Franz Carroll

Since January 1, 2017, people across Mexico have been mobilizing in resistance to the privatization and price liberalization of the oil industry. Protesters have occupied gas stations and shut down highways for days at a time. This is all in response to what is known as “Gasolinazo”: hikes in gas prices resulting from de-subsidizing gas and the broader movement towards neoliberal policies and denationalization of industries.

From Private to Public to Private

The Mexican oil industry has been run by the state-owned company Petróleos Mexicano – known as Pemex – since 1938 – when President Lázaro Cárdenas expropriated foreign companies from the U.S., Britain and the Netherlands through a constitutional amendment (Estevez). Since then, Pemex has controlled Mexico’s oil production, exports and imports (Telesur 2016). The Mexican government, in addition to publicly controlling the means of producing oil, has subsidized its cost for consumption. These subsidies have translated to affordable prices at the gas pump for the Mexican people, many of whom make less than minimum wage (Woody).

This nationalization of the oil industry, along with other protectionist policies implemented during this era, helped Mexico replace much of its imports with domestically manufactured goods. In addition to nationalization of industries these policies included subsidies, progressive taxes, and high tariffs. These import-substitution policies resulted in a period of economic growth, known as “The Mexican Miracle,” which coincided with the post-World War II “golden age of capitalism” in the U.S. This all changed in the 1980s, when the Iranian Revolution resulted in an decreased price of oil on the global market. Mexico then had a balance of trade deficit and went into debt, so instituted austerity policies and desubsidized key industries (Solis).

Constitutional reform

Ever since the late 1970s and the dawn of the neoliberal era, reprivatizing Pemex has been a goal of proponents of free market capitalism – including North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) negotiators, the World Bank, Woodrow Wilson Center’s Mexico Institute (funded by the U.S. State Department), and the Mexican Business Association, or Coparmex (Carlsen). According to documents revealed by WikiLeaks in 2015, Hillary Clinton’s U.S. State Department heavily supported and promoted the shift towards oil privatization in Mexico (Telesur 2016). Current Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto finally proposed the reform in summer 2013 as a part of a larger reform agenda (Estevez). Peña Nieto promised this reform would “generate more energy, more cheaply for all Mexicans” (Carlsen). As of early 2017, it is looking like the reform has done the exact opposite.

Both of the dominant parties, President Peña Nieto’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and the National Action Party (PAN) supported the reform and it passed in Congress on December 10, 2013 despite opposition from the left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) (Estevez). In May 2014, a second package of legislation submitted to Congress by President Peña Nieto passed. The legislation established the rules and procedures that would dictate how this new system would work (Carlsen).

The way it works

The legislation permits Pemex to sign profit-sharing contracts, production-sharing contracts, and licenses with private companies (Estevez). Profit- and production-sharing contracts allow for the private company to aid in extraction in exchange for a cut of the profit or oil production, respectively. Licenses, according to Forbes, are little more than a euphemism for concession. Through these contracts, private companies will pay royalties to Mexico’s Central Bank in order to have full control of the oil at the wellhead (Estevez). According to Enrique Ochoa, the Deputy Energy Minister, “Companies will be allowed to register the economic interests of the risk-sharing contracts … that allow converting that value into volume while the state maintains full ownership” (Carlsen). In November 2016, multinational oil corporations, including ExxonMobil and Chevron, were able to bid on the rights to oil and gas exploration in Mexico for the first time (Di Carli). These gradual privatization efforts were likely used to prevent initial public dissent and protest.

Effects of privatization

The ruling PRI initially predicted in 2014 that these reforms would result in lower gas prices within two years, 2.5 million new jobs over 10 years, and an increase in GDP of one percent by 2018 (Carlsen). Privatization opponents in the PRD, on the other hand, predicted that the reforms would “undermine Mexico’s sovereignty” and hurt the national economy (Estevez).

Initial speculation

As early as 2014, Huffington Post and other news sources were questioning the Mexican government’s claim that this privatization scheme would reduce corruption (Carlsen). Some of the companies that were slated to take advantage of the reforms when they went into effect were Shell, Chevron, ExxonMobil Corp., and Repsol SA (Spinetto & Case). Shell specifically was sued by Pemex for being involved in a scheme to illegally smuggle oil out of Mexico, and the other three companies have disappointing social and environmental records as well (Carlsen). Even Oceanografia, a private company that Pemex already subcontracts to, was investigated for fraud in 2014 (Carlsen). These instances show that private sector is not immune to fraud or illegal activities, and these illicit actions are not limited to government officials and public employees.

Another early speculation was that oil privatization would not be as financially beneficial to the Mexican people as claimed. Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas,a Mexican politician who is a son of the president who originally nationalized Mexico’s oil, criticized the privatization on the basis that fossil fuels are nonrenewable and the Mexican reserve will eventually run out. He asked, “Where is the rational policy for managing reserves that give security to the country in the long term for a resource that is finite…?” (Carlsen). Mexico should be working towards reducing its dependency on fossil fuels, rather than banking on the privatization of its oil industry to stimulate its economy. It is a short-sighted and temporary solution, only guaranteed to help the already rich and powerful. It is more likely than not, if the scheme is successful at generating revenue, that only ones to benefit will be the already wealthy elites of Mexico and giant multinational corporations and not the general Mexican population (Solis).

Gasolinazo price liberalization

By far the largest impact from the increased privatization of Mexico’s oil has been the price liberalization and resulting price hikes. Price liberalization is a process by which, through reducing government involvement in an industry, the price of a commodity is allowed to return to its market value. But people in Mexico were reliant on the government subsidized reduced price of oil. It allowed a populace with drastic wealth inequality and high rates of poverty to be able to afford everything from fuel and electricity to basic necessities like food.

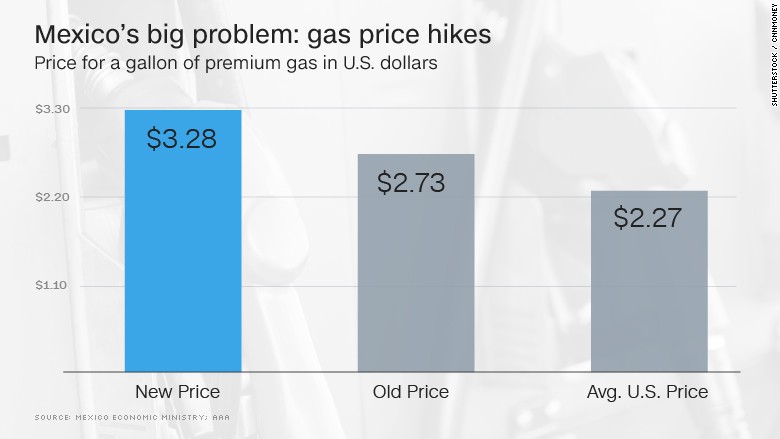

On December 27, 2016 the Finance Ministry announced that starting January 1, 2017 the price of gas would be increased by between 14% and 20% for the month of January (Woody). As a result, gas stations across the country were mobbed by consumers trying to buy up the last of the gas they would be able to get at the lower, subsidized prices (Woody). After January 1, there was an increase in oil thefts, supposedly carried out by drug cartels trying to make a profit selling it at a lower cost on the black market (Solis). Because of the price hikes, it now costs Mexicans the equivalent of 12 days of minimum-wage labor to fill a single tank of gas – this is compared to the average seven hours of minimum-wage labor in the U.S. necessary to afford a tank of gas (Solis).

On January 10, the Mexican Employers’ Association, Coparmex, asked for the price hikes to be temporarily be put on hold because of how they were affecting business. They requested that “meaningful budget cuts” be made instead (Garcia). The government rejected this request, saying that price liberalization was necessary for the government to continue to afford social programs without raising taxes (Garcia, Woody). And in the Age of Austerity, raising taxes – especially on the wealthy or on businesses – is politically unheard of, but whether this addition funding will actually go towards social spending is yet to be seen.

Resistance

Responding to calls on social media and earlier scattered protests, Mexicans across the country took to the streets on January 1 – the 23rd anniversary of the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas – to resist the Gasolinazo (Woody). Diverse groups of people participated in these demonstrations, including transportation workers, students, social workers, union members, farmworkers, activists, and politicians.

Transportation Workers

Uber and taxi drivers were another group hit particularly hard by the Gasolinazo. These workers, both unionized and not, were some of the driving force behind protests in the states of Puebla, Veracruz, Guerrero, and Michoacán, where gas shortages had made it difficult for them to work and earn a living (Woody). These transportation workers were joined by social workers in Puebla and students in Michoacán. In Guerrero and Michoacán, blockades forced almost 100 gas stations to shut down (Woody). This protest tactic is effective at hitting the oil industry where it hurts and garnering attention for the cause.

Blockades, shut-downs, and occupations

Protests across 28 of the 32 Mexican states and in the Distrito Federal (Mexico City) lasted two weeks straight, and in some cases more. These protests have included blockades of major roads, shut-downs of gas stations, occupations of government buildings. In those two weeks, more than 2,000 people were arrested – primarily for property damage – and at least six died and many more injured (Garcia, Pichardo). By the third day of protests, Pemex issued a statement that in at least three different states, protesters blockading oil terminals had led to a “critical situation” (Alper & Diaz). Despite all the attempts by government forces, they have been largely ineffective at pacifying the resistance.

Some of the largest turnouts were in the capital, Mexico City. Hundreds marched through the streets and blocked road access to surrounding neighborhoods (Woody). They chanted and carried signs that read “No al Gasolinazo” (No to Gasolinazo) and “Fuera Peña” (Peña Nieto Out). In total, over 23 stores were looted and 27 blockades built, according to the mayor of Mexico City, Miguel Angel Mancera (Okeowo). Demonstrators occupied major toll highways and allowed drivers to cross into the State of México for free for the first three weekends of January (Pichardo, Okeowo).

In Chihuahua, a Mexican state which borders the U.S., protesters blocked a rail line and oil pipelines to shut down a Pemex gas station on January 2 (Woody). Twelve days later in the same state, farmworkers occupied municipal governments and forced them to be evacuated (Pichardo). In Jalisco, masked protesters confronted police forces directly, armed with stones and bottles. They were met with the full force of riot police, who dispersed the protesters using tear gas and pepper spray (Woody). These are just some of the many examples of direct action taken against across Mexico in the first weeks of January.

Electoral politics

The Gasolinazo and resulting protests have had a devastating effect on President Peña Nieto and his government’s popularity. His approval rating reached an all-time low for modern Mexican presidents, at a dismal 12% (Solis, Agren).

Various political parties and affiliations have attempted to seize the opportunity to capitalize on the Mexican people’s anger and discontent at the current government, and redirect it to serve their own interests. The New Yorker observed that this has led to a discord of leadership within the movement, as each group has “its own distinct interests” – and the people are noticing (Okeowo). Other parties both left and right were quick to distance themselves from this unpopular government. President Peña Nieto received criticisms from the leftist PRD as well as the conservative PAN, both claiming that their own parties would not be responsible for any resulting social instability or inflation. A PRD leader even went as far as to call for a “peaceful revolution” against “a lying, treacherous government” (Woody).

There have also been attempts by smaller left-wing parties to absorb the movement base into their own membership to increase their own party’s size and influence. Andrés Manuel López Obrador – a two-time presidential candidate who recently formed his own left-wing party National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) – sought to show his party’s support for the protests and to gain popularity for the 2018 election by showing up to protest in his state of Veracruz (Woody). The Mexican Socialist Workers Party (POS) also released a statement in January praising those who came out resist the Gasolinazo:

“Partido Obrero Socialista (POS) salutes all the men and women who have come out to protest against the increase in the price of gasoline and other energy products. You are currently the most conscious segment of our population. In addition, the hundreds of thousands of people who have taken to the streets throughout the country are being slandered as looters and thieves, a campaign promoted by the government, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), and the media” (Freedom Socialist Party).

While it is noble for these parties to be speaking out for those putting themselves at risk to resist the current government, it is yet to be seen if they will fight alongside the people for meaningful solutions, or if they will just accept their votes and be done with it. Either way, it is likely that the Gasolinazo will influence the presidential election in July 2018. López Obrador, known widely as “AMLO,” is leading in the polls and this may finally be his chance at winning the office of president (Telesur, 2015).

Vibra México

Concurrent to the Gasolinazo resistance, there has been another movement brewing called Vibra México (roughly meaning “Mexico Moves”). On February 11, 2017, an estimated 11,000 people took to the streets in Mexico City to condemn U.S. President Donald Trump’s treatment and depictions of Mexico (Agren). The march itself was peaceful and featured leadership and participation from over 70 social and political organizations including civic groups, universities, NGOs and businesses (Agren, Vélez). Already Mexico has been seeing the negative effects of a Trump presidency. Right after Trump’s election, the Mexican peso dropped 12% in value against the U.S. dollar and another 2.5% after he took office (Solis). This depreciation of the Mexican peso is supposedly in response to Trump’s protectionist rhetoric that could greatly harm Mexico’s trade relationship with the U.S. For example, Ford Motors has cancelled its plans for a new plant in Mexico in favor of investing further into existing infrastructure in the U.S. (Romero)

People attended the rally to protest Trump, carrying signs that read “Stop Trump!,” but there was also anger directed towards President Peña Nieto, with signs reading “Fuera Peña!” (Grant). This is after a controversial meeting between Peña Nieto and Trump – who was then campaigning – was cancelled due to controversy over who would pay for “the wall” (Diaz). This anger directed towards Peña Nieto was quite a polarizing element at the march. Mexican historian Enrique Krauze said about the anti-Peña Nieto sentiment at the march, “Don’t forget: Mexico lost the war of 1847 and half its territory due to all the internal divisions” (Agren). Organizers of the event called for the march to be a sign of national unity in the face of a hostile foreign leader (Grant). Despite this, many rejected the rhetoric, questioning whether the calls for unity were genuine, or just unnecessary demands for nationalism and support for a “lesser evil.”

Alejandro Vélez, a Mexican professor of political science said, “The only thing that worries me is whether this type of march will not in fact sidestep and stifle the indignation and rage that has been piling up at … the incommensurable social cost of ten years of war and decades of poverty, exclusion and inequality” (Vélez). The concerns that the anger towards the Mexican government about the Gasolinazo, among other issues, will be co-opted and directed instead towards a toothless, nationalist program primarily in opposition to Donald Trump is legitimate, and needs to be countered, not through forced and artificial unity, but through mutual struggle and coalition building.

Resilience

Since the start of the Gasolinazo protests and the Vibra México march, there has been a great deal of analysis of the lasting effects of these protests, and whether this moment of resistance can be transformed into a movement for resilience. Law professor Luis Gómez Romero questions whether the final result will be a “zero-degree protest” – violent action without concrete goals or demands – or the start of a “Mexican Spring” (Romero). It may be too early to know, but there are other movements we can look towards to compare this one to to predict its trajectory. Parallels can be drawn between the resistance movement happening currently in Mexico to the movement that happened recently in Nigeria. In 2012, the Nigerian government also removed its fuel subsidies, but, in response to a mass movement of tens of thousands of people, the decision was reversed (Okeowo). There have been a multitude of other social movements across the globe that those resisting the Gasolinazo can learn from – adopting the successful tactics and being conscious of the mistakes. These include the Occupy movement, the Arab Spring, Black Lives Matter, European anti-austerity protests, and more (Vélez). The Mexican government has shown it is unwilling and incapable of providing for the economic and material well-being of its citizens, making it necessary for the Mexican people to take matters into their own hands by learning from other movements and further developing and expanding their own, already existing culture of resistance.

Various existing unions and organizations need to form coalitions and work together to mobilize different sects of the Mexican population to work together cooperatively. The National Teachers’ Union (CNTE) has a history of mobilizing both teachers and community members. The National Indigenous Caucus (CNI) movement mobilized against drug cartels and the 2014 Ayotzinapa student massacre. The Zapatistas also have the capacity to organize students and workers. Working together these groups have the potential to rally the people and transform this moment into a lasting movement.

Sources

Agren, D. (2017, February 12). Mexicans march to protest Trump — but also their own leaders and politicians. Washington Post.

Alper, A. & Diaz, L. (2017, January). Mexico gas price hike spurs looting, blockades as unrest spreads. Reuters.

BBC Business. (2014, August 7). Mexico approves oil sector reforms. BBC News.

Carlsen, L. (2014, May 29). Mexico’s oil privatization: Risky business. Huffington Post.

Diaz, D. (2017, January 25). Mexican president cancels meeting with Trump. CNN.

Di Carli, G. (2016, December 28). Export-Import Bank gave $8.5bn to Mexico oil firm despite deadly accidents. Guardian U.S.

Estevez, D. (2013, December 11). Mexico reverses history and allows private capital into lucrative oil industry. Forbes.

Freedom Socialist Party. (2017, January). To defeat the Gasolinazo. Freedom Socialist Party.

Garcia, D. & Diaz, L. (2017, January 10). Mexico’s Pemex says protests cause ‘critical’ border city fuel shortage. Reuters.

Gillespie, P. & Charner, F. (2017, February 8). Mexico’s biggest fear right now is not Donald Trump, it’s gas prices. CNN.

Grant, W. (2017, February 23). Mexico anger ahead of Tillerson visit. BBC News.

Okeowo, A. (2017. January 24). The gas price protests gripping Mexico. The New Yorker.

Pichardo, G. (2017, January 14). Gasolinazo 2017 – Mexico rises up against oil tycoons, right-wing government. Liberation News.

Rivera, H. A. (2017, January 10). Peña Nieto adds fuel to the fire in Mexico. Socialist Worker.

Romero, L. G. (2017, January 18). In Mexico, gas prices spark revolts. U.S. News & World Report.

Roos, D. (2017, February 22). Billionaire Carlos Slim Is Building Mexican-Made Electric Cars. Seeker.

Solis, J. (2017, January 7). Gasolinazo 2017: Mexican gas crisis. In Loco Politico.

Spinetto, J.P. & Case, B. (2014, January 26). Pemex CEO Sees First Production Ventures as Early as This Year. Bloomberg.

Stargardter, G. (2017, February 23). Mexico presidential frontrunner might halt new energy contracts: adviser. Reuters.

Telesur. (2015, August 3). Leftist Leader Lopez Obrador Tops Polls for 2018 Mexican Race. Telesur English.

Telesur. (2016, December 23). After privatizing its oil, Mexico becomes net importer of US fuel. Telesur English.

Vélez, A. (2017, February 14). From the Gasolinazo to Vibra México: the trivialization of resentment. OpenDemocracy.

Woody, C. (2017, January 3). ‘We are going to remember it at the polls’: Outcry about fuel price hikes may be trouble for Mexico’s government. Business Insider.