Jaxson Merk

What is Intersectional Health?

The term “intersectionality” is most famously known through the term intersectional feminism. The term was formulated by African American Policy Forum and a professor of law at Columbia University and the University of California, Los Angeles, Kimberle Crenshaw, who states that,

“Intersectionality is an analytic sensibility, a way of thinking about identity and its relationship to power. Originally articulated on behalf of black women, the term brought to light the invisibility of many constituents within groups that claim them as members, but often fail to represent them. Intersectional erasures are not exclusive to black women. People of color within LGBTQ movements; girls of color in the fight against the school-to-prison pipeline; women within immigration movements; trans women within feminist movements; and people with disabilities fighting police abuse — all face vulnerabilities that reflect the intersections of racism, sexism, class oppression, transphobia, able-ism and more. Intersectionality has given many advocates a way to frame their circumstances and to fight for their visibility and inclusion” (Crenshaw).

Using the intersectional model seemed more than appropriate when talking about HIV and AIDS in the United States. While the intersectionality model has grown to encompass many different narratives, it is important to note its creation was made to intentionally talk about the experience of black women.

Intersectional health grows on the model on inequality by focusing on power and visibility in regards to the medical field. This is still a major endeavor as the medical world encompasses many different aspects such as insurance, treatment, access, knowledge, and research. In regards to medical research,

“careful attention to intersectional issues has the potential to reduce measurement bias and improve construct validity, by identifying whether identity, position, process or policy variables are relevant, and thus avoiding inadvertent use of proxy variables. It can also help avert conceptual and interpretation biases in preventing misspecified levels and assumptions of equidistance from outcomes” (Bauer)

Intersectionality is even more important in scientific fields such as health. The medical field, since its privatization, has been a field dominated by those who had access to schooling, knowledge and funding. Those people are cis, white, straight, able-bodied, upper-class men. The findings of this group have always been viewed as neutral and factual. As the above quote states, intersectionality is vital in complicating this idea. Intersectionality can start to undo some of the pervasive ideas in the medical community, such as the idea that privileged identities provide neutral perspectives.

What is HIV/AIDS?

Stigma surrounding Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) also leads to widespread misinformation about them. Not only does false information get spread because of the stigma of HIV being a STD, it also is stigmatized because of its long, incorrect, history of being identified as a “gay” disease in the U.S.

Case Definitions of HIV and AIDS

HIV stands for Human Immunodeficiency Virus. There are three different Human Immunodeficiency Viruses, HIV-1 M and O, HIV-10, and HIV-2. HIV-1 M, main, is what has spread around the world and what most people are referring to when talking about HIV. HIV-10 and HIV-2 generally are only found in West Africa. These groupings are classified differently based on the DNA sequences of HIV located around the world (Smith, 262-264).

There are many infections that can be cleared by the immune system, however HIV is specifically a primate lentivirus. A lentivirus like HIV has the ability to target and infect CD4+ cells. CD4+ cells are also known as T cells or T-helper cells. They are the prime defense in locating and signaling the immune system when viruses or bacteria are found in your system. HIVs sole purpose is to find new cells to attack and replicate itself; the intention of HIV is not to kill its host but the decline of the immune system is an unintended side effect (Smith, 260).

The case definition for AIDS is tricky. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) originally described an HIV-positive person as also having AIDS when their “CD4+ cell count has fallen under 200 cells per microliter” (Smith, 58).

It was later revised in 1985 and included 20 other conditions, four cancers and 16 opportunistic infections. These opportunistic infections in a HIV-negative person may not be deadly at all but with someone who has a compromised immune system, such as someone with HIV, these infections are allowed to easily go unregulated by the body. In 1987, once again three more infections were added to the list these were tuberculosis that occurred outside the lungs, wasting syndrome, encephalopathy, and dementia. In 1993, the CDC was lobbied and three more conditions were added to the list including cervical cancer, recurrent bacterial pneumonia, and pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) (Smith, 58). The nature of when an HIV-positive person progresses to AIDS is very messy and complicated. It is easy to infer that the case definition of AIDS will change many more times in the years to come.

Origin of HIV and its Transfer to the United States

HIV most likely was a new virus that had mutated off of a different virus, also known as a crossover virus. The reason the original virus was not easily traceable was because it did not affect humans. In 1985 there was a breakthrough when the discovery of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus, SIVmac, was found in rhesus monkeys. SIVmac was shown to be very similar to HIV-1 and 2, but it did show closer linkage to HIV-2. While the rhesus monkeys were found to have SIVmac it was surprising that hardly any in captivity had it and no rhesus monkeys in their natural habitat in Asia did either (Smith, 262-264).

Another breakthrough came when realizing that the rhesus monkeys who did acquire SIVmac were accidentally infected by the rare West African monkey, the sooty mangabey. While the sooty mangabey may be SIV-positive their whole life they never acquire Simian AIDs. This is because SIV has been generationally carried by the sooty mangabeys allowing it to lie dormant in their systems. Studies in West Africa showed that sooty mangabeys in the wild and kept as pets had SIVsm. SIVsm was also very closely linked with HIV-2 most commonly isolated to West Africa (Smith, 262-264).

The complete link between SIV and HIV is still unknown, however all six subtypes of HIV-2 are found within the geographical location of SIVsm. Sooty mangabeys are also common household pets in West Africa and often are carriers of SIVsm. While SIV is an old disease HIV is still relatively new. The closest known link for SIV to turn into HIV was in World War II when reusable needles were introduced into rural African clinics. Enough needle reuse could allow SIV to mutate into HIV. SIV changed identification to HIV when it could be sexually transmitted and cause disease. If this was the flash point for HIV, air travel helped to spread the disease worldwide. HIV can also take a decade or longer to progress to AIDs making it tricky to study its origins (Smith, 262-4).

Responses to the AIDS crisis

Public and Media Response

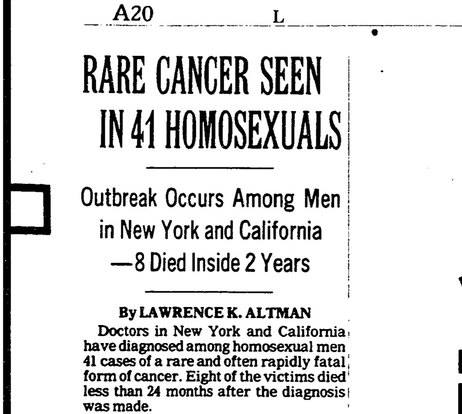

The first reports of HIV and AIDS in the US were documented on June 6th, 1981. The headline in the San Francisco Chronicle ran “A Pneumonia That Strikes Gay Males.” When these cases first started appearing the Center for Disease Control was puzzled. It was common that pneumonia was an opportunistic infection found in people with weakened immune systems. However, the people being infected now were supposedly strong, young and healthy. That left only one connection between the men experiencing this pneumonia, they were all not straight. The CDC would come out with a statement in the next few days stating “The fact that those patients were all homosexuals suggests an association between some aspect of a homosexual lifestyle or disease acquired through sexual contact and the pneumonia” (Eaklor, 174). The New York Times published a similar story less than a month later titled “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” This rare cancer was Kaposi’s Sarcoma. From these stories what is now referred to as HIV/AIDS as yet had no name.

This phenomenon was called “gay cancer”, “gay plague”, “4H” meaning it was thought to affect homosexuals, heroin addicts, Haitians, and hemophiliacs, and the more official title was GRID or “Gay-Related Immune Deficiency” (Eaklor, 174). These titles were released to the public and published for almost a full year before any official title was given to the disease. Even after HIV was given its formal title the public already made a strong connection between the disease and gayness, especially in the U.S. It took one year of misinformation and still 37 years later activists are still fighting that stigma.

Through the misrepresentation of the AIDS crisis and targeting of non-heterosexual people it “brought together, in ways tragic though revealing, generally unforgiving American attitudes in at least three areas: victims of circumstance, illness and disease, and sex and sexuality” (Eaklor, 175).

In regards to victims, it is a truly capitalist notion to put the blame unto the victim. Capitalism tied with the ideology of meritocracy means that if you have success, capital, or power you have worked hard and are deserving of it. This automatically means that if you do not have economic success, capital, or power you are attributed the opposite traits as those listed above. This idea has become an insidious thought process in every aspect of U.S. life, as we attribute everyone’s traumatic experiences as a defect in their personality. This is true of sexual assault, police brutality, homelessness, and was the response of a vast amount of the public in the AIDS crisis. “Americans are often critical of misfortune, it seems, with the brunt of hostility aimed at the unfortunate” (Eaklor, 176).

Since the early 1900s the United States has been obsessed with youth and health. This fixation on health has externalized costs. It requires those who are not healthy to become outcasts and not welcome in the public sphere. Health is also not a fixed idea, it is certainly not pure either, especially in America where the medical business is run by for-profit corporations. In fact, what is considered healthy sometimes has nothing to do with wellness of the self or the body. We can see this through America’s obsession with being thin. Being thin is not inherently healthy and fat people are often told that all of their symptoms are caused by their weight. Following the trending twitter hashtag #fatsidestories, there were countless tweets about doctors misdiagnosing and undertreating fat patients. This ranged from patients reporting having the flu and being told to lose weight all the way to being congratulated for dropping weight even when that weight loss was from disordered eating or illness (Kearns). Another externalized cost of worshiping health is that there is little care or concern for death and illness. In fact, there is a demonizing of being sick or ill (Eaklor, 176).

The most impactful reaction to the HIV/AIDS crisis was that it ignited a cisheterosexism not seen since before the Cold War. The sixties and seventies were dubbed as permissive and anti-family. The AIDS crisis became an outlet for all that pent-up hostility. Sex and sexuality were still relatively new topics to talk about in the public sphere, and they were for the most part still considered seriously taboo. Harassment and violence was directed towards folx who did not pass as cis or straight. In fact crime rates against the targets of cisheterosexism doubled between 1985 and 1986 (Eaklor, 176). Far-right leaders started dubbing homosexuals evil and deserving of AIDS, which also became known to them as the wrath of god. (Eaklor, 176).

Due to HIV being seen as a gay disease, people who contracted HIV and were not gay were also denied care. Most people who contracted HIV and were not gay also happened to be on the margins of society and were not extended public sympathy. This included injection drug users, poor, black, and/or brown people. Public hostility increased towards people who existed at the intersections of gay, trans, brown, black, disabled, poor, and/or injection drug user.

Government Response to HIV and AIDS

While the first reporting on the AIDS crisis was in 1981, it was not until 1985 that President Reagan even acknowledged it publicly. “More than 20,000 Americans had died from the disease [AIDS] by the time he [Reagan] first spoke about it” (Mosendz). In fact, the World Health Organization was holding meetings by 1983 (Mosendz).

On top of Republicans aligning with the Christian right, Reagan was also fiscally conservative and pushed a policy called New Federalism. New Federalism was a way to divest national spending and put more responsibility into state and local treasuries. Social programs, including public health were especially impacted by this. “Municipal responses, in turn, were directly related to the presence, size, and especially organization” of LGBTQ communities in their territory (Eaklor, 176). Through this policy LGBTQ people, had to prove they were worthy of treatment. Local governments, for the most part, ended up being even less attentive than the federal government.

LGBTQ Community Responses to HIV/AIDS

The lack of support from the public and the administration left the LGBTQ community in charge of their own care, mourning, and organizing. The LGBTQ community had limited energy and resources to provide for itself but action did take place. While there were divisions over tactics and goals organizing did happen. What was the GMHC (Gay Men’s Health Center) became the foundations for ASOs (AIDS Service Organizations). ASO was located in urban areas and had a strong focus not just on outreach and support but also worked towards treatment and prevention (Eaklor, 178).

Three LGBTQ-focused national organizations existed at the time. The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGTF) was the most active and well organized during the AIDS crisis. Human Rights Campaign (HRC) and Gay Rights National Lobby (GRNL) were both criticized heavily for not putting more focus onto the AIDS crisis. Later by the mid-’80s, HRC and NGTF worked together and separately to lobby congress for AIDS-related appropriations (Eaklor, 178).

In 1990, President George H.W Bush signed into law the Ryan White CARE (Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency) Act, and the Americans with Disabilities Act, which included protection for people with HIV or AIDS from discrimination (Eaklor, 178).

Perhaps the most influential group to organize was ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). Larry Kramer was the founder of this radical group, whose tactics deployed nonviolent direct action policies. Founded in March 1987, ACT UP New York drew more than 800 people to its weekly meetings, making it the biggest chapter. By 1988 chapters popped up all over the nation from Boston to LA. Their original goal was to have experimental AIDS drugs be released to the public and to bypass the Food and Drug Administrations (FDA) glacier slow approval process. ACT UP members described themselves to be united in anger. They promoted to radical democracy meaning there were no leaders, no one individual speaking for the group, and there was no formal structure. ACT UP was also partially responsible for reclaiming the term Queer.

ACT UP made a conscious effort to recruit women and minorities to its ranks. ACT UP women were responsible for making the CDC change the definition of AIDS to include HIV-positive women and injection drug users. ACT UP New York did have a hard time recruiting more brown and black folks. While there is not much written about the reason for this it is not hard to imagine in what ways social hierarchy went unchecked because there was no official hierarchy (Smith, 37-39).

ACT UP was influential through many different direct actions. Its contributions to AIDS-related public policy are innumerable. ACT UP forced the CDC to include women and injection drug users into the case definition of HIV/AIDS, it implemented clean needle exchange programs which have been proven to reduce HIV contraction, was effective in making sure AIDS medication was tested and distributed quickly from the FDA to the public, and pressured big pharma corporations to keep AIDS medication costs lower. Sadly, the group started splintering along the lines of those who wanted to take more traditional political routes and those who believed in more radical approaches. Many of the divisions experienced and also passing of members led to ACT UP not being viable anymore. While ACT UP is still around it does not have the same social capital as it did in the 1980s-90s. (Smith, 37-39).

Health at Intersections

It is messy to talk about intersectionality. It is impossible to section out identities into neat clean boxes. For any of the identities focused on below it is important to understand that there are people who exist in multiple categories, that there is not one overarching experience of a person with HIV/AIDS. There are rather overarching barriers to prevention, care, and treatment that can be talked about in regards to the identities listed below. Focus was given to the identities listed below because people in these categories are often overlooked and undertreated even though they make up a large population of new HIV/AIDs cases. Even with weeks of research the information listed below only provides an incomplete picture.

Black Women and HIV/AIDS

Focusing on black women is vital when talking about HIV and AIDS.

“Every 35 minutes, a woman tests positive for HIV in this country. Yet the impact of HIV among Black women and girls is even more startling. Nationally, Black women account for 66% of new cases of HIV among women. HIV/AIDS related illness is now the leading cause of death among Black women ages 25-34. As the national dialogue focuses on strategies for addressing the HIV epidemic in this country, the need is greater than ever for a heightened [concern] among Black women in HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and care” (BWHI).

Barriers to prevention, care, and treatment for black women intersect into many different areas. Abstinence-only education (or lack of any sex education) impacts young people’s ability to make sexual health decisions for themselves. While this may affect all teens it affects black women particularly because of underfunding in predominantly black schools. Teachers may not have the resources, knowledge, or permission to teach comprehensive sex education. Especially where federal funding is concerned sex education is heavily restricted. Black women also face barriers in the form of “disproportionate cutbacks in human and social services and racial discrimination in access to housing, living-wage employment, and quality educational opportunities” (Smith, 56).

A 2012 CDC report from the stated that “just over a third of HIV patients have steady care — 34 percent of African-Americans, 37 percent of Latinos and 38 percent of whites.” That means in the black community 66% of HIV-positive people are not receiving the care they need (NBC News).

The prison industrial complex and war on drugs also contribute to HIV and AIDS in black women. In concentrated areas of poverty, there is not only extreme national underfunding of education (as mentioned above) but also high rates of incarceration due the criminalization of poverty and black bodies. For black men who are incarcerated they may consensually or nonconsensually be exposed to HIV. Condoms and other forms of prevention such as PrEP are not easily attainable in prison, making it easy for HIV to spread. When these men leave prison they may unknowingly spread this infection to their sexual partners, putting black women at high risk for exposure. The war on drugs also added to this exposure as clean needle programs started to decline with the intensity at which drug crimes were persecuted especially in the black community. For black women who were injection drug users, it means availability of clean needles went down and HIV could spread easily through shared or reused needles. For black women who were not injection drug users it could mean that if any of their sexual partners were they may be prone to infection.

Black women are often lumped in with either all black persons or all women. This leaves black women an unfocused afterthought when their health needs to be prioritized. Where HIV and AIDS organizations should be centering the experiences of black women in prevention and care it is often left up to black women themselves to organize and care for each other. Black Women’s Health Imperative (BWHI) is an example of this. BWHI does work to educate black women around ailments that are more likely to affect them, such as HIV. They are an organization of black women medical professionals providing outreach, knowledge, and legislation to help inform and uplift black women’s health.

Trans Women and HIV/AIDS

Not only are transgender women undertreated but they are completely made invisible in statistics and other data regarding medical needs. This is extremely deadly for trans women because “more than one in four trans women – including more than half of Black trans women – are living with HIV. Globally, trans women are nearly 50 times more likely to have HIV as compared to other populations (Greater Than AIDS).

This is because transgender women in regards to HIV and AIDS research are put in the category MSM “men who have sex with men.”

The category MSM was created in an attempt to talk about the multiple sexualities that cis men who have sex with other cis men may hold. However it is deadly to lump transgender women in to the MSM category.

First of all, this category does not apply to transgender women, because transgender women are women. Calling trans women anything other than women is violent, as the medical community and the world so often is. In fact, the categorizing of trans women as MSM, even in the basic form of people who have penises having sex with other people with penises, is not true for all transgender women. Being transgender is not about who you are having sex with, it is about who you are as a person. Transgender women can be lesbians, bisexual, pansexual, straight, or any other identity, meaning they are not always having sex with someone who has a penis and they may also not have a penis themselves.

The CDC generally talks about HIV spreading in regards to MSM, Women who have Sex with Women (WSW), “Heterosexual Sex,” injection drug users, and mother to child during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Besides the last two all of these terms refer to very archaic notions of sexuality. This terminology leaves quite a few people to fall through the cracks. Not only does this wrongly categorize trans women, trans men, and any other non-cis person, it also alienates anyone who experiences attraction to more than one gender. A cisgender bisexual woman who contracted HIV from a cisgender bisexual man would be categorized under “heterosexual sex contraction” even though neither person identified as heterosexual. These archaic and violent categories become a deterrent for trans women to seek treatment.

“Surveys indicate that trans people frequently have unsatisfactory experiences with mainstream health services. Problems faced by trans patients include providers and administrative staff using improper pronouns to address them, lack of preparedness to address their unique health needs, and/or denial of health services entirely. As a result, many trans people either forgo health services altogether—sometimes even in life-threatening situations—or must travel considerable distances to obtain care from a knowledgeable and qualified provider” (Foundation for AIDS Research).

Trans women are higher targets for this kind of violence. While Trans Exterminatory Radical “Feminists” (TERFs), and conservative political parties target all of the trans community, trans women face the most of this violence, especially trans women of color.

Commonalities

In regards to both of these groups, poverty and lack of education on top of misogynoir and trans-misogyny, are what keep these groups from being treated. 75% of people with HIV lack the proper health care (NBC). Black women are 17.8% more likely to live in poverty than white women (Guerra). Trans people, specifically women, are four times more likely to have an income of $10,000 or less per year (Kellaway). Sex education is highly underfunded in predominantly black schools, and even in well-funded schools, comprehensive queer and trans inclusive sex education is rarely, if ever, provided. Of both of these groups it is most important to remember that black trans women are doubly affected by cissexism and misogynoir (see : Trans Bodies as Commodities in the Medical World).

Incorporating Intersectionality into Health

HIV provides a greatly detailed picture of why intersectionality is vital to talking about health care in the United States. HIV treatment from the beginning of its documentation in the United States has been wrought with lack of concern for the people it affected and affects most heavily. Originally thought to only affect cis gay men, the general public was not concerned with the deaths of those they deemed amoral or deserving, especially if those cis gay men were effeminate, black, brown, disabled or of any other devalued identities. Even now that medically it is known HIV is not a disease only contracted by cis gay men, those most affected are not being centered. It is also not surprising that the most new HIV infections happen in some of the most systematically undervalued groups including black women, trans women, and black trans women.

The medical world does not exist outside of systematic oppression in the U.S. Until we see an end to the school-to-prison pipeline, the prison industrial complex, medical and systemic racism, cissexism, criminalization of injection drug users, criminalization of poverty, underfunding or banning comprehensive all-inclusive sexual education, and many more factors of structural oppression we will not see proper care for those who have HIV or an end to HIV. Intersectional healthcare is not possible when healthcare is commodified. Until healthcare is not commodified there are groups doing the ground work to provide outreach such as the BWHI, and Center of Excellence for Transgender Health (CoE). However, a discussion about ending HIV infection is inextricably linked to the decommodification of healthcare and the end of capitalism.

Sources

Heywood, Todd. (2014, April 30). Words Matter: Why The Misgendering and Erasure of Trans Women Is Literally Killing Them. HIVPlusMag.