John Lace

Republished in Works in Progress (1/1/20)

The Olympic Peninsula is a verdant mountainous region on the Washington coast. Lush rainforests brimming with old-growth trees sprawl forth to the sea from the slopes of the Olympic Range. It is truly a place of majestic beauty and untouched Pacific Northwest wilderness. Over a thousand square miles of this wild earth have been saved from clear-cutting and other development due to the creation of Olympic National Park, which has provided people from around the world access to this unique natural location for decades.

The U.S. military has also taken a renewed interest in the Olympic Peninsula and its lush forests. The U.S. Navy plans to conduct war games over the Peninsula, using Growler jets to simulate electromagnetic warfare. Many residents and visitors feel that these exercises threaten local ecosystems and communities on the Olympic Peninsula, and that they set a dangerous precedent for military exploitation of public places.

EMR Warfare Training on the Olympic Peninsula

The U.S. Navy stated in its Information Dominance Roadmap 2013-2028 that it seeks to “employ integrated information in warfare by expanding the use of advanced electronic warfare” (U.S. Navy 2013, II). The Navy’s desire to expand its advanced capabilities require training grounds that mirror battlegrounds overseas (U.S. Navy 2013, 12). The dense forests of Olympic National Park provide an ideal environment for testing electromagnetic radiation weaponry. These war games are meant to train Growler pilots in the use of radar jamming technology in an environment that reflects real-world combat situations (Jamail 2014, 2).

This training aims to disrupt an adversary’s ability to recognize and respond to the movement of U.S. personnel and war equipment (U.S. Navy 2013, 7). Locating and disrupting these communication systems requires a remarkable level of precision. Captain Scott Farr, who oversees the entirety of the Navy’s Growler fleet, said that “It takes a lot of complex training to develop that skill” (EarthFixMedia 2017). When the U.S. Navy was training pilots in the use of EMR weaponry on Whidbey Island, it found that a single test site on base did not provide a complex enough environment for the training to be truly beneficial for the pilots. In Farr’s words: “if you take a test and know where the answers are the whole time, it doesn’t make for a very difficult test” (EarthFixMedia 2017).

The proposed training would park large trucks equipped with EMR emitters throughout the Peninsula to generate electromagnetic radiation that the Growlers could then lock onto in order to simulate the act of jamming enemy communication systems (Kiley 2014, 1). The mobility of the trucks would make the targeting of their communication systems more difficult and therefore more effective as an exercise. In a written statement, Navy Region Northwest spokeswoman Sheila Murray said that “the transmitter trucks will provide better quality training for aircrews before they deploy and potentially have to operate in harm’s way” (Ashton 2016, 4).

Ramifications of War Games on the Peninsula

The adverse effects of such war games on the Olympic Peninsula come in forms both blatant and subtle. The U.S. Navy’s use of the Olympic Peninsula comes on the heels of a variety of other attempts by the United States military to conduct war games outside the boundaries of military installations (Hammond 1997, 974). These military exercises have a history of negatively impacting local ecosystems and alienating nonmilitary personal from public areas (Sierra Club 2017). The noisy Growler jets that prowl above Olympic National Park have proven a nuisance to communities that live under their omnipresent din (See Noise Issues). Beyond the jets themselves, the electromagnetic gear that the Navy employs in these exercises come with a laundry list of potential hazards.

Perhaps the main ramification of these games is the precedent it sets for the military to peer over its fences for locations to practice war. The 1807 Posse Comitatus Act limits the Army’s ability to operate within the public sphere. Under its protection, common people should not be harassed by the military presence within United States borders (Hammond 1997, 953-968). But the military’s coffers are burgeoning, its conflict are unending, and its advanced forms of weaponry require vast stretches of airspace and diverse terrains for practice. The truth is war has been coming home for years (Hammond 1997, 976). The militarization of domestic police forces and the expansion of domestic surveillance are both side effects of current U.S. campaigns abroad. Public lands are under constant threat by these same tendrils of U.S. military largesse.

U.S. Military’s History of Encroachment on Public Lands

Recently, the whole point of public lands has come into question. Conservative politicians have long attempted to transfer public lands in the West to private entities for mining, drilling, ranching, and logging. There has been a pattern in recent years of leaders, in both federal and state governments, shrinking monuments and parks for the purposes of extraction and desecration (Ingram 2018, 2). Conservationists have long warned of the danger posed to natural places by privatization, but not as many are mobilized to defend against the expansion of the U.S. military apparatus into public lands. Several branches of the armed forces have been pushing to practice drills in public places and the expansion of U.S. military power will ensure that this practice will only increase.

In most cases, wherever the military goes, the public cannot follow. The Department of Defense owns more than 11 million acres of land in the United States, and unlike other federally controlled lands, the military does not share its domain with the public (Vincent 2017, 6). The Pentagon’s desire for large swaths of U.S. territory for military drills is only expanding and the security apparatuses that encircle military-held land is becoming more advanced and restrictive to surrounding communities.

One does not have to look far inland to find examples of the United States military encroaching upon lands that were not designated for their use. On the eve of World War I, the creation of Fort Lewis absorbed more than three thousand acres of the nearby Nisqually Tribe’s Reservation ( See Displacement of the Nisqually Tribe). The proliferation of bases across the United States in the 20th century saw the annexing of great swaths of land where U.S. citizens and Indigenous nations have dwelled.

Risks to the Peninsula

Crash Risks

The Navy has a sordid history of damaging ecosystems with its war games. The crashing of military vehicles happens all too frequently and the tainting of local sources of water is almost inevitable due to the wasteful and messy nature of military drills (See Water Contamination on Whidbey Island). The Olympic Peninsula does not face the same threats as Whidbey Island when it comes to groundwater pollution, but the presence of noise pollution by Growler jets is similar. The Navy’s environmental impact report did not take into account the prospect of crashing a jet into the Olympic Peninsula (U.S. Forest Service 2015). Olympic National Park hosts a variety of delicate ecosystems that could face irreparable damage if an accident occurred. In September 2018, a small aircraft crashed in a mountain south of Reno, Nevada and started a forest fire that spread to 20 acres almost immediately (Associated Press 2018). These Growler flights could pose a threat to local communities and the rare grooves of old-growth trees that can be found exclusively on the Peninsula.

Risks to Human Health

Beyond the possibility of a crash, the noise pollution produced during this training would harm local populations (Sierra Club 2017, 7). Growler jets are the loudest in the world, and a great deal of research details the negative health effects of jet noise on exposed populations. Higher rates of hypertension and heart attacks have been reported among those exposed to high levels of aircraft noise (Dahlgren 2017, 5). Studies have linked high levels of noise with developmental issues among children. The adverse effects on children exposed to chronic noise exposure include “elevations in resting blood pressure, attention deficiencies… deficits in reading… diminished task motivation, poorer memory when high information processing demands are present, and deficits in infant cognitive development” (Dahlgren 2017, 13-14). There was no mention of the sonic effects of these Growler flights on local populations in the U.S. Navy’s Environmental Impact Report.

There is a great deal of ongoing research into the adverse effects of electromagnetic radiation. A plurality of these studies confirm the fears of those who live throughout potential training grounds, that electromagnetic radiation can be hazardous to human and animal health (Zamanian 2005, 26).

Human exposure to electromagnetic radiation can “vary from no effect at all to death, and can cause diseases such as leukemia or bone, breast, and lung cancer” (Zamanian 2005, 26). The journal Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy released a study that concluded that “a reasonable suspicion of risk exists based on clear evidence of bioeffects at environmental relevant levels, which, with prolonged exposures may reasonably be presumed to result in health impacts” (Hardell 2008, 1).

The Navy claims in its 2015 Environmental Assessment that its use of EMR weaponry will have no effect on the people of the Peninsula (U.S. Forest Service 2015, 5). This claim is not supported by a swath of studies that confirm the detrimental effects of electromagnetic radiation on human health (Jamail 2014, 3).

The EarthFix Media documentary Battle Ready: The Military’s Environmental Legacy in the Northwest, shown by Oregon Public Broadcasting, includes a section (at 37:18) about the Growler jet controversies on the Olympic Peninsula.

Risks to Wildlife Health

Noise pollution produced by Growlers could also negatively affect local wildlife. Chronic noise disrupts the ability of animals’ to detect sounds essential for breeding and habitation. These noises are no mere nuisance to local fauna, they can be seen as a threat and can disrupt the regular habits of birds and mammals. Studies have shown that this intrusion of chronic high-decibel sound overstimulates animal nervous systems, leading to instances of chronic stress, diminished attention to young, increased risk of abandonment of young, habitat avoidance, diminished energy levels, and decreased life spans of subjected species (Radle 2007).

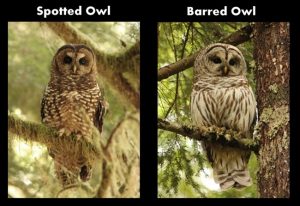

The Olympic Peninsula is part of the Pacific Flyway, “which makes it a critical pathway for migratory birds, with an estimated 1 billion birds migrating along the flyway annually” (Jamail 2014, 7). Electromagnetic radiation can interfere with bird migratory patterns by dampening their ability to lock on to the pull of the magnetic poles. The amount of electromagnetic radiation that causes birds to lose their bearings is far lower than “the lowest exposure limits recommended for humans” (Hsu 2014, 1). One of the key issues with EMR training in this region is that the disruption of migratory patterns can have detrimental effects on ecosystems not only within the Peninsula, but beyond as well. The effects of electromagnetic radiation on migrating birds was not mentioned in the U.S. Navy’s Environmental Assessment (U.S. Forest Service 2015). There is still a good deal of research required to fully understand the impact of EMR war games on local people and animals.

Peninsula Residents Respond to War Games

Local communities have had to deal with a great deal of secrecy from the U.S. Navy when it comes to its war games. The Navy has provided next to no public forums for local people to ask questions about the war games, a practice that is required by law (Jamail 2014, 2). The Environmental Impact Reports have been incomplete, and the Navy has refused to follow proper protocol when it comes to releasing public notices (U.S. Forest Service 2015, 1-228). These tactics of the military have not been well received by many Peninsula residents.

Local Communities’ Perspectives

Lina Sutton, a retired teacher in Port Townsend, said in an interview with Truthout that “most of the people who live here do so because we are free of this kind of militarism. And people who visit here, come here for the natural beauty and environment, and if we allow this place to be turned into a war-gaming area, it is reprehensible” (Jamail 2014, 3). Most interviews of Peninsula residents follow a similar vein, but the logic behind their indignation varies.

In October 2016, protesters presented to the Forest Service an online petition “with more than 110,000 signatures” in opposition to Navy’s plans to conduct war games over the Peninsula (Ashton 2016, 2). Local opinions on militarism shift on a person-to-person basis, but there appears to be a near-unanimous negative response to the potential of noise pollution and environmental degradation brought on by EMR warfare training (Ashton 2016, 2). Several local activist groups have formed to try and curb the expansion of war games onto the peninsula. One of these groups is called the West Coast Action Alliance (WCAA), which claims that it is “part of a small cadre of people who for years have been doing the tedious detective work of analyzing the Navy’s thousand-page Environmental Impact Statements and Environmental Assessments, all of which claim none of the Navy’s extraordinarily loud and disturbing activities in our region will have any ‘significant impacts’ on wildlife, habitat, our communities, our drinking water, or our economies” (WCAA 2018, 1). The WCAA’s mission is shared by several other groups who have formed to oppose the expansion of military exercises into the domestic spaces (Ashton 2016, 3).

Another notable activist group is the Sound Defense Alliance, which is composed of a wide range of civilian and political entities from the Olympic Peninsula and Whidbey Island. Its aim is to “provide transparency and a voice for dialog and negotiation between citizens, local governments, military installations, state agencies, federal agencies, and our elected leaders to better coordinate a balanced approach as military decisions are being considered in Washington State” (Sound Defense Alliance 2018). The South Sound Alliance is a coalition of different anti-militarization groups that oppose Growler flights over the Olympic Peninsula and Whidbey Island. The people involved in this alliance come from a variety of different backgrounds, but they are united in their opposition to the Navy’s proposed war games, and through this unity their voices are amplified. These groups showcase the determination of local populations in preserving places of beauty, ecological importance, and cultural significance.

Indigenous Perspectives

A Lower Elwha Klallam artist named Linda said in a video interview for Olympic Peninsula Watch, “I’d rather listen to the beach. I would rather listen to the birds… Shooting all this radiation into our environment. I don’t want it here, and I don’t think anyone else does” (Olympic Peninsula Watch 2015).

The trust relationship of Native nations on the Peninsula with the federal Government is complicated. Cooperation between tribal governing bodies and the military is often a very one-sided affair, wherein tribes are forced to go on the defensive when the military encroaches into their lands and airspace. The U.S. military often treats Indigenous nations as subordinate entities which are undeserving of self-determination. This dynamic can make it difficult for Indigenous nations to draw hard lines, as the U.S. military has a history of denying Indigenous peoples their right to self-govern and enforce what happens within their reservations and treaty territories.

The response of the Quinault Indian Nation to the Navy’s plan to use electrical magnetic weaponry within 10 miles of their reservation was interesting. A statement from President Fawn Sharp of the Quinault Indian Nation was sent to Truthout regarding the Navy’s war games, it reads:

The Quinault Indian Nation has spoken with the Navy regarding the electronic warfare range proposal due to our ongoing concerns for our people and our wildlife in our usual and accustomed hunting grounds. Our people have lived here for thousands of years. We have always depended upon the fishing, hunting and gathering resources here, and managed these resources for the benefit of current and future generations. Today we co-manage these resources with our fellow sovereigns, the state and federal governments. The Navy has responded to our questions, on a government-to-government basis. At this time our only additional comment is that we will be monitoring the Navy’s activities, to assure there is no harm to the resources we manage and must protect for the sake of our people, our heritage and our generations to come (Jamail 2014, 2).

This response is very diplomatic and it remains unclear if the U.S. Navy shares the same level of respect for the Quinault’s ancestral claims on the land as the Quinault appear to have for the U.S. government as a fellow sovereign. Indigenous modes of living and kinship have long conflicted with the operations of the U.S. military. The history of this interaction is a bloody one, and there is little to indicate that the U.S. military has come very far in their respect for the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Coast.

Conclusion

The Olympic Peninsula is a unique and cherished place to Washington residents and visitors. It is home to a variety of rare ecosystems that are not found anywhere else on Earth, and its preservation is of the utmost importance to those who dwell there. The Navy’s planned EMR war games could threaten many forms of life on the Peninsula, often in ways that are not readily apparent. The Navy’s encroachment onto the Peninsula is part of a wider expansion by the U.S. military onto public lands throughout the United States. It is important to pay close attention to these developments because this expansion threatens not only the Peninsula’s ecosystems, but the foundations of American civic life as well.

Sources

Associated Press. (2017, September 18). Group sues over Navy’s plans for training in Olympic National Forest. The Navy Times.

Associated Press. (2018, September 2). Small plane crashes near Reno, ingnites mountain wildfire. FOX News.

Ashton, Adam. (2016, February 18). The Army, Navy forge ahead with training plans for Northwest forests despite loud opposition. Bellingham Herald.

Bernton, Hal. (2016, November 29). Expanded Growler jet war training over Olympic Peninsula gets a draft OK. Seattle Times.

Dahlgren, James. (2017, February 16). Combat Jet Noise from Landing and Taking Off At Whidbey Island-OLF Coupeville Is Permanently Injuring The Exposed Population 2017. American Board of Internal Medicine.

EarthFixMedia. (2017, March 10). Battle Ready: The Military’s Environmental Legacy in the Northwest. Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Hammond, Matthew. (1997, January 21). The Posse Comitatus Act: A Principle in Need of Renewal. Washington University Law Review.

Hardell, L. (2008, February 6). Biological Effects from Electromagnetic Field Exposure and Public Exposure Standards. Journal of Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy.

Ingram, Mrill. (2018, June 26). What’s Wrong with Privatizing Public Lands. The Progressive.

Jamail, Dahr. (2014, November 10). Navy Plans Electromagnetic War Games Over National Park and Forest in Washington State. Truthout.

Jamail, Dahr. (2015, November 16). Navy Expands Domestic War games, Despite Public Concern Over Alleged Illegalities. Truthout.

Jamail, Dahr. (2016, May 9). Exclusive: Emails Reveal Navy’s Intent to Break Law, Threatening Endangered Wildlife. Truthout.

Kiley, Brendan. (2014, December 15). Navy Wants Permission for Electromagnetic War Games Over Olympic National Park. The Stranger.

Olympic Peninsula Watch. (2015, June 18). The Olympic Peninsula Is Not For Electromagnetic Warfare Training. Olympic Peninsula Watch.

Radle, Autumn, (2007, March 2). The Effect of Noise On Wildlife: A Literature Review. University of Oregon.

Save the Olympic Peninsula. (2019). Save the Olympic Peninsula.

Sierra Club. (2017, August 22). Navy Warfare Training on the Olympic Peninsula. Sierra Club.

Sound Defense Alliance. (2018, January 28). About the Alliance. Sound Defense Alliance.

U.S. Forest Service. (2015, July 27). Pacific Northwest Electronic Warfare Range Environmental Assessment. U.S. Forest Service.

U.S. Navy. (2013, March). Information Dominance Roadmap 2013-2028. Defense Innovation Market Place.

Vincent, Carol. (2017, March 3). Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data. Congressional Research Service.

West Coast Action Alliance. (2018, September 10). WCAA Web Site Destroyed + Intimidation. WCAA.

Winger, Kara. (2018, February 21). Olympic National Park is no place for Growler Jets. Seattle Times.

Zamanian, Ali. (2005, July 2). Electromagnetic Radiation and Human Health: A Review of Sources and Effects. Summit Technical Media.