Mo Dole

For most, when thinking of a commodity, it is not likely that one’s own body would come to mind. However, bodies are commodified every day, most visibly through slavery, sex work, pornography, the beauty industry, and more. This study will focus specifically on the commodification of transgender and gender non-conforming bodies. Trans bodies are commodified in many ways similar to those listed above and experienced by cisgender (non-trans) folks, but with different nuances.

Trans bodies are commodities in that they want, need and/or are increasingly pushed by both capitalism and the public to spend money on expensive ways of transitioning to better fit their own gender. For trans folks who choose to have surgery, take hormones, or undergo other transition-related procedures, the body is rebuilt at an exorbitant price.

Trans bodies are commodities in many other ways as well. A disproportionate number of trans people, especially trans women of color, participate in sex work, and in both sex work and in porn, trans people are considered a niche or “exotic” category (Fitzgerald). Trans bodies are also commodified in the media, whether it is an interview of a person’s transition complete with invasive questions about their genitalia or sex life, or a sensationalist article about another murdered trans woman of color. Trans bodies, including dead trans bodies, are exciting to the media because they push boundaries thought to be impenetrable, because they make people uncomfortable. These points are important because they highlight the background against which this article exists. More specifically, however, this study will deal with the commodification of trans bodies through very expensive transition-related procedures, including surgery, hormones, and more.

This study acknowledges the existence of people who are intersex, non-binary, or of an identity not pertaining to Western ideas of gender as they currently stand (including Two-Spirit, hijra, and other identities), or any combination thereof, as these people may or may not identify as being trans. The article also acknowledges that not all trans people or gender-nonconforming people wish to have surgery or take hormones, and that not all people who wish to have or have had these procedures identify as trans).

Rebuilding the Body: What are the Costs?

Financial Costs

Transitioning physically is extremely expensive. The price estimates from the Philadelphia Center for Transgender Surgery are the most comprehensive list. These prices are meant to give an estimate towards the cost of transitioning in the U.S. Costs abroad differ, as will be discussed later.

The major surgery many trans women (and others) seek out is bottom surgery, also known as gender/sex reassignment surgery, or gender confirmation surgery (this study will use the latter). The procedure is a generally vaginoplasty, in which surgeons construct a vagina using a variety of techniques. This procedure, including the cost of a hospital stay and anesthesia, which the Philadelphia Center factors in, costs about $20,000 (A more complete breakdown of the costs involved for both trans women and men can be found at the Philadelphia Center’s webpage, sourced below). Other surgeries include breast augmentation, $8,000; orchiectomy (removal of testicles), $5,000; and various facial feminization surgeries. In total, the price for a trans woman’s surgical transition can run up to (and beyond) about $140,000 (MtF Price List).

And yet that is still not the full picture. The prices listed on the Philadelphia Center do not include the cost of a lifetime supply of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT), travel costs, time off work, electrolysis (an expensive hair-removal procedure that many clinics require patients to have prior to undergoing a vaginoplasty), and other expenses. HRT alone can cost about $1,500 per year, and both the treatment and expenses continue throughout the rest of a person’s life, or until they decide to or are forced to go off them (Bell).

For trans men (or others seeking the same surgeries but who do not identify as men or as trans), bottom surgery or gender confirmation surgery can cost up to $20,000 as well, depending on the procedure performed and additions like testicular implants or the construction of a scrotum. Top surgery, or the removal of breasts and/or “masculinization of the chest” costs about $5,000 to $8,000 depending on the procedure. Facial surgeries are also an option for transmasculine people. Overall, the price for a trans man’s surgical transition can run up to and beyond $120,000, but once again this estimate does not factor in the cost of HRT and other expenses (FtM Price List).

Additionally, it is important to note that the Philadelphia Center’s prices are midrange–costs for these surgeries in the U.S. can run much higher, especially for transmasculine people, as gender confirmation procedures for these individuals are often more complex and therefore more expensive (Bell).

(Lack of) Insurance Coverage

Most surgeries in the U.S. are very expensive–health care in this country tends to be. However, the difference between those expensive surgeries and the expensive surgeries specific to trans people is that of coverage. Many insurers refuse to cover transition-related costs, calling these surgeries and procedures “cosmetic” and “not medically necessary” (Frisch).

However, these services are by no means merely cosmetic, they are lifesaving procedures. For trans people for whom physical transition is important, surgeries and HRT are instrumental in making them feel more at home in their body and feel safer in public (the notion of “passing” is a complex one, but it is indisputable that passing as cisgender significantly reduces the risk of violence and harassment one receives on a daily basis). Trans people also seek these surgeries so that they can update legal documents to better match their gender identity and presentation, because many states require trans people to provide proof of having had gender confirmation surgery before they can legally change their gender marker on official documentation. This can be a source of both dysphoria and violence, as an incongruity between someone’s perceived gender and the marker on their I.D. often causes people in positions of power to react with hostility or violence (Lambda Legal).

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as Obamacare, includes provisions that prohibit insurance companies, hospitals, and health programs that receive federal funding from discriminating against transgender individuals. However, as stated above, this only applies to institutions that receive federal funding: Medicare does follow this policy and even provides limited coverage of transition-related services. Private insurers and Medicaid (which is funded by the state, not federally) are merely “encouraged” to adopt these anti-discriminatory policies (DeMichel). Below is a May 2016 map of the U.S. showing the few states which have voluntarily constructed explicit bans on transgender discrimination in health care in dark blue, in accordance with the ACA (the four light blue states have adopted some protections).

It is important to note that the ACA also does not require insurance companies to cover transition-related services like surgery. Even insurers who voluntarily or involuntarily adopt anti-discrimination laws for basic medical services to trans people are under no obligation to cover costs for physical transition (DeMichel).

Even When Insurance Covers it…

Even when insurers do cover transition-related services, they often do not cover all necessary surgeries. For instance, while chest reconstruction for transmasculine people is covered under most insurance plans that cover transition services, the corresponding procedure for transfeminine people, breast augmentation surgery, is often deemed cosmetic, and therefore not covered (Frisch). (‘Transmasculine’ is a term used here to describe trans people who lean towards the masculine in their gender identity or expression, but who may or may not identify as trans men. ‘Transfeminine’ is its counterpart for those who lean toward the feminine).

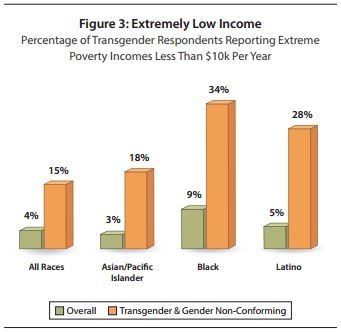

Yet even when insurers cover the necessary surgeries, they still do not always cover the whole cost. Oftentimes this results in policies that look good on the outside but are of very little use to the trans people it purports to support. This is particularly harmful because trans people are more likely to have very low incomes, compared to both the general population and other LGB people. The likelihood of poverty increases even further for trans people of color, as shown in the graph below.

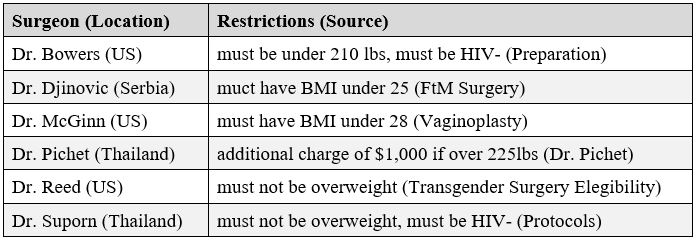

Furthermore, even if an individual’s insurance company covers a procedure, problems still persist among available surgeons. Many surgeons in the U.S. and abroad have weight limits instituted, as well as other restrictions such as HIV status. Basic research gathered by the author both from online sources like the webpages of the below listed surgeons, and from conversations with other trans people, shows that these requirements vary widely from surgeon to surgeon. These requirements exclude many trans people from essential surgeries on the basis that they are “harder to perform” (FAQ: BMI Requirements).

This discussion is of course nuanced, but the fact remains that it is part of a larger pattern of fatphobia and discrimination against people who are HIV+ in the medical community. It was included here briefly as an example of one of the many discriminatory policies that trans people may face even if they do get coverage for surgery. Yet another problem is that an insurance company may cover the procedure, but there might not be any surgeons in the area willing or able to perform the surgery. In this scenario, the individual would need to pay out-of-pocket to travel to where there is an available surgeon covered by their insurance, something not everyone can afford to do.

These barriers are mighty, frightening, and ripe for disruption, but there is still hope for the future. In the face of these obstacles, many determined trans people and allies are doing the essential work of dismantling, working around, and even using these very structures in order to get themselves and others much-needed medical care for their physical transition and beyond.

Resistance and Resilience

When trans people cannot pay for surgery or hormones out-of-pocket, their insurance company will not cover the cost, or they are uninsured, there are a variety of ways they can attempt to get the necessary procedures, with varying degrees of success and accessibility. These include—but are not limited to—partnering with clinics or law centers to fight to get insurance coverage of the procedure, traveling abroad to get the surgery for cheaper, finding alternate ways to access the procedures like purchasing and using hormones on the black market without a doctor’s supervision, or using crowdfunding or grants to cover the medical costs.

Partnering with Clinics

One organization that trans people can go to for help is the Transgender Health Program (THP) at St. John’s Well Child and Family Center in Los Angeles, California. The THP was formed in January 2013 as a response to “the lack of transgender health care on the national and local level, and particularly in St. John’s service area of South Los Angeles” (Sussman, 5). It provides transition-related services (hormones, referrals for surgery), legal support, primary and preventative care, mental health care, HIV and STI testing and treatment, assistance with enrolling in health insurance, assistance with changing legal names and gender markers, and more (Sussman, 25).

The clinic is staffed by medical providers trained in how to interact with and provide care to transgender people, and the THP itself is advised by a Transgender Advisory Board staffed entirely by transgender people from the community, some of whom are current or former patients (Sussman, 27). The clinic sees every individual regardless of their ability to pay, and turns no one away for lack of eligibility for insurance (an issue that is particularly critical for undocumented people) (Sussman, 26). The THP also recognizes and cares for not just binary trans people (trans women and trans men) but also other gender nonconforming people like those who are nonbinary, two-spirit, genderfluid, and more (Sussman, 4).

The Rainbow Health Center is a small clinic in Olympia, Washington that opened in May 2016 and is trying to provide similar services. As of now, it has only mental health providers enrolled in the program, but it is currently seeking providers of physical health with experience in providing HRT, transgender medical care, and after surgery care; providers with experience in electrolysis and esthetics; and masseuses. The center currently offers an ADA-accessible Community Room (that is, a room that meets the Americans with Disabilities Act Standards for Accessible Design) available for rent after regular business hours, which provides space for meetings, events, and small classes (Rainbow Health Center).

Partnering with Law Projects

Transgender people seeking legal help can also go to law centers such as the Sylvia Rivera Law Project or the Transgender Law Center (TLC). According to its mission statement, the TLC “changes law, policy, and attitudes so that all people can live safely, authentically, and free from discrimination regardless of their gender identity or expression” (Mission, Vision, and Values). The TLC changes policy and attitudes around transgender people through legal means and through spreading information in a variety of areas, including workplace discrimination, family law (marriage, adoption, etc), health, housing, identity documents, incarceration, immigration, public accommodations (such as bathrooms), youth services, and much more (Our Legal and Policy Work). The center also represents individual transgender people in legal battles, such as in the case of Shiloh Heavenly Quine.

Shiloh Heavenly Quine is a transgender woman who, until January 2017, was being housed in a men’s prison in California. In 2014, Quine filed a complaint requesting that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) provide her with gender confirmation surgery as a medically necessary treatment to her gender dysphoria, as well as access to commissary items the CDCR made available to cisgender women in their facilities. Quine was represented by the TLC and received pro counsel from Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP.

On August 7, 2016, the CDCR conceded that the surgery was medically necessary, and agreed to move Quine to a women’s facility after she received the surgery, where she would have access to women’s commissary items. Additionally, as part of the settlement, the CDCR revised its policies so that transgender inmates can access commissary items consistent with their gender identity, and created a policy to allow transgender inmates access to medically necessary surgery (California Correctional Health Services, Transgender Law Center). In January 2017, Quine received the surgery and was moved to a women’s facility shortly afterwards (Associated Press).

Traveling Abroad

Another way some transgender individuals are able to access surgery is through traveling to where costs are much cheaper than here in the U.S. However, there is always a balance to be struck. Often, the lower costs of the surgeries is outweighed by the added costs of traveling to and staying in these foreign countries, and potentially by the different standards of care offered there.

One of the most common places outside the U.S. for gender confirmation surgery right now is Thailand, in part because of the reputation built up around one particular surgeon in Bangkok, Dr. Preecha Tiewtranon, and in part because of lower prices. There, gender confirmation surgery costs about a third as much as it does is the US, and yet the quality generally remains the same or better.

Dr. Preecha Tiewtranon is likely the most renowned surgeon in Thailand (and perhaps even South-East Asia) performing gender confirmation surgeries, and is a pioneer in the field who has trained many of the other surgeons performing these operations in Bangkok today. He heads the Preecha Aesthetic Institute, and with the help of his five-person surgical team, has performed over 3,500 gender confirmation surgeries over the past 30 years, with price packages (including surgery, hotel accommodation in the city, and even a massage) starting at about $10,000. Most of their clients come from outside Thailand–in particular China, the Middle East, and Australia (Gale).

Another surgeon who performs these procedures in Bangkok is Thep Vechavisit, who provides perhaps the cheapest gender confirmation surgeries in Thailand. A vaginoplasty here costs about $2,000. Vechavisit keeps costs down by using only local anesthesia and sedatives instead of general anesthesia, no anesthesiologist, and no hospital operating theater. In place of a dilator (a device vaginoplasty patients must use regularly to prevent their new vaginas from shrinking) that many Thai clinics charge hundreds of dollars for, Vechavisit offers his patients something he can provide for free: a stick. He operates in a small clinic in a low-rent district, and performs these time-consuming surgeries even when they mean he makes less money. He says, “You have to understand, some people need the surgery. You cannot say no” (Gale).

For more information about gender confirmation surgery outside the U.S., as well as analysis of the media’s portrayal of these so-called “sex change capitals,” see Bucar and Enke’s Unlikely Sex Change Capitals of the World.

Going Outside the Law

For some trans people, especially youth, getting access to HRT is just as big a hurdle as surgery. One’s doctor could refuse to sign a prescription for the hormones, the pharmacy could refuse to fill it, or one’s insurance company could refuse to cover it. One could also be uninsured, and additionally many trans youth are living with unsupportive parents who can prevent their child from gaining access to HRT through legal means.

In response, some trans people purchase hormones illegally online, or buy them through a friend. These hormones are unregulated, with no guarantees of quality or accurate dosage. If used incorrectly, the doses can be lethal, or they can be mixed with some other compound. Despite the risk, many trans people continue to purchase hormones this way because they have few other options. In response, many clinics such as the Transgender Health Program at St. John’s described above are trying to make legal, doctor-regulated access to HRT easier and more affordable so that transgender youth and adults can transition without putting their health so much at risk (Dewey).

Other Ways to Pay

Other ways transgender people get surgery and HRT if insurance won’t cover it or they cannot afford it out of pocket is by finding other ways to pay for it, like crowdfunding or seeking the assistance of beneficiary organizations.

Crowdfunding

Recently, many trans people, especially youth, have been successful in raising money online to fund their surgeries. Trans people campaign on sites such as Kickstarter, Indegogo, and YouCaring to gain the financial support of strangers, using the media attention trans people get (good and bad) to their advantage. These campaigns vary depending on the individual creating them and the site on which they are hosted. For instance, Kickstarter focuses on the creation of a product, and requires campaigners to provide scaled rewards for different levels of donations. This requirement for a final product can be bent to fit the needs of trans people seeking surgery, however, as in the case of Ashley Altadonna, who in 2012 successfully raised $6,000 to a make a film documenting her own attempts to fundraise the $20,000 she needed for surgery (Farnel 219, 220).

Indiegogo, meanwhile, does not require a final product, and offers merely a suggestion that campaigners provide perks for their backers, and YouCaring is a site that focuses entirely on providing funding for medical expenses, memorials, and funeral. The many different sites for online fundraising change how campaigns are structured and presented to the public, with varying levels of success. However, crowdfunding is not for everyone. Many people do not have regular access to computers or the internet, and not everyone has the story or the skills to weave a narrative that compels strangers to donate to their cause. As Dru Levasseur, co-founder of the Jim Collins Foundation (discussed below) puts it, “you shouldn’t have to be charismatic to get health care” (Bahler).

Grants

Another way trans and gender-nonconforming people can get funding for surgery and hormones is through appealing to charitable organizations, like the Jim Collins Foundation (JCF). The JCF is a non-profit organization that offers grants to applicants each year to fund gender-confirming surgeries. How many grants are offered depends on the amount of money garnered from fundraising and donations the JCF receives, but since the program’s inception in 2011, between one and three people have received a grant each year (About Jim Collins Foundation).

My Transition Funding is a similar non-profit organization started in 2015 that also awards grants for surgery to transgender applicants (My Transition Funding). Other grant-awarding organizations include the Community Kinship Life Scholarship Fund (Surgery Scholarship), and the Point of Pride Annual Transgender Surgery Fund (Annual Transgender Surgery Fund).

Conclusion

All of the examples above are methods trans people use to gain access to services that are denied to them initially, whether by medical professionals or by exorbitant costs. They are examples of dedicated individuals and organizations working together to fight anti-trans legislation and biases. However, this is by no means a sign to stop fighting, that other people have it covered. In contrast, the public must fight now harder than ever to protect and meet the needs of trans adults and youth, and this starts first and foremost by listening to us.

A Note on the Sources Used

Of the many articles and essays I read to write this webpage, there existed a fairly distinct two-way split. When it comes to transgender news and discussion in the media, there is not much room for middle ground. Many of the articles I read were sensationalist at best, and demeaning and discriminatory at worst. For instance, nearly every article I found discussing transgender inmate Shiloh Heavenly Quine remained hyperfocused on the crime she committed in 1980 that landed her in jail, and nearly all were titled with variations on “California Killer Is First U.S. Inmate To Have State-Funded Gender Confirmation Surgery” (Papenfuss). That example is a headline from The Huffington Post, a news site considered to be fairly liberal.

The other strain of articles I found tended to be from explicitly trans-friendly organizations, such as the Transgender Law Center, or from trans people themselves. I tended to focus on these sources, as they were generally the least sensationalist, least rude, and most accurate. There did of course exist some articles which inhabited the middle ground, and I drew on some of these for my research as well, namely Bloomberg’s articles on gender confirmation surgery in Thailand, and California Correctional Health Services’s release statement on policy changes relating to gender confirmation surgery (Gale, California Correctional).

Sources

About Jim Collins Foundation. Jim Collins Foundation.

Annual Transgender Surgery Fund. Point 5cc.

Associated Press. (2017, February 1). Inmate who got Sex Reassignment Heads to Female Prison. The Detroit News.

Bahler, K. (2014, December 1). A Growing Number of Trans Americans are ‘Crowdfunding their Gender Transitions. The Huffington Post.

Bell, G. (2016, November 21). How Much Does Gender Reassignment Surgery Actually Cost?. Heat Street.

Bucar, E. & Enke, A. (2011). Unlikely Sex Change Capitals of the World: Trinidad, United States, and Tehran, Iran, as Twin Yardsticks of Homonormative Liberalism. Feminist Studies, 37 (2), 301-328.

California Correctional Health Services. Guidelines for Review of Requests for Sex Reassignment Surgery. (2016, May 24). California Correctional Health Services.

Center for American Progress, & Movement Advancement Project. (2015, February). Paying an Unfair Price. LGBT Map.

Dewey, C. (2016, January 29). How the Internet Black Market Profits off Trans Discrimination. The Washington Post.

DeMichel, T. (2016, May 24). Final Rule Prohibits Discrimination in Health Care. ObamaCare Facts.

Doezma, Marie. (2013, October 2). Global Medical Tourism and Sex Reassignment Surgery. The Investigative Fund.

Dr. Pichet Sex Reassignment Surgery Guide, Includes Cost. TS Surgery Guide.

FAQ: BMI Requirements for Phalloplasty. Belgrade Center for Genital Reconstructive Surgery.

Farnel, M. (2015). Kickstarting Trans*: The Crowdfunding of Gender/Sexual Reassignment Surgeries. New Media and Society.

Fitzgerald, E., et al. (2015, December). Meaningful Work: Transgender Experiences in the Sex Trade. Trans Equality.

Frisch, I. (2015, August 9). California Healthcare Appeal Sets Precedent for Transgender Coverage. Broadly.

FtM Price List. The Philadelphia Center for Transgender Surgery.

FtM Surgery: Healthy Weight Management Before FtM Phalloplasty. Sava Perovic Foundation.

Gale, J. (2015, October 26). How Thailand Became a Global Gender-Change Destination. Bloomberg.

Gale, J. (2015, October 26). Transgender Tourism: For $2,000 a New Life Begins. Bloomberg.

Lambda Legal. (2017). FAQ About Identity Documents. Lambda Legal.

Lyseggen, K. (Photographer). (2014, December). Shiloh Heavenly Quine.

Mission, Vision, and Values. Transgender Law Center.

MtF Price List. The Philadelphia Center for Transgender Surgery.

My Transition Funding. My Transition Funding.

National Center for Transgender Equality. (2016, May 13). State Health Insurance Rules. National Center for Transgender Equality.

Our Legal and Policy Work. Transgender Law Center.

Papenfuss, M. (2017, January 8). California Killer Is First U.S. Inmate To Have State-Funded Gender Confirmation Surgery. The Huffington Post.

Pickett, Hazel. (2016, October 13). How My Miscarriage Bridged the Gap Between Gender Identities. The Huffington Post.

Preparation (GRS). Marci Bowers, M.D. MtF Transgender Surgery.

Protocols. Suporn Clinic.

Rainbow Health Center. Rainbow Health Center.

Surgery Scholarship. Community Kinship Life.

Sussman, R., et al. (2015, August 4). Discrimination and Denial of CareL The Unment Need for Transgender Health Care in South Los Angeles. St. John’s Well Child and Family Center.

Transgender Health Program. St. John’s Well Child and Family Center.

Transgender Law Center. (2015). Quine v. Beard. Transgender Law Center.

Transgender Surgery Eligibility. The Reed Centre.

Vaginoplasty. Papillion Gender Wellness Center.

Wade, L. (Photographer). (2015). Diana Feliz Ortiz.