Ashley Ward

The U.S. is experiencing largest wealth gap between the rich and poor since the Great Depression, growing at an accelerated rate since the 2008 financial crisis (Aquinas). Many jobs once seen as high school employment have become the main sources of income for grown adults with families; 75% of minimum wage laborers are adults and more than half identify in the census as women (Weber). While poor folks work two or three jobs on minimum wage to survive, corporations keep wages low and profits grow (New York Times).

Fast food and minimum wage earners have taken actions to demand pay raises and benefits for themselves and their families through strikes, unions, and demonstrations. Those that are most affected by the minimum wage are people living in impoverished areas, People of Color, Trans folks, and many other marginalized groups. Marginalized communities are also on the front lines of labor struggles.

Systemic control over gendered pay gaps, race disparities, class inequalities, and lack of job options for the poor dictate access to privatized resources. Workers have been organizing for a long time, but there has been an erasure of certain voices in labor movements. Migrants or undocumented groups face restrictions when trying to get a job, especially a job that pays a living wage. Prisoners face exploitation and human rights abuses but are often left out of the discussions around labor. Reproductive labor, which will not be discussed in depth here, continues to be devalued by capitalist patriarchal society in the U.S. Many question whether raising wages will benefit workers materially or threaten their job opportunities.

Higher Minimum Wage: Can it Save Us?

Some disagree that a higher minimum wage is a solution to poverty. There are some who think raising the minimum wage will restrict job access further and encourage or force more people to get on state assistance, but Democratic Governor of New York and possible 2020 U.S. presidential candidate, Andrew Cuomo, says that it would get low-wage workers off of assistance (Associated Press).

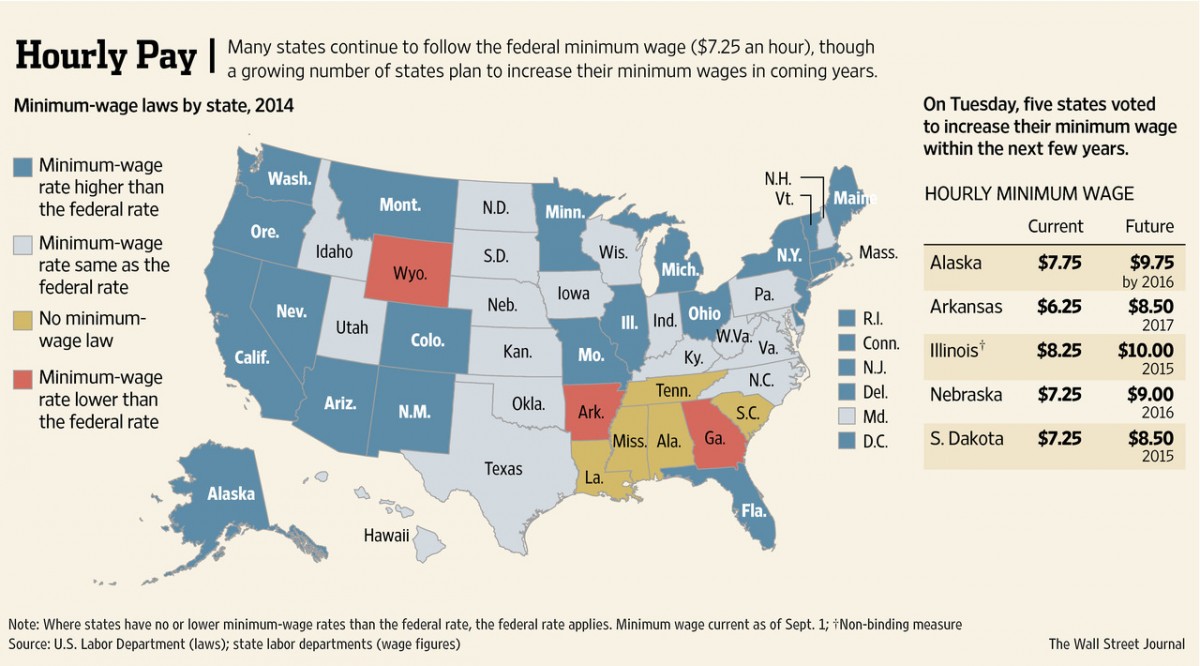

The federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour, and some states pay at or above that wage. Other states pay below minimum wage, such as Wyoming and Arkansas as shown on the map above. Many states are in the process of raising the minimum wage for workers, while others are maintaining the same wages.

Robert Mayfield owns nine Dairy Queen franchises in Texas and thinks that higher wages will cause him to raise prices on his menus. He believes small business owners would be forced to stop hiring people, hurting the job market and workers (Aubrey). Ken Jarosch, from Elk Grove Village, Illinois, fears that he has to raise wages or the workers at his bakery may leave and head to Chicago, where wages are higher (Rosenberg).

Other business owners support minimum wage, such as Kristin Kohn, who chose to raise wages for the workers at her gift shop on her own because she thinks valued workers are more productive (Rosenberg). According to a survey by The Hartford, about two-thirds of small businesses owners support raising minimum wage, and eighty-one percent pay higher than the minimum wage already (Rosenberg).

Although some groups call for a restructuring of the economy outside of capitalism in order to meet the needs of all people, they still generally agree that reforms that protect workers and families are better than nothing. Those who critique the ability for minimum wage to improve the material needs of workers also acknowledge that inflation of healthcare, housing, and other resources cannot necessarily be balanced out by higher minimum wages. There are also worries about access to jobs, even if they are paying more. Often these folks can be found in the streets protesting stolen wages and racist hiring practices, or organizing with non-business unions such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

Jonathan Lange, who organized with the living wage campaign in Baltimore 23 years ago, thinks a minimum wage raise can be successful through “organizing workers and building deep community alliances” (Lange). Campaigns may benefit workers’ movements, but what Lange promotes is a more localized grassroots movement that enables workers to have control over their own wages. If people are able to found and join unions, they may be able to work towards long-term gains for themselves and others through democratic decision making. Movements such as Fight for 15 often lack “worker participation, direct organizing, and popular democracy” that have made worker organizing successful in the past (Recomposition).

The Trump Administration and Working Class Worries

As President Donald Trump came into office, he proposed a flat 15% corporate tax rate, down from the 15%-35% current tax rate (Busler). Conservative business proponents rejected the idea that it “just another tax cut for the wealthy,” but workers have been struggling and protesting for wage raises and job stability for a long time (Busler). Many are feeling even more of a threat since the inauguration, because poverty wages often force communities onto state assistance. With fewer taxes for the rich, state assistance will more than likely be cut. The anti-immigration stance that Trump has taken threatens immigrants with deportation or imprisonment. Many migrant workers are fearing the loss of job access and stability that anti-immigration policies put forth.

Racism and Sexism: Labor Secretary Position

The Trump Administration nominated the CEO of Carl’s Jr and Hardees, Andrew Puzder, as Labor Secretary. Puzder has continually refused to support minimum wage raises, and maintains that fast food jobs are the majority type of job employing young people. Carl’s Jr. workers who are non-male experience high rates of sexual harassment in the workplace (upwards of 60%) (Taylor). In 2014 the Carl’s Jr. company was forced to fire over 1,000 undocumented workers after Immigration and Customs Enforcement raided stores all over the country (Rainey). Abuse allegations and the fact that he had hired an undocumented immigrant as a housekeeper as well as at his restaurants, made the Senate and the public unsure about having Puzder as Labor Secretary (Semuels).

In a 2015 commercial, Carl’s Jr. used half-naked women playing volleyball over the U.S.-Mexico border to advertise its “Tex-Mex Burger.” The women are sexualized and racialized, with “Mexican” women on one side of the wall and white “American” women on the other side; the ad makes light of immigration and erases the experiences of immigrants by using the border to make money. This was not the first time the company used race and gender to sell burgers.

Puzder’s nomination was met with large fast-food worker protests and resistance from the Senate. After a few weeks of demonstrations, Puzder withdrew his nomination in February 2017. Alexander Acosta was later confirmed as labor secretary.

The Fight for 15

The Fight for 15 in Washington, Massachusetts, California, and other states is the largest movement towards raising living standards for workers since labor union movements of the 1930s. It is pushing for higher wages and union rights for low-wage earners (Gonzalez). Most people involved say it started in 2012 in New York, when fast-food workers walked out in demand of higher wages during a one-day strike (Greenhouse). What began with pressuring fast-food restaurants has spread, with the hopes of encouraging more locations to call for a fifteen-dollar minimum wage.

The campaign has grown to include all low-wage earners fighting for $15 an hour, not just fast food employees. Federal minimum wage has not gone up since 2009, while in January 2017, inflation on consumer goods was higher than it had been in three years (Business Live). Successes credited to Fight for 15 have caused some states or cities to vote on raising the minimum wage to fifteen-dollars over the course of a few years; by 2020, Washington state should have a $13 minimum wage (Agogliati). As inflation goes up, the cost of living and the cost of resources increases as well—when wages stay the same, people struggle.

(Credit: Brennan Linsley/AP)

Some corporations have caved to the demands of Fight for 15, including McDonald’s and Wal-Mart, who have agreed to slightly raise wages (Aubrey). Lawsuits, formal complaints, worker walkouts and demonstrations are some tactics utilized to help Fight for 15 succeed. Organizers, such as Tim Wise from Missouri, have felt that pressuring presidential candidates and other politicians has had success. Wise thinks that workers taking to each other and sharing their work experiences makes labor movements stronger (Aubrey).

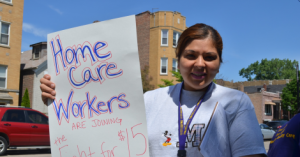

Caregivers and the Fight for 15

Home-care and child-care workers have joined in, such as Crystal Williams from Hartford, Connecticut. She says that she participates for herself as well as the parents of the children she provides care for: “I talk to parents, and I see that they have similar struggles with making ends meet” (Jones). On April 15, 2015, child-care, home care, and airport workers demonstrated alongside other low-wage earners (Zillman). According Mary Kay Henry, president of the Service Employees International Union who invests thousands of dollars into Fight for 15, says that parents need proper care for their kids when they work (Zillman).

Home care laborers, such as health aides, provide work that helps keep people’s family members “happy, healthy, and alive,” according to Elizabeth Johnsen whose mother is quadriplegic (Johnsen). Johnsen values the attention and labor that is required of caregivers, and she believes health-aides deserve better wages.

Intersections of Race and Wage

Immigrant Rights

On Columbus Day 2015, Fight for 15 organizers marched in Chicago with over two hundred “workers, students and activists,” as they protested “overt racism and xenophobia” in Donald Trump’s campaign (Marcetic). They marched with signs, chants, a mariachi band, and a large unflattering Trump piñata. The rhetoric that Trump uses represents modern colonization, according to Nicholas Chango, an Indigenous Incan descendant who attended the protest (Marcetic). Tyree Johnson, an organizer for Fight for 15 and for the anti-Trump protest, stated that, “Black and brown people are tired of being disrespected” when asked his reasoning for attending (Marcetic). Keeping wages low in communities of color benefits corporations and systemically keeps black and brown folks in poverty.

Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter and immigrant rights groups took the streets in November 2015, with the slogan “Economic Justice = Racial Justice = Immigrant Justice” (Gonzalez). Participants believe that Black Lives Matter and Fight for 15 should stand together because both movements involve communities of color. Single mothers, undocumented immigrants, and parents who had lost their children to police brutality were in the ranks of protesters (Gonzalez). Some wore sweatshirts that said, “I can’t breathe. Fight for $15,” in memory of Eric Garner, to bring attention to the intersections between race and class struggle in the United States (Gonzalez). The first to arrive were racial justice advocates (Shirodkar).

Challenging Systemic Racism

About 8,000 workers marched on the monument of Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Virginia during the first Fight for $15 national workers’ convention in Richmond, Virginia in August 2016 (fightfor15.org). They chose Richmond because it “was the capital of the Confederacy and displays ‘the enduring effects of racist policies that are holding back low-paid workers of color today’” (Rupcich).

Recent Achievements and Actions

Workers participated in protests at presidential debates across the United States in 2015 and 2016. Republican and Democratic debates were both targeted in an attempt to sway both parties towards a fifteen-dollar minimum wage.

Minimum wage was raised to a projected fifteen-dollars an hour over the course of a couple years in California and New York (Fight for 15). According to the Fight for 15 website, this lands ten million workers in the position to make fifteen-dollars an hour in the near future. By April 2016, 320 cities had participated in Fight for 15 actions—by May workers in Illinois had staged the largest series of demonstrations ever held at the annual McDonald’s shareholder meeting (Fight for 15).

In Seattle, Washington, in April 2015 the city voted to raise the minimum wage from $9.50 an hour to $11 an hour, working towards $15 an hour by 2017 for most workers (Bernstein). After many demonstrations and rallies by Working Washington, the Fight for 15 committee that focuses on only raising wages in Washington, mass voter support for raising wages grew. A study from the University of Washington in 2016 provided evidence that the fears business owners and consumers had of loss of jobs and inflation of products have not come to fruition. It turns out, most low-wage earners gained an increase in their income even if they faced a loss of hours, while Seattle’s economy grew at three times the national average (Bernstein).

In August 2016, the national workers’ convention was held in Richmond, Virginia, where the attendees vowed to continue fighting for a $15 minimum wage. What the Fight for 15 website does not talk about, however, is that there was an event at the convention that disturbed the atmosphere of trust in the Fight for 15 campaign.

SEIU and Fight for 15: Friend or Foe?

Fight for 15 organizers are outsourced labor employed by a business union called Service Employees International Union (SEIU), whose slogan is, “Families uniting to raise wages and achieve justice on all fronts” (seiu.org). The union claims to stand in solidarity with immigrant rights movements, healthcare for workers, and good jobs for all. Rallying people towards unions is beneficial for SEIU, because it collects union payments from all members and can steer members to engage with politics.

To avoid being the direct employer of Fight for 15 organizers, effectively dodging responsibility for providing a union and a $15 minimum wage, SEIU set up “worker center groups” and “organizing committees” (Redmond). These committees take millions of dollars of donation money every year from SEIU, and that money is used to pay Fight for 15 employees—it also allows SEIU to have power over the Fight for 15 movement (Redmond).

Worker committees are split up into eight verified labor groups, the Fast Food Workers Committee and the Child Care Committee among them (Baertlein & Layne). SEIU has proclaimed that Fight for 15 is “distinct from the union itself,” and therefore it should not have to provide union rights for those workers. SEIU has, however, invested at least $50 million into the campaign and workers’ committees—in 2015 the Fast Food Workers Committee received $3.8 million (Baertlein & Layne).

Business unions in the United States have issues when staff demand the same union protections as union members, and in the case of SEIU it has resulted in the creation of the Union for Union Representatives (UUR) (Resnikoff). UUR now represents about one hundred SEIU employees—they insist that Fight for 15 organizers should be unionized and paid a $15 minimum wage (Redmond).

A representative of UUR says that SEIU has been pushing anti-union feelings on the national organizing committee for Fight for 15, splintering the relationships between paid organizers and other low-wage workers (Gupta, 2016). There is hypocrisy in the refusal of SEIU to provide better wages and union rights to the people they employ, while campaigning for these rights for others.

Fight for 15 Paid Organizers Want a Union

Organizers came forward united under the Fight for 15 Staff Union Organizing Committee, created to help paid organizers fight for higher pay and union rights, at the first annual Fight for 15 convention held in Richmond, Virginia in August 2016 (Pratt). SEIU President Mary Kay Henry was speaking when the committee disrupted and approached the stage (Pratt). They attempted to hand Henry a letter asking for a $15 minimum wage as well as union representation (Redmond). Security got to the group before they could reach the stage, and “Henry stepped back as a group of African-Americans and Latino/as who sit on the national organizing committee for Fight for 15 stepped up” (Gupta, 2016).

Someone grabbed the mic remarked, “Are you serious? ….You guys get paid enough. You have a chance to get a union. I don’t” (Gupta 2016). The person speaking was of the opinion that paid organizers would never walk a day in the shoes of the underpaid workforce. Security became forceful with the Fight for 15 Staff Union Organizing Committee, shoving the group and tearing up their signs. The crowd of about 1,000 was also acting hostile and aggressive, chanting in the faces of organizers—eventually many had to jump over tables to get out of the area (Gupta 2016).

Fight for 15 Organizers Speak Out

Barajas-Ames, an organizer for Child Care Fight for 15, gets paid about nine-dollars an hour for a sixty-hour work week after she pays for non-reimbursed work-related gas expenses (Gupta 2016). Others have spoken out as well, saying that they generally come from poverty-wage backgrounds and continue to be low-wage workers as employees of Fight for 15. Organizers are often “ in the same position” as other minimum-wage earners according to Emiliana Sparaco from California Fight for 15, who takes home about $35,000 a year (Resnikoff).

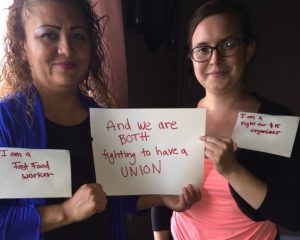

Paid organizers have formed solidarity with other low-wage earners in the Fight for 15, even though some people have been resistant. Emiliana Sparaco and Roselva Gomes, who works at Burger King, are just one example of solidarity between the two groups (Moberg). They stand together in fighting for union rights and a $15 minimum wage.

What Does SEIU Get Out of its Investments?

SEIU has always encouraged the idea that the Fight for 15 movement is powered and sustained by workers, but evidence exposes what seems like a deliberate attempt to control and manipulate workers into joining SEIU (Gupta,2013). The more people engaged in a discussion about unions and workers rights, the more people will sign up for union membership. In this case, workers sign up to be due paying members of SEIU, allowing space for the union to push members to vote for certain politicians, such as Hilary Clinton and Barack Obama.

Former organizers in New York and Chicago say that they knew all along that SEIU was “directing the campaign” as well as “funding the organizing”—the goal was always to organize low-wage earners (Gupta, 2016). Two former organizers say that they were hired by SEIU-funded worker committees, such as Action Now, to go to fast-food restaurants to rally workers behind a $10 an hour minimum wage (Gupta, 2016). Counter to the mainstream story of workers organizing themselves towards better wages, it appears that workers were rallied by SEIU. These reflections by former organizers reveal that the media analysis being presented to the rest of the world is not only inaccurate, but may be intentional.

Big Bucks Invested in the Fight for 15

Most news and media sources fail to acknowledge its role that SEIU plays in the Fight for 15. SEIU is a business union, and is liberal in its politics. In 2015 “tens of millions of dollars and counting” had been invested by SEIU into the Fight for 15 (Layne & Baertlein). It has continued to donate to the campaign into 2017. Though they say they are more “servant than shepherd,” there are unspoken benefits for the union that are swept under the rug (Gupta 2013).

People of color are most affected by minimum wage, and although SEIU behaves and publicizes itself as though it is in solidarity with racialized poverty struggles, it appears SEIU only lends financial support when it fits into their agenda. There are no statements about the staggering number of people of color killed by police, particularly in poor black communities, on the SEIU or Fight for 15 websites. In 2016, nearly 25% of the 1,092 people killed by police were black people, and nearly 15% were Latinx people—seems like something that should be acknowledged when claiming to stand in solidarity with immigrant communities and Black Lives Matter (The Guardian). SEIU cares about increasing membership from communities of color and garnering their support for political campaigns, but does the union actually care about deconstructing a racialized system that it benefits from?

SEIU Funds Candidates and Politicians

Although SEIU claims to be pro-immigrant rights, “the union spent more than any other outside group to elect Barack Obama,” who engaged in the largest deportation effort of any president in the U.S. to date (Beyerstein). It pledged to invest $70 million into Clinton’s presidential campaign in 2016 (Miller).

SEIU President Mary Kay Henry says that SEIU supported Clinton because “communities of color and white women are difference-makers,” and the union is interested in mobilizing that voting force (Miller). There is a connection between SEIU claiming it wants better working conditions for people of color and their intentions with politics. The more communities union leaders they can get to join their union, the more ease they will have in “persuading members to vote as unions want them to” (Wall Street Journal).

Outside of Fight for 15

A Day Without Immigrants

In February 2017, a general strike was called for immigrants and their allies to stay home from work and school, as well as to avoid purchasing anything. Called “A Day Without Immigrants,” the movement attempted to challenge the anti-immigration policies of President Donald Trump. The protests and walkout gained online support and encouraged non-U.S. born people to refuse to benefit the economy for one day (Rodionova).

“Most people who come to America are just working,” says Fernando Garcia, an owner of a solar fan operation (Ax). He closed his doors on the day of the protests in support of migrant workers. People migrating to the United States are generally coming for jobs to provide for themselves or their families, while anti-immigration laws are imprisoning people, separating families through deportation, and criminalizing immigrants and undocumented communities. Restaurants were closed down in Washington D.C. (even at the Pentagon), Minneapolis, Boston, and other ciites, while rallies and protests took place across the United States and students walked out of classes (Ax).

In response, owners and bosses fired more than one hundred workers who participated in the “Day Without Immigrants” protest, including twenty workers at Bradley Coatings in Tennessee (Rodionova). Jim Serowski, founder of JVS Masonry in Colorado, told the workers that if they were going to participate they would have to face the consequences of that decision; when thirty laborers did not show up for work they were fired “with no regrets” (CNN Wire). Serowski claims that he has long supported “these people” as well as immigrant labor and justified his actions by claiming the walkout had harmed his business. Six of the Latinx immigrant workers have expressed that the loss of their jobs was unfair and they were not expecting to lose their income because they stood in solidarity with other immigrants (CNN Wire).

Below, a video from The Young Turks goes into more details about workers across the U.S. fired for missing work during the demonstrations.

Luis Mora, from Nevada, says that he supported the protests but was unable to participate because he needs the money: “Always I work hard, I work hard for my money. I take care of my family. I have two sons, and I have my ex-wife and I support my mom.” Walking out would have hurt those closest to him before hurting the companies that profit off of immigrant labor and low wages, but he thinks that longer more sustained actions could really shed light on the work that immigrants do in the United States (Herbets).

Making any sort of blanket statements about immigrants rights or what immigrants want can erase the many diverse voices and opinions of different communities. Not all immigrants agree on what they want or how they want to achieve their goals, which is the same for any movement. Movements should be valued when they make space for dissent and disagreement, and questioned when they are over funded and pushed towards an agenda they have had no say in.

A Day Without Latinos

Immigrant communities in Milwaukee have felt threatened by County Sheriff David Clarke’s interest in training his deputies to become Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers as “part of Donald Trump’s executive order,” which is upping deportations and making the citizenship process more difficult (Renee).

Many at the demonstration carried American and Mexican flags, while others carried signs that said, “Immigrants Make America Great” and “We are Workers, Not Criminals” (Spicuzza). Below, a video from NBC documented some speeches and events at the Day Without Latinos Rally in Milwaukee.

Not All Unions Are Business Unions

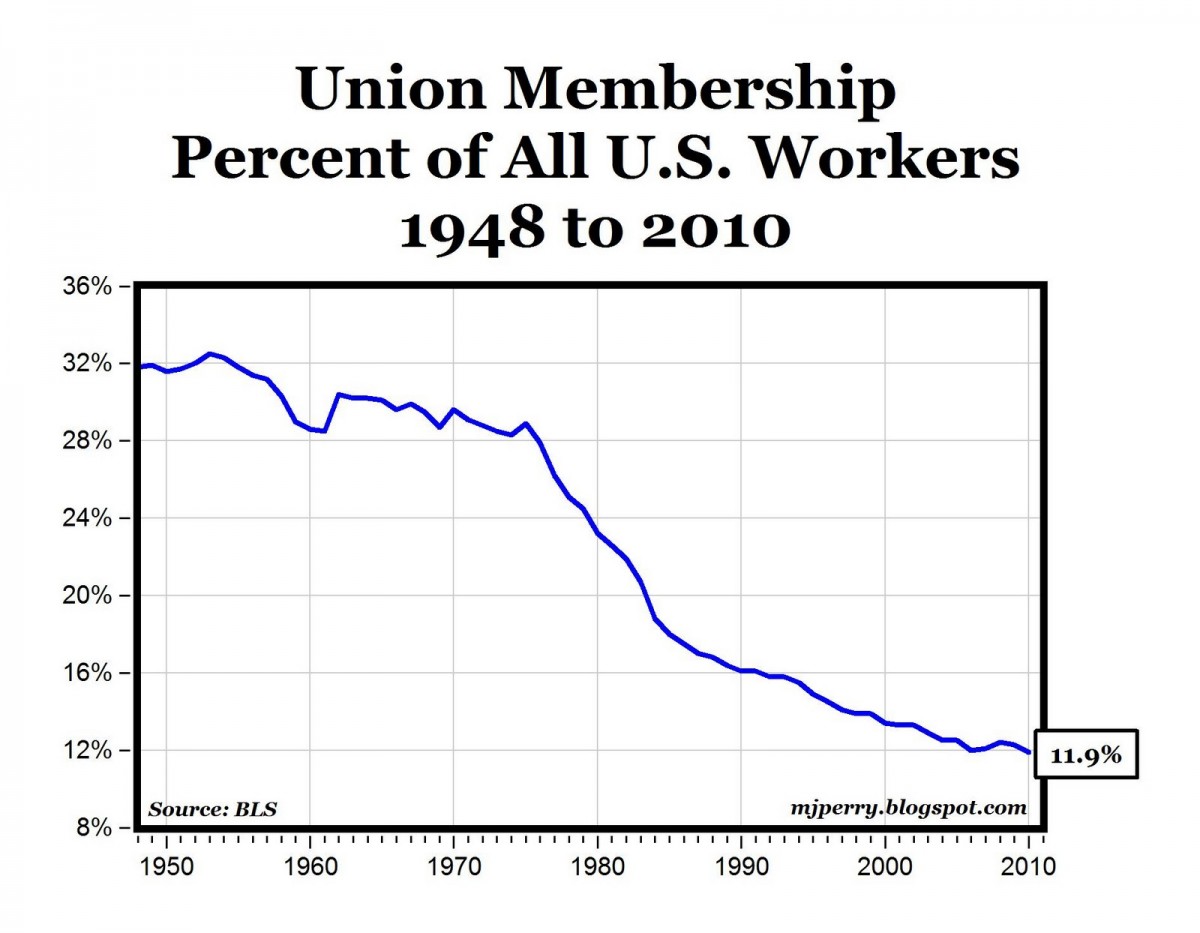

Union membership has been in decline over the past 50 years—in the 1960s union membership was almost 45% of the population in Washington State, and by 2014 it was under 20% (Bui).

Trust in unions, especially business unions, has decreased due to actions these unions have taken. The Los Angeles Federation of Labor worked to gain a minimum wage exemption even though it had campaigned to get minimum wage raised (Redmond). SEIU is investing tens of thousands of dollars into Fight for 15, but is battling the workers they employ for the campaign over a fair wage and a union. “Unions spend millions of dollars yearly… to contact members, educating them about election issues and trying to make sure they vote for union-endorsed candidates,” which makes some wonder if business unions truly care about workers more than politics (Wall Street Journal). Free market capitalists are anti-union and have put effort into discouraging workers from joining unions. Luckily, not all unions are business unions.

Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is an apolitical all-industry union that has existed for over one hundred years. It welcomes everyone but bosses, and particularly mobilizes against capitalism and exploitation. Dues that are paid to the union are used for campaigns and resources for the workers, never to be invested into politicians. Decisions are made in an attempt at anti-authoritarian and non-hierarchical processes; members believe that workers should control their labor and the group fights against violations of workers rights. Membership of the IWW has been steadily increasing the past few months in response to the crisis poor and working class communities have been facing.

The I.W.W and Burgerville

In Portland, Oregon, workers at Burgerville, a fast-food burger shop, began organizing with the IWW to fight for a $5 wage increase and a union. Management was resistant, and the workers received a letter from the CEO Jeff Harvey who says that it could harm the company if they had a union (Culverwell). Workers kept fighting, and eventually were able to negotiate a union contract that is worker-controlled, succeeding through grassroots mobilization and efficient democratic decision making (Katu Staff). Other Burgervilles in the area have joined in the struggle in Oregon and in Washington.

IWW and Incarcerated Workers

The IWW has been working with people in prison, who work for very little or do not even get paid, to illuminate the exploitation of prisoners. Sean Swain, a political prisoner, explains why he thinks prisoners should join the IWW: “Prisons are used for economic purposes. Prisons are a way to lock up the unemployed and to create desperate people to work rotten jobs at low pay. This serves the interests of the rich and powerful and it harms the workers and the poor.” The prison system also targets people of color at much higher rates than white people. To join the IWW is to challenge systemic racism, exploitation, and human rights abuses; prisons are control tools that maintain racial inequalities (Swain).

The Incarcerated Workers Committee (IWOC) was formed in the IWW to directly involve and keep contact with incarcerated workers. IWOC helped facilitate the Prison Strike of September 9, 2016, which was the largest nationwide prison strike in U.S. history (Flowers). Prisoners refused to work, and those outside of prison attended demonstrations and sound demos outside of prisons and detention centers. The IWOC website has a catalogue of union members in prison engaging in many strikes since then.

Prisoners must organize themselves, but the IWW can help provide reading materials, organize rallies, and raise funds to support prisoners.

Conclusion

It is important to highlight the connections between fast food workers, other low- wage earners, people who don’t get paid for their labor, and the movements they are forming to combat the challenges that have and will continue to face them in the era of Trump. Tactics, goals, stories, and experiences of fast food laborers are vital to the Fight for 15 as well as many other labor movements and activities locally, nationally, and around the world.

Voices of prisoners and what they endure daily cannot be left out of the discussion regarding labor. Reproductive labor, which I felt I could not give enough attention with the time and space available, is relatively invisible in labor movements–at least from what media sources have available. Learning about and combating systemic racist violence and economic oppression should be at the forefront of labor politics and movements. Understanding and critically challenging systems of race, class, gender, religion, government, corporations and power and how they function can only be beneficial to workers.

Every movement has its strengths and its weaknesses. In understanding the Fight for 15 intricately—why people join in the struggle, who funds the campaign and why, strengths, weaknesses, and accomplishments of the movement—workers can develop movement-building capabilities while analyzing and utilizing tactics to their best benefit. Recognizing diverse tactics in attempting to fight for workers’ rights is vital to labor movements; questioning intentions of those funding mainstream movements can highlight some of the hypocritical actions of business unions and politicians.

Sources

Agogliati, Michael & White. E. (2017, February 21st). Committee to vote on proposed minimum wage increase. KSLA News 12.

Ariely, D & Norton. (2011, February 3). Building a better America—one wealth quintile at a time. Sage Journals.

Associated Press. (2016, March 9). Small-business owners urge New York gov to scrap plan to raise minimum wage. Fox News.

Aubrey, A. (2016, August 13). Activists gather to push for $15 federal minimum wage. NPR.

Aquinas, A. (2015, January 9). The widening wealth gap in the United States. Activist Post.

Ax, Joseph & Chiarito, R. (2017, February 15). US immigrants skip work, school in Anti-Trump protest. Reuters.

Baertlyn, L., & Layne, N. (2015, April 15). Insight-Union spends big on law-wage campaign, endgame unclear. Reuters.

Baertlein, L., & Lynch, S. (2017, January 12). Fast-food workers protest Trump’s labor secretary nominee. Reuters.

Bernstein, J. (2016, August 10). So far, the Seattle minimum-wage increase is doing what it’s supposed to do. The Washington Post.

Beyerstein, L. (2010, August 19). Why did SEIU give $100,00 to the Republican Governors Association? In These Times.

Bui, Q. (2015, February 23). 50 years of shrinking union membership, in one map. NPR.

Business Live. (2017, February 15). US inflation jumps: What the experts say. The Guardian.

CNN Wire. (2017, February 20). Business owners stand by decision to fire workers who participated in ‘A Day Without Immigrants’ protest. CNN.

Culverwell, W. (2015, April 23). 5 things we learned from Burgerville CEO Jeff Harvey. Portland Business Journal.

Davidson, P. (2016, December 26). What happens to worker pay, benefits under Trump? USA Today.

DeGrave, S. (2017, January 20). Fast-Food Workers Protest Trump, Puzder While Calling for Wage Hike. Texas Observer

Democracy Now! (2017, January 20). Naomi Klein on Trump Election: “This is a Corporate Coup d’État”. Democracy Now.

Durden, T. (2011, June 4). 20 facts about US inequality that everyone should know (with an update on the uber-wealthy and global wealth inequality). Zero Hedge.

Durden, T. (2016, July 14). We’re witnessing a complete breakdown of western values. Zero Hedge.

Editorial Board. (2017, January 2). What Donald Trump doesn’t get about minimum wage. New York Times.

Flowers, S. (2016, September 22). Largest prison strike in U.S. history is happening right now and no one is talking about it. Inquisitr.

Fox News. (2017, January 9). Double Standard? Obama ’09 Cabinet picks slid through; Trump’s face hold-up. Fox News.

Glatz, J. (2017, January 21). Women of color on what’s at stake under President Trump. Fox 61.

Greenhouse, S. (2016, July 24). The rapid success of Fight for $15: this is a trend that cannot be stopped. The Guardian.

Gonzalez, J. (2015, November 10). Gonzales: Fight for 15 strives for economic equality for all. New York Daily News.

The Guardian. (Regularly Updated). The Counted: people killed by police in the US. The Guardian.

Gupta, A. (2013, November 11). Fight for 15 Confidential. In These Times.

Gupta, A. (2016, August 13). Exclusive: Some of SEIU’s “Fight for $15” workers aren’t unionized–and don’t make $15 an hour. Rawstory.

Herbets, A. (2017, February 16). Was the ‘Day Without Immigrants’ protest effective? Fox 5.

Home Care Workers’ Fight for 15. (no date). Home Care Workers’ Fight for 15 wins wage, overtime protections. Fight for 15 Home Care.

Jamieson, D. (2017, January 1). These Hardee’s workers wound up with less than minimum wage under Trump’s Labor Pick. Huffington Post.

Jones, H. (2016, April 14). Fight for 15 now includes child care, home care workers. WNPR.

Kane, L. (2015, June 10). How many hours you’d have to work earning minimum wage to rent an apartment in every state. Business Insider.

katu Staff. (2016). Burgerville workers form union, rally for higher wages. katu 2.

Klein, E. (2013, March 6). This viral video is right: We need to worry about wealth inequality. Washington Post.

Kline, D. B. (2017, January 11). The federal minimum wage hit its peak purchasing power nearly 50 years ago. Business Insider.

Lange, J. (2014, November 25). Why living-wage laws are not enough—and minimum-wage laws aren’t either. The Nation.

Marcetic, B. (2015, October 13). Fight for 15 activists spend Columbus Day rallying against “racist” Donald Trump. In These Times.

Miller, J. (2016, October 25). In 2016 campaign, SEIU seeks to make its mark. The American Prospect.

Moberg, D. (2016, August 4). BREAKING—Fight for $15 organizers tell SEIU: We need $15 and a union. In These Times.

Morris, B. (2006, April 1). May 1. ‘Day Without Latinos’ protest. Politics in the Zeros.

New York Times. (2016, April 28). At McDonald’s: Fat profits but lean wages. The New York Times.

Pratt, D. (2016, August 13). Thousands of protesters at march in Richmond demand $15 minimum wage. Richmond Times Dispatch.

Rainey, C. (2017, February 13). Carl’s Jr. and Hardee’s had to fire 1,200 undocumented workers in 2014. Grub Street.

Recomposition. (2017, January). The potential for a renewed workers movement in an era of dangers. It’s Going Down.

Redmond, S. (2016, August 18). Does SEIU outsourcing deny workers’ union rights? US Chamber of Commerce.

Renee, S. (2017, February 13). ‘Day Without Latinos’: Thousands protest immigration crackdown in Wisconsin. NBC News.

Resnikoff, N. (2016, May 23). Minimum wage and fast-food workers: Now, ‘Fight for $15’ organizers want to join a union, too. International Business Times.

Rifai, R. (2016, November 29). US sees largest protests calling for $15 minimum wage. Al Jazeera.

Rodionova, Z. (2017, February 20). Day Without Immigrants: More than a hundred US employees sacked for taking part in protest. The Independent.

Rosenberg, J. (2014, November 1). Small business divided over minimum wage vote. USA Today.

Rupcich, C. (2016, August 13). Thousands march on Monument for $15 minimum wage. WTVR.

Shirodkar, S. (2015, May 4). Reportage: Minimum wage protests. Sketch Away.

Spicuzza, M. & Nelson, J. (2017, February 13). A Day Without Latinos’ protesters march to Milwaukee County Courthouse, denounce Sheriff Clarke. Journal Sentinel.

Swain, S. (no date). Why should prisoners join the Industrial Workers of the World? IWW Incarcerated Workers Committee.

Taylor, K. (2017, January 10). Trump’s pick for labor secretary runs a fast-food chain where 2 in 3 women report being sexually harassed on the job. Business Insider.

Turna, S. (2017, February 19). Andrew Puzder withdraws nomination for labor secretary. The Tempest.

Wall Street Journal. (2012, July 10). Political spending by unions far exceeds direct donations. Fox News.

Weber, B. (2013, June 24). The reality of who actually works for the minimum wage will shock you. Upworthy.

Zampa, P. (2017, February 8). National right to work legislation introduced to give workers options. KMTV.

Zillman, C. (2015, March 31). Child care works join fast food workers’ fight for $15 an hour. Fortune.