Christina Cravens

Iran’s primary commodity has long been oil. According to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, Iran is ranked fourth in the world in the size of oil reserves. Its export economy functions around the extraction and production of petroleum. To understand the internal political movements and struggles of Persia and Iran against foreign domination, one cannot separate its history from oil.

History of Iranian Oil and British Influence

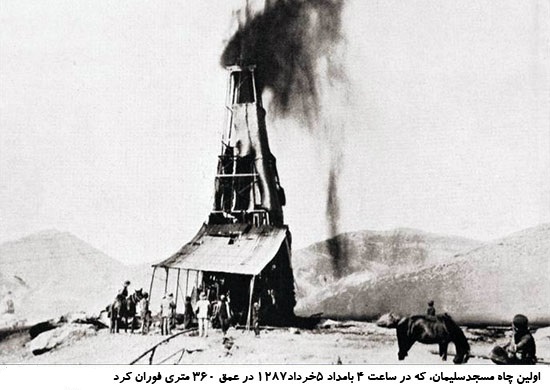

In 1901, William Knox D’Arcy, described as “a millionaire London socialite,” whose fortune came from a goldmine in Australia (Voltz), signed an agreement with the Shah of Persia to be the exclusive prospector of oil in a vast sector of the country. In return William Knox D’Arcy promised £20,000, equal shares in the company, and 16% of future profits. After seven years and millions of pounds of searching for oil, D’Arcy and their partners were close to closing down their venture in Iran. As a last stroke of luck, George Reynolds, partners with D’Arcy, discovered the greatest oil field found to this date on May 26, 1908 on the desert island of Abadan, in the southwestern region of Arabistan (Khuzestan). British leaders were quick to jump on obtaining such a promising source of oil. “In the autumn of 1908 they arranged for a group of investors to organize a new corporation, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, to absorb the D’Arcy concession and take control of oil exploration and development in Iran… the British government spent £2 million to buy 51 percent of the company. From that moment on, the interests of Britain and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company became one and inseparable” (Kinzer).

World War I ended with an Allied victory, in no small part to a vast supply of profitable oil. The Persian population was growing to question their 16 percent royalties, as inequalities between the British and Persians were widening. Reza Shah and his ministers attempted to renegotiate with the British, but talks went nowhere for four years. The Depression of the 1930s significantly impacted the economy of Persia, which was renamed Iran in 1935. Reza Shah was fed up with the British giving him the cold shoulder, and cancelled the D’Arcy concession (Voltz).

The British were appalled and appealed to the League of Nations. The British claimed that by cancelling the D’Arcy Concessions, Iran was preventing them from obtaining what was considered legally theirs. Iran fired back, claiming the British had been undercutting its 16 percent royalties, considering they were the only ones who had access to the financial documents. Shortly thereafter, they came to a compromise. The area covered by the D’Arcy concession was significantly reduced, Iran would receive a minimum of £975,000 annually, and Britain would improve working conditions at the refineries. Under these new terms, the contract was extended for another 32 years until 1961, and changed the name from Anglo-Persian Oil Company to Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (Mina).

Life Under Reza Shah, 1925-1941

Reza Shah was elected as the Prime Minister of Iran in 1925, after the fall of the Qajar Empire. “Within four years he had established himself as the most powerful person in the country by suppressing rebellions and establishing order” (Pahlavi Dynasty). He implemented policies that produced dramatic infrastructural changes, through centralizing government power, proving to be largely successful. Nevertheless, Reza Shah was a dictator who benefited from Britain’s influence. And although he was not entirely corrupt, he always attempted to rig the political game to always be in his favor. He silenced dissent, rigged elections, financially swayed other political players, and limited the power of other institutions in order to increase his power over them. He was determined to govern as he pleased. But his power to reign was limited by various foreign influences during World War II (1939-1945). During the 1940s Iran was split into sectors, with a Soviet zone in the North, a British zone in the South, and only the mid-section governed by Iran, closely monitored by foreign powers. The Allied forces utilized Iran for the war cause. “As long as the war was on and Iran was under military occupation, dissent was muted. Slowly, however, political life resumed” (Kinzer).

Iranian Working Class

The Iranian population felt as if the Shah had made too much of a compromise when negotiating with London. Conditions had not changed significantly enough for the people. The increase in annual payments only benefited the government and the working conditions had not changed. Given Soviet influence, many workers began to embrace Communism. Reza Shah attempted to silence them with imprisonment, but by doing so inadvertently created the space for people to organize while they were behind bars to form the first real political party called Tudeh (Behrooz).

In 1941, Reza Shah abdicated, and then replaced by his son. Labor movements, the Majlis (the Parliament), and social organizations came back to life with the departure of Reza Shah. Protests and demonstrations grew more frequent as there was more room for dissent against foreign influence. “Discontent over the company’s privileged position grew steadily during the war years as the amount of oil it extracted rose from six and a half million tons in 1941 to sixteen and a half million tons in 1945” (Kinzer).

Wages were almost nonexistent, workers were crammed into slums, and they barely had access to basic necessities. Bloody strikes and violent riots were happening, fighting to hold the British accountable to observe the Iranian labor laws. The demonstrations created enough of a problem that London could no longer ignore their demands.

Negotiations

As a reaction to the strikes, Britain drafted the Supplemental Agreement. It stated that £4 million was guaranteed in annual royalties, a further reduction of the area that was being extracted from, and a promise to train Iranians for more administrative positions in the company. This agreement still would prevent any ability for the Iranians to check the financial records of the company. Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi demanded the cabinet to approve the Supplemental Agreement, but he did not have enough power to sway the Majlis (Parliament) who also had to approve it. The Majlis representatives were elected by the people, and accurately represented their desires more than other branches of government. Reelection was coming up and Mohammad Reza Shah was trying to cheat the elections to work in his favor, which was a major mistake. A nationalist leader, Mohammad Mossadegh, organized people to demonstrate outside the palace. The Iranian population was charged up and demanding representation and a fair election. The United States had recently made an agreement with Saudi Arabia to equally split the profits of Saudi oil and Iran saw this as a possibility for itself.

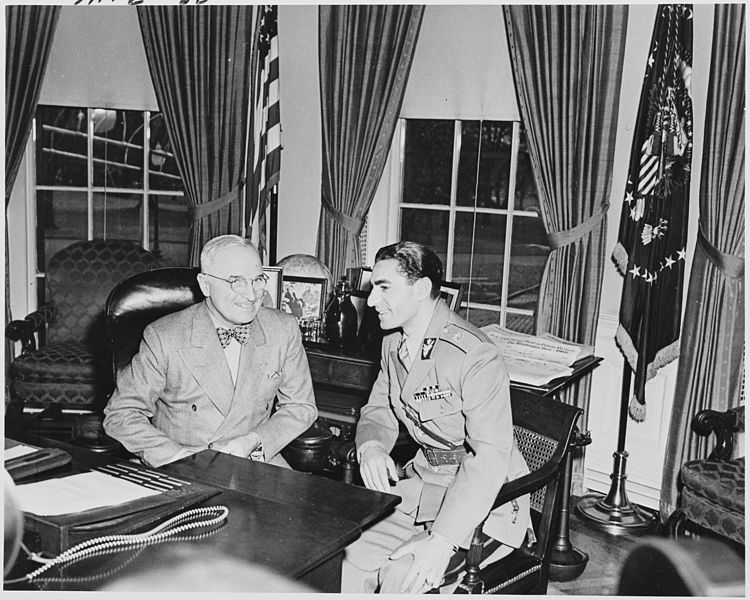

During all this mayhem, the Shah made a visit to the United States. President Truman was concerned with the risk of Soviet influence and the Shah was in desperate need for support. President Truman believed that only social reform would work, but Mohammad Reza Shah was set on furthering Iran’s military capabilities. (Wiley 1949). Although they were at a standstill in discussing future discourse, the people back at home were fervently organizing.

Time for Political Change

Leaders who were demonstrating for a fair election, gathered together to create the National Front. The National Front was a coalition of various political parties, unions, social organizations, and groups that were devoted to democracy, anti-imperialism, and bringing an end to foreign influence in Iran. “Mossadegh and six other founders of the National Front were elected to the Majlis in the new election they had forced the Shah to call” (Kinzer).

The British were appalled by how out-of-hand the situation had gotten, and strongly advised the Shah to get rid of Prime Minister Mansur and replace him with General Razmara, who was a politician in the pockets of foreign influence. This further energized Iranians’ desire to bring an end to foreign influence. British and U.S. ambassadors frequently visited to try and settle the situation, which only charged the population more.

Even the religious leaders were joining the movement, such as Ayatollah Abolqasem Kashani. It became an Islamic duty to rid the land of the colonial yoke. Islamic scholars were central to the anti-imperialist movement. Although their reasons were slightly different than the nationalists, the joined together to create mass public support for self-determination and sovereignty (Sreberny and Torfeh).

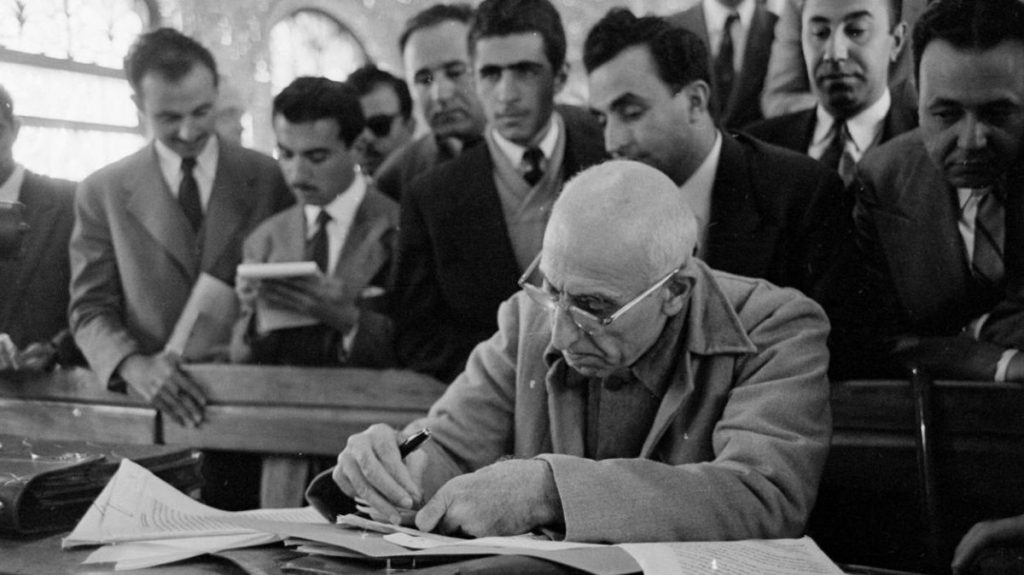

By 1951, Mossadegh suggested Iran should nationalize the oil company. Although most of the National Front and Majlis were not ready for such a radical idea, it became a bulb in bloom. It was becoming clear that negotiations will the oil company and the British government were not achieving anything. It would be an agreement on paper, with no accountability, and for as long as the British had a significant hand in the economy and political system, Iran would not have to ability of self-determination. On March 15, 1951, the Majlis held a vote for the nationalization of the oil, which won unanimously.

The Prime Minister of the time, Hussein Ala, stepped down realizing how little power he had over such a polarized political period. Britain responding by strongly advising the Shah to nominate Sayyed Zia and lower the wages of oil workers even further. When it came time for the Majlis to elect a new Prime Minister, Mossadegh won a considerable victory.

Iranian Oil and U.S. Influence

During the Cold War, Iran was in conflict with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and Great Britain, and the United States was in conflict with the Soviet Union. The United States was allied with Great Britain in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The Cold War exemplified the strength and capabilities of enemies, but also demonstrated the importance of allies. The United States had made a deal with Saudi Arabia for a 50-50 split of oil profits, thinking it was best to be a positive example and a supportive influence rather than exert military force. To exert military force might push nations to seek support from the Soviets. Both London and Washington sought to defeat the Soviets, but with different tactics. Britain felt that NATO would lose the war if they did not have unimpeded access to oil, but the U.S. thought Iran was susceptible to Soviet influence if provoked too much.

President Truman pushed Britain to negotiate with Iran. The British were flexible on profits, but not on the matters of control. Britain’s time to negotiate had come and gone. On May 1, 1951, a law was signed that revoked the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s rights in Iran and replaced it with the National Iranian Oil Company.

Britain was in a fury and began to strategize military action. London refused to back down, thinking that if it made compromises now other colonized nations would start similar uprisings. The United States was frustrated with Britain and tried to disassociate from it, believing that Britain was failing to recognize national aspirations and treating Iran as a colonial pawn rather than an ally. President Truman issued a statement that the United States was in full support of Iran’s aspirations, but Mossadegh must be strategic about their discourse (Truman).

“Truman now saw greater peril than ever. To him, the question of who would control Iranian oil was only secondary. He was more worried that the argument between the United States and Britain over how to deal with Mossadegh might spiral out of control and split the Atlantic alliance. Determined to make a last effort at compromise, he wrote to Mossadegh suggesting direct American mediation” (Kinzer).

Britain’s Reaction

Britain responded to the oil nationalization law, by building up its military presence off the shores of Iran. It had given up on persuading Mossadegh and saw forceful action as its only discourse. It imposed economic sanctions that devastated the economy, closed down the Abadan refinery, sent all the employees home, and prevented any tankers from bringing oil to the market.

Mossadegh Standing Strong

After Mossadegh nationalized the oil industry, the people took over the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s former offices looking for financial records. Most records were destroyed, except in the Tehran office. There was evidence Britain had interfered with Iran’s political processes to work in its favor. Because Britain had undermined the political system’s functions with economic sanctions, Iran was facing extreme economic turmoil. It was prevented from exporting a drop of oil without Britain reporting to the United Nations that it must be returned because it was stolen property.

None of this prevented Mossadegh from standing strong. To London this was about controlling a hot commodity in the international market, to Mossadegh it was a matter of liberation and self-determination. “Such a confrontation had both material and symbolic value; it was a declaration of Iranian sovereignty and economic independence, and it aimed at actual control over the material resources that were essential to that sovereignty and independence” (Humphreys). Mossadegh was willing to compensate the British, supply them with domestic needs and welcome their citizens into the country, as long as it did not interfere with national sovereignty. This attitude changed when he heard that Britain, unwilling to budge, was tired of running into a brick wall and was beginning to strategize his removal from office. On September 6, 1951, Mossadegh threatened to expel British citizens from Iran.

Reaching a Boiling Point

Britain was not making any progress. Even though it enforced an unwritten rule that prevented most countries and companies from purchasing Iranian oil, which created devastating effects, Iran expected and endured the blow for the struggle for sovereignty. Britain took the case to the World Court, where it faced an embarrassing loss. London concluded that in order to undermine Mohammad Mossadegh in a more successful way, Britain was going to need support from the United States. President Truman stood firmly on the belief that Britain should not, under any circumstances, create an armed conflict in Iran. Mossadegh was a man of democracy and self-determination of his peoples. He had successfully linked their struggle that that of the United States struggle for independence from Britain in the 18th century. There were many parallels and Truman was determined to find a diplomatic solution, although some in the U.S. government tried to label Mossadegh as pro-Communist.

In 1951, British Prime Minister Attlee’s Labour government was replaced by the Conservatives, led by Winston Churchill. Former Prime Minister Attlee had been trying to settle the dispute between the former Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and Iran through any method except force. But with the change in government came a change in policy. London’s tactics toughened and were set on deposing Prime Minister Mossadegh.

By each day, Iran was becoming more unstable. For a brief period, Prime Minister Mossadegh had resigned. Although this was not the primary reason why, it was a successful measure of whether the people were still willing to support him even in the increasingly turbulent times. Ahmad Qavam, who was selected by Britain, replaced Mossadegh but only for four short days. The people and even the Shah called upon Mossadegh to return (Memarsadehgi).

Britain had realized that with such mass public support for Mossadegh, it was going to need a strategy that created enough chaos to be able to unroot his influence over the nation. London began laying the foundations for a coup by further funding political actors to help bring about political change, and enlisted General Fazlollah Zahedi be the man to replace the Prime Minister. Mossadegh caught on to the rumors that the coup was imminent and as a reaction broke all diplomatic relations with Britain on October 16th, meaning all British officials were forced to leave by the end of the month. It was ever more clear that the British would need the United States’ help.

The 1952 Presidential elections brought President Eisenhower to office. Much of his campaign rested on an anti-Communist platform. British ambassadors catered to this and swayed Eisenhower to believing, “the longer Mossadegh remained in power, the likelier it was that Iran would fall to communism” (Kinzer). British forces had been conducting covert actions against Mossadegh over the past several months, some of which included propaganda and funding rabble-rousers. President Eisenhower was never intimately involved with the plot against Mossadegh, but given the worsening political climate he funded and approve the CIA’s efforts to work with Britain on such a mission after being convinced it was the best course of action. (Wilber, I)

The Coup

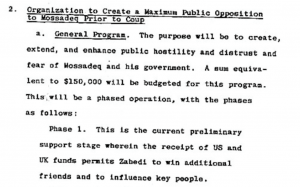

The coup against Mossadegh was orchestrated by only a handful of people from the British Secret Intelligence Service and U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (including Kermit Roosevelt Jr.), along with General Fazlollah Zahedi, the Rashidian brothers, and others that they had recruited along the way. Two primary intelligence officers formulated the strategies to create the perfect environment for the coup d’état. Donald Wilber and Norman Darbyshire, one American and one British, worked closely together to generate the following tactics to remove Mossadegh from power:

- Manipulate public opinion to be against Mossadegh. With a budget of $150,000, they sought to create and enhance hostility, distrust and fear of him and his government by recruiting agents to generate such feelings. They attempted to paint Mossadegh as corrupt, power-hungry, Islamophobic, and a Communist.

- Thugs were to be paid to stage attacks against Muslim leaders and prominent figures that would be reported as actions ordered by Mossadegh.

- General Zahedi was to bribe as many officers and soldiers to help carry out whatever actions necessary to help their cause.

- Money was to continue fund agents of the Majlis to act against Mossadegh and support the Shah and General Zahedi.

- Thousands of Iranians were paid to be demonstrators to create a massive anti-government rally the day of the coup.

(Wilber, IV & V)

The efforts to remove the Prime Minister had to be successful, otherwise the United States’ reputation with Iran would be ruined, and in turn Iran would seek out an alliance with the Soviets.

On August 15th, 1953, they attempted the coup but quickly failed. Prime Minister Mossadegh was under the impression that the Shah was acting on behalf of Britain and sent him into exile. He expected that things would settle and that those involved had been dealt with.

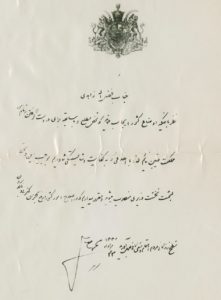

Washington and London had told Kermit Roosevelt Jr. to call off the actions and flee after the failed coup, but he did not see failure as an option. Communication between the three had delays given the distance, so at this point Roosevelt was acting on his own intuition. He had two firmans (orders) created which dismissed Prime Minister Mossadegh and named General Fazlollah to replace him, signed with the authority and power of the Shah. Although this was not technically legal since the Majlis had to vote on the issue, it was done to give some legitimacy in the public eye to the actions incited by this secret network of agents. These firmans were distributed across the country, sending the public into confusion and chaos.

The Rashidian brothers had been key players on the ground in Iran. They were inciting resentment in Tehran and organizing some crucial participants for what was to come. They recruited public figures who would be able to turn out crowds at a crucial moment. Propaganda was created both against Mossadegh and the Shah. The intention behind creating a negative image of Mossadegh was clear. But the team of agents created negative images of Mohammad Reza Shah to make it look as if Mossadegh had sent the Shah into exile as a power move. Either way, public opinion was irrelevant as long as there was enough disorder (Wilber, IV & V).

People had already taken the streets. Pro-Mossadegh sympathizers made their way to Tehran, the nation’s capital. The situation had gotten so disorderly that protesters tore down a statue of the Shah. There are no measurements of how many protesters were paid or there on their own account. Prime Minister Mossadegh took no actions against demonstrators, saying it was their right to free speech. Kermit Roosevelt Jr. was so surprised by Mossadegh’s lack of action and casual attitude that he thought it necessary to get U.S. Ambassador Loy Henderson to call upon Mossadegh. Henderson met with him to complain that Americans in Iran had felt terrorized by protesters. “Americans had organized the upheaval in Iran, but Henderson was portraying them as its victims” (Kinzer). The Prime Minister was still unaware of the United States’ role in the mayhem and still admired Americans. Mossadegh responded by banning all public demonstrations. He called upon his supporters to stay home.

The following day, August 19th, 1953, paid demonstrators hit the streets of Tehran. Public figures, including Ayatollah Kashani, that had been approached by General Zahedi and the Rashidian brothers, called their supporters to take the streets as well. Many of those who participated were swayed by the firman that was issued, and obeying the wishes of the Shah. They were exclaiming statements that were pro-Shah and anti-Mossadegh. Supporters of Mossadegh were not there to create a counterprotest out of his wishes the previous day.

Riots and buildings were burned down, and radio stations and government buildings were seized. Roosevelt called on his CIA agents to broadcast a message through seized media sources that Mossadegh had fallen and Zahedi was named the new Prime Minister. It was a pre-emptive message. As the message was given, military units enlisted by Zahedi were cornering Mossadegh in his house (“British memorandum”). Officers who were loyal to Mossadegh would have come to defend him, but the broadcasts hid the truth. After several hours of assault and conflict on Mossadegh’s property, it came to an end. Mohammad Mossadegh was able to escape at the last minute and went into hiding. Over 300 people were killed and many more injured on August 19, 1953.

The Shah and the New Prime Minister

The following day, Mohammad Mossadegh turned himself in. The new Prime Minister, Fazlollah Zahedi, was quick to consolidate his power, he ordered that all pro-Mossadegh officers be dismissed. Yet he continued to treat Mossadegh with the utmost respect and kindness while Mohammad Reza Shah condemned him, calling him the force of true evil. Mohammad Reza Shah was quick to assume his importance and significance, thinking that what had transpired was solely in the name of the Shah.

Mohammad Mossadegh was sentenced to three years of prison and confined for life to his home village. The Shah made sure that all dissent was silenced.

Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi grew to become a powerful dictator through the direct financial support and indirect tolerance of the United States. He created the secret police called the Savak, that operated outside of the law and harassed the population into fear. The Shah implemented western policies and social reforms that favored foreign influence and corporations. He displaced a significant part of the population through land reforms which made room for industrial development, during what was called the White Revolution, that began in 1963.

After 20 years following the fall of Mossadegh, the oil was successfully “nationalized.” Iran came to be an extremely wealthy nation, but its wealth accumulated at the top with the Shah and those by his side. The majority of the Iranian population remained to be extremely impoverished as inequality was exacerbated by the Shah’s policies. The Shah lived a luxurious life, throwing millions of dollars on parties while his regime failed to provide people with access to basic necessities. Mohammad Reza Shah and the United States had cozied up together into a powerhouse of exploitation (Shirazi).

The true nail in the Shah’s coffin were his actions that intentionally isolated religious leaders. He blatantly disregarded the role of Islam in Iran and inhibited genuine religious freedom of the Shi’ite majority population. His secular western policies and pre-Islamic cultural glorification created much resentment. He was an oppressive dictator that was supported by the United States, which set the stage for the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

Conclusion

One must look at the history of British and United States intervention and its outcomes, to understand the history of Iran. In order to prevent an example of a country that nationalized its primary resource, oil, the United States deposed Iran of its only democratic government and supported a corrupt dictator in its place. The intention of the coup against Mohammad Mossadegh was to secure a strategic ally and resource in the Middle East. Although that was the case for a few decades, the oppressive regime of the Shah led Iranians to launch the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

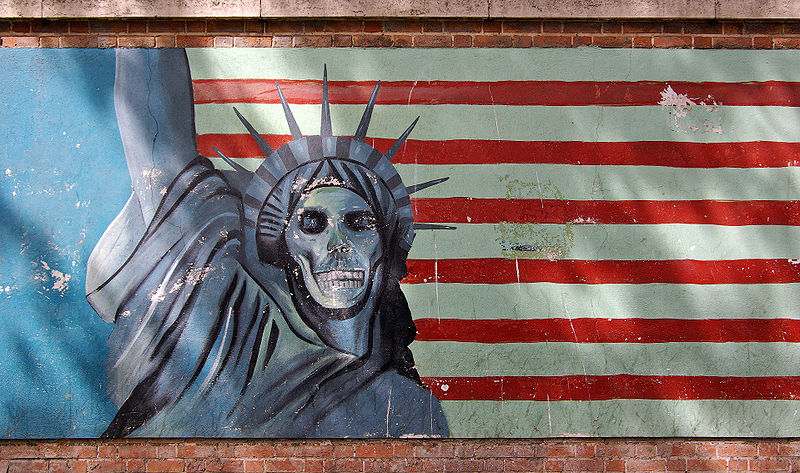

The Revolution brought to power the exiled religious cleric, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who was extremely anti-Western. Iranians will never forget the role the United States played in the demise of their democracy and oil wealth. The governments of Iran following Prime Minister Mossadegh were extremely repressive to prevent any political upheaval. “By publicly appropriating funds for a program aimed explicitly at destabilizing the Iranian regime, the United States has helped to set off a fierce crackdown on dissent, narrowed the space for democratic development in Iran, and sat back the cause of freedom to which it claims to be committed” (Kinzer). Diplomatic relations between Iran and the United States appear difficult given their complex history. It would be foolish to ignore the effects of U.S. policies that have shaped Iran into what is is today. Whether on a macro or micro scale, it is crucial to look at the long term effects of one’s actions. When a mistake is made, it should be learned from and not continued behavior while expecting different results.

“There is nothing new in the world except the history you do not know”

-Harry Truman.

Sources

Behrooz, M. (2000, November 4). Rebels with a cause: The failure of the Left in Iran. London & New York: I. B. Tauris.

British memorandum: Persia, A political review of the recent crisis. (1953, September 2). In Foreign relations of the United States, 1952-1954. Iran, 1952-1954: Volume X. United States Department of State. Office of the Historian.

Cooper, A. S. (2011). The oil kings: how the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia changed the balance of power in the Middle East. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Fisk, R. (2005). The great war for civilisation: the conquest of the Middle East. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Dixon, C. (2014). Another politics: talking across today’s transformative movements. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Humphreys, R. S. (1999). Between memory and desire: the Middle East in a troubled age. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Juhasz, A. (2008). The tyranny of oil: the world’s most powerful industry–and what we must do to stop it. New York: William Morrow.

Kinzer, S. (2008). All the Shah’s men: an American coup and the roots of Middle East terror. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kumar, D. (2012). Islamophobia and the politics of empire. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Mansfield, P., & Pelham, N. (2013). A history of the Middle East. New York: Penguin Books.

Mina, P. (2004, July 20). Oil Agreements in Iran (1901-1978): their history and evolution. Encyclopedia Iranica.

Memarsadehgi, A. (2007, April). The Nationalizing of Iranian Oil- An Economic Analysis. Berkeley.

Pahlavi dynasty. (2015, March 14). New World Encyclopedia.

Truman, H. (1951, July 8). President Truman to Prime Minister Mosadeq. United States Department of State. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952-1954. Iran, 1952-1954. Vol. X, p. 84-85. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1952-1954

Said, E. W. (2004). From Oslo to Iraq and the road map. New York: Pantheon Books.

Shiraz, N. (2014, February 14). The forgotten history of American support for the Shah. Muftah.

Sreberny, A., Torfeh, M. (2014). Persian Service: The BBC and British interests in Iran. London & New York: I.B. Tauris.

Voltz, D. (2009, January 19). Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. New World Encyclopedia, . Retrieved 04:49, February 5, 2017.

Wilber, D. N., Central Intelligence Agency. (1954, March). Appendix B: “London” draft of the TPAJAX operational plan. In Overthrow of Premier Mossadeq of Iran: November 1952 – August 1953. The New York Times.

Wilber, D. N., Central Intelligence Agency. (1954, March). Section I: Preliminary steps. In Overthrow of Premier Mossadeq of Iran: November 1952 – August 1953. The New York Times.

Wilber, D. N., Central Intelligence Agency. (1954, March). Section IV: The decisions are made: Activity begins. In Overthrow of Premier Mossadeq of Iran: November 1952 – August 1953. The New York Times.

Wilber, D. N., Central Intelligence Agency. (1954, March). Section V: Mounting pressure against the Shah. In Overthrow of Premier Mossadeq of Iran: November 1952 – August 1953. The New York Times.

Wiley. (1949, August 9). The Ambassador in Iran (Wiley) to the Secretary of State. United States Department of State. Foreign relations of the United States, 1949. The Near East, South Asia, and Africa. Vol. VI, 1949, p. 552-555. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949.