Kela Hall-Wieckert

Naomi Klein’s chapter entitled “Trading Pollution” in This Changes Everything (2014) piqued my interest because of its fascinating portrayal of a new and sinister problem I had never seen before. Conservation is being capitalized, commodified, and subsequently exploited for the benefit of large corporations polluting the Earth through convoluted and complex mechanisms that push this obscuring of conservation ahead.

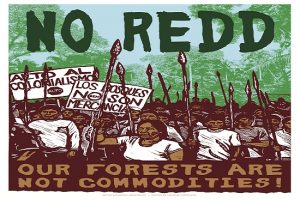

My project will focus on just one mechanism used, specifically carbon trading through Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, or REDD+. This United Nations led program’s “overall development goal …is to reduce forest emissions and enhance carbon stocks in forests while contributing to national sustainable development” (UN-REDD Programme).

Conservation has a long and turbulent relationship with capitalism and an increasingly problematic relationship with capitalist neoliberalism. Büscher and others (2014), a leading source in my research, work to delve into this new relationship they call NatureTM.

Neoliberal Conservation and the Green Economy

Capitalist development, originating in 16th and 17th century Europe has, through colonization, spread like a virus into the Global South and centered on changing the modes of production, circulation, application, and consumption for the good of the oppressor (Büscher, Dressler, & Fletcher). In contrast, neoliberalism as a model diffused in the 1970s and refers to the implementation of practices that “aim to replicate capitalist market dynamics across the social and public landscape” (Büscher et al., 4).

It is important in academic research not to muddy the definition of neoliberalism as the term often times becomes ambiguous and confused with mere capitalism. Neoliberalism as a trend is defined by extreme deregulation and less state oversight over political and economic affairs involving private organizations and “reliance on the ‘invisible hand’ of the market to efficiently allocate resources across the social landscape” (Büscher et al., 4). The processes that move this trend along include decentralization of power, deregulation, marketization of industry and services, privatization of services and land, and commodification of goods and services. Capitalism and neoliberalism are therefore not the same, even though they do incorporate similar mechanisms and ideologies and rely on similar principles.

The modern field of conservation has taken a new turn that parallels the rise of neoliberal capitalism. This relationship creates concomitant mechanisms that include carbon trading (see Carbon Trading), carbon offsets, synthetic biology, bioenergy, agrofuels, and payment for ecosystem services (PES). As public funding for conservation becomes scarcer and scarcer, neoliberal privatization tactics begin to surface. And as the biodiversity of our world becomes more and more threatened with climate change, policymakers insist that we must take innovative approaches that combine conservation and “the market,” thus economically incentivizing conservation (Büscher et al.).

This concept is generally referred to as the “green economy.” This new economy leaves many in the dust, especially Indigenous communities around the world. Through the appropriation of land for environmental ends, commonly referred to as green grabbing, new environmental markets are created for the benefit of private corporations and corrupt governments. Green grabs support the global green economy. As I will explain further, putting a quantified and economic value on nature is incredibly problematic, especially for projects relying on relationships with Indigenous communities such as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+).

What is REDD+?

REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation) is a forest policy mechanism classified under carbon crediting and PES, payments for ecosystem services (Global Justice Ecology Project). The essential idea of carbon crediting is to commodify both emissions and sequestration of carbon (Hall). As an example of carbon offset crediting on a smaller and more personal scale, airline companies frequently give the option of reducing one’s carbon footprint by purchasing carbon credits for an additional fee. In reality, the purchaser of the carbon credits is not the one doing the ‘carbon footprint’ reducing. Instead, they are paying for someone else, perhaps 1,000 miles away in a standing forest, to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions (Kaye).

In the case of REDD+, forests acting as carbon sinks and absorbing CO2 (carbon dioxide) from the atmosphere via photosynthesis are maintained and protected in order to offset the burning of fossil fuels and subsequent CO2 emissions elsewhere, likely by large, private corporations. Carbon sequestration, in which natural or artificial processes such as photosynthesis remove CO2 from the atmosphere, is more quantifiable than any other ecosystem service; this makes it the most popular ecosystem service to commodify (Hall). CO2 traded and sold on the carbon market can produce large amounts of income while, in theory, mitigating climate change. Thus, carbon crediting and mechanisms such as REDD+ have become popular, economically incentivizing conservation and development policy options in recent years (Hall).

So who trades and sells CO2 sequestered by forests on the carbon market? Corporations of the Global North are allowed to continue polluting by trading and purchasing emissions on the carbon market. In the case of REDD+, corporations purchase trees to offset their pollution from those overseeing the protection and maintenance of forests. These ‘overseers’ are various players, including governmental institutions, the United Nations and various NGOs (Hall). In order to better understand REDD+ and its relationship with neoliberal conservation, we must first understand its history.

The History of REDD+

Anthony Hall (2012), a central resource in what follows, studies REDD+ in Latin America and outlines the history of REDD+. In 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, international negotiations under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) began in order to set common goals for stabilizing greenhouse gas emissions. The UNFCCC implemented the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 and committed the European Union (EU) and 39 industrialized countries to cap greenhouse gas emissions 5% lower than levels in 1990. The Kyoto Protocol introduced a new mechanism of “cap-and-trade” that allows countries to go above and beyond their specified greenhouse gas emission levels by selling and trading on the carbon market with other countries that have accumulated emission permits (Hall).

An intergovernmental organization at the UNFCCC called “Coalition for Rainforest Nations” lobbied for economic support for the maintenance of standing forests as a key path to mitigating climate change. They pointed to the fact that deforestation is responsible for approximately 18% of global CO2 emissions. Under pressure from this coalition, REDD was introduced as both a financial compensation to ‘developing’ countries in the Global South and as a way to maintain standing forests. Under the original REDD policy (the addition of the ‘+’ later specifies the implementation of carbon enhancement stocks), members of forest communities were given financial incentives for protecting and preserving the forests. The UNFCCC set up a REDD+ Partnership that encompassed 70 nations including almost all Latin American countries. The Green Climate Fund in partnership with the World Bank would secure allocations of funding for future projects. Currently, a large assortment of REDD+ projects exist globally, the World Bank as well as the UN and Norway. The private carbon market makes up a large amount of funding as well (Hall).

Criticisms of REDD

Numerous complications exist in REDD+ projects. Hall summarizes these complications as the following: underestimations of forest systems’ complexity, diversity, variability, and political importance; numerous problems surrounding the effectiveness of reducing CO2 emissions; and, lastly, neoliberal assumptions about the communities (especially Indigenous communities) that live within the forests and their level of interest in neoliberal conservation projects.

Oftentimes REDD+ projects do not take into account the social diversity of forest communities, especially those in the Amazonian rainforest. ‘Cookie-cutter’ REDD+ models rarely work because forest use varies from community to community, and changes over time. Community decisions about maintaining forest cover in relation to agricultural patterns varies and are not predicted with analysis (Hall). And with the additions of REDD+ projects, forest practices will change considerably, leading to loss of intrinsic value and traditional knowledge. This makes forest practices even more difficult to predict (Dhandapani). REDD programs often reduce the biodiversity of slow-growing forests by cutting them and replacing them with monocrop plantations of fast-growing tree species (Lohmann).

Many complications reduce the effectiveness of REDD/REDD+ projects to minimize deforestation, create carbon stocks, and reduce emissions exist. These broadly include what Hall defines as “leakage, additionality, and permanence” (74). He defines leakage as the displacement of deforestation to other forest regions not protected under REDD+ projects. Monitoring and disrupting leakage requires complex surveillance that many REDD+ projects fail to implement (Hall). Additionality is defined as the failure to prove emissions reduction. Many PES projects such as REDD+ assume benefits rather than work to prove them. Extensive and costly data analysis is required to actually prove the effectiveness of REDD+; most projects do not invest in such analysis (Hall). Some even suggest that REDD+ ultimately fails as an emissions-reducing program considering forests can only uptake one of the six different greenhouse gases (Dhandapani). The issue of “permanence” revolves around how effective REDD+ projects are in sustaining deforestation and emissions reduction. Hall explains that there is no way to predict future variables such as “commercial pressures from logging, mining, and agricultural interests” (75).

Most importantly, attaching economic value to ecosystem services such as forest sequestration is yet another form of commodification. This gives forests a scarcity value (the increasing of a commodity’s price based on its low supply) that did not exist before and makes it a tradable item. The commodification and trading of forests through REDD+ is essentially an example of the Coase theorem in which trading can seemingly offset the externalities associated with a fossil fuel-based economic system. REDD+ is also based off the popular public policy tactic in which pressure is put on individual behavior change through economically stimulating cash payments rather than regulating corporate behavior (Hall).

Gustavo Castro, director of the NPO Otros Mundos Chiapas, perfectly summarizes the absurdity of this tactic: “They make it a business based on the notion that, ‘I’m not going to reduce CO2 emissions, instead, you are going to act as my carbon sink'” (as quoted in Global Justice Ecology Project). Putting pressure on behavioral change of individuals in forest communities instead of on the corporations polluting simply does not work, as found in a study by Sunderlin and others (2014) that analyzed 23 different REDD+ initiatives. Based on their site level research, behavioral change of forest practices by forest users will never be the solution to greenhouse gas emissions (Sunderlin et al.).

This tactic proves especially problematic when applied to the forests of Indigenous communities. Presumptively assuming that cash payments stimulate behavioral change in regards to forest use is based on Western views of society that do not cover everyone. Cultural beliefs on the intrinsic value of nature not captured by economic value is not considered when placing importance purely on cash payments. John Gowdy (2008), a professor of Humanities and Social Science, explains that climate change policy in general places too much importance on “narrowly rational, self-regarding responses to monetary incentives” (as cited in Hall). This Coesean model leaves out the traditional and moral sentiments of Indigenous views on the value of nature.

REDD and Indigenous Communities

Many REDD+ players claim that their projects benefit Indigenous communities, presenting them as win-win solutions to conservation and development (see Garibay & Edouard; UN Environment; Garzón). This is unsurprising considering as much as 70% of the forests REDD+ monitors are located in Indigenous territories (Hall). In reality, REDD+ projects merely work to exploit and devalue the rights of Indigenous communities in order to continue the burning of fossil fuels and further its neoliberal scheme (Dhandapani). Any project to combat deforestation and climate change that disrespects and destroys the rights of Indigenous communities is a false climate solution. The only true solution to deforestation is to protect the sovereignty of Indigenous nations and their collective land rights, regulate fossil fuel burning by private corporations, and change the behavior of consumption in the Global North (Fern). “Red-washing” of REDD+ projects, the undermining of Indigenous rights such as land tenure rights, is shrouded under the mask of conservation and development. This is especially seen in the context of REDD+ projects in Latin America.

Red-Washing

After reading and watching numerous sources directly from REDD+ players (the UN, NGOs, etc.), a common theme of “red-washing” surfaced. Red-washing is defined as “the deception of the general public by government and industry in trying to cover up their theft of Indigenous peoples lands, natural resources and cultural riches by pretending that they are acting in the best interests of the native peoples” (Wonders). The common eye generally is unable to see the neoliberal scheme underneath the purported guise of REDD+ projects, conservation of forests and the economic development of forest communities.

One video from the UN especially stood out to me as an example of red-washing. In June 2014, the UN Environment agency published a video promoting its projects in Ecuador. This video served to red-wash UN-backed REDD+ efforts in Ecuador by emphasizing how the traditional system of chakras was incorporated into the regulations of forest practices of local community members. Cocoa chakras are a traditional Ecuadorian agroforestry system proven to sequester higher levels of carbon than other systems such as cocoa paddocks and monocultures (Torres, Maza, Aguirre, Hinojosa, & Günter). The video claims to implement traditional practices by ‘incentivizing’ chakras over logging (UN Environment). It steers conversation away from the fact that REDD+ projects force behavioral change of local community members instead of reducing fossil fuel burning elsewhere. Emphasizing the seemingly positive side of REDD+ projects, such as implementation of traditional agro-forestry practices, masks the reality of the projects. It especially masks the fact that many REDD+ projects undermine the land tenure rights of Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous Land Rights

Another problem with REDD+ projects is their challenge to develop an informed land tenure system. The success of Coesean models like REDD+ requires clearly defined property rights (Hall). In reality, REDD+ projects partner with many Indigenous communities (especially Amazonian communities) that do not possess delineated, private landownership. Indigenous communities must decide whether to protect their lands from governments that may undermine their sovereignty by providing access to traditional regions or to retain their practices of communal land ownership. Despite their claims, REDD+ projects do not strengthen or create land tenure rights. Instead, REDD projects increase the risks of government and state ownership of traditionally Indigenous forests, as I discuss further in the case of the forests of Ecuador (Fern).

This problem of loss of sovereignty is acute in Latin American countries where governments own approximately 43% and private entities own approximately 32% of forests. Communities and Indigenous peoples manage approximately 25% of forests, with only 7% of these forests recognized under law (Hall). Currently, Indigenous communities in Latin America are resisting destruction, displacement, and appropriation of their “territorial integrity,” while at the same time sharing innovative solutions to environmental degradation and climate change (Punzano & Tucker). I used Ecuador as a case study for understanding how REDD+ functions and effects Indigenous communities.

REDD+ in Ecuador

Ecuador holds a long and tumultuous relationship with neoliberal conservation tactics and resource extraction. This relationship plays out in the territories of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples of Ecuador, where the forests they occupy hold deep meaning and value outside of western views of the economic value of nature. Each community holds different cosmovisions, defined as communal understandings between the interactions of life world, and cosmos (Dankelmon). In a 2012 video calling for direct action against oil extraction in territories of the Sarayaku Indigenous community, a community member explains, “The rainforest is the source of our lives, our culture, our medicines, our ancestral knowledge, and is a source of life for the entire human family” (quoted from El Nawal). REDD+ projects deemed as conservation threaten both the territory of Indigenous communities and their cosmovisions. One such project is entitled Socio Bosque.

Socio Bosque

Julianne Hazlewood’s dissertation entitled, “CO2lonialism and Hope in the Northwest Pacific Frontier Territory-Region of Ecuador” (2010), is a core resource for what follows. Her research focused heavily on the REDD+ readiness program Socio Bosque, and its effects on Indigenous territories in the coastal Esmeraldas province of Ecuador. Socio Bosque is an Ecuadorian government-run, incentive-based program that was designed to supposedly protect ecosystem services and pay forest communities for conservation. Socio Bosque was not explicitly a PES program, but rather a “conservation incentive” program. Such incentive programs mean that Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities protecting forests are not directly paid for their work. Instead, their work is “incentivized” by the Ecuadorian government (Hazlewood).

While Socio Bosque did not initially start off in partnership with the UN-REDD Programme, it held key similarities from the beginning, i.e., giving “economic incentives for farmers and indigenous communities” (as cited in Amazon Watch). Recently, Socio Bosque has increasingly partnered with the UN-REDD Program, a cause for serious concern as this could potentially increase the undermining of Indigenous land tenure rights (Amazon Watch). Most of the Indigenous nations in Ecuador are under contract with Socio Bosque, including the Shuar, Kichwa, Sapara, Cofan, Siona, and Shiwiar in the eastern Amazonian region, Chachi on the northwestern coast and several different Afro-descendant communities and montubio communities (Amazon Watch). Montubio is an Ecuadorian hybird identity of Spanish Indigenous ancestors communities (Roitman).

To the Coast: The History of Socio Bosque

Hazlewood delves into the Socio Bosque program in northwestern Ecuador and the history leading up to it. Socio Bosque originally stemmed from an experimental project entitled “La Gran Reserva Chachi” located in the Ezmeraldas Province in ancestral territory of various Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities on the northwestern coast of Ecuador (Hazlewood).

Until the creation of the Ibarra-San Lorenzo railway in 1958, these communities were geographically, politically, and economically isolated from the urban core of the country. In 1964, the National Institute of Agricultural Development in Ecuador began to allocate the Pacific forests inhabited by different communities into private parcels. Agriculture soon expanded into this region in order to benefit Ecuador’s export market sector. Deforestation soon began in the region with the onslaught of colonial settlement, road construction, and clearing for farms. Colonialists moving to the region displaced the Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities, undermining their cultural practices and way of life. In 1968, large concessions of forested land in the region were given to eight logging companies. These concessions still exist to this day (Hazlewood).

Deforestation became too rapid and extensive in the region, leading in 1981 to the Ecuadorian government enacting laws to halt specific logging techniques and introduce new ones. These laws ultimately failed as deforestation rates from 1983 to 1993 were higher for the Ezmeraldas Province than any other region in Ecuador. Deforestation prevailed throughout the 1990s and eventually led to the implementation of the project La Gran Reserva Chachi, and later Socio Bosque (Hazlewood).

The Chocó rainforest in Esmeraldas province, is considered incredibly important for the protection of biodiversity as more than 341 endemic species call it home (Hazlewood). Various NGOs, including the World Wildlife Foundation in partnership with the World Bank, imposed their conservation ethos onto the forest by deeming it a “biodiversity hotspot” worth protecting. Because of the immense biodiversity and natural resources of the region, numerous groups who rely on the region fight for its control. Afro-descendant and indigenous communities in the forest are continually pressured by corporations and NGOs through the capitalist market to either log the forest or to protect it for the good of the oppressor. The conflicting pressures to log and/or protect the forest makes for a contentious space that can undermine Indigenous and Afro-descendant rights.

Socio Bosque minimizes the power that Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities have over their traditional regions. This is done by creating contracts that deem their lands and natural resources as state-owned because of numerous clauses and articles in the Ecuadorian Constitution that allow for government-backed military intervention in indigenous territories if Indigenous nations economically develop their ecosystem services, considering ecosystem services are a “strategic resource” (Hazlewood).

Criticisms of Socio Bosque

Socio Bosque’s main problem is its reliance on the behavioral change of Afro-descendant and Indigenous individuals and communities which have been oppressed by colonialism for centuries. First, colonists forced control over the rainforest through the practices of clear-cut logging and agricultural clearing; now they require Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities to change to protect what is left over. Additionally, Socio Bosque fails to consider the cosmovisions of the Indigenous people with whom they partner. Describing the laws relating to Socio Bosque, Olindo Nastacuaz, the former president of the Federation of Awá Centers stated at a panel of conservation representatives in January 2009, “You people have different visions, other needs. You are from the city; I am from the countryside. There is another form of necessities and cosmovisions” (as cited in Hazlewood, 114). This perfectly encapsulates the underlying problem of REDD+ projects such as Socio Bosque. Indigenous communities who have lived for years in the changing landscape of their needs and the forest needs know better how to protect them than, frequently corrupt, governments, the United Nations, or NGOs.

The Ecuadorian government’s interests are further suspect and problematic as they not only oversee Socio Bosque but also oil extraction and agricultural projects that will likely conflict with and undermine conservation. One Ecuadorian governmental ministry manages and supports the expansion of palm oil plantations into Indigenous territories, another supports continued oil exploration in indigenous territories, while a separate one oversees Indigenous people’s conservation of their forests (Hazlewood). In an interview with Accion Ecológica, director of Socio Bosque, Max Lascano, stated:

Mining is part of the strategic resources of the State, of course. So with or without Socio Bosque, mining activities could occur if they are priorities of the State. So, yes, if it is strategic decision of the State, it is possible that in a Socio Bosque area, mining exploitation could occur.”

When the interviewer asked, “Or oil?” he responded with, “Yes, oil or mining” (translated from Accion Ecológica). The two-headed dog, one with “conservation” tattooed across its forehead and the other soaked in oil, rears its ugly heads.

Indigenous Resistance to REDD+ and Socio Bosque

Numerous instances of Indigenous resistance against REDD+ and Socio Bosque in Ecuador exist. Three examples of resistance are outlined below.

On August 3, 2009, the Confederation of Indigenous Peoples from the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE) issued a statement in direct opposition to REDD+ schemes. Tito Puanchir, president of CONFENIAE, declared the following as one of their resolves:

We reject the negotiations on our forests, such as REDD projects, because they try to take away our freedom to manage our resources and also because they are not a real solution to climate change, on the contrary, they only make it worse (Resolve, 4).

His statement points out that it is a false climate solution, as do many sources on REDD+ problems. The increasing urgency to address climate change with far reaching ideas presents many false solutions that in reality merely give an upper hand to corporations and corrupt governments.

In October 2012, the Ecuadorian government announced new oil concessions in the territories of Afro-descendant and indigenous territories that were included in Socio Bosque (Lang). At the same time, representatives of the Ecuadorian government failed to mention these new oil concessions while presenting on their REDD programs at the Ninth UN-REDD Programme Policy Board Meeting in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Lang). Indigenous leaders from the Shuar, Achuar, Shiwiar, Sápara, and Kichwa communities had already rejected oil concessions on their land; nonetheless the plan moved forward (Lang). Under various safeguard policies that UN-REDD holds, the Ecuadorian government, as well as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, are required to ensure that their projects do not in any way contribute to human rights violations of Indigenous peoples (Wiggins). The Indian Law Resource Center speaks to the irony that the Ecuadorian government is both creating oil concession contracts and contracts under Socio Bosque with Indigenous nations. They stated in their letter to the UN-REDD Programme Policy Board that, “For example…[w]hile the Sapara people have entered into a REDD contract with the Government of Ecuador to preserve their lands and biodiversity, the Government is now severely undermining that effort” (Wiggins).

In March 2015, hundreds of representatives from Indigenous communities in Ecuador met in the Parish of Macuma and declared their opposition to fossil fuel extraction and “the commodification of nature” in their territories. Within the declaration they “reaffirm(ed) their strong rejection of the Ecuadorian state’s policy on oil developments, mining, logging, hydropower and Socio Bosque [REDD] activities.” In direct resistance, they also made null and void all agreements between the government and individual communities rather than with the official leadership of Indigenous nations in Ecuador. They vowed to also “create a new economic development model utilizing renewable natural resources” (as cited in Zuckerman). The location of the Parish of Macuma held meaning because only a week earlier, the Secretary of Hydrocarbons, whose sole responsibility is “implementing the activities of signing, amendment, and administration of areas and oil contracts,” had visited a school in the parish to persuade Indigenous children that oil drilling was a good thing. Along with the declaration, they demanded the head of the Secretary of Hydrocarbons never set foot in their territory again (Zuckerman).

Do Solutions to ‘False Solutions’ Exist?

Though schemes such as REDD+ are presented as an answer to the increasing urgency of climate change solutions, they fail to do so in reality. This is because they fail to address the concerns of Indigenous communities and instead only work to benefit private enterprise and the continuation of fossil fuel burning. Instead of putting time and energy into false climate solutions such as REDD+, we must make an effort to uplift solutions coming from Indigenous communities. Below, I present the solutions posed by the Sarayaku Communities.

Solutions from the Sarayaku Communities

The town of Sarayaku is located in the Pastaza province in the Amazon region of eastern Ecuador. Sarayaku is composed of seven different Indigenous communities. Approximately 95% of their territory is classified as primary forest including incredible biodiversity. Their cosmovisions center on the “three essential ecological units: Sacha (Jungle), Yaku (rivers) and Allpa (land). Each one of these ecosystems sustains an infinity of flora and fauna, transcendent for the experience of the nationalities and Amazonian peoples” (translated from Sarayaku). The Sarayaku community presented the Kawsak Sacha (Living Forest) proposal in 2016 at Conference of the Parties (COP21) in Paris, France (Punzano & Tucker). Within their proposal, the Sarayaku community summarized the Living Forest as the following:

The entire world is peopled by beings that sustain our planet thanks to their way of living in continuous interrelation and dialogue. This vision is neither a quaint belief nor a simple conservationist ideal. It is instead a call to the people of the world to learn once again [and] to feel this reality in their very being. This metamorphosis will only be possible once we learn to listen to and dialogue with these other beings, who are a part of a cosmic conversation that goes well beyond the dialogue of the deaf until now carried out exclusively among us humans. Entering into this broader conversation with all living beings can be the foundation for a more sustainable economic life, one that is more respectful of Mother Earth. And it would be the basis of conceptualizing, building, and disseminating a genuine Kawsak Sacha in our world—a world that today is threatened by an ecological crisis of planetary proportions (Gualinga, 3).

As a concrete project, they propose that:

- Kawsak Sacha be recognized and provided legal protection and nationally and internationally;

- Sumak Kawsay (good living) achieved as an alternative economic model through “the three foundational pillars of…: Fertile Land (Sumak Allpa); Living in Community (Runaguna Kawsay); and Forest Wisdom (Sacha Runa Yachay);” and

- Jatun Kawsak Sisa Ñampi to demarcate through a border of flowering and fruiting trees “The Frontier of Life” of their “territory” to both themselves and those outside.

Solutions to ‘false solutions’ such as REDD+ do exist and are especially viable when coming from Indigenous voices. This is because they hold deeper understandings of the forests they live in beyond which any neoliberal conservation tactic could achieve. The recent shifting of conservation down a path paved with neoliberal schemes such as REDD+ will not be the climate change solutions we seek. Instead, we must uplift the voices of Indigenous communities such as those in Ecuador and begin to learn how to better achieve a relationship with nature that does not rely on economic incentives.

Sources

Acción Ecólogica (Producer & Director) (2010). Max Lascano: petroleo y mineria. Quito: Acción Ecólogica.

Amazon Watch (2011). Ecuador’s Forest Partner’s Program: An overview of Socio Bosque contracts with Indigenous communities. Amazon Watch.

Büscher, B., Dressler, W., & Fletcher, R. (Eds.). (2014). Nature™ Inc.: Environmental conservation in the neoliberal age. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Dankelmon, I. (2002). Culture and cosmovision: Roots of farmers’ natural resource management. Adaptive Management: From Theory to Practice in SUI Techincal Series, 3, p. 41-52.

Dhandapani, S. (2015). Neoliberal capitalistic policies in modern conservation and the ultimate commodification of nature. Journal of Ecosystem and Ecography, 5(2): 167.

El Nawal (Producer and Director). (2012). Call to Action from Sarayaku Indigenous Leaders. Ecuador: Sarayaku.

Fern (Producer and Director). (2012). The story of REDD: a real solution to deforestation? Brussels, Belgium: Fern.

Garibay, A.H., & Edouard, F. (2012). Tenure of indigenous peoples territories and REDD+ as a forestry management incentive: the case of Mesoamerican countries. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (E-ISBN 978-92-5-107503-6 (PDF).

Garzón, E. (2017, Jan. 6). Amazon Indigenous REDD+: an innovative approach to conserve Colombian forests? Mongabay.

Global Justice Ecology Project (Producer), & Calderón, M. (Director). (2012). A darker shade of green: REDD alert and the future of forests. Hinesburg, VT: Global Justice Ecology Project.

Gowdy, J. (2008). Behavioral economics and climate change policy. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68, pp. 632-644.

Gualinga, J. (2015). Kawsak Sacha-Living Forest. Sarayaku.

Hall, A. (2012). REDD gold in Latin America: Blessing or curse? In Haarstad, H (Eds.) New political spaces in Latin American natural resource governance (pp. 61-82). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hazlewood, J.A. (2010). Geographies of CO2lonialism and hope in the Northwest Pacific frontier territory-region of Ecuador. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky.

Kaye, M. (2012). Combating climate change on credit. Al Jazeera.

Klein, N. (2014). This Changes Everything. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Lang, C. (2012, Nov. 6). Ecuador’s conflict between oil extraction, indigenous rights and REDD. REDD Monitor.

Lohmann, L. (2006). Carbon Trading: A Critical Conversation on Climate Change, Privatisation and Power. The Corner House.

Puanchir, T. (2009, Aug. 3). CONFENIAE rejects all kinds of environmental negotiations on forests and extractive policies that damage the territories of the Amazonian indigenous nationalities and peoples of Ecuador. Confederacion De Nacionalidades Indigenas De La Amazonia Ecuatoriana.

Punzano, A., & Tucker, J. (2016, Oct. 16). Amazonian communities at the front line against climate change. Open Democracy.

Roitman, K. (2008). Hybridity, Mestizaje, and Montubios in Ecuador. Queen Elizabeth House Working Paper Series. Oxford, UK: Queen Elizabeth House.

Sarayaku (2017). Original Kichwa town of Sarayaku. Sarayaku.

Sunderlin, W.D., Ekaputri, A.D., Sillis, E.O., Duchelle, A.E., Kweka, D., Diprose, R. . . . . Toniolo, A. (2014). The challenge of establishing REDD+ on the ground: Insights from 23 subnational initiatives in six countries. Occasional Paper 104. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR.

Torres, B., Maza, O., Aguirre, P., Hinojosa, L., & Günter, S. (2015). The contribution of traditional agroforestry to climate change adaptation in the Ecuadorian Amazon: The chakra system. Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation, 3. pp. 1973-1994.

UN Environment (Producer), & Ministry of the Environment, & UN-REDD Programme (Directors). (2014). A forest of opportunities in Ecuador. Nairobi Kenya: UN Environment.

UN-REDDE Programme. (n.d) How we work. UN-REDDE Programme.

Wiggins, A. (2012, Oct. 26). Letter to co-chairs of the UN-REDD Programme Policy Board. Indian Law Resource Center.

Wonders, K. (2008). Redwashing. First Nations: Land Rights and Environmentalism in British Columbia.

Zuckerman, A. (2015, March 3). Ecuadorian Indigenous movement unites in defense of territory. Amazon Watch.