Roma Castellanos

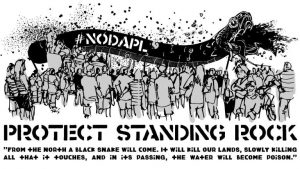

The resistance at Standing Rock has caused ripple effects around the world (see Standing Rock) . Just weeks after the week-long Port protest here in Olympia, Washington, the Obama administration temporarily denied an easement permit for the Dakota Access Pipeline to drill under the Missouri River at sacred Lake Oahe. The resistance to fossil fuel development is growing quickly around the country.

In Texas, where I was born and raised, the Society of Native Nations and the Big Bend Conservation Alliance are assembling a camp inspired by Oceti Sakowin, the Indigenous prayer camp at Standing Rock, to protect the border’s waterway, known as the Rio Grande, from the Trans-Pecos Pipeline (TPPL). The TPPL project is being led by Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), the same company being opposed in North Dakota. This fight against another “Black Snake” takes place in the Chihuahuan Desert where a few of the 43 Texas ranchers to have their land threatened by eminent domain invited a coalition of Indigenous activists and environmentalists to set up a prayer and resistance camp. They call it Two Rivers, but the local Indigenous peoples refer to it as La Junta de los Rios (The Rivers Together), an allusion to the true nature of the Rio Grande.

“Opposition to Trans-Pecos escalated over the last two years. It started with local coalitions and landowners pressuring federal and state regulators, and challenging the use of eminent domain in courts. But tactics have shifted to mirror the example set by the Oceti Sakowin camp in North Dakota. Indigenous-led prayer ceremonies and lockdowns on machinery, all broadcast over social media, have stalled work in Texas and brought attention to the campaign. So far, police have arrested at least six people for attempting to stop construction” (PBS Newshour).

The video above shows Frankie Orona from the San Antonio-based Society of Native Nations (SNN). Orona and Pete Hefflin, also from SNN, are crucial organizers at the camp.

“‘The closing of the camp [Oceti Sakowin] is not the end of a movement or fight, it is a new beginning,’ said Tom Goldtooth, executive director of the Indigenous Environmental Network. ‘They cannot extinguish the fire that Standing Rock started.’ Protesters said they might shift their attention to the Sabal Trail pipeline, which would ship natural gas from Alabama to Florida, or the Trans-Pecos line in West Texas and the Diamond Pipeline, which would run from Oklahoma to Tennessee” (Sylvester).

Coming Together

It is important to understand the timeline of events leading up to the current resistance in Texas. Of course, there are actually multiple timelines and if they were drawn out they might be reminiscent of the rivers themselves, running along, moving mountains, seemingly separating us, but in reality bringing us together. Part of the timeline can be seen in the geography of the region.

(Credit: Moon Travel Guides)

The familiar shape of Texas actually represents a massively diverse ecosystem, connected to the south by the great Rio Grande (Río Bravo in Mexico). Our focus is on the El Paso, West Texas, and Big Bend regions.

Here, the sister cities of Presidio and Ojinaga mark the confluence of the Rio Conchos and Rio Grande, forming a desert oasis in the shadow of the Trans-Pecos Mountains.

Energy Transfer Partners makes it all but impossible to understand the truth around the pipeline project. Their website “transpecospipelinefacts.com” should only be used as a tool for generating responses to popular arguments such as job creation and energy independence.

Here’s what’s really going on.

La Resistencia

Black Snake

“The pipelines are the dark fulfillment of an ancestral Lakota Sioux prophecy they call the Black Snake” (Bengal).

(Credit: Guise of Fawkes)

It can be distracting to immerse oneself in the propaganda of the pipeline companies. However, there is value in understanding their frameworks, protocols, and “following the money” by identifying the role stockholders, board members, and politicians play in influencing their decision-making.

There are three partners involved in the Trans-Pecos project that make up what they call a consortium. The first is Grupo Carso; also called Grupo Sanborns SAB, this global, conglomerate company is owned by Carlos Slim Helú, the “richest man in Mexico.” His empire is known to engage in the retail, industrial, and construction business (Shaefer).

“Despite promises to Texans by ETP and Carso Group Chairman and CEO Carlos Slim that all of the fracked gas is intended for Mexico, those connected with TPP now admit that the end goal for much of the exported gas is a new liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility on Mexico’s Pacific coast” (DeSmogBlog).

The Young Turks Politics reporter Jordan Chariton is the only journalist covering the TPP consistently. He discusses Carlos Slim’s influence in the video below making the connection between the privatization of Mexican oil, Trans-Pacific trade deals, and global politics.

Kelcy Warren

The second head of the Black Snake is Energy Transfer Partners CEO Kelcy Warren. Warren worked in the natural gas industry and became co-chair of Energy Transfer Equity in 2007. With business partner Ray Davis, co-owner of the Texas Rangers baseball team, Warren built Energy Transfer Equity into one of the nation’s largest pipeline companies, which now owns about 71,000 miles of pipelines carrying natural gas, natural gas liquids, refined products and crude oil. The company’s holdings include Sunoco, Southern Union and Regency Energy Partners.

Forbes estimates Warren’s personal wealth at $4 billion. Bloomberg described him as “among America’s new shale tycoons” — but rather than building a fortune by drilling he “takes the stuff others pull from underground and moves it from one place to another, chilling, boiling, pressurizing, and processing it until it’s worth more than when it burst from the wellhead” (Sturgis).

when talking to people back home in Texas, one of the main arguments I hear for oil pipelines is job creation. Their understanding is fundamentally flawed because the jobs created by pipeline construction are given to transient workers from the outside, and when construction is complete these workers move on, leaving only debris behind. MasTec Inc. is the company in charge of staffing for the TPPL project and can be considered the third head of the Trans-Pecos Black Snake. They’ve supplied the approximately 350 temporary workers on the project (DeSmogBlog).

(De)Regulation

Federal regulators on both sides of the river are partial to completing the pipeline. Mexico’s Federal Electricity Commission awarded the nearly $770 million contract to Slim and Warren in February 2015. Its reasoning was that the project will bring “much needed” natural gas to Mexico where residents are reliant on propane, coal, and wood power. In reality, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s 2013 assessment of world shale gas resources, Mexico already had an estimated 545 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable shale gas resources — the sixth largest of any country examined in the study (DeSmog Blog).

The U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) is just as fraught with corruption. Despite a massive letter writing campaign called Dear FERC with over 1,200 statements, the permit was granted allowing construction to proceed. A prophetic photographer, Jessica Lutz, was able to document the project as an offshoot of her ongoing explorations into border communities. Below are some of the crucial comments made in the Dear FERC project.

For the pipeline to be built across the Rio Grande it should be considered interstate, but ETP avoided this classification and was able to convince the Texas Railroad Commission to consider the pipeline intrastate, requiring only a T-4 form instead of the more complicated Presidential Permit. The Texas Railroad Commission is extremely lenient towards energy developers and granted the permit for intrastate construction in April 2015, just a month after landowner notifications were sent out (Schatz).

Another way the Black Snake avoids regulation is the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case, which made it easier for multinational corporations to contribute unlimited sums of money to political campaigns. Thus, Kelcy Warren was able to contribute to a political climate in Texas which favored pipeline projects.

Revolving Door

In November 2016, Democracy Now’s Amy Goodman sat down with Sue Sturgis, editorial director of Facing South and author of a recent piece headlined “Meet the Texas Billionaire and GOP Donor Behind the North Dakota Pipeline Controversy.” Below is an excerpt from the interview which illustrates how politics in Texas and the country as a whole are shaped by these contributions (read: bribes).

[Warren’s] donated millions of dollars to politics at both the federal and state levels, and much of that money has gone to Republican politicians. During this election cycle, as was mentioned, he’s donated at least $500,000 to Rick Perry’s presidential campaign. And since the primary, he has donated at least $100,000 to organizations that support Donald Trump. Then, also, at the state level, he has been a big supporter of Governor Greg Abbott of Texas, and last year Abbott appointed Warren to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission.

And at the same time that Kelcy Warren is making campaign contributions, Energy Transfer Partners has its own PAC that’s also making contributions. So you have this sort of synergistic thing happening between, you know, the contributions, the investments from Warren and from the company, and politics. And during this election cycle, Energy Transfer Partners has invested about $300,000. That’s what we know of so far. Of course, these are moving figures; we’ll probably find out more after the election, when all the reports are in. But about $300,000 to federal candidates, and that’s primarily House and Senate candidates. And then the company is also making investments in state politics, about $100,000 this election cycle so far (Sturgis).

Music and Vibration

There’s another timeline which crosses back-and-forth with the project timeline that involves local and world-famous musicians on both sides of the issue.

Warren owns a music studio and label in Austin and organizes the annual Cherokee Creek Music Festival at his Hill Country ranch between Llano and San Saba.

Jackson Browne performed at Warren’s Cherokee Creek Music Festival in 2011, but has since made it clear that he will not play for Kelcy Warren for the foreseeable future:

“Jackson Browne has stood in solidarity with Native peoples protecting their lands, water and lifeways for more than 37 years. His work to support Native-led efforts to protect the Earth began in 1979 when he came to the Black Hills and Four Corners area to help stop uranium mining. Through the decades, he has lent his voice, his talent, his time and his fame to raise awareness and funds for Native communities working for a safe and healthy future for us all. Thank you, Jackson, for continuing your stand and for supporting the resistance at Standing Rock” (ICMN Staff).

“I do not play for oil interests. I do not play for companies who defile nature, or companies who attack demonstrators with trained attack dogs and pepper spray. I certainly would not have allowed my songs to be recorded by a record company whose owner’s other business does what Energy Transfer Partners is allegedly doing—threatening the water supply and the sacred sites of indigenous people” (Browne).

Other musicians speaking out against the pipeline include Emily Saliers and Amy Ray, better known as the folk duo Indigo Girls, Shawn Colvin, Joan Osborne, Keb’ Mo’, Scrappy Jud Newcomb, James McMurtry, and Patty Griffin.

Education and Oil

Texas public schools are also on both sides of the issue.

The Texas Economic Development Act, the state’s largest corporate welfare program, has grown rapidly over the last decade and will cost taxpayers at least $8.5 billion in property tax breaks to businesses through its lifetime, according to a Texas Observer analysis of data from the comptroller’s office. That’s money that comes out of the struggling public school finance system. Last year, Chapter 313 bled $326 million from Texas schools, and it’s projected to grow to $1.1 billion per year by 2022.

Commonly called Chapter 313 for its place in the tax code, the program was created by the Legislature in 2001 based in part on a typo in a report that showed Texas losing its competitive edge to other states. Lawmakers believed that Texas needed to offer big breaks on property taxes to lure business to the state. Under Chapter 313, school districts can strike deals with corporations to reduce their property tax obligations by up to 90 percent for 10 years. Because the state picks up the tab and companies often sweeten the pot with supplemental payments, there’s little incentive for school districts not to agree.

There is no limit to how much Chapter 313 could cost the Texas public school system. As the Observer has reported, the comptroller’s office, which oversees the program, almost never rejects a proposal, routinely signing off on tax breaks to companies that couldn’t have located in another state or were already planning to build in Texas (Sadasivam).

La Junta De Los Rios

So far I’ve outlined the main threats posed by the pipeline and pipelines in general, but the real story is how history is repeating itself, first in North Dakota and now in Texas. In North Dakota we saw a stand-off at Standing Rock reminiscent of the 1973 Wounded Knee stand-off in South Dakota. In Texas, the history being repeated goes back to Native peoples’ first encounters with Spanish colonists.

The University of Texas Press, which leases land for oil development, published a regional history text titled, The River Has Never Divided Us: A Border History of La Junta de los Rios.

Not quite the United States and not quite Mexico, La Junta de los Rios straddles the border between Texas and Chihuahua, occupying the basin formed by the conjunction of the Rio Grande and the Rio Conchos. It is one of the oldest continuously inhabited settlements in the Chihuahuan Desert, ranking in age and dignity with the Anasazi pueblos of New Mexico.

In the first comprehensive history of the region, Jefferson Morgenthaler traces the history of La Junta de los Rios from the formation of the Mexico-Texas border in the mid-19th century to the 1997 ambush shooting of teenage goatherd Esquiel Hernandez by U.S. Marines performing drug interdiction in El Polvo, Texas. “Though it is scores of miles from a major highway, I found natives, soldiers, rebels, bandidos, heroes, scoundrels, drug lords, scalp hunters, medal winners, and mystics,” writes Morgenthaler. “I found love, tragedy, struggle, and stories that have never been told.” In telling the turbulent history of this remote valley oasis, he examines the consequences of a national border running through a community older than the invisible line that divides it (Morgenthaler).

It’s clear that the land and the rivers have a way of connecting us. The pipeline and the wall have brought on a new wave of cooperation between communities of water and earth-protectors on both sides of the river.

Archeologists such as David Keller have been researching La Junta settlements like Trap Springs and are concerned that burial sites and other historically significant and sacred places will be desecrated by pipeline construction.

Residents of Alpine, Marfa, Fort Stockton, Terlingua, Lajitas, Boquillas del Carmen, Ojinaga, Fort Davis, Balmorhea, Austin, San Antonio, Houston, Dallas and rural residents of Brewster, Pecos, Reeves, Jeff Davis, and Presidio Counties have been marching and participating in direct actions against the pipeline since 2015. The direct descendants of Native peoples from Texas and Chihuahua, as well as Indigenous water protectors from Standing Rock, have taken the lead in prayer and song providing a powerful spiritual connection to the land which goes back farther than the borders that separate us today.

The McDonald Observatory and Big Bend National Park have a vested interest in the land and water as well. Some of the locals have also been here for generations and have developed a deep connection to La Junta. The Big Bend Conservation Alliance (BBCA) published a report, Threats Related to Industrialization of the Big Bend Region – A Focus on The Southern Delaware Basin Energy Development Activity, outlining the many threats industrialization poses to the Big Bend Region.

The southern Delaware Basin region borders the Jeff Davis, Presidio, and Brewster county region, “home of the Big Bend,” which includes Davis Mountains State Park, Big Bend Ranch State Park, the Chinati Mountains Preserve, Big Bend National Park itself, and the University of Texas McDonald Observatory, one of North America’s premier research astronomy facilities. These parks, and the research facility are part of an area tourism draw that brings in more than 100,000 visitors to the region annually – dark-sky tourism is a critical component of the regional economy. Artificial sky-brightness, and light sources, including flaring activity, industrial lighting, and commercial lighting all threaten to dramatically increase artificial sky-glow, and negatively impact this region, which has one of the darkest skies in North America. As potential development of the southern Delaware Basin pushes further south, these light sources move closer to the parks and observatory – light transmission and brightness is based on what is known as the “inverse square law” – in other words, a light source that moves twice is close to the viewer’s eye is four times brighter. A source that moves three times closer is nine times brighter, and so on. Currently, the artificial sky-glow, and associated light dome from the greater Permian Basin region is visible on the horizon from approximately 300-miles to the north-northeast. The Delaware Basin activity will push these sources of light to within 25-miles of these parks and research facility. While it is true that the surrounding seven counties are afforded legislative protection for night sky, and outdoor lighting, enforcement is problematic, and certain activities, like flaring are exempt from the associated legislation and ordinances.

In addition to increased sky-glow, threatening the region’s dark skies, reduced air quality, due to combustion by-products from rig and site power, fugitive emissions, and flaring, water demands, and potential contamination of groundwater resources, increased dust from traffic on unpaved lease roads, wear & tear on county and state roads from oilfield traffic, increases in vehicle accidents, including fatalities, increased crime, and corresponding increased demands on area public safety, EMS and fire resources (BBCA).

Water protectors at Two Rivers recognize that the odds of stopping the Trans-Pecos Pipeline completely are slim. However, Orona and fellow organizer Lori Glover believe they can impact pipeline policy and divestment from banks that support pipelines. Cities such as Seattle, Washington and Davis, California are moving to cut ties with Wells Fargo, a lender to the Dakota Access Pipeline (Beauvais).

“Success is not just measured in terms of whether a pipeline is stopped or not stopped,” Glover says. Glover is an organizer for the Big Bend Defense Coalition. She owns the land currently hosting the Two Rivers Camp. “This way of living that is not sustainable, that uses up all the resources, the only way to change that is through shifting our culture, changing our cultural belief systems,” she says. “And so that’s what working with the Native Americans is doing, that’s what having this camp is doing” (Beauvais).

Chief William Hoff of the Tsalagiyi Nvdagi said the Bird’s Fort Treaty of 1843 signed with the Republic of Texas guaranteed hunting and subsistence rights of the Native peoples of Texas, but was not honored when the Republic became a state. “Big oil and gas and nuclear will destroy our plants, animals, water, and air. So, to me that is a violation of that treaty,” said Hoff (Van Horn Advocate).

As of February 24, 2017, 16 people have been arrested and as of February 27, 2017 Pete Hefflin (SNN, AIMCTX) is being held at the local police department for no apparent reason.

According to Energy Transfer, the Trans-Pecos Pipeline is more than 96% complete making it “on schedule” to be in service by the end of next month (March 2017).

Mni Wiconi

Sources

Anonymous Contributor. (2016, November 12). Olympia, WA: North Dakota Fracking Equipment Blocked, Train Tracks Barricaded. It’s Going Down.

Baker, P. (2017, January 24). Trump Revives Keystone Pipeline Rejected by Obama. New York Times.

Beauvais, S. (2017, February 24). Protesters Continue Direct Action Planning as Pipeline Nears Completion. Marfa Public Radio.

Bengal, R. (2017, January 24). Congratulations, Donald Trump, You Just Reignited the DAPL Resistance. Vogue.

Big Bend Conservation Alliance. (n.d.). Threats Related to Industrialization of the Big Bend Region – A Focus on The Southern Delaware Basin Energy Development Activity. BBCA.

Birnel, A. UT System has financial ties to Trans-Pecos pipeline. The Paisano.

Bubenik, T. (2017, January 9). With Lack of Details, Border Landowners Contemplate What a Wall Would Mean. Texas Standard.

Buhl, L. (2017, February 3). Where Is Fracked Gas Really Headed as It Passes Through Texas’ Trans-Pecos Pipeline? DeSmog Blog.

Camp of the Sacred Stones. (2017, January 1). Standing Rock to the World: 10 Indigenous and Environmental Struggles You Can Support in 2017. SacredStoneCamp.

Energy Transfer. (2017, January 25). Trans-Pecos Pipeline Project. Energy Transfer.

Goodman, A. (2016, November 3). Who is Kelcy Warren, the Texas Billionaire and Folk Music Fan Behind the Dakota Access Pipeline. Democracy Now.

Gruley, B. (2015, May 18). Pipeline Billionaire Kelcy Warren Is Having Fun in the Oil Bust: The founder of energy transfer partners has built his $7.3 billion personal fortune by making smart moves during the industry’s ‘dark times’. Bloomberg.

Guise of Fawkes. (2016, November 10). New Orleans, NOV13th: Guise of Fawkes Krewe New Blood Membership Meetup #NODAPL.

Lutz, J. Transpecos Pipeline: Lives on the Line. Dear FERC.

Monroe, R. (2015, May 13). An unlikely alliance: Ranchers and green activists fight Texas pipeline. Aljazeera America.

Morgenthaler, J. (2004, May 1). The River Has Never Divided Us: A Border History of La Junta de los Rios. Jack and Doris Smothers Series in Texas History, Life, and Culture.

Mosqueda, P. (2015, February 16). The Holdouts: Three families who took a pass on the fracking boom – and what it cost them. Texas Observer.

Rhodes, A. (2014, January 25). Texas Slang and Twang: How to Talk Like a Texan. Moon.

Sadasivam, N. (2017, February 13). Texas’ Largest Corporate Welfare Program is Rapidly Ballooning. Texas Observer.

Scialla, M. (2017, January 18). New pipeline clashes call on Standing Rock playbook. PBS Newshour.

Schatz, B. (2015, May 15). The Pipeline That Texans Are Freaking Out Over (Nope, Not Keystone). Mother Jones.

Shaefer, S. (2016, May). The World’s Biggest Public Companies: Grupo Carso. Forbes.

SNN. (2016, October 29). Two Rivers Camp – “Stop the trans pecos pipeline”. Society of Native Nations.

Sturgis, S. (2016, September 7). Meet the Texas billionaire and GOP donor behind the North Dakota pipeline controversy. Facing South.

Sylvester, T. (2017, February 25) Dakota protesters regroup, plot resistance to other pipelines. Reuters.

Texas Beyond History. La Junta de los Rios: Villagers of the Chihuahuan Desert Rivers. TexasBeyondHistory.net.

Van Oldershausen, S. (2015, March 12). The landmen cometh: surveyors make first move on Trans Pecos pipeline. Big Bend Now.