Thomas Clark

In the vast majestic state of Montana, natural resource extraction holds a central place in history. Posed by most of the state’s population as an economically beneficial aspect of capitalist engagement, resource extraction has played a consistently significant economic role in most Montana communities. From Billings to Butte, Helena to Libby, citizens across Montana have welcomed resource extraction projects into their communities. The problem is, with these projects come corrupt corporations with the sole intent of financial gain, leaving environmental and social negative externalities behind after the resources have been efficiently extracted.

For more than a century, resource extraction companies have preyed on economically vulnerable communities in Montana, using the desperation of the community against itself. In doing so, these corporations have been able to take advantage of loose legislation and minimal taxation and have exhibited complete disregard for any environmental damages. Throughout the United States, resource extraction corporations have fed on social unrest, using ideological and racial divisions to quell protests, dissolve unions, and utilize essentially transparent environmental racism. Yet in Montana today. citizens have had enough. Today, resource rebels throughout the state are standing together and fighting against corrupt extraction capitalists.

History of Resource Extraction In Montana

Initially integrated into the United States as a territory, due to massive gold rushes in western North America, Montana remained an afterthought for most East Coast Americans well into the nineteenth century. But as the nation’s economic reliance on natural resources continued to grow, Montana would become a state of great importance at the turn of the twentieth century, ballooning into a global copper capital. But in order to accurately conceptualize Montana’s financial rise into national relevance, one must gain a proper understanding of its territorial inception.

Any conversation about resource extraction in Montana has to begin in the state capital of Helena. While Anglo settlement in Montana began in 1862, the territory’s true founding can undoubtedly be traced back to 1864, when gold rushes began to bring tens of thousands of miners in search of gold. Despite the sheer numbers of extractors, Montana’s largest gold deposit almost went unnoticed. “In 1864, four prospectors spotted signs of gold in the Helena area while on their way to the Kootenai country, but they were eager to reach the reportedly rich gold regions farther to the north,” after striking out in the northern regions the miners returned to Helena in desperation. “When the signs turned out to mark a rich deposit of placer gold, they staked their claims and named the new mining district the Last Chance Gulch” (“City of Helena” 2016).

The discovery of the Last Chance Gulch would vault Helena into financial relevancy, joining the likes of Bannack and Virginia City as one of Montana’s lucrative mining towns. “Over the next four years, Last Chance Gulch produced $19 million worth of gold (approximately $221 million in today’s dollars)” (Egan, 104). After a few decades of glorious gold extraction, Helena was home to more millionaires per capita than anywhere in the world. By 1888, more than fifty millionaires called Helena home. But the gold veins would eventually run dry, and the town’s economy would drastically change. Yet, unlike many of the mining towns that would fall victim to Montana’s boom-and-bust economy, Helena would carve out a lasting place in Montana’s extractive history. Due to Helena’s location on several major transit avenues, abundance of agriculturally productive lands, and proximity to other mining districts, Helena would be named Montana’s territorial capital in 1877, and the state capital just over a decade later in 1889. Helena’s role changed from one of extraction to one of facilitation, as the town would become a key cog in Montana’s intricate mining network. One of Helena’s primary roles was assisting in the facilitation of Montana’s growing copper industry, primarily in the copper-rich town of Butte, Montana.

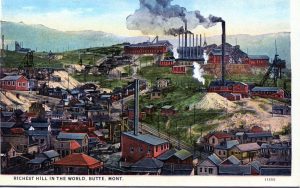

After Montana’s gold rush, the state rapidly gained notoriety as a vast landscape full of valuable minerals waiting to be extracted. From the seemingly endless silver supply in Bannack to the copper caves of Anaconda, Montana’s mining legacy began in flourishing fashion. Despite all the industrial extraction success stories across the state, no one could have ever anticipated the incomprehensible financial success of Butte’s “Richest Hill on Earth.” In fact, few prospectors envisioned the Butte hill as land with any mineral significance. In the 1860s Butte was scouted as a possible location for extensive gold mining endeavors, but after almost a decade of failed attempts to extract both gold and silver from the hill, the lone smelter in the greater Butte area was abandoned. For Butte, economic prosperity failed to arrive “until 1874 when there was a resurgence brought on by the relative closeness of the new Union Pacific Railroad” (“Mining History of Butte” 2001).

Much like Tacoma, Reno, or Billings, Butte’s economic viability was intrinsically tied to rail, as railroad accessibility lowered the cost of supplies while providing a cheaper avenue for shipping high grade ore. By the late 1870s Butte was in the midst of a mineral revival. Railway access led to extraction companies giving Butte’s hill a second look, and the results were robust. Large silver deposits were quickly discovered throughout Butte, and prestigious mining operators (such as the Walker Brothers of Salt Lake City) opened smelters on Butte’s historic hill.

When the Walker Brothers sent Marcus Daly to manage their silver mine, neither party had plans of expanding out of the silver business. But Daly immediately recognized a new industrious possibility in Butte: copper mining. Coinciding with the growth of electricity, Daly began mining copper in Butte. With other entrepreneurs doing the same, Butte quickly became the copper capital of the world, in “1882 the district produced nine million pounds of copper. In 1883 production leaped over 250%” (“Mining History of Butte” 2001). The unprecedented growth also meant unprecedented competition, as Daly was building his reputation as a mining mogul, others moved in looking for comparable riches.

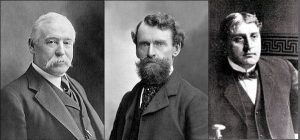

Two main competitors would join Daly in their pursuit for copper profits: William A. Clark, a banker from Red Lodge, and Fritz Augustus Heinze, a young mining engineer for both the Montana and Boston mining companies. Clark made a fortune off the failed investments of others, throughout his banking career in Red Lodge, consistently purchasing failed mining operations, for pennies on the dollar. Heinze had intricate knowledge of the mining industry and moved away from the Montana mining company to incorporate the Montana Ore Purchasing Company in 1893.

After a few lucrative decades in the industry, Clark, Daly, and Heinze distinguished themselves as the Copper Kings of Butte. For the next two decades, the three Copper Kings competed for the upper hand in the illustrious copper landscape of the Montana town, but by 1925 all three were dead. The Copper Kings died soon after relinquishing control of Butte’s mining industry to the Rockefeller family and its nationwide mining conglomerate Standard Oil. Butte’s mining industry, like its Copper Kings, would soon fall as well. The 20th century marked a stark contrast to the 19th for the town of Butte, as the “Richest Hill on Earth” became known for environmental travesties and mining tragedies, rather than capital expansion.

As Butte’s mining industry began to bust in the early 20th century, other areas around the state began reaping the economic benefits of resource extraction. In Libby, vermiculite mining began in 1919, when the coveted mineral was found in the mountains surrounding the quaint Montana town. By the early 1960s Libby had become the vermiculite capital of the world, when resource conglomerate “WR Grace bought the mine in 1963 it was producing 80% of the world’s vermiculite and Libby was proud of it” (Walters 2009).

Cities in Montana became inexpendable aspects of the U.S. economy throughout that time period. Libby’s vermiculite surplus supplied the globe with necessary insulation and fire repellent, while Butte’s copper was of incredible importance to the United States during the First World War. But as time moved forward and companies moved in and out of Montana, citizens were left to pick up the pieces, facing negative externalities that were often ignored in a strict market structure.

Historical Injustice to Indigenous Peoples

While mining has been heralded as the primary economic driver of many Montana communities, the relentless and reckless extraction of natural resources has left physical and emotional scars to landscapes, cultures, and communities throughout the state. History books may gloss over the incredibly problematic nature of the mining industry within Montana, but the results of over a century of resource extraction are startling and disturbing. In truth, Montana’s mining industry was built on foundational flaws, none bigger than the murder and exploitation of Indigenous peoples throughout the state.

Nearly every mining operation in the state of Montana was only made possible through the mass murder and relocation of tribes. As Montana was territorially developed, “Towns sprang up in the middle of tribal territory, often at the crossroads of important Indian trade routes. Towns and mining claims cut off Indian peoples’ access to traditional lands and water sources” (Egan, 108). Settlers deforested ideal hunting environments to develop wagon trails, overgrazed communally utilized agricultural lands, interrupted bison migration, and spread domesticated diseases to wild animals. The incredibly tragic truth is all of these atrocities pale in comparison to the explicit exploitation and genocide that prospectors brought upon Indigenous nations that opposed Anglos trespassing for the purpose of resource extraction.

In 1863, one year before the founding of Montana’s territorial capital Helena, gold was discovered in Alder Gulch within the Yellowstone River region. The Crow tribe refused gold mining along Yellowstone River. Despite initially successful resistance against settler trespassing and resource extraction, “within a few months thousands of people flooded into Alder Gulch to take part in Montana’s richest gold discovery. By the year’s end the gulch had become a string of towns 14 miles long” (Egan, 103). The Crow tribe was never compensated.

Years later, resource extraction would be the ultimate catalyst for the Great Sioux War of 1876, which was fought in the Montana, Dakota, and Wyoming territories. As prospectors in the thousands flocked to the Black Hills, completely violating the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, “which granted the Sioux nation the Black Hills, which were considered sacred grounds for the Sioux (also known as the Lakota) and Cheyenne Indians” (“Black Hills Expedition”). In Montana, the Great Sioux War holds a place in history highlighted by the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The battle was fought along the Little Bighorn River in late June 1876. The Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes came together to defeat the notorious Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Regiment of the U.S. Cavalry. This marked the beginning of a long history of unlikely alliances coming together to fight against resource extraction in the state of Montana. Unfortunately the battle was a short-lived victory for the three tribes, as more U.S. troops were brought into the field to move them into reservations. The Army forces invaded cherished Lakota Sioux hunting grounds, confined the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne people to reservations, and were able to take over the Black Hills in less than one year. Again, neither tribe was compensated (“Black Hills Expedition”).

Negative Externalities Within Mining Communities

While the Anglo settlers of Montana were not forced off their land and onto reservations, they have faced many of the negative externalities of the resource extraction industry. Throughout the state, corporate domination, employee oppression, and a plethora of health issues have plagued mining communities.

Butte

This historically tragic timeline can be traced all the way back to the days when Butte’s mining excavation turned the city into the “Richest Hill on Earth.” Initially mining in Butte represented a pristine example of a mutually beneficial workplace. Due to the three Copper Kings’ internal competition, miners were able to unionize, forming the Butte Miners’ Union of the Western Federation of Miners. Through unionization, miners were able to leverage higher wages, hour limits on shifts, and safer working environments (Punke 2006).

But after decades of copper production, Butte was gaining international notoriety as an economic gem, and outside corporations began to take notice. One such organization was William Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. In just a few short years, Standard Oil managed to purchase Marcus Daly’s Anaconda Mining Company and would go on to buy out William Clark before purchasing Heinze’s Butte holdings for twelve million dollars on the eve of World War I (Punke, 72). The dismantling of Butte’s Copper Kings’ empire did not simply represent a changing of the guard within Butte’s mining hierarchy but rather a complete and utter dissolution of unionized cooperation among miners.

New ownership and demand during World War I caused a steady decline in living conditions and complete disregard for safety measures within the mines. The 14,500 miners throughout the city worked night and day, and according to multiple sources many of the miners would sleep within the mines during their shifts. Tumultuous working conditions would inevitably result in tragedy for the miners of Butte In October 1915, just over a year into the United States involvement in World War I, there was a disastrous explosion in the Granite Mountain Mine. The explosion caused by giant powder killed 14 miners. According to the Salt Lake Tribune, many of the men were confined in an incredibly small room known as the “dog house” right outside the shaft, while no workers were “at the car of powder when it exploded” (“Fourteen Miners Killed” 1915). This brought into question the general safety of the Granite Mountain mining operation, and unfortunately would not mark the last deadly accident in the depths of the Granite Mountain mine.

On June 8, 1917, miners were moving a large electrical cable down into the mine, when the cable slipped out and fell roughly 2,500 feet underground. “The material used to insulate the cable was flammable, and when a recovery crew went to pull it out, a crewman’s open-flame lantern set the cable ablaze” (Punke, 2006). The fire would spread throughout the mine and of the 415 miners working the night shift, 163 died in the fire according to the Bureau of Mines accident report. Most of the miners died from lack of oxygen, but the accident was indirectly caused by the aforementioned increase in copper demand and a decrease in safety measures. According to Michael Punke, author of Fire and Brimstone: The North Butte Mining Disaster of 1917, “miners were given no safety training, and many had no idea how to get out of the mine if a primary escape route was blocked. Even the most basic safety precautions were absent.”

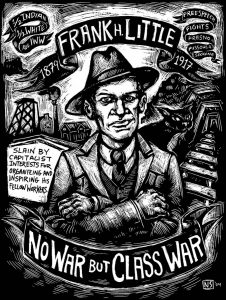

The second Granite Mountain disaster served as a catalyst for social change, as members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) flocked to Butte in support of the miners. The IWW’s intervention in Butte helped in the organization of marches, protests, and picketing of Standard Oil’s monopolization of the Butte mining industry. Over the next few decades the once prosperous town would see some sporadic copper production spikes throughout the 20th century keeping the mines afloat for some time, but income inequality led to withered public infrastructure and massive population loss. Butte would never be the same.

Libby

Moving further into the 20th century, other communities began facing comparable battles against massive resource conglomerates, including the quaint mining town of Libby. When W.R. Grace purchased the rights to Libby’s vast vermiculite supply, the town was full of optimism. As mentioned before, Libby was producing 80% of the world’s vermiculite supply, the town’s economy was bustling and productive, and the citizens of Libby were proud to be known as the world’s largest producer of vermiculite. Much like Butte’s relationship with Standard Oil, the town trusted W.R. Grace to do what was best for the local economy while making massive profits on the extraction of the cherished mineral. Little did the citizens know that Libby would become home to what the United States government has called, “the worst case of industrial poisoning of a whole community in American history” (Walters).

While vermiculite can be an invaluable resource for insulation, fireproofing, and an enhancer for the fertility of soil, some vermiculite can contain traces of asbestos fibers. When inhaled, asbestos fibers are known to cause mesothelioma, asbestosis, and in some cases severe lung cancer. In the northwestern Montana town, vermiculite mining brought many citizens an economic livelihood, but in the following decades it would also take many to the grave. Tragically, unlike the mining disasters in Butte, the negative implications of vermiculite mining did not only take the lives of miners. “Over the years, W.R. Grace & Company also had distributed leftover vermiculite for use in playgrounds, backyards, baseball fields and gardens” (Povtak).

The result of their maniacal generosity is an estimated death count of 400 and rising, while more than 2,000 citizens have faced the negative health implications of asbestos contamination (Kelley). In Libby, mining represented more than an occupation, for miners vermiculite dust was worn as “a badge of honour,” according to Gayla Mayfield, Libby’s top campaign manager in the legal fight against W.R. Grace. Mayfield elected to sue W.R. Grace after her mother’s death in 1985. Hundreds of betrayed citizens followed in Mayfield’s footsteps and as a result, “the U.S. Justice Department has indicted the company” (Walters, 2009). Libby serves as a perfect example of the importance of courage in fighting against resource extraction companies. Many citizens of Libby despised environmentalists and viewed W.R. Grace as the town’s economic savior, but as nearly 10% of the town’s population has died from asbestos contamination, the town slowly came together in fighting against the corporation.

Today, Libby is home to one of the largest Superfund sites in the U.S., after the EPA placed Libby on its National Priorities List in 2002. The Superfund designation is in large part due to the courageous acts of citizens such as Gayla Mayfield. And while asbestos contamination is still impacting citizens of Libby, “past cleanup efforts have been effective in reducing or minimizing exposure to asbestos,” according to Nick Raines, manager of the Lincoln County Asbestos Resources Program (Povtak). Needless to say, Libby’s fight with W.R. Grace has had an incredible impact on other communities, and the fight against resource extraction has never been more tenacious throughout the state of Montana.

Unlikely Alliances

Today, resource-based conflicts continue, particularly within predominately Indigenous areas, as extraction companies continue to propose projects on or near tribal lands and other areas of poverty that are vulnerable to economic blackmail. Yet resource extraction is becoming more and more complicated for corporations hoping to exploit these communities, as Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups have come together to fight against dirty and unjust resource extraction. Montanans have steadily learned from the troubling past of towns like Butte and Libby, and are standing up against corrupt resource capitalists.

For many tribes in Montana, such as the Northern Cheyenne people of southeastern Montana, this fight has been seemingly endless. As mentioned before, the Northern Cheyenne’s fight against resource extraction and forced removal can be traced back to the initial Anglo trespassing in the mid- to late-1800s. Today, the Northern Cheyenne tribe consists of around 8,000 tribal members living on about 500,000 acres, acreage that holds incredible economic potential for resource extraction companies. According to activist and Northern Cheyenne tribal member Gail Small, the battle against resource extraction has been long and tumultuous, “All my life, my people have been fighting to keep coal strip mining off our reservation. Right now, our tribal lands are surrounded by Montana’s largest coal-fired power plant and five massive strip mines—the largest coal-fired generating complex in the country. The coal companies, and the oil and gas companies, just want us out of the way” (Small, 1).

But the Northern Cheyenne refuse to move away from their cherished land and thus one of the greatest resource rebellions of the past two centuries continues to battle fossil fuel conglomerates with uncompromising vigor. In 2016, the Northern Cheyenne played an integral part in bankrupting Arch Coal, a massive St. Louis-based coal corporation. Among the reasons cited for bankruptcy were “a weak coal market, shortage of capital and an uncertain permitting outlook”—three signs that point directly towards a greener future (Brown). But the true story here is that Arch Coal would be alive and well if it were not for the Northern Cheyenne’s intense fight against a proposed Otter Creek coal mine. Otter Creek lies within the Powder River Basin an area that produces the vast majority of the nation’s coal. According to Arch Coal executives the Otter Creek mine would have produced up to 20 million tons of coal annually (Brown).

The move to fight the Otter Creek mine did not come without tangible sacrifices for the Northern Cheyenne people, as “the loss of the two projects sinks near-term hopes for a coal-fueled economic boom in southeastern Montana” (Brown). And it also did not come without strong alliances: the Northern Cheyenne tribe were able to derail the massive coal project only through ties with local white ranchers, as well as conservation groups such as the Sierra Club and the Northern Plains Resource Council. And although Indigenous communities have paid a disproportionate price for fossil fuel extraction, it seems that these type of alliances, with Indigenous leadership, may be the undoing of the industry as a whole.

Throughout Montana, alliances of Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups have been working to fight against the fossil fuel industry on a national scale. In 2015, Montana-based alliances played an integral role in derailing fossil fuel extraction across the country, through the legislative and physical blockade of interstate travel that relates to resource extraction. In Missoula, ranchers, grandmothers, university professors, and of course local tribes, united to block megaloads of equipment “sent via highways to Alberta’s tar sands where they are used to extract bitumen, a substance that can be refined into crude oil. On icy winter nights, protesters led by Native people waited by the highway for the loads to arrive” (Van Gelder). The protest was led by Native communities, but its success was in large part due to the sheer number of non-Native people that allied with the local tribes in fighting against the toxic transit.

That same year, the Northern Cheyenne were also able to stop the construction of the Tongue River Railroad, a fossil fuel-centered railroad sponsored by Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF), Forrest Mars, and of course Arch Coal. Through protests and the utilization of sovereign rights, the Northern Cheyenne were able to block a proposal that would have transferred 20 million tons of coal annually, according to the Indian Country Today Media Network. Other tribes including the Lummi (who blocked a terminal that would have received Otter Creek coal) and Quinault people have also fought against fossil fuel transportation, and it seems that fossil fuel extraction has never been more vulnerable.

The Future is Bright

While aspects of our collective future are concerning, hope is on the horizon in the Big Sky State. In 2007, Montana was home to over 2,000 “green energy jobs,” a number nearly double the jobs related to coal extraction within the state. Montana’s changing ideology undoubtedly represents hope for the future, but perhaps an even greater sign for change is that “Montana ranks fifth in the nation for wind-energy potential” and has the capacity to fill vacancies left by fossil fuel industries, with clean energy jobs for Montana citizens (LaDuke, 31). That does not mean that Montana is void of the same social and environmental concerns that plague states around our nation. Not even close: Montana has historically borne the brunt of capitalist extraction industries and the state is already facing the backlash of a Trump election. We have seen rising xenophobia throughout the state and even a neo-Nazi movement in the rural ski town of Whitefish (Beckett). We have seen our natural resources extracted recklessly resulting in massive loss of life and incredible environmental degradation. Yet, despite all that, hope is abundant in Montana because resistances continue to fight against colonial establishments and practices.

Today Montana citizens have had enough with capitalist compromise. Ideological and racial divides that once resulted in ethnocidal killings, corrupt political structures, and corporate bureaucracy are slowly dwindling as communities from very different backgrounds are fighting hand-in-hand against environmental degradation through resource extraction. The fight has just begun as racial divides continue to amplify throughout our nation. Meanwhile, Secretary of the Interior and Montana native Ryan Zinke has vocally expressed his interest in selling off private lands in order to extract fossil fuels on a national scale. Many politicians within our federal government, fully understand the vast potential Montana represents to fossil fuel companies, none more so than Zinke.

Yet hope lies in the notion that Zinke remembers the cultural and spiritual importance of Montana’s natural space as a lifelong fisherman, hunter, and outdoorsman. And if he has forgotten, I have no doubt Montanans will unite in reminding him, because there is always a way to promote change. And maybe that is the greatest place to find hope for an environmental revolution: not in statistical probabilities, not in a top-down moral revelation, but in the unprecedented environmental victories that resource rebels continue to pile up around the globe, the social movements that are painfully returning accuracy to historical narratives, and the revolutionaries who refuse to give up hope. In Montana, hope lies in unlikely alliances, cowboys and Indians, men and women, sportsmen and environmentalists, fighting together for a better tomorrow.

Sources

Beckett, L. (2017, February 5). How Richard Spencer’s home town weathered a neo-Nazi “troll storm.” The Guardian.

Black Hills Expedition of 1874. (n.d). PBS.

Brown, M. (2016, March 10). Arch Coal suspends plans for Otter Creek mine in Montana. Billings Gazette.

The City of Helena, Montana, is founded after miners discover gold. (2016, October 30). History.

Eilperin, J. (2016, December 13). Trump taps Montana Congressman Ryan Zinke as interior secretary. Washington Post.

Egan, K. (n.d.) Montana’s Gold and Silver Boom: 1862- 1893.

Fourteen Miners Killed By Giant Powder: Explosion Occurs While Powder is Waiting to Be Sent Down. (1915, October 20). Salt Lake Tribune.

Gelder Van, S. (2015, September 4). Dispatches From the Edge of Change: Why Montana’s Fossil-Fuel Resistance Gives Me Hope. Yes Magazine.

ICTMN Staff. (2015, September 23). Northern Cheyenne Council Unanimously Opposes Coal Train. Indian Country Today Media Network

Kaye, L. (2017, February 2). Plans to Sell 3.4 Million Acres of Federal Lands Spur Protests. Triple Pundit.

LaDuke, W. (2017). The Winona LaDuke Chronicles: Stories from the Front Lines in the Battle for Environmental Justice. Black Point, N.S.: Fernwood Publishing,

Michaelson, J. (2016, December 15). Will Ryan Zinke Open Up 265 Million Acres of Land to Drilling and Mining?. The Daily Beast.

Peacock, A. (2003). Libby, Montana: Asbestos and the Deadly Silence of an American Corporation. Boulder, Colo.: Johnson Books.

Povtak, T. (2016, February 19). EPA Is Close to Finishing Libby Asbestos Cleanup. Asbestos.com

Punke, M. (2007). Fire and Brimstone: The North Butte Mining Disaster of 1917. Hyperion.

Punke, M. (2006, May 31). Michael Punke: Q & A About the North Butte Disaster of 1917 …the worst hard-rock mining disaster in American history. History News Network

Small, G. (n.d.). Coal Export. Rethinking Schools

Siu, M. (2017, January 30). “Love Not Hate” event draws hundreds in Whitefish. ABC Fox Montana.

Walters, J. (2009, March 7). Welcome to Libby, Montana, the town that was poisoned. The Guardian.

Weltman, E. (2016 October, 10). Ancient Voices, Today’s Struggles: Learning from Indigenous Resistance. Food and Water Watch.