Zoltán Grossman

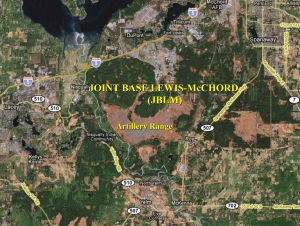

An enormous military installation such as Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM) is usually not thought of as a place of environmental protection and restoration. Militaries around the world are a primary contributor to toxic pollutants, greenhouse gasses, and natural habitat destruction. The U.S. Department of Defense, in particular, is one of the world’s largest polluters (Nazaryan 2014). The constant firing of artillery and small arms on JBLM’s impact areas has historically had a detrimental effect on the health of the land, water, fish and wildlife, and human beings.

But in Washington state, strong public environmental consciousness and tribal treaty rights have combined to pressure JBLM at to stand above other U.S. bases in protecting endangered species, prairies, and forests, and ecologically restoring natural habitats on its 87,000 acres. These gains are threatened by continuing problems connected to the munitions themselves, which release toxic compounds into the soil and groundwater.

Endangered Species

Military bases around the country have ironically become a haven for wildlife, as endangered species lose habitat to agriculture and urban development in civilian areas. JBLM conservation program director Jeff Foster observed that military bases “tend to be reservoirs for biodiversity – lots of rare plants and animals and plant communities – because they aren’t developed for other purposes, like cities and agriculture.…. But that can sometimes be a problem. Sometimes the needs of those species conflict with the needs of military training” (Price 2016).

JBLM’s Public Works – Environmental Division contains the Fish and Wildlife Program, whose mission “is to protect, maintain, and enhance the various ecosystems on the installation to promote native biodiversity and support the military mission.” To accomplish this mission “we monitor native and non-native species (plants and animals), conduct habitat restoration to help manage invasive species in order to improve habitat for native species as well as for military training purposes, and we de-conflict potential Endangered Species Act (ESA) violations by consulting with military units prior to training missions occurring in designated critical habitat.” (JBLM Fish and Wildlife). It partners with state and federal agencies, the Nisqually Indian Tribe, Nisqually River Foundation, Center for Natural Lands Management, Cascadia Prairie Oak Partnership, City of Roy, The Evergreen State College, and other entities.

One of the key reasons for the founding of Fort Lewis in 1917 is that its large prairie offered open space for artillery training (see Training and Testing). Much of the Program’s mission focuses on protecting and restoring the prairie lands, which were left by receding glaciers, and are rarely found in the heavily developed Puget Sound region. In springtime, large fields of blue camas bulb plants (which local tribes have long used a food source) blanket JBLM impact areas on the Nisqually Prairie, or 31st Division Prairie.

JBLM contains the largest remaining areas of historic glacial outwash prairies. Out of all of the glacial outwash prairie that previously existed there is only 5% remaining and of that, JBLM is home to ~95%. Along with this JBLM also has Garry oak (also known as Oregon White oak) woodlands which are Washington’s only native oaks, Ponderosa pine savannahs which are more commonly found east of the Cascade Mountains, and many wetlands some of which are kettle wetlands which were formed by receding glaciers. Each of these habitats are rare in western Washington and provide a very distinct ecosystem that contributes to wildlife diversity (JBLM Fish and Wildlife).

These unique habitats harbor federally threatened or endangered species, which the Department of Defense is obligated to protect as a federal agency. Endangered species include the Taylor’s checkerspot butterfly, which was once commonly found on Pacific Northwest prairies, but now consist of only 14 scattered populations (WFWO). The artillery impact area at JBLM contains some of the few remaining natural populations of the butterflies, “due to limited access to the area and wildfires that are unintentionally started every year by training activities” (JBLM Fish and Wildlife).

|

|

|

|

The Mazama Pocket Gopher was once widespread on South Puget Sound prairies, but is now a threatened species (WFWO). It has become “increasingly rare as suitable habitat has been lost to development, degraded by invasive species such as Scotch Broom, and naturally converted to forests due to the absence of fires, which were once common on the landscape” (JBLM Fish and Wildlife).

The Streaked Horned Lark is a small ground nesting bird, “which makes it especially vulnerable to recreation and military training impacts. These birds prefer open areas with few shrubs and sparse vegetation, like road edges and airfields which are mowed often resulting in nests being destroyed.” The Western Bluebird is a regional species of concern, which has been “negatively impacted by the introduction of competing invasive species and the removal of snags from the landscape. Nest boxes have been distributed throughout JBLM to support the species across the installation and to promote dispersal to other areas within its range” (JBLM Fish and Wildlife).

One of the tools that JBLM uses to extend prairie habitat is to acquire off-based parcels to offset the damage to prairie habitat on base. The Army Compatible Use Buffer (ACUB) program began in 2006 “to reduce environmental encroachment (restrictions on training) on JBLM associated with the listing or potential listing of prairie species under the Endangered Species Act by supporting the conservation of these species on lands off the installation.” The ACUB program aims to acquire an interest in parcels with existing or restorable prairie, and “manage these parcels, jointly with currently protected (public or private ownership) prairie lands, for recovery of prairie species,” often through partnerships. The program also upgrades prairie habitat on base by removing invasive species, planting native plant species, reintroducing animal species, and carrying out prescribed prairie burnings (JBLM ACUB).

Fisheries

Part of the mission of JBLM’s Fish and Wildlife program is to protect and restore runs of salmon (Chinook, Chum, Coho, and Pink) and threatened steelhead in the tributaries of the Nisqually River, notably Muck Creek. The base makes up 12 percent of the Nisqually River Watershed, which originates on federal land at Mount Rainier National Park, and ends at the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge. The Army has often partnered with the Nisqually Tribe, the signatory to the treaty that upholds tribal fishing rights, to conduct fish surveys and habitat restoration plans. The Army also allowed a tribal fish hatchery to be built on base (see Nisqually Tribe).

Before the 1980s, the Army would drive tanks and other armored vehicles through the streambeds, severely damaging fish habitat, so the Tribe pressured the base to install bridges. Fragile habitat areas rich in springs were sometimes shelled in artillery trainings, or logged for timber, so the Tribe negotiated with the Army for new regulations and procedures (Wilkinson 2000, 66-85).

Nisqually treaty rights leader Billy Frank Jr. commented, “You can say that the Army was our enemy when they took our land on the other side of the river…. These are different times. It has to do with the survival of a people….The Army is a much better land manager than the Forest Service…..The commanding general is the boss….when I go across the river to Fort Lewis, I know who’s in charge. When he tells the soldiers ‘Don’t drive any more tanks across Muck Creek’–that’s what going to happen. Boy, that is powerful, when you’ve gotten a handshake with the General…” (Wilkinson 2000, 80).

The Army and Tribe have joined in habitat restoration of the Muck Creek system, removing invasive species such as reed canary grass, that “clog up the stream channel making migration difficult for steelhead and other salmon and eliminates open gravely areas needed for spawning” (JBLM Fish and Wildlife). They shore up the riparian zones along streams with native vegetation, so the streambanks do not erode sediments that cover redds (fish egg nests) with silt, and so the water is cooled by shade. For background, see the Nisqually Watershed Podcast on Fort Lewis from Evergreen’s Conceptualizing Native Place program (Bean Mortinson, Duerr-Miller, & Vieau 2009).

Forestry and Ecological Restoration

Forest management is a major concern in Washington state, partly because of the negative impacts of clearcutting and erosion on fish habitat. JBLM practices selective timber harvesting on base, but does not harvest the old-growth stands along the 20-mile stretch of the Nisqually River that it within the base. JBLM has 61,000 acres of “forest, woodland, and savanna, most of which are actively managed for military training and for commercial and non-commercial uses.” The mission of its Forestry Branch is to “provide good stewardship of the forested training lands of JBLM by ensuring the continued existence of a healthy forest that supports military training, sustains native plants and animals, and benefits local communities” (JBLM Forestry Branch).

In 2002, the base became the first federally owned property to be certified as a sustainable forestry operation by the Forest Stewardship Council, and has been recertified twice since then. Forest managers use variable-density thinning, which “creates more structurally diverse forests over time,” and replant areas with biodiverse plant species. Local loggers and sawmills bid on the logging work, and 40 percent of net revenue supports schools and roads in Pierce and Thurston counties (JBLM Forestry Branch).

In summertime, JBLM conducts prescribed burns to “reduce the fuel load that can cause devastating wildfires, improve training lands for service members and enhance fire-dependent habitats, and at the same time suppresses unplanned wildfires started by exploding munitions” (JBLM Wildland Fire). Although these fires sometimes mimic natural fire management, they also occur in the wrong ecosystems and during the wrong seasons, making them harmful to plant and animal species.

The Environmental Division’s Ecology Program carries out ecological restoration of white oak and native ponderosa pine woodlands and savannas, which (together with native prairie) provides habitat for many wildlife species. Oak woodlands “are a declining habitat in southern Puget Sound that many wildlife species depend upon. The pine is native, and, where the understory is native prairie, forms a globally unique plant community found only on and adjacent to JBLM. The purpose of restoration is to move these woodlands/ savannas back towards their pre-European condition, reintroduce fire as a natural process, and improve habitat for wildlife” (JBLM Forestry Branch).

Munitions Compounds in Soil and Water: RDX, HMX, TNT, NG

Despite JBLM’s successes in protecting and restoring plant, fish, and wildlife habitat on the surface, the use of munitions on base has created a largely unseen problem beneath the surface. Toxic compounds in explosive material, and the propellant used to project shells, can seep into the soil and groundwater. Munitions compounds of concern at JBLM include the explosives hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX), octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine (HMX), and 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), and the propellant ingredient nitroglycerin (NG).

Soil scientist John Pichtel documented, “Energetic materials comprise both explosives and propellants. When released to the biosphere, energetics are…contaminants which pose toxic hazards to ecosystems, humans, and other biota. Soils worldwide are contaminated by energetic materials from manufacturing operations; military conflict; military training activities at firing and impact ranges; and open burning/open detonation of obsolete munitions” (Pichtel 2012).

Pichtel added, “In the US alone, thousands of military sites are listed as contaminated by energetic compounds. 50 million acres are affected by bombing and other training activities…. Significant public health emergencies resulting from soil contamination have launched demands by local citizenry for remediation measures” (Pichtel 2012).

In humans TNT is associated with abnormal liver function and anemia, and both TNT and RDX have been classified as potential human carcinogens….The effects of RDX on mammals are generally characterized by convulsions. Deaths in rats were associated with congestion in the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. Factory employees in Europe and the US have suffered convulsions, unconsciousness, vertigo, and vomiting after RDX exposure. Information is limited concerning health effects of HMX. The USEPA has established lifetime exposure drinking water health advisory limits for TNT, RDX, and HMX… Acute exposure to NG can cause headaches, nausea, convulsions, cyanosis, circulatory collapse, or death. Chronic exposure may result in severe headaches, hallucinations, and skin rashes. (Pichtel 2012).

The Army has estimated that “over 1.2 million tons of soil across its various facilities is currently contaminated due to explosives….TNT and other explosives are known Group C carcinogens dangerous to both humans and the environment, thus justifying the necessity to remediate these contaminated sites before they create a greater hazard…. The majority of TNT and RDX contamination found on training ranges today is lying on and near the surface (less than 1 foot underground) and is the primary source of soil, ground, and surface water contamination” (Anderson & Ventola 2015) .

JBLM “is one of the world’s largest military complexes with an almost 100-year history…Currently, JBLM has 115 live fire ranges. Perhaps more unsettling than this is that JBLM also has 16 housing communities on the base, which, in regards to groundwater contamination caused by the firing ranges, are dangerously nearby” (Anderson & Ventola 2015).

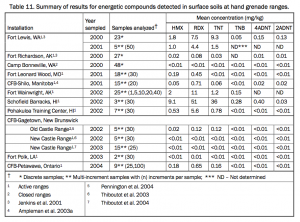

Hand grenade ranges are of particular concern, given the presence of RDX, TNT, and HMX in the explosive charge. A 2001 study of soil samples from grenade ranges at Fort Lewis and Alaska’s Fort Richardson “were found to have detectable concentrations of RDX. TNT… and HMX were often detected as well.” The concentrations in the Fort Lewis samples were an order of magnitude higher than at Fort Richardson (Jenkins, Pennington, & Ranney et al 2001).

A 2012 Environmental Protection Agency report studied nitroglycerin around active anti-tank rocket ranges at JBLM and seven other bases, and found high concentrations near firing points (USEPA 2012). A 2013 study of soils collected at JBLM and two other bases showed that soils rich in organic carbon slow the transport of nitrogen-rich munitions compounds more than clay soils (Sharma, Mayes, & Tang 2013).

A 2017 investigative report by ProPublica documented the health risks of RDX, and Pentagon attempts to sidetrack federal regulations on the toxic compound:

From the first reports of RDX contamination on American soil, the Pentagon has either ignored or actively sought to discount RDX’s threat to public health and the environment, according to ProPublica’s review of thousands of pages of EPA and Pentagon documents and the accounts of more than 23 current and former officials and lawmakers. When confronted with evidence of the risk posed by RDX, the Pentagon tried to get its bases exempted from almost any kind of environmental oversight… When that failed, the Department of Defense financed an array of studies that minimize evidence of RDX’s potential to cause cancer and other health problems, and then pressed the EPA to relax its classification of RDX’s cancer threat — and the environmental cleanup standards that are recommended along with it, Pentagon and EPA records show…. The Pentagon’s existing obligations to address thousands of contaminated installations are already daunting, with costs that could top $70 billion. If EPA officials were to decide that RDX ‘likely’ causes cancer, it could lead to new regulations and demands for more thorough cleanups, adding significant costs (Lustgarten 2017).

Other munitions concerns at JBLM include noise pollution from artillery firing (see Noise Issues), radiation potentially lingering from the possible use of Depleted Uranium shells on the firing range in the 1960s (see Training and Testing), the Superfund site at the Logistical Center (see Mapping JBLM), and the release of toxins from Unexploded Ordnance.

Unexploded Ordnance (UXO)

Exploding munitions are an obvious threat to human health and safety. For example, until the late 1970s, the Army launched shells from the Pierce County part of Fort Lewis, over the Nisqually Reservation, to an impact area in Thurston County. Some of the shells fell short, causing fires, including one near a tribal fireworks stand (Wilkinson 2000, 84).

But less obvious is that shells and bombs are a risk to health and safety even if they do not explode on impact. The Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program found in 2004 that “millions of acres of range sites are potentially contaminated with unexploded ordnance (UXO), including bombs, missiles, and landmines. Depending on site conditions and UXO characteristics, the time to perforation (i.e., corrosion breakthrough of the UXO metallic casing) can vary from roughly 10 years to several thousand years. The potential movement of energetic materials out of perforated UXO and into groundwater has become a primary environmental concern” (Packer 2004).

JBLM has an active program to remove Unexploded Ordnance, marking and controlling areas know to contain UXO, but a large amount of JBLM property “has been used to conduct and support live-fire training in the past. This has resulted in the possibility of encountering UXO in areas that are not marked and may not appear hazardous” (JBLM UXO Awareness).

Conclusion

Stories of environmental protection at JBLM are rich in ironies. If an endangered plant or animal survives artillery shell explosions on an impact range, it actually has a better chance of survival than it would outside the base. Clean springwater feeds a fish hatchery on base, but toxic compounds from munitions could potentially bioaccumulate in the fish. Military operations with the mission of protecting citizens may expose those same citizens to unhealthy contamination.

The very presence of the base, though its operations have caused harm to natural species and groundwater, also prevents other harms. If the base ever closed—an unlikely prospect given continuing tensions in East Asia and the Middle East—the federal property could be privatized and opened up to condo development and urban sprawl. As Billy Frank Jr. asked, “Who do you want there—the army, or a bunch of subdivisions?” (Wilkinson 2000, 81).

Many critics of the base agree that JBLM has done a better job than other military bases in prioritizing environmental protection, and commend it for doing so. But that is a low bar, so the garrison command could set higher standards and confront difficult issues such as munitions compounds, artillery noise, and harmful fires. The scale of JBLM’s military operations around the world can also be factored into assessing its actual effect on the Earth and its inhabitants.

Sources

Anderson, Aaron, and Andrea Ventola. (2015). Investigating Soil Remediation Techniques for Military Explosive and Weapons Contaminated Sites . Geoengineer.

Bean-Mortinson, Jason, Annalise Duerr-Miller, Julia Vieau. (2009, April 21). Nisqually and Fort Lewis. Nisqually Watershed Podcasts, Conceptualizing Native Place program, The Evergreen State College, Olympia WA.

Jenkins, T. F., J. C. Pennington, T. A. Ranney et al. (2001). Characterization of explosives contamination at military firing ranges. US Army Corps of Engineers Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC) TR-01-05. Hanover, NH: US Army Engineer Research and Development Center.

Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM). (n.d.). Army Compatible Use Buffer (ACUB). Army.mil.

Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM). (n.d.). Fish and Wildlife. Public Works – Environmental Division. Army.mil.

Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM). (n.d.). Forestry Branch. Army.mil.

Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM). (n.d.). Public Works – Environmental Division. Army.mil.

Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM). (n.d.). UXO Awareness. Army.mil.

Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM). (n.d.). Wildland Fire. Army.mil.

Lustgarten, Abrahm. (2017, December 18). The Bomb That Went Off Twice: The explosive compound RDX helped make America a superpower. Now, it’s poisoning the nation’s water and soil. ProPublica.

Nazaryan, Alexander. (2014, July 17). The U.S. Department of Defense Is One of the World’s Biggest Polluters. Newsweek.

Packer, Bonnie. (2004, April). UXO Corrosion – Potential Contamination Source. Final Report, U.S. Army Environmental Command ER-1226. Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP)

Pichtel, John. (2012). Distribution and Fate of Military Explosives and Propellants in Soil: A Review. Applied and Environmental Soil Science. Article ID 617236.

Price, Jay. (2016, September 15). Military Bases Serve As Safe Haven For Endangered Species. National Public Radio.

Sharma P, Mayes MA, Tang G. (2013, August). Role of soil organic carbon and colloids in sorption and transport of TNT, RDX and HMX in training range soils. Chemosphere 92(8): 993-1000.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). (2012, January). Site Characterization for Munitions Constituents. Solid Waste and Emergency Response. EPA Federal Facilities Forum Issue Paper 505-S-11-001.

Washington Fish and Wildlife Office (WFWO). (n.d.). Federally Protected Subspecies of Mazama Pocket Gopher in Washington. FWS.gov.

Washington Fish and Wildlife Office (WFWO). (n.d.). Streaked Horned Lark. FWS.gov.

Washington Fish and Wildlife Office (WFWO). (n.d.). Taylor’s Checkerspot Butterfly. FWS.gov

Wilkinson, Charles. (2000). Messages from Frank’s Landing: A Story of Salmon, Treaties, and the Indian Way. Seattle: University of Washington Press.