Matthew Neisius

In 1954, Congress passed the Atomic Energy Act that encouraged the commercial development of nuclear power in the United States (Eureka County Nevada). Nuclear power plants produce radioactive waste that requires long-term storage and disposal. After much study and debate, a disposal site at Yucca Mountain in southwestern Nevada was selected which is on Western Shoshone treaty land. For many years, the Western Shoshone and many activists fought against making Yucca Mountain into a high-level nuclear waste site. They opposed this project on both cultural and scientific grounds and as an example of environmental racism.

The Western Shoshone Nation has demonstrated much resilience over the years as it continues to fight against this project (Lojowsky). As a result of these and related efforts, the Obama Administration abandoned work on the Yucca Mountain repository in 2009 (Macalester College). However, there are concerns that the Trump Administration and Congress will restart the work, so additional resistance efforts on the part of the Western Shoshone Nation and others will likely be needed.

What is Nuclear Waste?

Nuclear waste is generated from a various sources. “The majority originates as spent fuel from commercial nuclear reactors: pellets of uranium that have exhausted their energy potential over three or four years of use and have come to consist of a mixture of extremely dangerous chemicals, including plutonium” (Macalester College). Other sources include medical equipment and the military. This paper will focus on the primary source of nuclear waste from commercial nuclear power plants. The fuel for these plants is created by enriching the mineral commodity uranium and processing into pellets about an inch long (see illustration below) which are highly radioactive.

As these pellets exhaust their energy potential after a few years and power plants are retired, the nuclear material remains and requires disposal. Disposal is the responsibility of the federal government as specified in the same 1954 law noted above. Nuclear waste can remain highly radioactive for thousands of years so storage and disposal is both difficult and controversial (Macalester College). At the present time, nuclear waste is stored on-site in temporary facilities at various nuclear plants and research facilities throughout the U.S.

History of Yucca Mountain Project

The Yucca Mountain project began in 1982 when Congress passed the Nuclear Waste Policy Act. It required “the establishment of a deep geologic repository for nuclear waste storage and isolation . . . Two repositories are to be developed, one on each side of the country, to ensure regional equity . . . In 1982, the Department of Energy selected nine locations in six states for consideration” (Lander County Nevada).

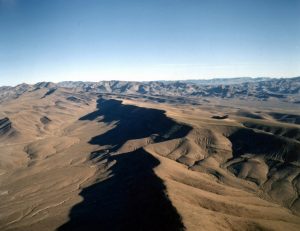

In 1986, the list was narrowed to three sites in the Western U.S. – Hanford in eastern Washington State, a site in the Texas panhandle southwest of Amarillo, and Yucca Mountain in southwestern Nevada about 80 miles north of Las Vegas (see photo below).

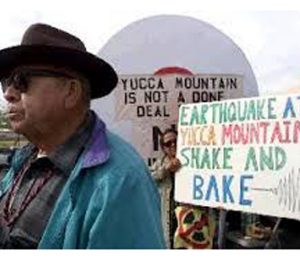

After intense lobbying and much discussion, Congress suspended the repository selection process in 1987 and designated Yucca Mountain as the only site to be considered. In 2002, President Bush signed a law approving the repository at Yucca Mountain (Lander County Nevada, 2014). Since that decision, there have been numerous lawsuits and actions by various parties that both supported and opposed the project. The project was supported by the nuclear energy industry and many of the states that wanted to eliminate the temporary waste storage locations and provide better security.

As noted above, Yucca Mountain is on Western Shoshone treaty land and the Western Shoshone Nation was very active in opposing the project. There was also opposition by the scientific and environmental communities. (Hargreaves, 2011) As a result of these efforts, the Obama Administration suspended work on the Yucca Mountain repository in 2009.

Waste Repository Pros and Cons

Over the years, many arguments have been made for and against the use of Yucca Mountain as a nuclear waste repository. The following summarizes the major reasons given by supporters of the project (Hargreaves).

• 65,000 tons of contaminated waste is located at nuclear power plants near major U.S. cities.

• “Carbon free-electricity” is vital in the fight against climate change.

• Yucca Mountain is an ideal location for nuclear waste repository, since it is in a desert. It is located at the corner of three areas of federal property, including an Air Force gunnery range.

• The site is not susceptible to earthquakes, and the volcanoes nearby are not an issue.

• The government has put time, money and effort into the site that should not be wasted.

There have also been many arguments opposing the Yucca site which are summarized below:

• There could be gaseous emissions from radioactive waste, since rock fractures allow gas to move up and out of the mountain.

• Transporting the waste could result in spills.

• “From 1976 to 1996, more than 600 earthquakes measured over 2.5 on the Richter scale within 50 miles of Yucca Mountain” (Olson).

• The chemistry of rocks is salty. Waste containers will be made of iron-nickel alloy and when put together there would be accelerated chemical reactions which could result in the corrosion of the containers (Olson).

Yucca Mountain and Western Shoshone Culture

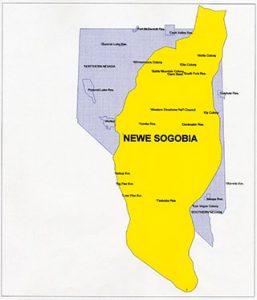

Western Shoshone objections to the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste project are related to both history and culture. Like other Indigenous people, the people of the Western Shoshone Nation have strong cultural ties to their land. “To the Western Shoshone people Yucca Mountain is part of a seamless scared landscape known in the Shoshone language as Newe Sogobia . . . Cultural identity is obtained from living in a place that provides a sense of identity binding the Western Shoshone people to the land” (Zabarte).

The map below shows the original boundaries of the Western Shoshone ancestral land:

In the traditions of the Western Shoshone, the disciplines of astronomy, religion, medicine, agriculture and governance blend together to form a place-based identity that existed in harmony with the land for many generations (Western Shoshone National Council).

The first recorded Shoshone contact with non-Native people was in 1680 when the Spanish invaded the area. After 250 years of warfare, the Western Shoshone Nation signed the Treaty of Ruby Valley with the U.S. government in 1863. The Western Shoshone agreed to let settlers travel across their land and the U.S. government agreed to pay for this access. Unlike other treaties, no land was ceded to the government. But as with all Indigenous treaties, the treaty terms were widely ignored. Over time, much of the traditional Western Shoshone land was taken over by the government for military use, nuclear testing, and white settlement (Solnit).

The Yucca Mountain project was a direct threat to the Western Shoshone culture and beliefs:

Land and its proper use and care dominated discussions with people about the Yucca Mountain project . . . There is consensus that putting nuclear waste into the earth violates the traditional Shoshone teachings and will disturb the natural balance and bring harmful consequences. It is viewed as particularly harmful to water, plants, and animals, but also people (Fowler).

Although the actual site for the proposed waste repository is limited in size and mostly underground, the Western Shoshone consider the entire Yucca Mountain area and surrounding lands in the Great Basin to be part of a larger whole. They have lived in this area for hundreds of years and it is closely linked to their cultural identity. The Western Shoshone believe that the nuclear waste project will negatively impact their lives and destroy important cultural resources that cannot be replaced (Stoffle, Richard; et.al).

Impact of Colonialism, Racism, and Framing

Many of the opponents of the project believe that there were several indirect forces at work that influenced the selection of Yucca Mountain as a waste repository. One of these forces was the impact of colonialism that was noted by Dorceta Taylor in her book Toxic Communities. Evidence of colonialism usually includes:

(1) Forced entry of one country into the territory of another country, (2) alteration and destruction of the indigenous cultures and patterns of social organization of the invaded country, (3) domination of indigenous peoples by the invaders, and (4) the development of elaborate justifications for the invasion and subsequent behavior of the invaders (Taylor).

In reviewing the history of the Western Shoshone Nation, all of the above factors were present in some form as the U.S. government occupied Western Shoshone lands.

Taylor goes on to argue that Native Americans were targeted for this form of internal colonialism because their land was often in isolated areas and they had little political power. As a result, toxic waste (i.e. nuclear waste in the Western Shoshone case) was often dumped on Indigenous land (Taylor).

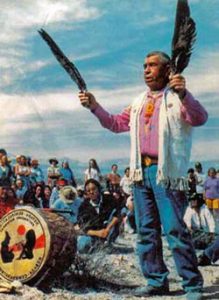

Corbin Harney, a Western Shoshone spiritual leader and early environmental activist, spoke about this as part of his contribution to an oral history project sponsored by the University of Nevada, Las Vegas:

And why did they choose a place like Yucca Mountain to bury this nuclear rot? The only thing that we talk about . . . was . . . because they said, you’re a ward of the government. We’re going to take care of your land for you under trust. And that’s the reason why . . . they chose Indian land throughout the country to do whatever bad thing they wanted to do (Harney).

Western Shoshone activists have also argued that environmental racism was a factor in the decision to select Yucca Mountain. As explained by Ian Zabarte, a Western Shoshone activist and board member of the Native Community Action Council:

From our perspective the processes employed by the DOE is environmental racism designed to systematically dismantle the living lifeways of the Western Shoshone people in relation to our land . . . It’s not about the amount of radioactivity that would permeate the groundwater . . . The environmental racism lies in the very notion that it would be okay to put any radioactive material there at all (Indian Country Today Media Network).

There concerns were also noted by Ojibwe community organizer Winona LaDuke in her book All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life:

The federal government is proposing to use Yucca Mountain, sacred to the Shoshone, as a dumpsite for the nation’s high-level nuclear waste. Over the last 45 years, there have been 1,000 atomic explosions on Western Shoshone land in Nevada, making the Western Shoshone the most bombed nation on Earth (LaDuke).

The selection of the Yucca Mountain site was probably also influenced by framing, which is a concept from psychology which suggests that people react and make choices depending on how the issue is presented. The decision about the selection of a nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain was widely covered by the media. An analysis of this media coverage at the time indicated a strong preference for describing Yucca Mountain in very abstract terms using pronuclear, Cold War language. The more sacred aspects of the mountain that were important to the Western Shoshone Nation were almost imperceptible [in the coverage] (Brock).

To illustrate this point, the following are examples of descriptions of Yucca Mountain used by the media when reporting on the nuclear waste project (Brock).

• Barren-seeming place; hellishly dry desert ridge (Washington Post)

• Desolate; remote (North Jersey Media Group)

• Volcanic heap; final resting place (Knight-Ridder)

• Remote ridge; desolate ridge (St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

• Ugly mountain ridge; nondescript ridge (Washington Post)

• Desolate mountain ridge (Media News Group)

• Desolate, barren, or remote ridge (New York Times)

• Ancient volcanic ridge; arid ridge (Associated Press)

The impact of colonialism, environmental racism and framing on the Yucca Mountain selection cannot be measured specifically, but indirect evidence suggests that each was a factor in the final decision.

Western Shoshone Activism and Resilience

One of the most important elements of a successful resistance movement is to remain vigilant over a long period of time. As noted by Earth First!:

It is important to remember that there are no victories in our work – only temporary truces. The nuclear industry was in many ways contained by the hard, consistent work and sacrifice of activists who came before us . . . We need to draw attention to the facts of nuclear power. We need to form alliances with the groups, especially the Indigenous groups, who are struggling against this menace (Lojowsky).

The Western Shoshone Nation has shown this type of resilience in being able to stay focused on the nuclear waste issue over many years, despite barriers and obstacles. As Winona LaDuke noted in her book All Our Relations, “Grassroots and land-based struggles characterize most of Native environmentalism. . . Our commitment and tenacity spring from our deep connection to the land. This relationship to land and water is continuously reaffirmed through prayer, deed, and our way of behaving” (LaDuke). These efforts have been possible because of the Western Shoshone’s strong connection to the land and their ability to pass on their values and beliefs to future generations.

The efforts of the Western Shoshone Nation to oppose the Yucca Mountain site are also part of the broader environmental justice movement underway throughout the world. “Environmental justice calls for universal protection from extraction, production, and disposal of toxic/ hazardous wastes and poisons that threaten the fundamental right to political, economic, cultural, and environmental self-determination of all peoples” (Reed).

Bernice Lalo, a Western Shoshone elder from the Battle Mountain area of Nevada, was an early supporter of the movement:

Environmental injustice is just tearing into the land. Leaving a real death heritage of the people who are coming behind us. . . I don’t think we will ever get the federal government to compensate us for punitive damages, I don’t see that happening. When you pretend that our people don’t exist, you don’t have to justify providing any economic . . . punitive damages to them . . .That’s what I feel as a Shoshone person (Houston).

In developing their resistance movement, the Western Shoshone Nation utilized a number of successful mobilization tactics. These tactics included creating alternative knowledge and proposals; involving national and international organizations (see below); use of lawsuits and court cases; media activism, public campaigns and protest marches (Environmental Justice Atlas). As a result of these tactics, the Western Shoshone Nation has been able to forge alliances with environmental and other groups and build support for the Yucca Mountain resistance movement.

The Western Shoshone Nation has also understood the importance of keeping this issue visible to larger audiences. It achieved an important victory in 2006 when the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination issued a final report to the U.N. General Assembly. This report recommended, among other things, that the U.S. government respect the rights of the Western Shoshone people and respect the spiritual and cultural significance of their ancestral lands. The report also recommended that the U.S. government involve the Western Shoshone in the discussions about use of their lands and that any solutions be acceptable to them (United Nations General Assembly). Although these recommendations did not have the force of law in the U.S., gaining international support for their resistance efforts was an important milestone for the Western Shoshone.

Another important victory was included in the recommendations of President Obama’s Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future which were issued in 2012. The recommendations included the use of a consent-based strategy for storing nuclear waste and a much longer timeframe developing what are likely to be multiple sites around the country (U.S. Department of Energy). The Commission’s recommendations were significant because they required the Western Shoshone Nation to be involved and agree with nuclear storage solutions and also re-introduced the idea of multiple sites rather than consolidating all the waste in Nevada at Yucca Mountain.

The issue of Yucca Mountain is likely to resurface in 2017 if the Republican Congress and/or the Trump Administration request funding to proceed with the site work or do additional studies (Martin).

Conclusion

For many years, the Western Shoshone and many activists fought against making Yucca Mountain into a nuclear waste site. They opposed this project on both cultural and scientific grounds and as a form of environmental racism. The efforts of the Western Shoshone Nation to oppose the Yucca Mountain site are part of the broader environmental justice movement underway throughout the world. In developing their resistance movement, the Western Shoshone Nation have utilized a number of successful mobilization tactics. The resilience of the Western Shoshone Nation will continue to be tested as the nuclear industry and the government look for solutions to the nation’s nuclear waste problem in the years ahead.

Media Coverage

The Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository was extensively covered over the years as the selection process proceeded. After President Obama suspended the project in 2009, media coverage decreased. However, reporting has recently increased again with the election of Donald Trump and the Republican Congress which may provide funding to restart the project development work. From December 2016 through February 2017, Yucca Mountain was covered by several national media outlets (e.g. Bloomberg, the Associated Press, New York Times, USA Today, Forbes); by local newspapers (Las Vegas Review-Journal, Las Vegas Sun); by several national journals (Environment & Energy News, Physics Today) and other local and national media outlets. The Nevada Congressional delegation also published a press release on this topic. Most of this reporting was fact-based and quoted or referenced outside sources with an interest or expertise in this topic. Many of the stories also included opinions of the authors or others, generally with negative views about re-opening Yucca Mountain for additional study or preparation to receive nuclear waste. As might be expected, these negative viewpoints were most often expressed by publications and interested parties in Nevada.

Sources

Brock, T. A. (2005, October). Great Basin Imagery in Newspaper Coverage of Yucca Mountain. The Geographical Review, pp. 517-36.

Environmental Justice Atlas. (2016, April 1). Yucca Mountain nuclear waste storage, USA. Environmental Justice Atlas .

Eureka County Nevada. (2016, January 4). Timeline: 1954-2014. Eureka County, Nevada- Nuclear Waste Office.

Fowler, C. (1991, October). Native Americans and Yucca Mountain. State of Nevada.

Hargreaves, S. (2011, July 11). Nuclear Waste: Back to Yucca Mountain? CNN Money.

Harney, C. (2005, August 4). The Nevada Test Site Oral History Project. (S. Becker, & M. Palevsky, Interviewers)

Houston, D. M. (2007). Topographies of Memory and Power: Environmental Politics, History, and Justice at Yucca Mountain, Nevada. Ann Arbor, MI: Proquest Information & Learning Company.

Indian Country Today Media Network. (2015, September 29). Environmental Racism Behind Plan to Store Nuke Waste Under Yucca Mountain: Tribes. Indian Country Today Media Network.

LaDuke, W. (1999). All our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

Lander County Nevada. (2014). History of Yucca Mountain Project. Lander County Nevada Oversight Program.

Lojowsky, M. (2010, January). The Nuclear Renaissance & the Necessary Resistance. Earth First!

Macalester College. (2010, May 1). The Yucca Mountain Nuclear Controversy. Macalester College Environmental Studies.

Martin, G. (2017, January 19). Trump’s pick for Energy chief says Yucca Mountain can’t be ruled out. Las Vegas Review Journal.

Olson, M. (2014, December). Why Yucca Mountain would fail as a Nuclear Waste Repository. Nuclear Information and Resource Service.

Reed, T. (2017). Toxic Colonialism, Environmental Justice, and Native Resistance in Silko’s Almanac of the Dead. Oxford Journal, 25-39.

Solnit, R. (1994). Savage Dreams. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Stoffle, Richard; et.al. (1990). Native American Cultural Resource Studies at Yucca Mountain. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Taylor, D. (2014). Toxic Communities. New York, NY: New York University Press.

U.S. Department of Energy. (2012, January 6). Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future. U.S. Department of Energy.

United Nations General Assembly. (2006, August 8). Report of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. United Nations General Assembly.

Western Shoshone National Council. (2017, January 29). How to Kill a Nation. Western Shoshone National Council.

Zabarte, I. (2010, November 23). A Western Shoshone Perspective on Yucca Mountain. Native American Netroots.