Taylor Maschger

The global expansion of capitalism has generated the creation of organizational structures within many cultures and societies that favor individualism, rather than collectivist beliefs. Many groups, especially those already faced with certain marginalization, are left behind to fend for themselves as their communities, ecosystems, and cultural identities are ravaged in perpetuity of the corporate model of economic exploitation and abandonment (What is a Worker Cooperative?). In the wake of the Great Recession, with an ever-increasing wage gap and “the economic trend toward a service economy,” more and more people are becoming trapped in a cycle of precarious employment – most notably, immigrants (Creating Better Jobs). In spite of this, or perhaps in response, a rapidly growing number of immigrant-led democratic workplaces are springing up around the globe as “a form of resistance to economic marginalization” (Wilson, 26). These workplaces are known as worker cooperatives.

What are Worker Cooperatives, and How Do They Function?

Worker cooperatives are founded on the principles of worker ownership and control, and strive to embody the values of “autonomy, participatory democracy, equality, equity and solidarity” (Wilson, 17). They are multifunctional in the sense that they most often aim to serve a variety of purposes, both social and economic, within a group or community. While the main purpose of worker cooperatives is to provide its members with employment, they also aim to empower those workers by building “alternative spaces of post-capital production based on worker freedom, autonomy and control” (Wilson, 38). In order to ensure democratic control of an enterprise, “each member purchases a share in the cooperative or pays a membership fee and has an equal vote with all other members,” which in turn provides worker-owners with the horizontal distribution of economic responsibility and decision-making power (Wilson, 17).

The worker cooperative model emphasizes the needs and services of its members, often assisting in “the development of social, human and financial capital” by blending “opportunities for gainful employment, increased savings and individual and community capacity-building with equity and social justice principles” (Wilson, 23). In fact, as stated by the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives, because they model empowerment and practice real democracy on a daily basis, “worker cooperatives can play an important role in building movements for economic justice and social change” (Ji & Robinson). Democratic practices within worker cooperatives most often come to fruition through the use of horizontal decision making processes such as consensus. Consensus is a cooperative and non-coercive form of decision-making intended to reflect the integrated will of a group or organization. It is a valuable tool for prioritizing and preserving the interests and integrity of individuals within a collective (Schutt).

Cooperatives offer worker-owners a sense of security in that decisions regarding the future of their business or enterprise are made entirely by themselves, not by workplace superiors without their involvement. In this way, the structure of worker cooperatives is frequently “considered by [sic] members to be more just because it offers them greater control of both their work life and personal life by allowing them to choose what, when, where and how they will labour” (Shifley, 105). Worker cooperatives can be an especially powerful apparatus for marginalized groups, such as immigrants, because they hold the potential to combat challenges such as poverty and precarious employment, as well as other forms of oppression and marginalization, through the provision of meaningful employment and economic security.

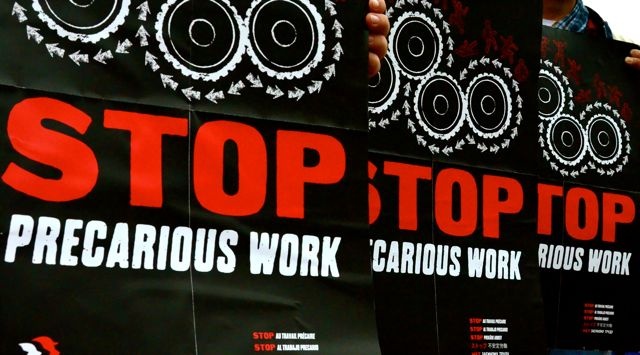

Precarious Employment and the Informal Economy

Today, many immigrants labor in the informal economy, defined by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) as “the diversified set of economic activities, enterprises, jobs, and workers that are not regulated or protected by the state.” This economic sector is dominated by jobs that are irregular, poorly paid, and highly susceptible to exploitation (Ji & Robinson). While these struggles are faced by all laborers in the informal economy, immigrant workers, and “[undocumented] immigrant workers, in particular, are vulnerable to exploitation such as wage theft, dangerous working conditions and extremely low wages due to their precarious legal status and position in the informal economy” (Ji & Robinson). According to a 2010 report conducted in Denver, Colorado, by El Centro Humanitario, “56% of immigrant domestic workers are paid less than minimum wage, 54% are regularly not paid for all hours worked, 25% work more than 50 hours a week without overtime pay, and 59% regularly experience verbal or physical abuse on the job” (Ji & Robinson).

With little to no access to resources such as banking loans, unions, or legal representation, immigrants become trapped in these precarious employment situations. The cycle of precarious employment, defined by “atypical employment contracts, limited social benefits and statutory entitlements, job insecurity, low wages, and high risks of ill health,” is catalyzed by the way in which work is organized under precarious employment relations (Wilson, 9). It points to the inability and unwillingness of corporate business models to grant workers control or autonomy in the workplace, or to consider the social needs of their workers. It is important to note that in addition to the denial of workplace benefits such as workman’s compensation or fair wages, “gender, ethnic, and racial discrimination are uncontrolled and systematically exploited” and there are “no mandatory health or safety regulations [to] protect workers from injury or death on the job” (Vogel, 29).

The informal economy and precarious employment cycle are preserved by the fact that immigrant laborers are unable to negotiate with employers for fair working conditions, as there will always be someone else economically desperate enough to work under exploitative conditions in order to meet theirs and their family’s needs. Undocumented immigrant workers also run the unique risk of inciting a workplace raid by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) if their employers are audited or decide to initiate a self-audit. Threatening to self-audit is a tactic most typically used by employers as a means of halting union organizing efforts amongst immigrant workers, or to terminate the renewal of a union contract.

Despite increasing hostility toward, and widespread exploitation of immigrant workers, states such as California, Texas, New York, and Illinois all have considerable established informal economies. Additionally, the “present pattern of illegal undocumented worker immigration in the United States signals a rapid expansion of the national informal economy” (Vogel, 36). The country’s unprecedented dependence on undocumented labor is made possible and political through “the widespread subversion of immigration and labor laws,” meaning that the “current wave of undocumented immigrants who work in the informal economy today are more likely than not to stay in the informal U.S. economy,” as opposed to being initiated into the mainstream U.S. working class (Vogel, 38).

Still, although state and local governments may acknowledge “the mounting evidence of systemic barriers facing immigrant workers” seeking acceptable employment, “the focus of government and employer strategies continues to be on the individual skills of immigrants, not on the structures of racism or precariousness in the labour market” (Wilson, 15). These strategies largely ignore the realities of immigrant workers, the deficit of decent jobs, and the structural causes of precarious employment. For this reason, it is crucial for immigrant communities to position themselves at the forefront of the struggle against precarious employment through the organization of worker cooperatives.

Funding and Outside Support

In order to understand their ability to serve as an alternative to precarious employment, however, one must analyze democratically-owned workplaces in relation to the broader networks of support and solidarity that exist. Many community organizations, “such as immigrant and refugee settlement agencies [and] employment-assistance programs…recognize the value and potential of workers cooperatives, and work to facilitate and encourage their organization and sustainability” (Wilson, 65). Due largely to socio-economic limitations, immigrants often lack the financial means and economic training necessary to build successful worker cooperatives in the absence of organizational support (Josephy). Fortunately, more and more cities are beginning to recognize and respond to the need for economic and socio-economic improvement amongst immigrant communities (Ji & Robinson). In New York City, an expanding network of cooperatives has emerged to help foster the development of cooperatives within immigrant communities.

In 2014, the New York City Council set aside $1.2 million for a Worker Cooperative Business Development Initiative (WCBDI). After achieving unprecedented success in 2015, the City Council then increased funding to $2.1 million in 2016, and $2.2 million for 2017 (Abello). According to a report released by New York City for fiscal year 2016, the WCBDI “supported 27 worker cooperatives to launch their businesses, supported business development services to a total of 49 worker cooperatives…and supported outreach to 2,164 entrepreneurs interested in converting existing businesses into worker cooperatives” (Abello). Many of the cooperatives that have received support from the city’s initiative are comprised of immigrant women of color working in highly exploitative industries, such as cleaning and child-care services (Abello). One organization that has benefited from the initiative, but which has also supported immigrant cooperative development for over a decade, is the Center for Family Life.

The Center for Family Life in Sunset Park

Sunset Park, a neighborhood located in south Brooklyn, can be described most succinctly as a “diverse, densely populated, low-income” community of immigrants from around the world (Bransburg). According to Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO), 45% of community residents immigrated to the United States from another country, 72% speak a language other than English at home, and 23% live below the poverty line. Many immigrant community members in Sunset Park have experienced the limitations that come with being an immigrant in U.S. society, such as “poverty, inadequate educational and limited employment opportunities” (Center for Family Life). Seeing a need in the community, the Center for Family Life (CFL) was established as a neighborhood social service organization in 1978, and for more than 20 years, worked to provide community members with “job readiness by helping them update their resumes, teaching job search techniques, preparing clients for interviews, enhancing computer skills, providing English as a Second Language classes, and securing interviews with potential employers” (Bransburg).

In spite of CFL’s efforts, the fact remained that many of these programs were still inaccessible to community residents, due to factors such as limited English language and computer skills, as well as precarious immigration status. In response to these challenges, “the CFL staff began to research alternatives to the traditional job readiness model” and in doing so, were able to discover examples of successful immigrant-run, worker-owned cooperatives in California, Long Island, and Staten Island (Bransburg). The CFL then decided to utilize the cooperative model within their own organization, approached unemployed and underemployed women in the community, and began the joint learning process of establishing and incubating a worker-owned cooperative enterprise. The Si Se Puede! Women’s Cleaning Cooperative was officially opened for business in 2006. Since then, “the CFL has incubated five successful cooperative businesses, together creating nearly 150 jobs for area residents” (Center for Family Life).

The cooperative incubation model utilized by CFL places emphasis on addressing the particular needs of Sunset Park’s immigrant community. One way in which this has been achieved is through the recognition and maximization of “the members’ strengths and abilities by developing types of businesses that members already have experience with such as cleaning and childcare” (Bransburg). Additionally, the CFL’s Co-op Program staff works in close proximity with developing cooperatives “for up to three years, attending meetings, assisting with office management, providing trainings, and general consultation as issues arise” (Bransburg). The success of the cooperatives fostered by the CFL in Sunset Park is indicative of the extraordinary impacts that immigrant worker cooperatives can have on individuals, families, and communities.

Spillover Effects of Cooperatives in Communities

Cooperatives offer a number of spillover effects within the communities in which they are located. With survival rates nearly twice as long as investor owned companies, cooperatives generally automate higher employment growth rates than mainstream economies (Wilson, 23). A study researching the economic impact of cooperatives estimates that within the U.S. economy, approximately 30,000 cooperatives own more than $3 trillion in assets, and generate more than $500 billion in revenue and $25 billion in wages annually (Deller et al.). The New York City Council’s WCBDI represented an “endorsement of worker cooperatives as a means of creating quality jobs and anchoring businesses in local communities” (Creating Better Jobs). They also serve as powerful mechanisms against poverty within marginalized communities.

Worker cooperatives engage with the social economy through the generation of social capital “by promoting all citizenship engagement, social cohesion and trust, and democratic processes leading to inclusion and empowerment. In addition the cooperative model can help to reduce feelings and real experiences of isolation and exclusion” (Wilson, 34). On top of hard benefits like social and financial capital, and access to meaningful work, many cooperatives also offer their members “’soft benefits, including: carpool to work, childcare, job sharing, domestic partner benefits, flex time, family leave, [and] product discounts’” (Stuart, 12).

Finally, most worker cooperatives operate with the intention of promoting equality for women, immigrants, and other groups of people underrepresented in the mainstream economy. While the reality is that marginalized groups do still experience “limited participation, particularly in areas of leadership and decision making of cooperatives,” they nevertheless possess the unique opportunity to promote structural diversity (Wilson, 26). By providing the chance for marginalized communities to engage in meaningful employment, cooperatives are able to strengthen not only their own organizations, but they are also able to help build stronger communities.

The Importance of Immigrant Worker Cooperatives in the Age of Trump

Faced with challenges unique to immigrants, such as language and cultural barriers, unrecognized foreign credentials and skills, inaccessible social services, and systemic oppression in both the workplace and society at large, finding fair and decent employment in the mainstream economy can be extremely challenging for immigrant workers. Worker cooperatives, on the other hand, “have proved to be a valuable tool for immigrant communities in meeting their social needs and in overcoming barriers to accessing social services” (Wilson, 23). Democratic workplaces offer benefits for the communities in which they are situated as well, promising social cohesion, economic and social mobility, and meaningful access to work opportunities. Organizing worker cooperatives in communities faced with specific marginalization and oppression works towards ending the cycle of societal power structures.

The incubation of worker-owned businesses in immigrant communities is often highly successful, and some research suggests that “cooperatives with a majority of members from a homogeneous cultural background have a higher chance of long-term success due to unified ideology compared to cooperatives with a more diverse membership” (Schoening). This type of success allows cooperative members to then aid in the development of the worker cooperative model in other impoverished and immigrant communities, generating strong networking opportunities.

In the next four years, these networks will serve as incredibly powerful tools under the Trump administration. Riding the wave of a campaign built upon extreme anti-immigrant sentiment and dialogue, Trump has already made good on some of his promises to crack down on immigration and undocumented citizens. On January 25, 2017, Trump signed an executive order which would increase the number of ICE agents, which already stands at more than 20,000 agents, by 10,000, sanction local law enforcement agencies with the ability to detain and arrest undocumented immigrants, and block federal funding to sanctuary cities (Ballesteros). It is unclear how many undocumented immigrants have been detained under the new order, however it was reported that nearly 700 people were detained in the first three weeks following its implementation (It’s Going Down).

Increased immigration enforcement is a direct attack on immigrant-dominated unions and workplaces (Ballesteros). With the threat of more workplace raids under the new administration, organizing efforts within hierarchical workplaces will become even more constricted than before. It is critical that in the coming years, data and support be provided to help mobilize immigrant communities, and that sanctuary cities and workplaces be developed, expanded upon, and defended.

Now more than ever before, it is imperative that we reevaluate our resistance strategies, and make a shift away from tactics that merely work within structures of domination, oppression, and exploitation, and towards a more prefigurative future, or rather, a ‘politics of the act.’ Developing framework centered around a politics of the act entails “breaking the cycle of demand and desire by ‘inventing a response that precludes the necessity of the demand’” (Wilson, 37).

Immigrant worker cooperatives embody this politics through the provision of alternative spaces of work, which in turn provide workers with an exit strategy from precarious employment relations, as well as a community and sanctuary for those within the workplace who are undocumented. Collective ownership within immigrant communities offers networks of empowerment, which are catalyzed by the desire and ability for immigrant workers to contribute to each other’s ongoing growth and protection.

Sources

Abello, O. P. (2017, January 19). NYC’s Worker Cooperative Ecosystem Continues to Grow.

Ballesteros, C. (2017, February 22). Attacks on Immigrants Are Attacks on Workers. In These Times.

Bransburg, V. (2011). The Center for Family Life: Tackling Poverty and Social Isolation in Brooklyn with Worker Cooperatives. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter, Volume 2, Issue 8.

Community Wealth. (2015, June 09). Center for Family Life. CommunityWealth.org

Democracy at Work Institute (2014). Creating Better Jobs and a Fairer Economy with Worker Cooperatives (pp. 1-7, Rep.). Oakland, CA: Democracy at Work Institute.

Deller, S., Hoyt, A., Hueth, B., & Sundaram-Stukel, R. (2009). Research on the Economic Impact of Cooperatives (pp. 1-76, Rep.). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Center for Cooperatives.

It’s Going Down. (2017, February 18). What Would It Take to Stop the Ice Raids? ItsGoingDown.org.

Johnson, M. (2010). A Network of Cooperatives Gets Organized in New York City: Low-income and immigrant workers well-represented. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter, Volume II, Issue 5.

Josephy, M. (2013). The Cooperative Fund of New England. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter, Volume 2, Issue 15.

New York City Worker Cooperative Business Development Initiative: FY16 (pp. 1-15, Rep.). (2016). New York, NY: NYC Department of Small Business Services.

Schoening, Joel (2006). “Cooperative Entrepreneurialism: Reconciling Democratic Values with Business Demands at a worker-owned firm.” Worker Participation: Current Research and Future Trends, Research in the Sociology of Work.

Schutt, R. (n.d.). Notes on Consensus Decision-Making [PDF]. Cleveland, OH.

Shifley, Rick (2003). The Organization of Work as a Factor in Social Well-Being. Contemporary Justice Review 6(2), 105-125.

Stuart, Cynthia (2003). In Word and Deed: A Social/Economic Analysis of Ontario Worker Coops. Ontario Worker Coop Federation.

Vogel, R. D. (2006). Harder Times: Undocumented Workers and the U.S. Informal Economy. Monthly Review, 58(3). doi:10.14452/mr-058-03-2006-07_4

United States Federation of Worker Cooperatives. What Is a Worker Cooperative? (pp. 1-2, Rep.). (2007). United States Federation of Worker Cooperatives.

Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing. (2017). About the Informal Economy. Wiego.org.

Wilson, A. (2008). Co-opting Precariousness: Can Worker Cooperatives be alternatives to precarious employment for marginalized populations? A case study of immigrant and refugee worker cooperatives in Canada (Master’s thesis, McMaster University, 2008) (pp. V-68). Hamilton, ON: McMaster University.