Tori Chapman

The Nisqually Tribe has inhabited the Nisqually River Watershed for thousands of years prior to the arrival of settlers, depending on an intricate food system. Colonization, with its displacement, development, and trauma, then damaged this food system. In consequence, challenges arose to how this community obtained their food. Nisqually activis, Billy Frank Jr. described this right to preserve food as a way of life in his book, Tell the Truth: “Food sovereignty is the right of people to eat healthy traditional foods that are produced sustainably and don’t harm the environment” (Frank, 181). Food sovereignty not only allows bodies to heal, it also helps to preserve traditions, all the while helping the environment. To understand food sovereignty, we must first understand the historical context of colonization, and how other historic and modern pressures have impacted food sovereignty, and deepened resistance and resilience against a commodified food system.

A History of Resistance

The Puget Sound War, 1855-56

The Nisqually Tribe has been a historical center of resistance for access to sacred lands that were also a source of food. According to Charles Wilkinson’s Messages from Frank’s Landing, the U.S. military warred with the Nisqually after the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek, when Chief Leschi refused to move his people to the small reservation designated by Governor Stevens away from the rivers and plains (Wilkinson). In the words of Billy Frank Jr., the conflict happened when “Leschi said, ‘We’re not moving.’ That’s when the war started” (Wilkinson, 14). Chief Leschi, among other leaders, resisted displacement of people and the separation from traditional foods.

According to Nisqually tribal member Grace Ann Byrd, on a panel for the National Conference for Native American Nutrition,

“Our Chief Leschi, knew the value if the Nisqually River and the land and what it meant for the Nisqually- when he and his warriors fought for our treaty rights to hunt, fish, and gather foods and medicines culturally from the mountains to the Salish Sea. He and many others fought for our rights to live alongside the Nisqually River” (Blacketer).

The Right to Fish

While conflict arose, and great injustices were committed against the Nisqually Tribe, the right to feed themselves as an independent people was secured in the 1855-56 Puget Sound War. After much resistance and repression, the reservation was relocated to a larger land mass located by the river and plains. The people fought to stay on their homelands, and this new location allowed access to places where they could continue to fish. The treaty included “a clause securing to the tribes to take fish ‘at all usual and accustomed grounds and situations, … in common with the citizens of the territory’’ (Wilkinson, 12). The 1854 Medicine Creek Treaty thus also secured the right to continue harvesting food even off the reservation.

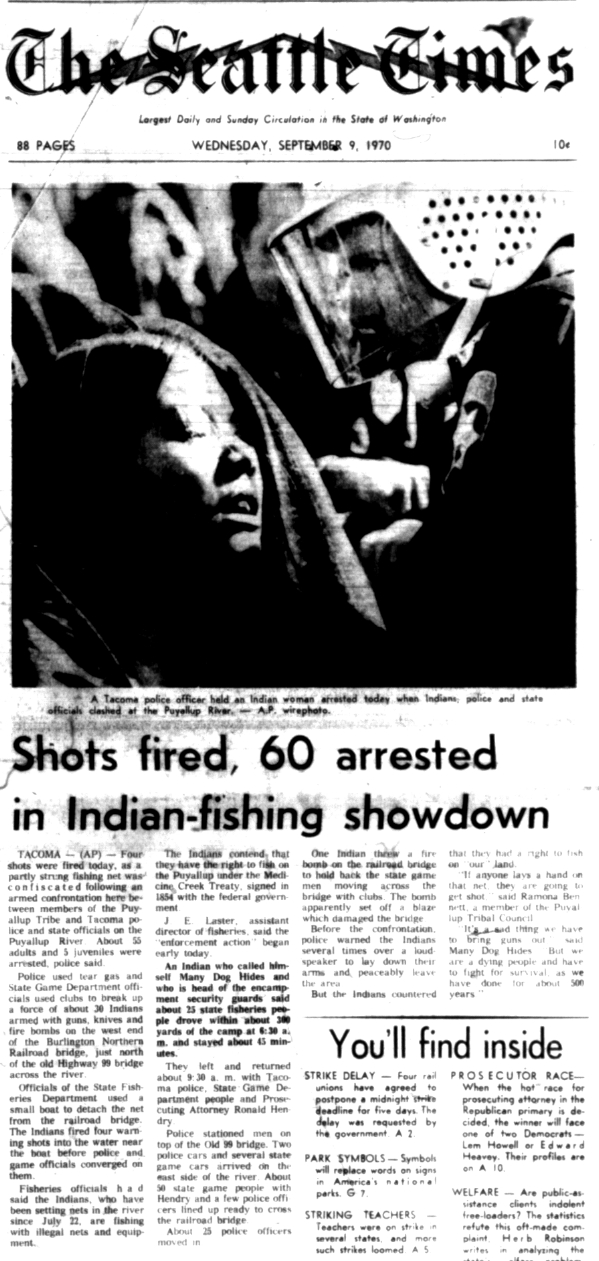

The Second Wave: The Fish Wars 1960s –70s

In the century following the Puget Sound War, conflict over the right to fish arose in what is now known as the Fish Wars during the 1960s and 1970s. This was a period of resistance against the disregard for rights promised by the Treaty of Medicine Creek (Wilkinson). During this time, state conservation policies criminalized Native fishermen who were exercising treaty rights by fishing off the reservation in order to make a living, feed their families, and continue cultural practices. Conflict resulted between groups such as sports fishermen, Native fishermen, and law enforcement. These conflicts drew national attention, and the Nisqually were once again on the frontlines in defense of food sovereignty.

Outcomes

Resistance, in the form of civil disobedience and activism, was successful. These actions eventually lead to the Boldt Decision of 1974 (Wilkinson). Billy Frank Jr., was an influential figure in this movement. His achievements as one of the are seen here in part of his biography provided by the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission:

“Beginning with his first arrest as a teenager in 1945 for ‘illegal’ fishing on his beloved Nisqually River, he became a leader of a civil disobedience movement that insisted on the treaty rights (the right to fish in “usual and accustomed places”) guaranteed to Washington tribes more than a century before. The “fish-ins” and demonstrations Frank helped organize in the 1960s and 1970s, along with accompanying lawsuits, led to the Boldt Decision of 1974, which restored to the federally recognized tribes the legal right to fish as they always had” (NWIFC).

Leading the Way for Resilience

While the Tribal Nations of the Pacific Northwest were blamed for the decrease of natural capital, Billy Frank Jr. and other leaders organized against the real causes of estuary decline and environmental damage. Billy Frank Jr. continued to advocate for not only fishing rights, but for habitat and cultural preservation (Frank). He received numerous awards, including the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism in 1992, and was awarded for his life’s work, being twice recognized by President Obama (Yardley). Among these award, were the Medal of Freedom (Toohey). While Frank acted in resistance, he also led the way for resilience to grow in his life and in the lives of those he left behind.

Impacts of Colonization: Dikes, Dams, and Decline

When settlers came, the land and waters that once had belonged to the Nisqually were dammed, diked, drained, and turned into farmlands. Farming and agriculture arose around the Nisqually River and forests were commodified as lumber (Wilkinson). This damming, diking, and grazing of land on the Nisqually watershed disrupted not only the ecosystem but the Native food system as well. For example, sheep overgrazed the carefully maintained prairies where traditional foods and medicines had been harvested:

“Sheepherders grazed their animals on the Nisqually Prairies. Billy’s [Frank Jr.] dad witnessed the results. The overgrazing took out most of the native carrots, potatoes, and onions. ‘The sheep destroyed all the roots. They left nothing'” (Wilkinson, 89).

A Bigger Threat Than Farms

Throughout its history, the Nisqually Delta has been put in danger of industrial development. The 1982 Weyerhaeuser Export Facility at DuPont Final Environmental Impact Statement, a compiled series of reports and testimonies from the Seattle District Corps of Engineers Department of the Army, details a rich and at times shocking series of events related to the proposed development of the Nisqually Delta. The Delta is a place rich in beauty and biodiversity, that also is vital habitat for many species in Native food systems.

According to these documents, corporate interests interested in converting the Nisqually Delta to industrial use included Weyerhaeuser, the Port of Tacoma, and the City of Seattle, which explored the possibility of turning the Delta into a garbage dump in 1965 (Weyerhaeuser Export Facility at DuPont Final Environmental Impact Statement). As the Fish Wars were waging, collective opposition against the development of the Nisqually Delta was building. While farming damaged the estuary, there were times when alliances were formed between local farmers and the Tribe.

Cooperation in the Nisqually Delta

Cooperative Resistance Against Development

Farmer Ken Braget joined the Nisqually in fiercely opposing the proposed construction of a Weyerhaeuser export docking facility in the otherwise untouched Nisqually Delta. In the 1982 documents and local media, Braget spoke out at public meetings against development of such a port (Weyerhaeuser Export Facility at DuPont Final Environmental Impact Statement). Braget spent his entire life resisting encroachment on the Delta. According to the Seattle Times, Braget even refused to accept payment of a million dollars from the Port of Tacoma in 1970 (Kelleher).

Descendants of settlers who lived on farmland on the Nisqually Delta opposed the corporatization of their properties. Among these farms was the Braget Farm, which was last in ownership of Ken Braget, a fierce advocate for private property rights, with a rather stunning piece of private property on the east bank of the Nisqually River; which the Seattle Times described as, “410 acres of Nisqually riverfront pasture, salt marsh and forested uplands. Braget’s family has been on this farm since the turn of the century” (Kelleher).

Resilience in Friendship

As he approached old age, Braget ensured that his land would not fall into the wrong hands. In 1996, the Seattle Times reported that Braget had “negotiated a deal with the Nisqually Tribe for a $4.25 million purchase of his farm,” in exchange that he be allowed to live there until he died (Kelleher).

Ken Braget, lived the rest of his days on his land, and passed away in 2006, ten years after he promised the land to the Nisqually (Nisqually Land Trust 2006). His act of preservation was not forgotten by the Nisqually Tribe. Billy Frank Jr., thanked his friend Ken, in a beautiful tribute written in the winter of 2006:

“A cattle rancher and a neighbor of mine in the Nisqually watershed, Kenny Braget lived the life of a steward. He proved the belief that actions speak louder than words. No one’s actions spoke louder than Kenny’s. My lifelong friend passed away this summer, but his legacy will live on. Kenny was a champion of the Nisqually River. He took a bold stand against converting the estuary into an open water port. Without him, the mouth of the Nisqually might be like many rivers in the Puget Sound: saturated with poisons, bloated with urban sprawl, and devoid of fish, animals and birds. Decades ago, he enthusiastically came to the table as citizens, governments and businesses from the mouth of the Nisqually to Mount Rainier decided to work together to preserve natural habitat along our river. With Kenny’s help we established the Nisqually River Task Force and, with his ongoing support, it grew into an effort that has inspired watershed management programs near and far. In the winter of his life, Kenny could have subdivided his 420 acres, permitted development to creep in, and lived out his years a wealthy man. But Kenny was interested in other kinds of riches. He didn’t value his property by what it was worth in dollars. Instead he sold his property to the Nisqually Tribe, knowing that we would manage it in a way to protect and enhance the quality of all life in the delta. He knew we would tear down the dikes that his family built to protect their fields from the salt water. Today, those fields are a nesting place for birds, an incubator for young salmon, and a refuge for returning adult salmon. Despite the pressures of growth that Kenny felt and fought much of his life, the estuary is still a place where you can smell the tide that supports life throughout the watershed. That estuary is Kenny’s memorial. Several-hundred people braved near-freezing temperatures to dedicate the newly created Braget Marsh and to say goodbye to Kenny. Tribal members rejoiced with dancing, drumming and singing. The tide moved in slowly. Only this time, the water reclaimed the land where Kenny’s cattle once roamed. It glided onto the land that, until that day, had been kept dry by 9,000 feet of dikes. One hundred acres of the old Braget farm were reclaimed by the waters of Puget Sound, soon to be occupied by a variety of fish, waterfowl and thousands of other native species. The estuary is coming to life again, right in front of our eyes, and I think Kenny is smiling” (Frank,110).

From Resistance to Resilience

Why the Braget Farm is Important

In closing a chapter of resistance, and opening a new one grounded in resilience, it must be noted that in the past, the fight against industrial development impacted food sovereignty for the Nisqually Tribe. In the case of Ken Braget’s final wishes for his home, the land he left to the Tribe has returned places of great importance. With this land the Nisqually has both committed to restoration in the Delta, as well as built a community garden.

Impacts of Farming

When colonization happens, indigenous food systems are usually heavily impacted. The large scale introduction of people, logging, agriculture, and farming in the Nisqually Valley took a toll on the health of the Delta (Wilkinson). Cattle trampled native plants and compressed the soil, sheep and other livestock overgrazed, and dikes dried wetlands (Wilkinson). Today ground water pollution from farm wastes and runoff are a major health concern:

“Fecal coliform levels sometimes exceed regulatory limits. Because of this, the Washington Department of Health has declared that the shoreline off the mouth of the Nisqually must be closed to commercial shellfish harvesting for five days following any rainfall of one half inch or more. Remember that Billy Frank’s generation, and the Nisqually people for hundreds of generations before him. once drank out of this river” (Wilkinson, 89).

The degradation of watershed health also damaged the Native food system, for instance the construction of dikes on the Delta drastically decreased the size of estuary habitat such as marshlands, which are crucial to supporting salmon populations. In order to exercise treaty rights, there has to be something left to harvest in the first place.

Healing the Land

The Braget Farm dikes were removed in efforts to restore the Estuary and salmon habitats beginning in 2006 (Dodge). Though this was not the first time that estuary protection has occurred, a series of purchases have led to restoration on the Nisqually Delta. The land on the west bank of the river, the Brown Farm, was included in the purchases of 1974 that created the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). In 2016 the Nisqually Wildlife Refuge was renamed the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge (Nagel).

The Restoration of the Nisqually Estuary that was once farmland. (Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ducks Unlimited, Youtube).

Cooperation in Restoration

Joint efforts in the name of river restoration have occurred between partnerships of Native and non-Native communities, leading to partnerships and the founding of numerous organizations with the common intent of protecting the watershed, such as the Nisqually Land Trust, which now “has preserved 1,700 acres of critical habitat in the river basin” (Dodge).

In 2016, the Seattle Times also reported that within the five years since massive removal of the remaining dikes located around the opening of the Delta, there have already been improvements. Biologists reported higher than usual densities of juvenile salmon per square mile (Nunnally).

Current or Potential Threats

In a closing note on restoration, I must also point out the potential threats. On a down note, the health of this estuary greatly depends on conditions such as climate, pollution, and deforestation. If these habitats are swallowed by a rising and/or acidic sea they might not be as habitable for juvenile salmon or other key parts of estuary ecology (Nunnally).

Rising sea levels may likely threaten homes that are too close to sea level (Basne). In addition to these concerns about climate change, there are also concerns over possible contamination via fossil fuels. (Weyerhaeuser Export Facility at DuPont Final Environmental Impact Statement).

Though pipelines do not go through the reservation, they do cross the river and its tributaries (ArcGIS). In the 1990s an error led to the explosion of the same company’s pipeline in Bellingham, Washington. This explosion killed wildlife as well as two young children and a young adult (Millage).

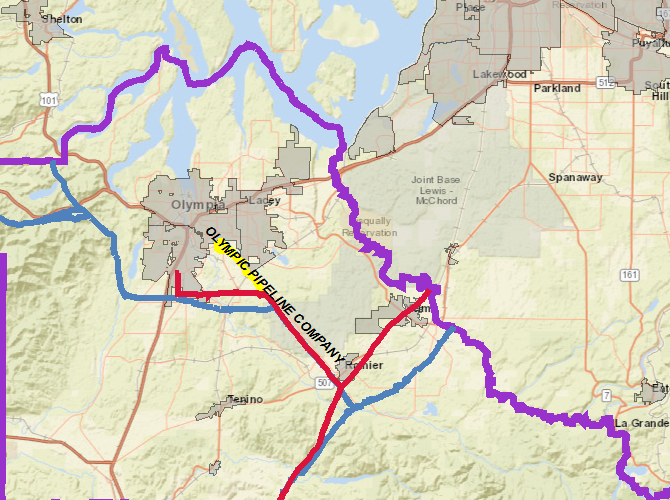

Pipelines in Thurston County

The Nisqually River watershed is located in both Pierce and Thurston counties. The river divides these two counties. The following map shows where pipelines and some railroads are in Thurston County (ArcGIS).

What Restoration Means for Food Sovereignty

There is a proverb among many Coast Salish tribes that “when the tide is out, the table is set.” The people who inhabited these areas, mostly in western British Columbia and Washington State, have held salmon sacred– both for its nutritional and cultural significance. Salmon are a central part of the traditional diet. In order to preserve fish runs, there had to be a healthy river. The delicate ecosystem found in the Nisqually Delta is vital for salmon population restoration, as young salmon thrive in these marshy habitats.

The Nisqually Delta is vital to a healthy ecosystem as well as the bodies and cultures of the Nisqually Tribe. The preservation of an ecosystem that can support fish and wildlife is crucial to the ability to both continue practicing food sovereignty and to exercise treaty rights upheld by the Boldt Decision. According to the Olympian,“The Tribe recognized that their ability to harvest their 50 percent share of the number of harvestable fish coming back was dependent on the availability of the habitat that the fish depend on” (Nunnally). Food sovereignty is not just about food, but preserving the right to gather, hunt, or grow healthy foods, and stewardship of the earth.

As Billy Frank Jr. put it in Tell the Truth, “If we lose our ability to hunt, we lose an important source of traditional food, and we can’t afford to do that. Indian people evolved eating traditional foods like elk, salmon, clams and berries. These are the foods that are best for our bodies.” Frank maintained that we “must continue to be good natural resources managers. Our treaties recognize that food is at the center of our cultures” (Frank, 186). In this case, the preservation of an ecosystem is tied to the preservation of cultures.

The Importance of Food Sovereignty

According to the Northwest Indian College, the historical and on-going displacement of Native Americans negatively impacts the health of individuals generations after removal and diets supplemented by government aid are void of nutrients found in traditional diets:

“Tribal communities still rely heavily on government commodities and state and federal food programs to feed their people. While food that is provided has improved over the decades, it is fresh produce, good quality proteins and healthy fats that were the foundation to a healthy traditional diet are not as available in these food programs. Additionally, state and federal food programs often mandate what types of foods must be served, even if they are not culturally appropriate. This is where the importance of food sovereignty is evident” (Northwest Indian College).

When colonization happens, indigenous food systems are usually heavily impacted. The Western food systems are not as nutritious; just as these lacked vitamins they also lacked cultural context. To combat these historic injustices, the Nisqually Tribe invested in food sovereignty programs. While restoration is important to food sovereignty; the garden also plays a central role.

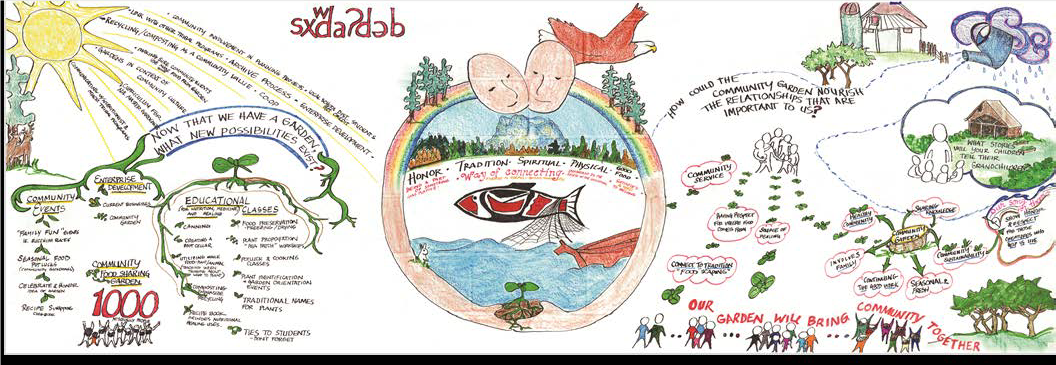

The Nisqually Community Garden

The Nisqually Community Garden and market (Source: Olyphoto, YouTube).

The Fate of the Braget Farm

The Braget Farm location, was both used by the tribe to restore some of the surrounding ecosystems, but to also to build a community garden. According to garden production supervisor Carlin Briner,

“Nisqually Community Garden was started in its current location in 2009 to support healthy lifestyle development and contribute to tribal food sovereignty and the healing of historical traumas” (2015 Farm Walk Program).

Traditions such as the value of elders are upheld as the garden gives the elders access to nutritious foods; the community garden is an example of community-based and intergenerational action.

Why Gardens Matter

This was not the first tribal garden. As reported by field technician Grace Ann Byrd during the annual Conference on Native American Nutrition, the Nisqually Tribe had started a community garden back in the 1980s, but parking lot construction on the reservation ousted the garden (Blacketer et al). The gardens held deep meaning, Byrd explained, as they strengthen community and was a way to give back to the elders who had worked to provide for her generation on farms or during the Fish Wars (Blacketer et al). Since moving to a new location, the community garden has indeed become a tool for community building, and has allowed for people such as Byrd to give back to their elders.

Though the Nisqually community has multiple gardens, including those located at the youth, elder, and Head Start centers, the largest one is located on the Braget Farm site. According to Briner, berries, produce, fruits, traditional plants and medicines are mostly grown (2015 Farm Walk Program). The Braget Farm site also features trees are over a hundred years old, and were planted by the Braget Family (Blacketer et al).

This community garden is highly successful and sustainable. According to the Olympian, not only does the garden create job training opportunities, but in 2013 over 5,000 lbs. of produce were distributed from the garden to tribal members. (Pemberton).

The aim of the community garden, is to work towards “tribal self-sufficiency and overall community, family, and individual health.” (Nisqually Indian Tribe). These goals are achieved according to the Tribe through,

“encouraging the active practice of traditional ways of healthy living & eating. The Garden contributes to real improvements in physical, spiritual, mental, and emotional health. We grow and distribute food, medicinal plants, and body care products to Tribal members and community members. We also coordinate classes and workshops so that people can build skills in growing, harvesting, and preparing their own foods and medicines.“ (Nisqually Indian Tribe).

The Nisqually Tribe also provides a gardening blog on best practices, a class and delivery schedule, and a recipe search engine for tribal members to learn how to cook what they get from the garden stand, including how to prepare traditional foods. (Nisqually Indian Tribe). The garden also works with other food cooperatives such as Garden Raised Bounty, based in Olympia (2015 Farm Walk).

The Braget Farm site is now home to a place of healing, growing, community, hard work, and fun. In an interview of Grace Ann Byrd, she cheerfully provided some of her highlights about what she liked most about the gardens, including harvest parties, “watching the little kids pick their own carrots, being able to take to take food to our elder center, but also working with our co-workers and seeing them grow as well…” (Baca).

The Nisqually Community Garden promotes community growth and nutrition. It is a stand against limited access to healthy foods and it strengthens ties to the community and to culturally significant places and practices. Food sovereignty ties into restoration of the land and culture of the inhabitants, healthy bodies, and collective healing as a community and as a people.

Conclusion

The path towards food sovereignty in a post-settler world was first, one of resistance as in the Puget Sound and the later Fish Wars. A time of cooperation and resilience followed through the restoration of the Estuary and in the construction of a community garden. Through these acts of resistance and resilience, the Nisqually people have worked to preserve their culture, land, and food sovereignty. In closing I believe that existing programs are not quite done yet, but what I am certain of is that the resilience of the Nisqually people is as strong is as it is deep, and food sovereignty programs will continue to grow.

Special Thanks

I would like to thank the Nisqually Tribe for allowing me to use their media sources in this page, as well as congratulate them on the Community Garden. I also would like to thank the Yelm History Project and The Evergreen State College for their spectacular maps.

I spent many weeks on research, and I have some critiques about my sources. I feel as if I did not have as much access to older documents as I would have liked, and that I relied more on these as well as books, neither of which may be readily accessible to those who are viewing this page. I also feel as if my sources have more listed, so that people can go an dig as they please and make their own connections. As a local to the area, some of the events that I remembered and wanted to write about, were not covered in local media. Had I been more prepared, I would have liked to do some interviews.

Sources

2015 Farm Walk Program. (2015). FW_2015_Nisqually. Tilthproducers.org.

ArcGIS – Pipeline Thurston County. (n.d.). arcGIS.com

Baca, A. (2014). Nisqually Tribal Farm in Washington State. YouTube.

Basne, T. (2012, March 16). Study: 17,500 Northwest Homes In Harm’s Way From Rising Seas. National Public Radio

Blacketer, J., Byrd, G. A., and Krenn, C., Annual Conference on Native American Nutrition. (2016 Nov, 23). Nisqually Community Garden. YouTube.

Capalbo, S. (n.d.) Northwest | National Climate Assessment. globalchange.gov

Chrisman, G. (2008). The Fish-in Protests at Franks Landing. University of Washington. Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. civilrights.washington.edu.

Dodge, J. (2016, October 8). Nisqually project helps reverse decades of decline The Olympian.

Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014). An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press.

Frank Jr., B., (2015). Tell the Truth. Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission. Northwest Treaty Tribes

Hobbs, A. (2017, Jan 11). Olympia’s McAllister Springs site to return to Nisqually Tribe. The Olympian.

Hoover, E. (2014, October 21). From Garden Warriors to Good Seeds: Indigenizing the Local Food Movement. Nisqually Tribe Community Garden, Dupont WA. Gardenwarriorsgoodseeds.com

Indigenous Farming Project (2014, September 5). Nisqually Community Garden – Dupont, WA. Nativefarms.org

Kalliber, K., Pemberton, L. (2014 July, 17). Nisqually Tribe’s garden program cultivates tradition, community | Tulalip News

Kelleher, R. (1996, March 31). Shifting Tides –– Newcomers Awaken The Sleepy Nisqually Delta. Seattle Times

Millage, K. (2009, June 7). Timeline of Bellingham Pipeline Explosion. The Bellingham Herald

Morgan. (2017, January 25). Tell Our Story, Pt. 7: Nisqually Indian Tribe protects biodiversity – Nisqually River Council. Nisquallyriver.org

Nagel, M. (2016, July 18). Secretary Jewell to Celebrate Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge and the New Medicine Creek Treaty National Memorial in Washington State. FWS.gov

Nisqually Indian Tribe. (n.d.). Community Garden Program. Nisqually-nsn.gov

Nisqually Indian Tribe (2015). 2015 Elders, Head Start, & Youth Gardens. (2015). Nisqually-nsn.gov

Nisqually Indian Tribe. (2011). Master Plan 2011-2012. Nisqually-nsn.gov

Nisqually Land Trust. (2006). Land Trust Completes Largest Deals in History. Nisquallylandtrust.org

Nisqually Land Trust. (n.d.) Welcome to the Nisqually Land Trust. Nisquallylandtrust.org

Nisqually Treaty tribes. (2016). Nisqually Tribe salmon carcass tossing community event. YouTube

Northwest Area Committee. (2015). Nisqually River Geographic Response Plan. Ecy.wa.gov

Northwest Indian College. (n.d.). Traditional Plants and Foods. Nwic.edu

Northwest Indian College. Traditional Plants and Foods Program. (n.d.). Tribal Gardens. nwicplantsandfoods.com

Northwest Indian College. (n.d) Tribal Community Food Sovereignty. nwicplantsandfoods.com

Nunnally, D. (2016 Sept., 2). Nisqually River Delta Dike Removals Showing Results After 5 Years. The Olympian

NWIFC. (2017). The Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr. Billyfrankjr.org

Olyphoto. (2014). Nisqually Tribe Community Market and Farm Stand. YouTube

Pemberton, L. (2016, July 16). Nisqually Tribe’s garden program cultivates tradition, community. The Olympian.

Smith, M. (1940). Puyallup-Nisqually. Columbia University Press. Nisqually Villages. Yelm History Project. Yelmhistoryproject.com

The Seattle Times. (2011, August 24). Nisqually River to flow freely after dike removal. The Seattle Times

ThurstonTalk. (2015, May 13). Congressman Denny Heck Introduces the Billy Frank Jr. Tell Your Story Act. Thurstontalk.com

Toohey, G. (2015, November 25). Obama awards medal of freedom to Billy Frank Jr. Bellingham Herald

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (2011). Rivers and Tides: Restoring the Nisqually Estuary. YouTube

Washington Salmon Recovery Progress by Region. State of Salmon. (n.d.). Stateofsalmon.wa.gov

WDFW. (2012). Estuary and Salmon Restoration Program Advancing Nearshore Protection and Restoration 2012 Program Report. wdfw.wa.gov

Weyerhaeuser Export Facility at DuPont Final Environmental Impact Statement. (1982) (Vol. iii). Seattle, WA: Seattle District Corps of Engineers Department of the Army.

Wilkinson, C. (2000). Messages from Frank’s Landing. University of Washington Press.

Yardley, W. (2014, May 9). Billy Frank Jr., 83, Defiant Fighter for Native Fishing Rights. The New York Times.