you start to get women, different ethnicities, and that was very deliberate. There’s a reason when you walk in the museum that you see a man in an original World War I uniform on the left, and then we have a female mannequin in the latest combat equipment [on the right]. The fact that it’s a female is a conscious idea to go, ‘the Army’s very different.’”

This demonstration of how the demographics of the Army have changed was important for Flint in that it serves to help break stereotypes of the Army that the general population might hold surrounding inclusivity and equality. Flint also hopes it emphasizes the extent of the Army’s improvements by putting them in historical context.

This is all understandable, but there was one historical omission I had noticed in the museum’s displays that I still did not understand. Given the museum’s mission of showing the Army’s improvements by putting them in context, why not include things like the somewhat ugly historical relationship between Fort Lewis and the Nisqually Tribe? Such a display could be an ideal way of publicizing the relatively – even uniquely – positive and cooperative relationship that JBLM now has with the Nisqually, framing the Army’s progress in that area just as the mannequins frame their progress in the realm of social representation. Additionally, the way the base forcibly obtained its land from the Nisqually is not obscenely gruesome like the My Lai Massacre, nor is it too current to be appropriately covered in a history museum. So why not? Despite asking this question as tactfully as I could in multiple ways, I did not get a real answer from Flint.

Perhaps the issue is left out for the matter of ‘unit pride,’ or for the veterans who visit looking to tell their own personal tales of nostalgia and hardship. After all, this history of the Nisqually has very little to do with the goal of ‘training better soldiers.’ Or, perhaps it is that such an exhibit would not be so beneficial to the cause of “creating advocates amongst the American public for their Army” after all.

According to Flint, the museum’s current approach is to that of, “Here are the tools, here’s what happened, it’s up to your interpretation, do you wish to explore it more?” However, the topics which visitors are stimulated to learn more about are naturally going to be determined by what the museum does or does not include in the first place. It is possible that the museum is concerned with keeping current issues off the mind of the public. Even if the Army is framed positively through its progress with the Nisqually, such an exhibit might also encourage visitors to look up what the current issues with the Nisqually may be. For all the progress the Army has made in that area, there are indeed still issues and points of contention. On that note, even Flint’s mannequin example is only an implicit acknowledgement of the Army’s not-so-pleasant past. There are no plaques or overt exhibits on the matter, and so it is unlikely that a visitor would be spurred to wonder about the current issues the Army faces with social equality. To do otherwise might be to jeopardize the goal of creating ‘advocates for their Army’ – and risk creating advocates critiquing the Army instead.

There seem to be two parallel target audiences that the Lewis Army Museum wants to cater towards. There is the internal audience, made up of soldiers training at the base and veteran visitors; and the external audience, made up of the general public not already connected to the Army, such as schoolchildren. In some sense, these two target audiences create conflicts in the museum’s goals and approaches. The Hall of Valor’s focus on ‘principles of war’ to train soldiers, for example, is somewhat at odds with the kind of exhibit which would engage and inspire children, or adults not previously connected to the Army. The museum is making an effort to bridge such gaps, and Flint told me that he is in the process of “…developing syllabi for different age groups and different organizations.” However, in a much larger sense the museum’s two target audiences present the same goal, and the same challenge. Whether it be in service of establishing unit pride or creating advocates for the Army amongst the general public, the museum’s objective is to portray the Army in as positive a light as possible.

JBLM’s Public Events

Every year, Joint Base Lewis-McChord hosts two large on-base events, both free to the public. JBLM’s Armed Forces Day is held in late May as part of a larger national celebration of the military (Tacoma News Tribune 2017), while JBLM’s Freedom Fest is held in observation of the 4th of July. Besides Freedom Fest featuring a car show and fireworks (JBLM Public Affairs Office 2018), both events are extremely similar, and so for the purposes of this webpage I will be focusing on just one, Armed Forces Day.

Approximately 15,000 people attended the 2018 Armed Forces Day, enjoying a grand convergence of military hardware and fairground festivities (Mayhugh 2018). The event featured live music and local food vendors across the field from reenactments of historical battles and live cannon fire. Families were treated to gyrating thrill rides and lighthearted carnival games, as well as soldier-guided tours of real military vehicles such as Stryker armored vehicles and Apache helicopters. Children enjoyed holding mounted machine guns and high caliber sniper rifles (Ofamen 2018), before getting their face painted in camo in preparation for laser tag or foam sword fighting. Artillery equipment and magicians competed for attention, while bouncy houses shared space with an arrangement of military fighter jets. All of this, “…to celebrate and honor the military and to serve as an educational program of sorts for the civilian community by expanding the public’s understanding of the military” (Tacoma News Tribune 2017) – a sentiment very similar to that of the Lewis Army Museum’s goals.

But why have military vehicles and weapons, which are fundamentally tied with destruction and death, alongside carnival rides and bouncy castles? Perhaps the carnival activities are simply to attract people into a space where they will gain a greater understanding of the military – but then, why do people need to become familiarized with the military through the weapons of JBLM? And a familiarity with weapons does seem to be the kind of ‘understanding’ events such as Freedom Fest and Armed Forces Day are attempting to impart. They do not have analysts or strategists or academics speaking about the bureaucracy, politics, or ethics of the military. This may seem like a no-brainer – of course they don’t! But that does not answer the question of ‘why not?’ or the question of why the events do focus so much on military equipment. The very fact that it seems obvious what the military focuses on at these events only makes it even more interesting for inquiry.

A Possible Explanation

I do not have the final answer to why JBLM’s community events are what they are, just as I do not have the final answer to why the Lewis Army Museum does not include more on their relationship with the Nisqually. However, the emphasis on military equipment over all other types of understanding of the military, paired with the equipment’s confluence with carnival activities and a festive atmosphere, evokes what militarization academics such as Catherine Lutz and Noenoe Silva have observed on the topic of military “normalization.” In writing about the reasons why the United States’s overseas bases are tolerated, especially in the face of regular environmental and crime controversies, Lutz concluded that one of the main factors is normalization: “…bases are naturalized and normalized, meaning that they are thought of as unremarkable, inevitable, and legitimate” (Lutz 2009). Noenoe Silva, in an analysis of why a highly militarized place such Hawai’i sees little opposition to the military, said, “There’s so much military here – I don’t mean just that there’s military presence on the islands, but that we’ve become so used to it. People in Hawai’i don’t even notice it. There’s an encroachment of military thinking that seeps into our everyday lives here in Hawai’i. And then it becomes normalized” (Kelly 2008).

In inviting the general public to tour military vehicles and pose with assault rifles, it is possible that JBLM wishes to familiarize – and thus normalize – its local presence, a presence which has come under some scrutiny through its history, including in recent years. Whether intentional or not, the equipment’s pairing with carnival rides and a festive atmosphere might complement this effect of normalization, serving to instill associations of fun and community with the weapons, rather than those of destruction and death. And just like the Lewis Army Museum, while the Army could make itself look good by bringing up topics of politics and ethics, such subjects are fundamentally risky if one’s goal is to not just ‘expand the public’s understanding of the military’ but also to expand their understanding in a positive way. In short, it seems likely that the events’ purpose is at least partly the same as the Lewis Army Museum’s goal “to create advocates among the American public for their Army” – or at least, to prevent the public from advocating against them.

JBLM’s Print and Social Media

The JBLM Magazine, the JBLM Northwest Guardian newspaper, and the Fort Lewis Ranger newspaper are all familiar staples of newsstands in the South Puget Sound area, and JBLM regularly posts on its own Facebook and Twitter pages. Just as with the Lewis Army Museum and JBLM’s public events, I tried to find out who all this public relations effort is for, and for what purpose it exists.

In scouring headlines and reading countless articles from the Northwest Guardian newspaper, the JBLM Magazine, and the base’s social media accounts, it became apparent that these media outlets are almost exclusively targeted at an internal audience, unlike JBLM’s museum and public events. Almost every article or post is about an on-base program or event which would be irrelevant to the general public, such as advertisements for military spouse career events, on-base road closure warnings, and announcements about the grand opening of a new on-base Arby’s. Other articles are similarly oriented, usually serving to set examples for what a ‘good’ military spouse or ‘good’ soldier looks like, such as one about soldiers volunteering to clean up a local school (Schroeder 2015), or one titled “JBLM Army wife supportive, volunteers for anything” (Kingsland 2018).

As for the JBLM Magazine and the Fort Lewis Ranger, the two are actually not affiliated with the base at all, and are instead privately owned and independently operated ventures looking to profit from the local news demand of military families (De Paul 2017). The Northwest Guardian, meanwhile, actually ended its operations in June 2018 after 28 years in print, citing diminishing readership in an increasingly digital world (Piek 2018). JBLM has since moved all of its news articles to its Facebook and Twitter pages, but posts on the sites rarely garner more than twenty ‘likes’ or a handful of ‘retweets.’ In all, JBLM’s print and social media activities pale in comparison to their museum and public events, and from their internal target audience they can hardly be said to be a true public relations effort.

Conclusion

So why does JBLM put so many resources into its museum, public events, and media platforms? The base’s print and social media output makes answering this question in that realm relatively straightforward. Its articles and posts are to keep its soldiers and their families informed about on-base news, as well as occasionally promote positive behaviors such as volunteer work. The purposes of the Lewis Army Museum and events such as Armed Forces Day, on the other hand, appear more complicated, but in sum both seem to have the goal of portraying the base and the Army in a positive light while avoiding the Army’s controversies and potentially problematic subjects. In doing so, the Lewis Army Museum hopes to ‘create advocates’ for the Army amongst people with no prior connection to the military, while it seems as though JBLM’s events hope to normalize militarization by ‘creating a better understanding of the military’ through positive exposure to military equipment and weapons.

In essence, both of these goals may be rooted in the geographical concepts of ‘Space’ and ‘Place.’ In geography, a ‘Space’ is a location or landscape that is devoid of personal meaning or significance: a typical strip mall intersection, or the twentieth of 200 corn fields someone might drive past on a road trip. A ‘Place,’ on the other hand, is a location that holds meaning and significance for the observer, whether positive or negative: the cemetery where one’s grandparents are buried, or the overlook where one was proposed to. In the absence of any public relations efforts on the part of of the base, JBLM would be a ‘Space’ for most locals – somewhere initially devoid of meaning. Unlike a random cornfield, however, a place like JBLM cannot remain a Space for long, and locals would be left to fill in the gap of meaning with their own associations – some of which might be full of suspicion or mistrust, whether for political, social, or environmental reasons. Instead, public relations effort such as the Lewis Army Museum and Armed Forces Day are opportunities for JBLM to take more control over the Place-making interpretations and associations that the general public develop. Museum visitors learn about the brave adventures of Lewis and Clark rather than the Army’s forcible acquisition of Nisqually Reservation land, and event attendees come to associate guns and artillery with jugglers and bouncy houses rather than war and suffering.

It is important to recognize, however, that while JBLM’s public relations efforts might have questionable – if understandable – motives, they do provide many real public goods regardless. Many of the on-base activities and resources that JBLM’s Facebook and Twitter posts promote are genuinely useful services or positive events, from tax filing assistance to on-base community bowling events. In fact, the number of community services and amenities led retired General Wesley Clark to ironically refer to the system as “…the purest application of socialism there is… It’s a really fair system, and a lot of thought has been put into it, and people respond to it really well” (Vine 2017). The base’s social media posts help get more people involved in these services and in their community.

For all that the Lewis Army Museum may leave out in its exhibits, it is still a true museum run by professional historians, and the museum represents a genuinely useful resource for students and researchers looking to learn about and analyze military history. A key part of the recent renovations was, in fact, a new research room to make the museum more accessible for student projects (Craker 2015). As Erik Flint said, anyone coming in seeking information will get all that the museum has – even the not-so-pleasant bits. Meanwhile, events such as Freedom Fest and Armed Forces Day do provide a real place for people in the community to get together and have fun, spending quality time with their family and friends – and for free! Even if the effects or intentions of the events might be to normalize militarization, the positive experiences that such events engender are still real, and cannot be denied. These are free public resources and positive experiences which would not exist without the military-funded public relations efforts of Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

Sources

2018 Freedom Fest – Online Interactive Guides. Weekly Volcano, (n.d.).

Craker, V. S. (2015, December 15). New direction for Lewis Army Museum. Army.com.

De Paul, J. (2017, January 20). Ranger newspaper celebrates 66 years Northwest Military.

Desk, N. (2018, September 13). Fort Lewis Museum Opening New ‘Hall of Valor’ Gallery. Patch.

JBLM Public Affairs Office. (2018, July 2). JBLM to host two day July 4th Freedom Fest Celebration.

Kingsland, R. (2018, April 12). JBLM Army wife supportive, volunteers for anything. Northwest Guardian.

Lewis Army Museum. (n.d.). Brochure.

Lutz, C. (2009). The Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle Against U.S. Military Posts. New York: New York University Press.

Mayhugh, T. (2018, May 29). McChord displays pride in Armed Forces Day. Dvids.

Kelly, A. K. (Director). (2008). Noho Hewa: The Wrongful Occupation of Hawai’i [Motion picture].

Ofamen, B. (2018, May 20). “2018 ARMED FORCES DAY @ JBLM”. YouTube.

Piek, J. (2018, June 14). Base newspaper served readers well for 28 years. Northwest Guardian.

Schroeder, D. (2015, February 18). JBLM Soldiers help clean up local elementary school campus. Army.com.

Tacoma News Tribune. (2017). Brochure.

Vine, D. (2017). Base Nation: How U.S. Military Bases Abroad Harm America and the World. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing.