Chris Colella

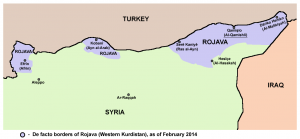

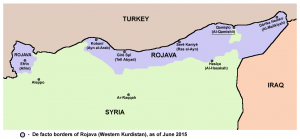

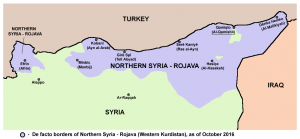

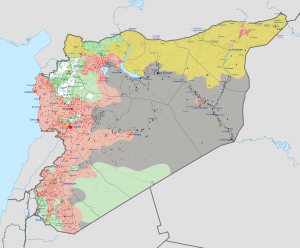

In the middle of the civil war in northern Syria is an enclave of about 4.6 million people called Rojava; since 2016, officially named the Democratic Federal System of Northern Syria. This territory, which is about the size of Massachusetts, is an autonomous region primarily of the Kurdish ethnic group, and has been exercising a sort of autonomy since the 2013 breakout of the Syrian Civil War. The region, which is divided up into three cantons (Afrin, Jazira, and Kobanî), is governed by a coalition of six political parties called the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM), which is headed by the Democratic Union Party (PYD). They practice a governance model called “Democratic Confederalism”: a kind of libertarian socialism founded on the ideas of Abdullah Öcalan and Murray Bookchin. Though Rojava is primarily Kurdish and Muslim, it also includes many Arabs, Assyrians, Yazidis, and Christians as well, as reflected in the Social Contract’s dedication to diversity and pluralism.

The PYD is an affiliate of the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK), which has been active in Turkey since 1978, led by Abdullah Öcalan. The PYD has a military wing called the People’s Protection Units (YPG), as well as the all-female Women’s Protection Units (YPJ). There is also a security force in Rojava called the Asayish, which are elected and go through a two- week “feminist instruction” before being given weapons; in addition, a women-only force deals with issues of rape and sexual assault (Enzinna). The focus on women’s liberation in Rojava comes from the left-libertarian ideology of Abdullah Öcalan, which includes a brand of feminism called “Jineology” (“women’s science”) as one of its main focuses, alongside participatory democracy, social economics, and ecological sustainability.

If Rojava should continue its success, it will be the second partial homeland for the stateless Kurdish people, the first being the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in northern Iraq, where U.S. military action backed a no-fly-zone for Saddam Hussein’s air force after the 1991 Gulf War. The KRG is modeled on Western “democracies,” whereas Rojava is an anarchist-influenced libertarian system. Rojava also has been butting heads with the Syrian government, the Syrian opposition, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS or Daesh), the Turkish government, and the KRG in various capacities over the course of its existence.

Rojava is an interesting phenomenon in the Middle East right now, and almost the complete antithesis to what Daesh hopes to be. It is anti-nationalist (though often called a Kurdish nationalist movement), and supports gender equality, religious freedom and separation of church and government, participatory democracy, and the protection of the rights of all ethnic, religious, and language groups. Anarchist activist and anthropologist David Graeber, a major figure in the Occupy movement, said ‘‘the autonomous region of Rojava, as it exists today, is one of few bright spots — albeit a very bright one — to emerge from the tragedy of the Syrian revolution’’ (Graeber).

History of Kurdistan

The history of the fight for a Kurdish homeland began in 1916, when Britain and France divided up the Middle East with the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which left the Kurdish people divided between Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran (Enzinna). The Turkish government made laws declaring everybody in Turkey to be an ethnic Turk, forcing those who were not to either give up their ethnic identity or to legally not exist. Turkish laws also erased Kurds from history books and banned speaking Kurdish in public. Laws even existed banning the letters Q, W, and X, which were in the Kurdish alphabet but not the Turkish alphabet. Similar laws existed in Syria and other countries as well.

In 1962, the Syrian government took a census of predominantly the Kurdish region, and declared that tens of thousands of them had migrated there illegally, and stripped them of citizenship (Zaman). This left about 150,000 Kurds stateless, which denied them the right to own property, businesses, or cars, as well as preventing them from running for public office or leaving the country.

In 1978, Abdullah Öcalan (often called “Apo,” the Kurdish word for “uncle”), along with two dozen others, formed the PKK, a Marxist-Leninist party which waged an insurgency against the Turkish state with the hopes of establishing a socialist state of Kurdistan. As the organization and the insurgency grew, Öcalan spent most of this time in exile in Syria, essentially acting as leverage for Hafez al-Assad over the Turkish government. The PKK were declared a terrorist group by the United States government in 1997. And in 1998, Öcalan was captured a sentenced to death (later to be commuted to life imprisonment due to the abolition of the death penalty) (Harp). While serving as the sole prisoner on Imrali island, Öcalan took to reading the works of Western thinkers such as Michel Foucault and Benedict Anderson. At some point, he was given a copy of a book by Murray Bookchin, and quickly requested everything Bookchin had ever written (Enzinna).

Through studying Bookchin (and briefly communicating with him through lawyers before Bookchin’s death in 2006), Öcalan left behind his previous authoritarian Marxist-Leninist ideology in favor of a more libertarian, anarchistic ideology based around feminism, decentralization, and ecology, which Öcalan dubbed “democratic confederalism.”.In 2011, Öcalan issued a pamphlet entitled “Democratic Confederalism,” which contained a description of his ideas for a sort of stateless democracy, including communal assemblies and direct democracy, as well as placing an emphasis on the equality of women. And a year after the Syrian uprising began, in 2012, Bashar al-Assad (who had succeeded his father as Syrian president) pulled his forces out of northern Syria, which gave allies of the PKK and followers of Öcalan the perfect opportunity to put their ideas into practice.

The Ideology of Democratic Confederalism

The three pillars of Abdullah Öcalan’s democratic confederalism are a democratic and autonomous society, gender equality, and ecological sustainability. While in solitary confinement, Öcalan was greatly influenced by Bookchin’s The Ecology of Freedom, in which Bookchin argueed that hierarchy is root of all social problems, and that social problems are the root of ecological problems. Bookchin’s idea to follow the “Hellenic model” of face-to-face democracy in municipal assemblies presented to Öcalan a new idea. Rather than taking state power, the PKK could establish democratic communities within existing states and live regardless of the state. In March 2005, Öcalan issued a “Declaration of Democratic Confederalism in Kurdistan,” which insisted that PKK fighters stop focusing on fighting the Turkish government, and instead focus on establishing municipal assemblies. He also recommended that all PKK fighters read Bookchin’s The Ecology of Freedom. Through establishing democracy without a state, the assemblies would confederate across national borders into Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey in order to create a free society intent on sustainability, pluralism, self-defense, and women’s liberation (Enzinna). A letter to Janet Biehl, Bookchin’s late-life partner, from the PKK said “Bookchin has not died… We undertake to make [him] live in our struggle.”

The Social Economy

The economic model of Rojava, often dubbed the “social economy,” is based on networks of assemblies and cooperatives established to meet the needs of the communities. The goal of the cooperatives is to provide for people’s needs affordably and autonomously. Due to the embargo by Turkey, self-sufficiency has been a priority for the people of Rojava. The embargo, combined with Daesh control of major dams along the Euphrates River, has caused Rojava to be deficient in basic necessities such as water and electricity (Özkahraman). However, despite (or perhaps because of) the lack of resources, food and meals are eaten communally and shared with guests and neighbors far more often than not, with guests given second portions whether they ask for it or not (Harp).

The cooperative economy is part of the larger goal of the Rojava Revolution to democratize all of society, including but not limited to the economy. This also means that traditionally marginalized groups (such as women) getting a say in decisions becomes a priority, to ensure the democratic nature of the model. This model of economic democracy allows for lived experience, collective will, individual needs and desires to control the production and distribution of goods, as opposed to the impersonal inequalities of a free-market economy or the paternalistic from-above control of state intervention. Democratic economics also allows for local job creation, locally sourced products, and job training for previously unskilled workers.

As with other Kurdish-majority areas in the Middle East, Rojava had been deliberately underdeveloped by the Syrian government. Infrastructure, education, health care, industry, and factories were all built in primarily Arab regions, which has made Kurds dependent on those areas for survival. But the cooperative economy and localized, miniaturized production is allowing the Kurds to achieve economic independence and meet the people’s needs (Azeez). Cooperatives range in purpose from agriculture to textiles, from dairy production to sewing. Many women’s cooperatives have started specifically to provide jobs for and meet the needs of women. Democratic control over the economy also provides a much more equitable distribution of wealth. Journalist Seth Harp said of his time visiting Rojava, “I saw no rich people, no corporations, no banks, no big houses, no fancy cars, no one homeless or begging or starving. The people were of one class and improbably cheerful” (Harp).

Some people living in Rojava are skeptical of their ability to develop enough economically to sustain the project. “Sure, in the past five years we witnessed developments that we could never have imagined,” said a teacher in Rojava, “I can finally speak my own language freely and the Kurds are defending themselves for the first time, but otherwise nothing seems to work, and our standard of living has dropped” (Zaman). Others are more optimistic, as a jeweler from Derik said “There is stability and security here, and business is better since Assad withdrew… In times like these I can display all my gold in this window — imagine” (Zaman). The biggest problems of resource scarcity have been caused by the blockade by Turkey, which limits funding, travel, and trade from coming in and going out of Rojava.

Women’s Liberation

Women’s cooperatives, and other activities such as self-defense, justice, social issues, art, and much more, are often supervised by the women’s group Kongreya Star (“Star Congress”), which formed in 2005 as Yekîtiya Star (“Star Union of Women”). Due to Kongreya Star’s formation before the beginning of the revolution, the women involved already had some degree of experience in self-organization and have been fairly successful at organizing cooperatives and communes since the regime withdrew from the region. Midya Qamishlo, representative for the Qamishlo Women’s Economic Board, said that the women’s cooperatives “allow women to gain confidence and to support their family during the current economic crises. However, of more importance is the role that cooperatives play in collective efforts at achieving a free life and more specifically free women. They help to challenge the patriarchal structure of society by ensuring a level of equality is established. When women retake their traditional role of being major contributors within the economy men are challenged to view and revise their perception of women’s role within society” (Azeez). Cooperatives have been established planting and growing fruit trees, a practice which had been banned under the Assad regime.

Kongreya Star hopes that its efforts in Rojava and Syria will become an example for women’s liberation throughout the entire Middle East. It hopes to not merely include women in the existing society, but to question and reshape the society altogether. Kongreya Star’s strategy for achieving this goal utilizes five umbrellas: “the organization of the communes; establishing a communal economic system; providing education; the organization of self-defense; and the development of women’s science—also referred to as ‘Jineology’” (Clarke-Billings). Kongreya Star has already set up nine central committees of education in nine different towns, in which representatives receive classes on literacy in the Kurdish language, history, democratic confederalism, and women’s rights, with the expectation that they will then teach the women of their communes.

Another important aspect of women’s liberation in Rojava has been the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), which formed in 2012 as an all-women brigade of the People’s Protection Units (YPG). YPJ fighters will often make a high-pitched yelling sound when they shoot Daesh fighters in order to make them aware that they are being attacked by women, as it is the belief of Daesh that they will not get into paradise if they are killed by a woman. A young Yazidi man whose village was liberated from Daesh by the YPJ said that “the battle made me think of women differently. Women fighters — they saved us. My society, Yazidi society, is more, let’s say, traditional. I’d never thought of women as leaders, as heroes, before” (Enzinna). Any command position in the YPG/YPJ is jointly shared by a woman and a man, a characteristic shared with all other government positions in Rojava. A report from Kongreya Star reads: “self-defense is a natural characteristic of all life. A flower protects itself with thorns; a chameleon changes color according its environment; a turtle can retract inside its shell. Societies have always adapted and changed in order to defend themselves against attacks. However, with the emergence of the nation-state, self-defense has become part of the monopoly of the state” (Azeez). It goes on to say that “our goal is to overcome all forms of domination, power, ownership and sexism to establish a truly free society.” Within the YPG/YPJ there are no ranks, leaders are elected democratically, and people are addressed by the universal gender-neutral term “hevalê”, meaning “friend.”

Fighting Daesh

The YPG gained international attention in 2014 when it successfully defended the city of Kobanî from Daesh, one of the last strongholds along the Turkish border against Daesh at the time. Since then, the SDF have had a quite successful campaign liberating towns in northern Syria from Daesh rule, and establishing communes. A group of international volunteers in the YPG, called the International Freedom Battalion, has also garnered much media attention (recalling the international brigades during the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s).

One of the keys to Rojava being able to provide for itself is to have access to the hydroelectric dams that once supplied the region with power. In order to do this they need to expel Daesh from the Euphrates River and take control of the towns and dams along the river. One of the largest cities in the region, Raqqa, which serves as the headquarters of Daesh, is exactly the city it needs to take in order to get control over electricity supplies. And on November 6th, 2016, the YPG/YPJ launched a major offensive on Raqqa to liberate the city. The first phase was taking the satellite village of Tal Saman, about 17 miles north of Raqqa. Refugees pour out of the city as the fighting continues, hiding where they know they will be safe, behind the Kurdish line.

Another goal of the YPG/YPJ is joining the cantons that make up Rojava, as there is a large gap between two of them, a difficult position to be in in the middle of a war. The U.S. government encouraged Rojava to take care of that once Daesh has been driven out of Raqqa. The U.S. has been aiding the YPG/YPJ in their fight against Daesh, which has been controversial among leftists around the world. However, the town of Jarabulus, a strategic point for establishing a link between the cantons, was recently seized from Daesh by the Turkish government, which has put a halt on connecting the cantons for now. There have been rumors of collaboration between the Turkish government and Daesh in order the prevent the success of Rojava.

Recent Developments & The Future

As of now, despite its commitment to ecological sustainability, Rojava produces 15,000 barrels of oil a day (Enzinna), as its main export to the Assad regime as well as for use in its own fight against Daesh and for providing electrical power to the people of Rojava. But what will allow Rojava to maintain ecological sustainability and provide for its people will be the Euphrates. Once it has control of dams and reservoirs, it will be able to supply energy without fossil fuels. This will also give the Kurds a supply of drinking and agriculture water, as currently water is twice as expensive as oil in Rojava due to a lack of supply (Özkahraman).

Issues of water have been central to the Syrian Civil War, and have been a main source of conflict. It has been said that water would be a source of conflict between nations, but in the Syrian conflict it has been a struggle within the nation, with the added threat of Daesh controlling major dams and reservoirs along the Euphrates. Additionally, Turkey has made it clear that it does not want Rojava to extend to the west bank of the Euphrates, and that if the Kurds do not retreat to the east side of the river there will be consequences. But it is already clear that if there is no water, then there can be no Rojava, so it must push forward against Turkey to get access to the river, and to connect the space between the Afrin and Kobanî cantons if it wishes to survive.

The fight against Turkey, Daesh, al-Nusra (al-Qaeda affiliate), the Western-backed Syrian Opposition, the occasional clashes with the Assad regime and the Kurdistan Regional Government, and opposition to any other threats to liberation are going to have to continue if they are going to further the project of greater human freedom. Rojava is a beautiful, though clearly not perfect, example of libertarian socialist ideas put into practice. Rojava questions capitalism and the state, and provides a liberating alternative to imperialism, nationalism, and Islamism for the people of the Middle East. YPJ commander Deniz Derik said “everyone has to choose a side now, ISIS has chosen the side of slavery. We’ve chosen the side of freedom” (Enzinna, 2015). And so the fight for freedom pushes on.

Sources

Azeez, H. (2017, Jan. 26). Women’s Cooperatives: a Glimpse into Rojava’s Economic System. Kurdish Question.

Black Rose Burlington. (2016, March 14). Report-back from the Revolution in Rojava: Janet Biehl [Video file].

Clark-Billings, L. (2016, Oct. 6). The Women Leading a Social Revolution in Syria’s Rojava. Newsweek.

Enzinna, W. (2015, Nov. 24). A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS’ Backyard. The New York Times.

Glioti, A. (2016, Sept. 9). Rojava: a Libertarian Myth Under Scrutiny. Al Jazeera.

Graeber, D. (2014, April 4). Why is the World Ignoring the Revolutionary Kurds in Syria? The Guardian.

Gupta, R. (2016, March 30). Rojava: a Safe Haven in the Middle of Syria’s Brutal War. CNN.

Harp, S. (2017, Feb. 14). The Anarchists vs. the Islamic State. Rolling Stone.

Heller, S. (2016, Nov. 29). Keeping the Lights On in Rebel Idlib. The Century Foundation.

Jong, A. (2016, Nov. 30). The Rojava Project. Jacobin.

Loo, P. (2016, Dec. 13). The Kurdish Revolution — a Report from Rojava. Red Pepper.

Özkahraman, C. (2016, Dec. 21). Rojava, where Water is Twice as Expensive as Oil. OpenDemocracy.

Perry, T. (2016, Dec. 28). Syrian Kurds, Allies Set to Approve New Government Blueprint. Reuters.

Roza Film. (2017, Jan. 25). Documentary Of Rojava Revolution “ROZA – THE COUNTRY OF TWO RIVERS [Video file].

Taştekin, F. (2017, Jan. 25). Syrian Kurds Rebuilding Kobani from Rubble. Al Monitor.

Vice. (2014, Jan. 2). Rojava: Syria’s Unknown War [Video file].

Zaman, A. (2017, Jan. 27). Hope and Fear for Syria’s Kurds. Al Monitor.