Emma Somers

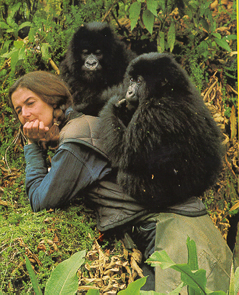

Dian Fossey was an American zoologist and anthropologist who studied the mountain gorillas of Rwanda from 1966 until her death in 1985. Fossey was part of the group known as the Trimates (or Leakey’s Angels), a group of three researchers assembled by Dr. Louis Leakey to study various primate groups throughout Africa and Southeast Asia: Fossey who studied the mountain gorillas of Rwanda, Dr. Biruté Galdikas who studied orangutans in Indonesia, and perhaps most notably, Dr. Jane Goodall who studied chimpanzees in Tanzania.

Rwanda is home to half of the world’s population of mountain gorillas, the other half spread throughout Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly known as Zaire). The mountain gorillas of Rwanda are threatened on numerous fronts. However, for the sake of my research project, I focused particularly on gorilla poaching and the commodification of gorillas on a global scale.

I have identified four main rationales behind gorilla poaching: “bushmeat” (meat from undomesticated animals) sale and consumption, ‘black magic’ rituals, ornamental decoration, and exotification through the sale of gorillas to foreign zoos. While these aspects are perhaps minor in the greater narrative of gorilla extinction, they provide an interesting contrast to the ways we typically think of conservation work. All of these rationales have deep ties to an Orientalist discourse of gorilla poaching and act as justification of conservation efforts and foreign intervention.

During her time in Rwanda, Fossey fought against gorilla poaching (often using rather unethical tactics of retaliation) and made significant strides towards species protection with her various conservation efforts. Fossey established the Karisoke Research Center in 1967, which remains to this day as one of world’s leading research institutes and centers of conservation for gorillas. My research project examines the complex ethical relationship between conservation and Orientalism through the case study of Dr. Dian Fossey.

Contextual Information of Themes

Mountain Gorillas

The mountain gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) is a subspecies of the more common gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) found throughout tropical African rainforests. The majority of mountain gorillas in the world today live in the Virunga Mountains that run along the borders of Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. An extinct range of volcanos, the Virunga Mountains provide a lush climate for the mountain gorillas that inhabit them between 8,000 and 13,000 feet in elevation (WWF). In 1970 there was an estimated mountain gorilla population of approximately 240 in total (Fossey), however, that number has steadily increased over the past half-century and today there are just under 1,000 (AWF).

Dr. Dian Fossey

Dian Fossey was born in San Francisco in 1932 to parents Kathryn and George Fossey. She graduated from San Jose State College in 1954 with a degree in occupational therapy, before moving to Kentucky where she worked as a children’s occupational therapist. In 1963, Fossey used what little money she had saved to travel to East Africa, where she first met Dr. Louis and Mary Leakey during a field exhibition in Tanzania. Despite having no professional or academic training in zoology or the study of animals, three years later, Dr. Leakey offered Fossey a position studying mountain gorillas in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Fossey spent only a year in the DRC before the ongoing civil war forced her to relocate her study to Rwanda where she would spend the rest of her time studying the mountain gorillas of the Virunga Mountains. In 1967, Fossey established the Karisoke Research Center in the heart of the Virunga Mountains where she would remain until her death in 1985. Today, Karisoke has become the world’s leading center for mountain gorilla study and conservation.

Orientalism

“A long tradition of what I shall be calling Orientalism, a way of coming to terms with the Orient that is based on the Orient’s special place in European Western Experience. The Orient is not only adjacent to Europe; it is also the place of Europe’s greatest and richest and oldest colonies, the source of its civilizations and languages, its cultural contestant, and one of its deepest and most recurring images of the Other. In addition, the Orient has helped to define Europe (or the West) as its contrasting image, idea, personality, experience. Yet none of this Orient is merely imaginative. The Orient is an integral part of European material civilization and culture. Orientalism expresses and represents that part culturally and even ideologically as a mode of discourse with supporting institutions, vocabulary, scholarship, imagery, doctrines, even colonial bureaucracies and colonial styles” (Said, 2-3).

Orientalism is a western view of colonized parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Orientalism, at the time of its founding, was used to both imitate, as well as depict, foreign lands through a western lens. Because these depictions of the Orient (‘East’) were being produced by the imperialist societies that dominated them, Orientalism served an inherently political purpose. Orientalism, essentially, became a way of thinking about foreign nations, particularly in the Orient. When viewed comparatively to western societies, Orientalism both exaggerates, as well as distorts, indigenous practices, traditions, customs, and cultures in order to serve a western agenda that reinforces western perceptions and prejudices. Through Orientalism, foreign places become exotic, uncivilized lands filled with danger and oppressed peoples in need of rescuing. Orientalism often serves as a justification of colonization and the many destructive tactics.

Analysis of Themes in Relation to One Another

Gorilla Poaching and Orientalism

While gorilla poaching, in reality, has little relevance or effect on mountain gorilla populations today, mainstream media’s hyperfixation on the illegal poaching of exotic animals exemplifies an invasive narrative based on Orientalist ideals. Through this narrative, conservation efforts by foreign organizations become justifiable. There are four main identifiable rationales behind gorilla poaching used within this specific narrative.

Bushmeat

The rise of mineral and resource extraction in parts of Africa has drastically impacted “bushmeat” sale and consumption, primarily throughout the southern half of the continent (Temperton). Hunting for bushmeat has primarily been driven by the proliferation of foreign companies occupying indigenous lands and creating an unsustainable rise in the population. Local communities are then coerced into exploiting the same resources they depend on. Not only are these companies destroying the natural habitats of human beings and wildlife alike, but they are destroying cultures and lifestyles in the process, a common tactic used in colonization and a justification for “white saviorhood.”

Wildlife in areas such as the Virunga Mountains are killed either by live ammunition or are snared in traps set by poachers. Although gorillas are often not the intended victims of these traps, there have been many cases in which gorillas have been snared accidentally. Given their significant strength and dexterity, gorillas are often able to break free from the traps, but fall ill to disease from the injuries sustained in the process (Fossey).

Black Magic

“Poachers were frequent users of sumu, probably because many of their black magic ingredients came from the animals and vegetation of the forest. With courage bolstered hashish, they killed silverback gorillas for their ears, tongues, testicles, and small fingers. The parts, along with some ingredients from an umushitsi, were brewed into a concoction reputed to endow the recipients with the virility and strength of the silverback” (Fossey, 35).

The attention to so-called ‘black magic’ in Rwandan society (as well as throughout much of Africa) has an interesting history that is deeply tied to Orientalist ideals toward indigenous cultural practices. For example, former Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana was accused of performing ‘black magic’ rituals using a three-hundred-pound python in order to maintain his two-decade-long rule over the country (Rosen). As can be seen time and again throughout the history of colonization, indigenous practices become demonized through the limited scope of a western lens. Scholar Rosalind Hackett notes that the way in which we view African countries “[is] predicated on the demonization of the feared other…the campaign to limit, if not eradicate, “traditional” forms of beliefs and practice in many parts of Africa” (Hackett). Using ‘black magic’ as a justification for foreign intervention therefore presents many problems in and of itself and reinforces the ‘othering’ mentality fundamental to Orientalism.

Ornamental Decoration

“Gorillas, silverbacks in particular, were also killed for their skulls and hands. The grisly trophies were sold either to tourists or resident Europeans in nearby towns of Ruhengeri and Gisenyi for the equivalent of about $20” (Fossey, 35).

While the sale of gorilla bodies is illegal, the hidden-market industry for exotic game is notable. There are significant ties between game hunting and toxic notions of masculinity that frame much of this illegal industry. Hunting, in general, is a male dominated ‘sport’, akin to military service (with a similar fixation on guns and death). Western societies have differing ideals about what it means to “be a man” than many indigenous societies, which helps to explain this hyperfixation. The collection of animal bodies, sometimes combined with ‘the thrill of the hunt’, allows men the “illusion of masculinity being chased” (Samuels).

It can therefore be surmised that ornamental decoration (with the use of exotic animals) is a direct result of contrived notions of masculinity within an imperialist society. This notion is then instilled on indigenous communities through the process of consumption. Local Rwandan communities are able to profit off of the western fetishization of exotic animals and therefore become participatory players in this industry, whether out of want or necessity. It becomes a matter of indigenous people exploiting their resources and lifestyles for the benefit of western markets.

Exotification

The sale of gorillas to foreign zoos is a multi-faceted industry. Gorillas are taken out of the wild for a variety of reasons, whether it be under the guise of rehabilitation, species conservation efforts, external study, etc. However, many of the animals raised in captivity do not survive when rehabilitated back into the wild, primarily due to a lack of familiarity of their environment. Zoos do not provide native flora/fauna or proper climates for these animals which hinders their acclimation to their native environments when released. Even when kept in captivity for the entirety of their lives, animals typically live shorter lives than they would in their own environments.

Young mountain gorillas have been taken from their families and sold to foreign zoos throughout North America, Europe, and Asia (Fossey). Zoos thrive on the exotification and rarity of non-native animals and create an almost tourism-like industry. Even the term ‘exotic animal’ becomes sensationalized to the point of fetishization. The relocation of mountain gorillas to foreign zoos reinforces classic Orientalist beliefs that indigenous people are incapable of taking care of themselves nor the land and resources they live on.

Other

Other factors that affect gorilla populations worth mention include: loss of habitat due to cattle/livestock grazing, agricultural expansion, resource extraction (specifically, charcoal used as fuel), and human conflicts (WWF). These factors affect the mountain gorilla population of the Virunga Mountains disproportionately more than poaching, however are ultimately negated within mainstream media’s portrayal of this species threat of extinction. Gorilla poaching becomes sensationalized through the lens of an Orientalist discourse.

Ethical Conservation

With the contention between Orientalism and conservation, it becomes important to examine the work done by Dr. Fossey with the mountain gorillas of Rwanda in a new context. It is not an exaggeration to assert that without the “active conservation” efforts of Dian Fossey, the mountain gorilla would be an extinct species (Rimmer). However, neither can we negate the ethical and moral dilemma of recognizing an ultimately detrimental Orientalist framework that encompasses the practice and justification of conservation work.

Karisoke

Fossey accomplished a number of goals while living in Rwanda and during her time spent studying the mountain gorillas of the Virunga Mountains. Fossey’s contributions to the scientific community were unprecedented at the time of their discovery, especially given her identity as a woman with little experience in a male-dominated field. Mountain gorillas were only “discovered” by Europeans in the beginning of the twentieth century and so very little was known about the species when Fossey began her work in the 1960s. The thousands of hours Fossey spent in the field studying the behaviors and familial organizations of the mountain gorillas led to significant advances in our understanding of the great apes and their closeness to human beings.

Fossey worked with the local communities she lived with to provide the most secure environment for conservation she could. Before leaving the DRC, Fossey learned how to track gorilla families from the local Congolese men she worked with, and then taught her new colleagues at Karisoke these same skills. Because of the civil wars throughout much of Central Africa at the time, government spending was used to fund the militaries, and the national parks suffered. Underfunded and lacking supplies, park officials were more inclined to take bribes from poachers and farmers that wanted to use the land to hunt and graze livestock.

Fossey often wrote about the problems between uncompromising conservation goals and the responsibility of respecting indigenous peoples’ right to their land (Fossey). The issue was less about the land historically belonging to indigenous people, but rather the deforestation caused by foreign logging companies and civil conflict causing forced migration higher into the mountains onto previously unutilized land. Human and gorilla habitats were greatly changing, along with changes in population growth. However, Fossey used what connections she had with the United States scientific community to secure funds for the park (including compensation for the park staff who worked there) which greatly reduced the bribes being taken. Since its founding in the Virunga Mountains, the park has been relocated to the nearby town of Musanze (Gorilla Fund). Today, Karisoke is funded by the Rwandan government and run primarily by local people. Students from across the world come to study and volunteer at the Center and continue researching the mountain gorillas.

Despite the notable efforts by Fossey to work with the local communities to ensure the protection of the mountain gorillas, there is certainly a significant portion of her work that is considered to be controversial. Fossey supported those who supported her and terrorized those who (at least in some part) unwillingly participated in the Orientalist framework outlined. Fossey would use what she called “active conservation” tactics to ensure the safety of the mountain gorillas she sought to protect. These tactics involved chasing cattle off of the reservation and confusing herds, frightening poachers using a contrived form of ‘witchcraft’, and taking the children of poachers left in villages back to Karisoke until the poachers came to get them. Government officials were also angered by Fossey’s continued ‘activism’ and refused funding for the park for many years. On the morning of December 27th, 1985, Fossey was found dead in her cabin with significant trauma to her head from a machete. Critics speculate that Fossey’s “active conservation” ultimately led to her murder, although the case has never been solved (Hayes). Fossey carried out atrocious acts for the mountain gorillas she loved in the name of conservation, and inadvertently contributed to the perpetuation of an Orientalist narrative by doing so.

Future Considerations

Dian Fossey’s contribution to the scientific community and the mountain gorillas of the Virunga Mountains has significant importance. However, this case study lies within a broader narrative of the ethical concerns regarding conservation work and the history of Orientalism. Fossey’s work provides two perspectives for this dialogue: one in which indigenous people take ownership over the autonomy of their land and the native species that live there, and another in which they are unjustly blamed for the possible extinction of local species. In no way is this research project meant to belittle, overlook, or condone the actions Dian Fossey took to ensure the species preservation of the mountain gorilla. But it is also difficult to condemn the entirety of the work she did and dismiss the measures she took to support the local community she lived in or label it merely as ‘white antics.’

Similar to the academic disciplines of anthropology and geography, conservation efforts need to be viewed and practiced through the perspective of indigenous people. Conservation work can no longer be defined by the demonization of Africans and the myth of “white saviorhood.” Conservation needs to include those most dependent and impacted by the environment they live in. This case study provides a unique framework to consider and reshape in order to meet the needs of communities where conservation work becomes a necessary part of life.

Sources

A.M. (2016, May 6). Man down: Hunting a new model for masculinity. The Economist.

African Wildlife Foundation (2017). Mountain Gorillas. AWF.

BBC (2016, August 30). The dark side of Uganda’s gorilla tourism industry. BBC.

Cara, Elizabeth (2007, April 1). An Example of Occupational Coherence: The Story of Dian Fossey, Occupational Therapist and Primatologist. British Journal of Occupational Therapy.

Fossey, Dian (2000). Gorillas in the Mist. New York, NY: Mariner Books.

Goodavage, Maria (2012, October 12). Gorilla Poaching: The Sad, Savage Reality. Take Part.

Gorilla Fund (2017). Dian Fossey. Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International.

Hackett, Rosalind (2013, January 7). The Politics of Religious Freedom: Traditional, African, Religious, Freedom. The Immanent Frame.

Hayes, Harold (1991). The Dark Romance of Dian Fossey. United Kingdom: Corgi.

Ingram, David (2000). Green Screen: Environmentalism and Hollywood Cinema. Chicago, IL: University of Exeter Press.

Kasnoff, Craig (2017). Mountain Gorillas: And Endangered Species. Bagheera.

Rimmer, Brandy (2013). Dian Fossey’s Controversial “Active Conservation” Proves Useful in Increasing Mountain Gorilla Awareness. Earth Common Journal.

Rosen, Jon (2014). In Rwanda, a tour of disaster. Roads and Kingdoms.

Said, Edward (1978). Orientalism. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Temperton, James (2016, July 12). Gorillas are being killed and eaten by miners in the Congo. Wired.

World Wildlife Fund (2017). Mountain Gorillas. WWF.