Afghanistan Team

Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM), formerly Fort Lewis, is an integral part of the military strategy of the United States. Nestled just inside the Puget Sound in western Washington, the base has been a fixture in the annals of U.S. armed conflicts from its inception in 1917. Deploying its tenant units of the Air Force and Army to secure the vast network of bases and influence that the United States military projects on the rest of the world, JBLM continues to provide troops and equipment for the “Global War on Terror” declared in 2001. The first deployment in that conflict was in Afghanistan, in the longest war in U.S. history.

Deployments in Afghanistan

Many units from Fort Lewis, renamed Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM) in 2010, have been thrust into the frontlines of Operation Enduring Freedom, the military code name for the Afghanistan War. They include the 1st Battalion, 1st Special Forces Group (Airborne), a JBLM battalion stationed in Okinawa, Japan, and the 2nd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment stationed in Washington. Afghanistan has historically required unorthodox military engagements as the country’s mountainous and ethnically complex landscape foster unconventional guerrilla-style tactics. The Taliban insurgents, like the mujahedin and other Afghan insurgents before them, easily melt into the civilian population. American forces, like the British and Russian/Soviet occupiers before them, rely on counterinsurgency raids in civilian areas to do battle with the insurgents.

1st Battalion, 1st Special Forces Group (Airborne) has conducted repeated deployments to Afghanistan in support of Special Operations Task Force-South, SOTF-S (Morgan n.d.). JBLM’s 2nd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment is a small-unit tactics maven, as the nation’s premier elite light-infantry force that performs decisive direct-action operations. Approximately 12 men each from the Ranger Regiment and Airborne Special Forces Group (Airborne) have sacrificed their lives in the war for Afghanistan, joining the total of about 85-90 JBLM soldiers who have been Killed In Action in the country (see chronology at end of article).

Conventional forces such as JBLM’s 2nd Infantry Division conduct combat as well, with several deployments to Afghanistan from Stryker Brigade Combat Teams (SBCT). The unit is easily identified by the iconic “Indianhead” shoulder sleeve insignia (shown below). The 2nd ID (as it is colloquially known) has been an integral component to the overall readiness of the U.S. military machine since its historic organization at the Haute-Marne, France in 1917. The 2nd Infantry Division has been at the forefront of the United States’ conflicts since World War I. Stryker Brigades have deployed extensively to Regional Command-South (RC-South), the home of Kandahar Airfield located along Route 1, in the Pashtun-speaking heartland of the Taliban.

JBLM’s units focus on Asia and the Pacific, working in conjunction with local forces in order to accomplish counter-terrorism operations. Conventional units have been consistently deployed in order to provide security in Afghanistan, but conventional deployments are resource- and labor-intensive, and constant deployments of conventional troops attracts strong resistance (see Civilian Dissent in the Iraq War). The public is much more aware of large-scale invasions using conventional forces that deploy troops numbered in the many thousands, and military strategists know that the less obtrusive a defense objective is to the public the longer it will be tolerated to exist. By relying heavily on small Special Operations units, the Department of Defense and other agencies are able to wage multiple conflicts across the globe without substantial opposition in the homeland.

Geopolitics of the Region: The “Great Game”

Since the late 1970s, the United States has spent a considerable amount of time and money trying to exert influence in Afghanistan. To understand the difficulties of establishing control over the country, one has to examine its historical position between empires, and its complex physical and cultural geography that makes it difficult for outside powers to conquer. Many different empires have asserted themselves in the region, including the Greek, Roman, Mongol, Ottoman, British, Russian/Soviet, and now American empires, and only rarely were they (temporarily) successful.

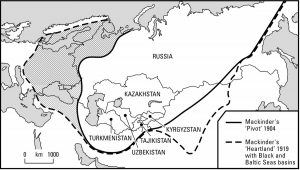

If we view this region through the lens of land power, augmented with new interpretations of Sir Halford Mackinder’s “Geographical Pivot of History” and “Heartland” theories, we can ascertain why U.S. policy makers assign such importance to Afghanistan in the quest to maintain global hegemony. This region sits just below Mackinder’s “natural seat of power” in Central Asia, and a system of bases exist in this country to project military power northward into the “Heartland” (Mackinder 1904). The map shows the initial sketching of Mackinder’s “Geographic Pivot” in conjunction with the expanded “Heartland” displayed with a dashed perimeter. Afghanistan is bisected by the 1904 and 1919 demarcations.

Understanding the historical context of Afghanistan is paramount in understanding today’s conflict. Recent times (mid-18th century until present) have witnessed the growth of Pashtun control over governance, when historically Persian and Turkish governance ideologies prevailed. Starting with the foundation of the modern Afghanistan state by Ahmad Shah Durrani in 1747 (Clements 2003) and continuing on through the installation of the current regime in 2002 (Barfield 2012), Afghanistan has repetitively collapsed as a failed state due to unsustainable power distance (between the governed and the elite), corruption, and war.

The 19th century exhibited intense contestation for Afghanistan in a “Great Games” between empires, with the British Empire projecting military power from its prized possession of India, and the Russian Empire from its Central Asian territories. The British Empire encircled the land-based Russian Empire with sea-based maritime power, and fought three wars against the Afghans, who despite their vast internal ethnic differences united to fend off the colonial power.

The First Anglo-Afghan War (1836-42) was fought between the Emirate of Afghanistan and the British East India Company (Burton n.d.), and ended in a rout of the British. The Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-80) was waged more successfully, and after Abdur Rahman Khan after being appointed Amir of Afghanistan, he wielded despotic rule over the British protectorate. In the Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919), Afghanistan won its independence from the British Empire, with King Amanullah initiating constitutional reforms that ended in civil war and his 1929 ousting by Nadir Shah [King] (Barfield 2012). The Musahiban Period initiated by Nadir Shah and his son Zahir Shah instituted a parliamentary system.

Four Decades of War

When Zahir Shah was deposed in 1973, a period of instability culminated in a 1978 Communist revolution, in which some factions were backed by the Soviet Union. The U.S., Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia financed and armed jihadist rebels known as mujahedin (holy warriors) to attack the government, because of its land reform programs and restrictions on Islamic clerics. When the Islamist insurgency threatened to topple the Communist government in 1979, the Soviet Union occupied Afghanistan.

The Soviet-Afghan War (1979-92) began as a Cold War proxy conflict between the Soviet Union and the U.S., which (like the British) had encircled the Soviets with a string of military bases. The war soon became “Moscow’s Vietnam,” with Soviet forces caught in a counterinsurgency quagmire, which exacerbated the weak state system in Afghanistan (Barfield 2012). In 1989 the Soviet Union withdrew from combat operations in Afghanistan, its Afghan Communist allies collapsed in 1992. The Islamist warlords that were armed by the U.S. took power, issued the first restrictions on women’s rights, and pushed Afghanistan into a bloody four-year civil war that destroyed much of the capital of Kabul.

Mullah Omar emerged from this time period with Sunni ideological training from Pakistan, as well as the military knowledge needed to create the Taliban (“Students”), who took power 1996 (Bergen 2015). Afghans initially welcomed the Taliban’s Islamist rule for its stability, and for an end to opium-funded warlords. But they soon realized that the Taliban only intensified the harsh misogynistic policies initiated by the U.S.-backed warlords, and favored the Pashtun over other ethnic groups (RAWA 2001).

Although the Taliban entered into talks with the U.S. for a gas pipeline, the new government alienated Washington by giving shelter to the Saudi mujahedin leader Osama Bin Laden. Less than a month after the September 11, 2001 terror attacks, the U.S. invaded and installed a government run by the Northern Alliance and other former mujahedin warlords. As many observers predicted, the Taliban launched a rural insurgency much like the one that had defeated the Soviets, backed in particular by Pashtun (who straddle the border with Pakistan), and opposed by Uzbek, Tajik, Hazara, and other ethnic groups from the northern and central regions.

Civil War of Attrition

What started as a Special Operations quest for the Al Qaeda leader Bin Laden turned into a bona fide war of attrition, between the U.S.-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and the Taliban. The Taliban are not an upstart criminal organization that is capitalizing on the weak bureaucratic process of the ISAF-backed Afghan government, but rather they are a zealous complex of Pashtun identity fostered with funds from abroad and from renewed opium production (National Security Archive 2010). Originally, the purpose of the war was to defeat the Taliban and preclude Afghanistan from harboring Al Qaeda terrorists. Then the U.S. proclaimed the war’s goal as establishing a western-style representative democracy, even if its favored Afghan leaders ruled as corrupt autocrats. But the war may also be another continuation of the imperial “Great Game.”

Despite his weakness in incorporating resource economics into his theories, Mackinder’s “Great Game” thesis still holds merit in the contemporary era. If the U.S. and NATO members ceded influence in regions such as the Black Sea or South China Sea, a Eurasian bloc led by Russia and China could dictate the terms of land power in contested borderland regions such as Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq. All of the Central Asian countries lie just beneath an area that Russia sees as her eternal protectorate and an extension of the old Soviet Union; therefore these are places that Vladimir Putin and his regime want to see cleansed of NATO forces in order to establish favorable defense relationships in Russia’s perimeter.

The Afghanistan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) most definitely have the edge in training, financial backing, and sheer numbers, but for what they have in material items they completely lack in execution, conviction, and valor. Desertion of soldiers and police is a key factor in the decline of the ANDSF, much as it was for the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese army. This problem is exacerbated as the conflict rages on, with the Taliban appealing more and more to Afghan youth while the Afghan troops and police get routinely routed. After the troop withdrawals in 2014, ANDSF itself experienced institutional withdrawals, thirsting for U.S intervention to save them from debilitating insurgent Taliban forces.

The government forces of Afghanistan are frequently overrun by the Taliban and they are currently losing ground once previous held by International Security Assistance Forces (ISAF). Afghan forces lost as many as 400 troops in one month of 2018 (Nordland 2018). The northern regions of Afghanistan are experiencing Taliban insurgency, which is unfamiliar this far from the Pashtun tribal lands of the south.

In addition to a stronghold in the strategically important southern province of Helmand, the Taliban controls or contests territory in nearly every province, and continues to threaten multiple provincial capitals. The Taliban briefly seized the capital of Farah Province in May 2018, and in August 2018 captured the capital of Ghazni Province, holding the city for nearly a week before U.S. and Afghan troops took back control. In addition to a U.S. troop increase in 2018, and continuing combat missions, the U.S. military has shifted its strategy to include the targeting of Taliban revenue sources as well as fighters, conducting air campaigns against drug labs and opium production sites (Biddle 2019).

Negotiations between the U.S. and Taliban have been underway in Qatar in 2018-19, working toward a power-sharing agreement with the Kabul government (which has been largely left out of the talks). Periodic ceasefires, such as during the 2018 Muslim holiday of Eid, come and go. The Afghan people are eager for peace, since any citizen born in the past 40 years has known nothing but continuous war. Even the U.S. war in Afghanistan has been going on for so long that American recruits who were yet not born when the U.S. invaded in 2001 are now serving in the armed forces (Phillips 2019).

JBLM Units in Afghanistan

Relatively few combat units were sent to Afghanistan from Fort Lewis in the early days of the Afghanistan War. Even so, the first U.S. soldier killed in the war, Sergeant First Class Nathan Chapman, was assigned to a Special Forces unit at Fort Lewis. After the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, Stryker Brigades and other combat units from Fort Lewis played a pivotal role in Iraq counterinsurgency (see Iraq War). It was not until 2009 when the 5th Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division (reflagged as 2nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division in 2010) deployed to fight the Taliban in Afghanistan. While this deployment was originally scheduled to be to Iraq, mission dictated that 5th SBCT, led by Colonel Harry Tunnell, was to be the first Stryker unit tasked to quell the Taliban in the contentious Regional Command South.

In an early ADVON (advance echelon) movement in 2011, 5-20 Infantry Regiment deployed to Forward Operating Base Pasab and operated as Task Force Regulars in Zhari District, Kandahar Province.

In 2012, Task Force Arrowhead (constituted of 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division) assumed ISAF control in 2012 over Zabul and Kandahar provinces in relief of 116th Brigade Combat Team. Task Force 4-2 (constituted of 4th Stryker Brigade Combat Team 2nd Infantry Division) relieved 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team 2nd Infantry in Kandahar and Zabul provinces. In 2013, 4th Battalion 23rd Infantry Regiment redeployed back to JBLM January 2013 (Morgan n.d.).

The job of the 4,000 soldiers of the 5th Stryker Brigade was “go into areas of southern Afghanistan where NATO’s presence historically has been light and largely ineffective,” in particular the Taliban stronghold of Kandahar province (Fontaine 2009). Many of the soldiers were concentrated in the Arghandab Valley, a fertile swath of farmland near the provincial capital of Kandahar (Bernton 2009b). One of the soldiers told a reporter that the area was “like Vietnam without the napalm.”

Bravo Company is responsible for an area that’s considered a key staging point for Taliban as they organize forays into Kandahar, a major southern city where the insurgents rule by night and set off bombs by day. The Arghandab valley is starkly divided between a flat, barren desert and the fertile stretch of irrigated orchards, vineyards and cornfields along the river. In the 1980s, Soviet troops spent more than a month in an unsuccessful attempt to defeat U.S.-backed mujahedeen forces that took refuge in the orchards. From the green zone, the Taliban fan out to villages, which consist largely of mud-brick homes inside mud-walled compounds that sprout out of the ground in the same dun colors of the surrounding desert (Bernton 2009a).

In 2014, ISAF handed over formal control of the war to ANDSF and began to withdraw the bulk of foreign forces. The following year, NATO (including rotating units from JBLM) initiated Operation Resolute Support to train, advise and assist Afghan troops and police.

Scandals and Controversies involving JBLM units

Pat Tillman “Friendly Fire” cover-up, 2004

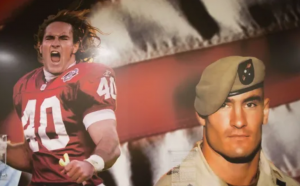

Patrick Tillman was an National Football League (NFL) player who enlisted in the Army after the 9/11 attacks, turning his back on a $3.6 million contract with the Arizona Cardinals. After he enlisted in June 2002, Tillman served in the 2nd Ranger Battalion at Fort Lewis.

Tillman was disappointed when he was initially deployed to Iraq, a war that he viewed as “illegal” (Deveraux 2017). In his first Iraq operation, Tillman’s unit prepared backup for the rescue operation for captured solider Jessica Lynch, which was falsely described to her family and the public, in what Tillman himself called “a big Public Relations stunt” (Krakauer 2009). Corporal Tillman served several combat tours in Iraq, and then in Afghanistan, where his platoon carried out raids ordered by the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC).

Corporal Tillman was killed on April 22, 2004, near Sperah in Khost province. The Army initially told the family and public that Tillman had died under enemy fire. He was awarded the Silver Star, and his memorial service was nationally televised. The Department of Defense knowingly promoted a false story of Tillman bravely charging up a ridge under enemy fire to defend fellow soldiers in his platoon. But by then, an Army investigation had already concluded that he had died under erratic “friendly fire” by other U.S. troops. The Pentagon did not notify the Washington state family of this conclusion until May 28–more than a month after his death (Smith 2006).

In an echo of the Lynch episode, the Bush administration and the U.S. military shamelessly ran with the fabricated account of Tillman’s death. In the hours after Tillman was killed, his uniform and personal effects were destroyed, meaning key forensic evidence — of what many men in his platoon knew was a case of fratricide — was lost. Tillman’s fellow soldiers were told to keep quiet, including in their conversations with his brother Kevin, who was on the mission but at a different location when the fatal shots were fired….Four weeks after the memorial service, Kevin Tillman’s sergeant pulled him aside at their stateside base and told him his brother had been killed by friendly fire. Their mother, Mary, got the news from a reporter calling her for comment. The military withheld key facts from the Tillman family even as it admitted the broad stokes of his death. It would take four years of digging, led chiefly by Mary; seven official investigations; and two congressional hearings before some semblance of the truth surrounding Tillman’s death was pried from the government (Deveraux 2017).

One week after Tillman’s death, JSOC commander General Stanley McChrystal had “sent a memo up the chain of command as a heads-up to the president and other senior officials who might make speeches about the incident. ‘I felt it was essential you receive this information as soon as we detected it…in order to preclude any unknowing statements by our country’s leaders which might cause public embarrassment if the circumstances of Corporal Tillman’s death become public’.” (Deveraux 2017).

Pat’s brother Kevin Tillman explored the Army’s motivation to cover up the facts of his brother’s death: “With any luck, our family would sink quietly into our grief, and the whole unsavory episode would be swept under the rug. However, they miscalculated our family’s reaction. Through the amazing strength and perseverance of my mother, the most amazing woman on earth, our family has managed to have multiple investigations conducted. However, while each investigation gathered more information, the mountain of evidence was never used to arrive at an honest or even sensible conclusion” (Bar-Lev 2010).

Pat Tillman’s story was told by his mother Mary Tillman in her book Boots on the Ground by Dusk (Tillman & Zacchino 2008), and by Jon Krakauer in his book Where Men Win Glory (Krakauer 2009), and in the documentary below, The Tillman Story (Bar-Lev 2010), and inspired the “friendly fire” documentary A Second Knock at the Door (Grimes 2012).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=laNQ5J2caOY

“Kill Team” Murders in Maywand District, 2010

In January-May 2010, a group of Fort Lewis soldiers assigned to 3rd Platoon, Bravo Company, 2nd BN 1st Infantry Regiment operated outside of any military or moral authority and staged the deaths of at least three unarmed Afghan civilians in Maywand district, Kandahar Province. The self-proclaimed “Kill Team” staged weapons near the victims to justify the killings.

Rolling Stone reporter Mark Boal described one of the killings:

The loud report of the guns echoed all around the sleepy farming village. The sound of such unexpected gunfire typically triggers an emergency response in other soldiers, sending them into full battle mode. Yet when the shots rang out, some soldiers didn’t seem especially alarmed, even when the radio began to squawk. It was Morlock, agitated, screaming that he had come under attack. On a nearby hill, Spc. Adam Winfield turned to his friend, Pfc. Ashton Moore, and explained that it probably wasn’t a real combat situation. It was more likely a staged killing, he said – a plan the guys had hatched to take out an unarmed Afghan without getting caught.

Back at the wall, soldiers arriving on the scene found the body and the bloodstains on the ground. Morlock and Holmes were crouched by the wall, looking excited. When a staff sergeant asked them what had happened, Morlock said the boy had been about to attack them with a grenade. “We had to shoot the guy,” he said.

It was an unlikely story: a lone Taliban fighter, armed with only a grenade, attempting to ambush a platoon in broad daylight, let alone in an area that offered no cover or concealment. Even the top officer on the scene, Capt. Patrick Mitchell, thought there was something strange about Morlock’s story. “I just thought it was weird that someone would come up and throw a grenade at us,” Mitchell later told investigators.

But Mitchell did not order his men to render aid to Mudin, whom he believed might still be alive, and possibly a threat. Instead, he ordered Staff Sgt. Kris Sprague to “make sure” the boy was dead. Sprague raised his rifle and fired twice.

As the soldiers milled around the body, a local elder who had been working in the poppy field came forward and accused Morlock and Holmes of murder. Pointing to Morlock, he said that the soldier, not the boy, had thrown the grenade…

To identify the body, the soldiers fetched the village elder who had been speaking to the officers that morning. But by tragic coincidence, the elder turned out to be the father of the slain boy. His moment of grief-stricken recognition, when he saw his son lying in a pool of blood, was later recounted in the flat prose of an official Army report. “The father was very upset,” the report noted (Boal 2011).

In another incident, the soldiers lied to their platoon commander about the reasons for killing a cleric on May 2, 2010, causing him to mislead village elders that the cleric had acted aggressively (Whitlock 2010). Of the 13 soldiers involved in the various murders, Staff Sergeant Calvin Gibbs, Specialist Jeremy Morlock, and Private First Class Andrew Holmes (shown in the photo posing with the body of Gul Mudin) were convicted (Der Spiegel 2011). Morlock was sentenced to 24 years by a military tribunal after pleading guilty, and testified against his fellow soldiers as part of a plea bargain (Boal 2011).

Panjwai Massacre, 2012

In March 2012 in Panjwai district, Kandahar province, Staff Sergeant Robert Bales committed the heinous act of killing four men, four women, and eight children, in an event that would be later known as the Panjwai Massacre (BBC 2012). Bales launched his assault on the local populace from Village Stability Platform (VSP) Belambai in the dead of night, single-handedly creating an atrocity not seen since the My Lai massacre in 1968 (Vaughn 2015).

BBC News reported that Bales “is said to have broken into three homes in three different locations in Panjwai district – the villages of Alkozai and Najeeban and another settlement known locally as “Ibrahim Khan Houses.” ….by the end of the attack, 16 people, nine of them children, were dead and five wounded. Some of the bodies had been set on fire. The killings have devastated these remote farming communities” (BBC News 2014).

Alkozai resident Samiullah said his mother was killed by Sgt Bales, along with three others, adding:

In the beginning, ISAF [NATO’s International Security Assistance Force] claimed they started fighting against terrorism in Afghanistan, but now it seems they are fighting against Afghans…That village, that house, always reminds me of how the American soldier attacked my family and murdered my mother.” Samiullah has left his village to live in Kandahar city, where he said he does not have to worry about soldiers or the Taliban raiding his home at night. The massacre outraged Afghans, and the parliament demanded a public trial before the Afghan people for the “brutal and inhuman” killings. The president, Hamid Karzai, described the incident as “unforgiveable” (Agence France-Presse 2012).

The Kill Team murders, Panjwai Massacre, and incidents of crime and abuse around JBLM (see Social Crises) reinforced an image of JBLM as a “base on the brink,” as described in the military newspaper Stars and Stripes (Turner 2010). One veterans’ group began to describe JBLM as a “rogue base” that had failed civilians, soldiers, and their families. After Panjwai, the executive director of G.I. Voice, which ran the Coffee Strong resource center for soldiers near JBLM (see Military Dissent), commented,

This was not just a rogue soldier…If Fort Lewis was a college campus, it would have been closed down years ago….In 10 years of war, JBLM has produced a Kill Team, suicide epidemic, denials of PTSD treatment, denials of human rights in the Brig, spousal abuse and a waterboarded daughter, murders of civilians including a park ranger, increased sex crimes, substance abuse, DUIs, police shootings of GIs, police violence toward protesters, differential treatment of GIs, and much more…These abuses are not because of a few bad apples, but because of the base’s systematic dehumanization of soldiers and civilians, both in occupied countries and at home (My Northwest 2012).

Whatever the verdict of history about the effects of JBLM’s deployments on civilians and soldiers in Afghanistan, it is undeniable that JBLM units have had a major effect on the conduct and direction of the Afghanistan War. From the initial invasion in pursuit of Al Qaeda to the counterinsurgency battles with the Taliban, the provincial reconstruction process, and the 2021 evacuation of Kabul (Bernton 2021), JBLM units have played a key role in shaping the future of Afghanistan.

It is important to remember the civilian casualties in America’s longest war, and the U.S. military personnel injured and killed, whatever the circumstances. There is no better way to conclude this study than to remember the names of the 91 Fort Lewis / JBLM soldiers who were Killed In Action (KIA) in the 20-year war in Afghanistan, so they are never forgotten at home.

Fort Lewis / JBLM soldiers Killed In Action in Afghanistan

Rank abbreviations on KIA chronology

PFC : Private First Class

SPC: Specialist

CPL: Corporal

SGT: Sergeant

SSG: Staff Sergeant

SFC: Sergeant First Class

MSG: Master Sergeant

2LT: Second Lieutenant

1LT: First Lieutenant

CPT: Captain

Unit abbreviations on KIA chronology

AASLT: Air Assault

BN: Infantry Battalion

CO: Company

FAR: Field Artillery Regiment

HQ: Headquarters

ID: Infantry Division

INF: Infantry Regiment

RGR: Ranger Regiment

SBCT: Stryker Brigade Combat Team

SFG(A): Special Forces Group (Airborne)

Sources for KIA chronology

Afghanistan Fatalities [AF]

Green Beret Memorial Wall [GB]

Honor Our Fallen [HF]

Comprehensive listing of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) U.S. Military Casualties – Names of Fallen (May 22, 2015).

Rank / Name / Date KIA / District, Province (of incident) / Military Unit / [Source]

SFC Nathan Chapman 1/4/02 in Khost, Paktika with 3rd BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

SGT Jay A. Blessing 11/14/03 in Asadabad, Kunar with 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

CPL Patrick D. Tillman 4/22/04 in Sperah, Khost with CO A, 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

SGT Jeremy R. Wright 1/3/05 in Asadabad, Kunar with 2nd BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

SFC David L. McDowell 4/29/08 near Camp Bastion, Helmand with 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

SPC Christopher Gathercole 5/26/08 in Ghazni with 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

PFC Jonathan C. Yanney 8/18/09 in Arghandab, Kandahar with HQ CO 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Troy O. Tom 8/18/09 in Arghandab, Kandahar with CO A, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Dennis M. Williams 8/25/09 in Kandahar with CO A, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

CPT Cory J. Jenkins 8/25/09 in Kandahar with HQ CO, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

CPT John L. Hallett III 8/25/09 in Kandahar with CO A, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SFC Ronald W. Sawyer 8/25/09 in Kandahar with HQCO 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

PFC Jordan M. Brochu 8/31/09 in Shuyene Sufia, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Jonathan D. Welch 8/31/09 in Shuyene Sufia, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Tyler R. Walshe 8/31/09 in Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Andrew H. McConnell 9/14/09 in Kandahar with 2nd BN, 1st INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

1LT David T. Wright II 9/14/09 in Kandahar with 2nd BN, 1st INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Joseph V. White 9/24/09 in Nangarhar with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Edward B. Smith 9/24/09 in Nangarhar with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Titus R. Reynolds 9/24/09 in Nangarhar with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Kevin J. Graham 9/26/09 in Kandahar with CO A, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Michael A. Dahl Jr. 10/17/09 in Kandahar with CO B, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Kyle A. Coumas 10/21/09 in Kandahar with CO A, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

PFC Brian R. Bates Jr. 10/27/09 in Kandahar with 2nd BN, 1st INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

PFC Christopher I. Walz 10/27/09 in Arghandab, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Jared D. Stanker 10/27/09 in Arghandab, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Patrick O. Williamson 10/27/09 in Arghandab, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Issac B. Jackson 10/27/09 in Arghandab, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Dale R. Griffin 10/27/09 in Arghandab, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SFC Luis M. Gonzales 10/27/09 in Arghandab, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Aaron S. Aamot 11/5/09 in Jelewar, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Gary L. Gooch Jr. 11/5/09 in Jelewar, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 17th INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Joseph M. Lewis 11/17/09 in Kandahar with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT David H. Gutierrez 12/25/09 in Kandahar with 2nd BN, 1st INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Kyle J. Wright 1/13/10 in Kandahar with 2nd BN, 1st INF, 5th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Adam J. Ray 2/9/10 in Kandahar with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 2nd ID [AF]

SSG Rusty Hunter Christian 1/28/10 in Oruzgan with CO C, 2nd BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

SGT Joel D. Clarkson 3/16/10 in Farah with CO A, 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

PFC James L. Miller 3/29/10 in Dashat, Bamyan with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 2nd ID [AF]

MSG Mark W. Coleman 5/2/10 in Kandahar with CO C, 2nd BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

PFC Jason D. Fingar 5/2/10 in Durai, Helmand with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 2nd ID [AF]

SFC Dae Han Park 3/12/11 in Kajran, Daykundi with CO C, 3rd BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

SFC Wyatt A. Goldsmith 7/15/11 in Helmand with CO A, 3rd BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

SGT Tyler N. Holtz 9/24/11 in Wardak with CO B, 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

SPC Ricardo Cerros Jr. 10/8/11 in Logar with CO B, 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

PFC Christopher A. Horns 10/22/11 in Kandahar with CO C, 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

SFC Kristoffer B. Domeji 10/22/11 in Kandahar with HQCO, 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

SFC Benjamin B. Wise 1/15/12 in Balkh with CO A, 3rd BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

1LT David A. Johnson 1/25/12 in Kandahar with 5th BN, 20th INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Philip Schiller 4/11/12 in Panjwai, Kandahar with 1st BN, 23rd INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Nicholas M. Dickhut 4/30/12 in Zhari, Kandahar with 5th BN, 20th INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Jabraun S. Knox 5/18/12 in Asadabad, Kunar with 1st BN, (AASLT), 377th FAR, 17th Fires Brigade [AF]

SGT Michael J. Knapp 5/18/12 in Asadabad, Kunar with 1st BN, (AASLT), 377th FAR, 17th Fires Brigade [AF]

2LT Travis A. Morgado 5/23/12 in Zhari, Kandahar with 5th BN, 20th INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

PFC Cale C. Miller 5/24/12 in Maiwand, Kandahar with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 2nd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Vilmar Galarza Hernandez 5/26/12 in Zhari, Kandahar with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 2nd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SSG Alexander G. Povilaitis Jr. 5/31/12 in Zhari, Kandahar with 14th Engineer BN, 555th Engineer Brigade [AF]

SPC Gerardo Campos 6/2/12 in Maiwand, Kandahar with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 2nd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SFC Barett W. McNabb 6/12/12 in Khakrez, Kandahar with 562nd Engineer CO, 2nd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Trevor A. Pinnick 6/12/12 in Panjwai, Kandahar with 1st BN, 37th FAR, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Joseph M. Lilly 6/14/12 in Panjwai, Kandahar with 1st BN, 37th FAR, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Jose Rodriguez 6/19/12 in Kandahar with 4th BN, 23rd INF, 2nd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SSG Raul M. Guerra 7/4/12 in Spin Boldak, Kandahar with 502nd Military Intelligence BN, 201st Surveillance Brigade[AF]

SGT Juan Navarro 7/7/12 in Panjwai, Kandahar with Apache CO, 1st BN, 23rd INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Sterling Wyatt 7/11/12 in Kandahar with 5th BN, 20th INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Michael E. Ristau 7/13/12 in Qalat, Zabul with 5th BN, 20th INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

1LT Sean R. Jacobs 7/26/12 in Khakrez, Kandahar with 2nd BN, 17th FAR, 2nd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT John E. Hansen 7/26/12 in Khakrez, Kandahar with 2nd BN, 17th FAR, 2nd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SPC Michael R. Demarsico 8/16/12 in Panjwai, Kandahar with CO C, 1st BN, 23rd INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Louis Torres 8/22/12 in Kandahar with 2nd BN, 3rd INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SSG Jeremie S. Border 9/1/12 in Ghazni with CO A, 1st BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

SGT Sapuro B. Nena 9/16/12 in Zabul with 2nd BN, 3rd INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

PFC Genaro Bedoy 9/16/12 in Zabul with 52nd INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

PFC Jon R. Townsend 9/16/12 in Zabul with 1st BN, 23rd INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Thomas R. Macpherson 10/12/12 in Ghazni with CO D, 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

SPC Brittany B. Gordon 10/13/12 in Kandahar with 572 Military Intelligence BN, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT Robert J. Billings 10/13/12 in Spin Boldak, Kandahar with 5th BN, 20th INF, 3rd SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SSG Kenneth W. Bennett 11/10/12 in Sperwan Ghar, Panjwai, Kandahar with 3rd Ordnance BN, [AF]

SSG Rayvon Battle Jr. 11/13/12 in Kandahar with 38th Engineer CO, 4th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SSG Wesley R. Williams 12/10/12 in Kandahar with 1st BN, 38th INF, 4th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SSG Nicholas J. Reid 12/13/12 in Sperwan Ghar, Panjwai, Kandahar with 53rd Ordnance CO (EOD) 3rd Ordnance BN, [AF]

PFC Markie T. Sims 12/29/12 in Panjwai, Kandahar with 38th Engineer CO, 4th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SGT David J. Chambers 1/16/13 in Panjwai, Kandahar with 1st BN, 38th INF, 4th SBCT, 2nd ID [AF]

SFC James F. Grissom 3/21/13 in Paktika with 4th BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

SSG Michael H. Simpson 5/2/13 in Arian, Ghazni with 4th BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

SSG Matthew V. Thompson 8/23/16 in Helmand with 3rd BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

SFC Reymund R. Transfiguracion 8/12/18 in Helmand with 3rd BN, 1st SFG(A) [GB]

SGT Leandro Jasso 11/24/18 in Nimroz with CO A, 2nd BN, 75th RGR [HF]

SGT Cameron Meddock 1/13/19 in Jawand, Badghis with CO A, 2nd Battalion, 75th RGR [HF]

SFC Dustin B. Ard 9/3/19 in Zabul, with 2nd BN, 1st Particular Forces Group (Airborne).

SFC Jeremy W. Griffin 9/16/19 in Wardak, with 3rd BN, 1st SFG(A)

Thanks to T.M. for research and initial drafts and Z.G. for additional research and final draft.

Sources

Afghanistan Fatalities. (n.d.).

Agence France-Presse. (2012, November 6). Site of alleged massacre by US soldier now a ghost town. AFP.

Anderson, Ben (2018, February 15). Afghans Are Facing the Deadliest Taliban Yet. Vice News.

Bar-Lev, Amir. (2010). The Tillman Story [documentary]. Website & full film on YouTube

BBC News. (2012, March 17). How it happened: Massacre in Kandahar. BBC.

Bergen, Peter. (2015, August 21). The enigmatic Mullah Omar and his legacy. CNN.

Bernton, Hal. (2009a, October 2). For troops, Afghanistan ‘like Vietnam without napalm.’ Seattle Times.

Bernton, Hal. (2009b, October 3). For U.S. Troops in Afghanistan, home is where they make it. Seattle Times.

Bernton, Hal. (2021, August 17). Air Force to investigate Afghan civilian deaths as JBLM-based C-17 took off from Kabul airport. Seattle Times.

Biddle, S. (2019, February 15). Global Conflict Tracker: War in Afghanistan. Council on Foreign Relations.

Boal, Mark. (2011, March 28). The Kill Team: How U.S. Soldiers in Afghanistan Murdered Innocent Civilians. Rolling Stone.

Burton, A. (n.d.). On the First Anglo-Afghan War, 1839-42: Spectacle of Disaster. Branch Collective.

Clements, F. A. (2003). Conflict in Afghanistan: A historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC Clio.

Deveraux, Ryan. (2017, September 28). The NFL, the Military, and the Hijacking of Pat Tillman’s Story. The Intercept.

Elias, Barbara (2007, August). Pakistan: The Taliban’s Godfather. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book 227.

Elias, Barbara. (2010, September). “No-Go” Tribal Areas Became Basis for Afghan Insurgency Documents Show. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book 325.

Encyclopaedia Britannica (2018, December 6). Taliban. Britannica.com.

Fontaine, Scott. (2009, November 9). A soldier back from the brink. Tacoma News Tribune.

Foundation for Defense of Democracies. (n.d.). Long War Journal. FDD.

Green Beret Memorial Wall. (n.d.).

Grimes, Christopher E. (2012). A Second Knock at the Door: A Documentary on Friendly Fire.

Grossman, R. (2016, June 22). Trump, like McCarthy, is master of conspiracy and innuendo. Chicago Tribune.

Hegseth, P. (2018, May 04). Mapping Taliban Control in Afghanistan. Long War Journal.

Honor Our Fallen. (n.d.).

Krakauer, Jon. (2009). Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman. New York: Knopf.

Mackinder, Harold J. (1904, April). The Geographical Pivot of History. The Geographical Journal 23(4): 421-437.

Morgan, W. (n.d.). Afghanistan Order of Battle. Understanding War.

MSNBC. (2008, May 5). Pat Tillman’s mom seeks truth. MSNBC.com.

My Northwest. (2012, March 12). Veterans group calls JBLM a ‘rogue base.’ MyNorthwest.com.

Nordland, R. (2018, September 21). The Death Toll for Afghan Forces Is Secret. Here’s Why. New York Times.

Nordland, R., & Rahim, N. (2018, August 14). The Afghan army’s last stand at Chinese Camp. Seattle Times.

Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). (2015, May 22.) U.S. Military Casualties – Names of Fallen.

Pat Tillman Foundation. (2019).

Phillips, Michael M. (2019, February 25). Marine Recruits Learn an Important Lesson: What Happened on 9/11. Wall Street Journal.

Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA). (2001, November 15). The People of Afghanistan Do Not Accept Rule by Northern Alliance. Counterpunch.

Sharapova, S., & Megoran, N. (2013, March 19). Introduction: Halford Mackinder and Central Asia. In Central Asia in International Relations: The Legacies of Halford Mackinder. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Smith, Gary. (2006, September 11). Remember His Name. Sports Illustrated.

Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction. (2018, October 30). Quarterly Report for the United States Congress. SIGAR.mil.

Der Spiegel. (2011, March 24). Murder in Afghanistan: Court Sentences ‘Kill Team’ Soldier to 24 Years in Prison. Spiegel Online.

Tillman, Mary & Narda Zacchino. (2008). Boots on the Ground by Dusk: My Tribute to Pat Tillman. New York: Random House.

Turner, D. (2010, December 27). Joint Base Lewis-McChord rocked by scandal. Stars and Stripes.

United States Central Command. (n.d.) Operation Resolute Support. USCENTCOM.

Vaughan, B. (2015, October 21). Robert Bales Speaks: Confessions of America’s Most Notorious War Criminal. Gentlemen’s Quarterly.

Wikileaks. (n.d.) Afghanistan: The Enigmatic Mullah Omar and Taliban decision-making. Wikileaks.

Whitlock, Craig. (2010, October 27). Unit tried to defend killing at heart of Afghan probe. Washington Post.