Rebecca Bramwell

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and hundreds of thousands of Indigenous supporters from around the world been fighting against the Dakota Access Pipeline since the summer of 2015 in North Dakota. The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) is a $3.7 billion project intended to move crude oil from the Bakken oil fracking field in North Dakota to Illinois, and the proposed route of the pipeline crosses the Missouri River just north of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. Simply getting the public to recognize the reality of this issue has been a long battle, especially as the Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) has continued to move forward with construction of DAPL, and corporate control of our politicians and major media has covered up much of the truth. However, with a huge influx of social media awareness, Standing Rock has gained massive support from around the world, building vital and unprecedented alliances in what is surely the most powerful Indigenous resistance and resilience movement in the U.S. in recent years, a movement which continues to change by the minute.

The Problem with Pipelines

Something that is important to establish from the very beginning is that Standing Rock is an outcry to an ongoing problem that has been dramatically affecting people’s lives for decades. There are an estimated 2.5 million miles of pipelines in the United States, and every day more projects are being proposed. Statistics show that as oil production increases, so have pipeline spills. “Since 2009, the annual number of significant accidents on oil and petroleum pipelines has shot up by almost 60 percent, roughly matching the rise in U.S. crude oil production, according an analysis of federal data by the Associated Press” (Chicago Tribune).

While there is some debate about exactly why so many ruptures are occurring, these incidents in large part have to do with age, infrastructure, and regulation. More than 50% of the pipelines in the U.S. are at least 50 years old. As pipelines age and are exposed to the elements, they are more likely to leak. Corrosion has caused between 15-20% of all reported significant incidents (ProPublica). An ABC news video documents the second pipeline explosion in two months on the Colonial Pipeline.

A major focus of the pipeline policy battle is inconsistent or inadequate regulations, testing, and follow through. ProPublica explains that operators often use a risk-based system to maintain their pipelines. Instead of treating all pipelines equally, they focus safety efforts on the lines deemed most risky, and those that would cause the most harm if they failed. The issue with this approach is that each company uses different criteria, which Carl Weimer, executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust says is “a nightmare for regulators” (Chicago Tribune).

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) is criticized for not having the funding or resources to properly maintain the millions of miles of pipelines over which it has authority. The agency is known for being understaffed and is chronically short of inspectors because it just does not have enough money to hire more, possibly due to competition from the pipeline companies themselves, who often hire away PHMSA inspectors for their corporate safety programs (ProPublica).

Like many other commercial industries, the limitations of government money and personnel means the industry itself often inspects its own pipelines. Pipeline operators relationship with PHMSA most likely goes beyond this, as the agency has to date adopted dozens of safety standards written by the oil and natural gas industry. “This isn’t like the fox guarding the hen house,” said Weimer. “It’s like the fox designing the hen house” (ProPublica).

This video from January 2015 goes into detail about several major oil spills and natural gas pipeline ruptures in the U.S. that took place in the span of just a few weeks.

At What Price?

Since 1986, pipeline accidents have cost nearly seven billion dollars total, in property damages alone. ProPublica has mapped thousands of pipelines incidents in a new interactive news application, which provides detailed information using government data about the cause and costs of reported incidents. This beneficial tool can connect people with incidents that are near their community, as well as find similar incidents to help build public cases against pipelines and the companies that constructed them. Additionally, it is a wakeup call for just how often these breeches are happening and the reality of our nation’s unnecessary reliance on pipelines at a rising cost (ProPublica).

Money is not the only issue here. When pipelines rupture, they result in hundreds of thousands of gallons of crude oil leaking into lakes, rivers, infiltrating groundwater, and killing more than 500 people and injured more than 4,000, just in the past three decades. These figures unfortunately only account for direct fatalities and costs, but do not acknowledge the environmental damages and effects. Oil spills can cause a variety of ecological issues, specifically due to physical smothering of organisms, chemical toxicity, ecological changes that are caused by loss of key species that perform functions in an ecosystem, and other indirect effects from loss of shelter and habitat. These ecological issues directly effect human populations, towns, cities, counties, and watersheds, especially low-income and subsistence cultures, a prime example being Indigenous communities (ITOPF).

History

Government policies toward Native Americans as a whole have reflected one theme: control and exploitation of Indigenous assets. Although different tribes have slightly different circumstances of treaties and settlement, the U.S. has thrived on methodically removing wealth from Native populations – the more value we recognize in Native lands and resources, the more we collectively strip away their sovereignty and disempower them. In The Color of Wealth, the long series of legislation is discussed in depth, but the strong thread that that continues to emerge in these laws is the conflict between Native American value systems and Western concepts of property rights. The land, often considered sacred by the Indigenous nations, was increasingly commodified and sold for profit to benefit white settlers, a process which is far from over and in fact happening right in front of us today (Lui).

Similar to the race for land and industrial growth in the late 1700s and early 1800s, Big Oil and pipeline operators are seizing an opportunity to make big bucks off riskier and riskier practices of exploiting, and now transporting, natural resources. There are countless examples of Native communities that disproportionally suffered during the Gold Rush, previous oil booms, and the mining craze, they are to this day combating the environmental implications of white industrialization. A key worry for many, especially in regards to pipelines, is knowing that most of the infrastructure is a ticking time bomb. Joe Mendelson, one of the National Wildlife Federation’s directors, describes pipelines as “inherently dangerous.” We cannot deny the environmental and financial implications already in play with other pipelines, as even the preemptive work being done to maximize safety are clearly part of the same flawed corporate system, yet here we are, at the crossroads with yet another proposed line. In the case of the Dakota Access Pipeline, however, the Standing Rock Sioux have not stood by in silence, and the world is taking note.

Water is Life

One of the loudest and best known rallying cries coming from the Standing Rock resistance has been “Mni Wiconi,” meaning Water is Life. This message and sentiment from Standing Rock and earlier movements has been spreading across the country and the world like wildfire.

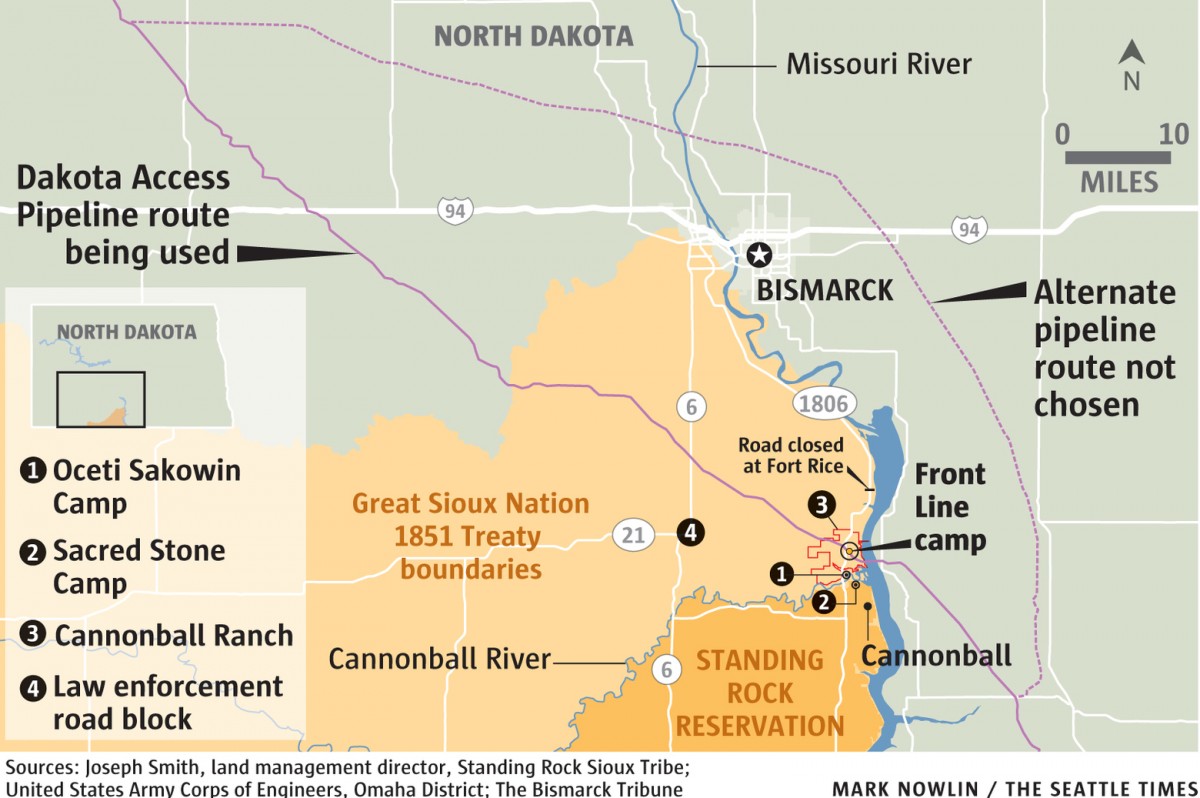

The Dakota Access Pipeline is a $3.8 billion dollar project that began construction in March 2016. The pipeline would reach 1,172 miles in length and most importantly would cross the Missouri River just north of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. The threat of an oil spill in their river, which would pollute the main water source for the Sioux, has led to mass actions to stop the pipeline through legal channels and direct action. While the pipeline technically does not go through the reservation itself, it does cross 1851 and 1868 treaty territory and sacred burial grounds. Indian land has been incrementally reduced over time to limit Indigenous communities’ control over their precious resources. This project and the processes involved represent a symbolic confrontation, The New York Times reporting:

“The confrontation cannot help summoning a wretched history. Not far from Standing Rock, in the Black Hills of South Dakota, sacred land was stolen from the Sioux, plundered for gold and other minerals, and then carved into four monumental presidential heads: an American shrine built from a brazen act of defacement.

The Sioux know as well as any of America’s native peoples that justice is a shifting concept, that treaties, laws and promises can wilt under the implacable pressure for mineral extraction. But without relitigating the history of the North American conquest, perhaps the protesters can achieve their aim to stop or reroute the pipeline” (The Editorial Board).

What is especially powerful about this resistance is the reclaiming of Indigenous value systems as a rallying point for challenging historic settler property rights and commodification of sacred land and water. Colonization has been the long standing root of conflict since the beginning of U.S. history, and the water protectors of Standing Rock are reminding all of us that they are not going anywhere.

The Start of Action

DAPL construction began in March 2016 after receiving a construction permit from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, and immediately the Standing Rock Sioux voiced concerns about environmental impacts, requesting an environmental impact survey to be done as early as March and April, due to a lack of federal-tribal consultation. By May, DAPL was already receiving temporary halt orders as the pipeline was disrupting historic and cultural land sites and disrupting agricultural land in Iowa (Petrowski).

Water Protectors have been involved from beginning; their first camp emerged in April when members of the Standing Rock Sioux and other tribes rode on horseback and established a spiritual camp called Sacred Stone. In addition, as various parts of the pipeline began to be constructed and with rising tensions leading into the summer, nearly 33,000 petitions were sent in to the U.S. Department of Justice in July 2016 to review permits (Leland).

Several other large camps have formed since then, many of them becoming a new home and symbol of hope to both Native and non-Native opponents of the pipeline. The main camp where up to several thousand were gathered is called Oceti Sakowin (Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota Sioux). The Standing Rock camps are all located about an hour south of Bismarck, North Dakota.

Camp Basics

The three major camps at Standing Rock were the Oceti Sakowin, Sacred Stone, and Red Warrior. These all served various purposes in the building of community, as people from around the world arrived. The majority of people resided in Oceti Sakowin, where food and other donations were accepted and many services were offered to people. There was a large area designated to cooking and feeding people, sometimes up to thousands of them, water tents, orientation tents, aid tents, legal tents, charging stations, council and elder tents, and more (The National).

A common misconception about Standing Rock was that it was all about resistance and direct action. Simply living on treaty land was a form of action. There were in many cases confrontations with law enforcement, but most of the work was about revitalizing Indigenous community. Much of this work of resilience has been organized by Indigenous women, who have continually put their bodies on the line and acted as some of the most fierce water protectors. A welcome crew at the gates informed anyone coming into the camp of the rules and expectations, helped to move in and store donations, and directed people to where they needed to be. A key responsibility was cooking and cleaning, which required continuous work. Many people who were good at directing or had carpentry skills began to expand the camp and build new structures, winterproof existing structures, and more. More than anything, this camp thrived off of the expectation that everyone do their part, recognize their strengths and weaknesses, and find their place in the existing structure that benefited others more than it benefited them. All of this was built upon Indigenous leadership (The National).

Unlikely Alliances

Standing Rock is a prime example of an Indigenous-focused and Indigenous-led movement. Indigenous rights as a centering force defined the camp and this caused a culmination of forces which had no existed together before. “It’s the first time the seven bands of the Great Sioux Nation have united since Custer was defeated 140 years ago, and with more than 300 nations standing in official solidarity with the movement, it is by far the largest mobilization of Indigenous peoples in the United States in a generation or more” (The Nation). A photo published in The Nation’s photo essay about Standing Rock shows the bright flags of more than 300 First Nations lining the road into the Oceti Sakowin camp. This strong leadership has laid the basis for a non-violent and spiritual resistance. The convergence of so many indigenous groups also allowed for immense healing and community growth through regular prayer and drum circles, sunrise and sunset prayer walks, and more.

Standing Rock offers North American people a lesson in resistance, also bringing together Black Lives Matter, environmentalist groups, various progressive media platforms, and even veterans. The Water is Life rallying call is not just about Indigenous communities, but recognizing that water is life, medicine, and essential to survival for all 17 million people who rely on the same water source. Pipelines are a danger to all people, and the inevitable rupture of DAPL would not just be devastating for the Standing Rock Sioux, but effect everyone downstream along the Missouri River. The selfless act of putting themselves in the way of this project, protecting water for all, and the use of spirituality and love has brought their fight to national prominence (UPROXX).

What’s Media Got to Do With It?

While the foundation of this movement has been overwhelmingly positive and built around an issue everyone has a stake in, unfortunately some media sources have not been showcasing it in a good light, if they show it at all, and that has had dangerous implications for the occupants of Standing Rock.

A common controversy seen in the reporting of Indigenous issues comes down to a fundamental profit-driven journalistic question: what is newsworthy? While this question inherently forms biases and selective coverage for all types of current events, it is especially obvious for Indigenous coverage. It is common for journalists today to reduce Indigenous people to one-dimensional characters caught between two worlds. In fact, for the press, it is a tradition because historically it has been beneficial for the U.S. to document Native communities as little as possible, a tactic to perpetuate ignorance and misunderstanding in the public, and many would argue that is still true today.

The reality of Standing Rock was that the Sioux were fighting against DAPL from the very beginning, in April 2016, but nobody really knew about it. It took until the end of July for a large influx of bloggers and citizen journalists, which started to increase the visibility on social media, but it was not until violent repression began in early September for outlets like CNN and NBC to show up. In other words, it took five months for mainstream media to actually address that a few thousand Native Americans physically resisting the construction of an oil pipeline was newsworthy. In a compelling article by award-winning journalist and member of the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma, Tristan Ahtone wrote,

“Reporting on the bureaucratic nightmare that leads to Standing Rock isn’t all that sexy. In those stories, the Indians wear suits, file a lot of paperwork and use the courts to fight for their rights. In those stories, the Indians play by government rules while the government weasels its way out of playing by any rules.

But when things finally come to a head and people take to the streets – or in this case, the plains – journalists are more than happy to return to Indian Country: that place where the modern and the ancient world clash.

The election played a big role in the press corps’ inability to see what was happening at Standing Rock, but the real reason national outlets didn’t pay attention is much simpler: They don’t care about Indians” (Ahtone).

In the rare case that media outlets were recognizing Standing Rock, many used the space to explore contradictory views within the community. An example of this is a CNN article entitled “Not all the Standing Rock Sioux are protesting the pipeline,” which spent nearly half of the article highlighting the interview of a Sioux man who felt the protests had “become a downright nuisance to his community,” talking about how it was protestors’ fault that there was conflict with police and making people drive out of their way to go around the checkpoints (Ravitz). This kind of rhetoric of everyday citizens blaming issues on the people protesting a larger issue caused by big corporations or big government is a common theme we have seen in social movements and revolutions around the world.

Another component in shaping public perception is the criminalization of protestors. As I was doing my research for this project, I did a quick Google search for DAPL, and the very first thing that came up was a website called Dakota Access Pipeline Facts. This website is entirely dedicated to providing “facts” and news pieces that discredit the cause of the Standing Rock protestors. It has pages about safety, claiming that DAPL is “safe, efficient, and environmentally sound,” pages dedicated to misconceptions such as “the majority of protesters are not there to protect water, as they claim, but are actually extremists opposed to any and all use of fossil fuels.” There is also a News and Opinion section that has known alt-right news sources slandering the protests and talking about how economically beneficial the pipeline will be to the country. The website pits the progress of the U.S. against indigenous people, just like during western expansion, and the gold rush, and the hydroelectric era, and the fishing wars.

The worst part of it all? This is a paid advertisement on Google, which is why it comes up first, and it has a direct link to the “landowners site,” Energy Transfer Partners, the company which owns this pipeline. Even the general public who cares enough to want to get information about what is going on cannot do a basic google search without having company sponsored propaganda fed to you without even realizing it. It is beneficial for our corporations and government to support this because it shifts the focus away from them and removes them of the responsibility of creating this issue in the first place, in the case of Standing Rock, once again threatening their existence by compromising their water and destroying cultural land sites.

Police Brutality

This type of divisive language that is non-contextual, factually inaccurate, and biased is problematic because it dehumanizes protestors in a time when they need protection. Luckily, social media has played a saving role in getting the truth out to the public. Standing Rock was met with aggression from the Morton County Sheriff’s office, accompanied by Cass County law enforcement and other police agencies from across the state and region that came in as support. They formed a highly militarized police force that aggressively targeted protesters attempting to block construction or simply pray. The police were often armed with tanks and riot gear, and used pepper spray, teargas, rubber bullets, Tasers, and other “less-than-lethal” weapons, even to respond to peaceful ceremonies and prayer circles (Woolf).

To date, there have been nearly 500 arrests, the majority of those taking place in one week, with 120 arrests on October 22nd and 141 people on October 27th. These incredibly tense incidents left hundreds of witnesses who all echo the same sentiments, which is that these arrests took place on peaceful protestors, many who were praying or singing, and even on journalists. Many claim to have been held in cages. In the wake of this disastrous attempt to control protestors, a United Nations group has opened an investigation into local law enforcement due to accusations of human rights violations in their treatment of jailed protestors (Levin).

Later on in the protests, in late November, police used water cannon to drench protestors in well-below-freezing weather. This was also an obvious human rights violation as it easily could have resulted in death. Nearly 200 were injured, 30 were sent to the hospital, and one protestor in particular nearly lost her arm after a concussion grenade was thrown at her point blank. When asked in a press conference about the use of water cannons, Morton County Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier said, “We don’t have water cannons” (The Intercept). Luckily, there were people doing livestream videos and the use of social media was able to document these violent attacks from police when mainstream media often did not.

Victory for Standing Rock?

A major development in the Standing Rock movement was on December 4th when the Army Corps of Engineers announced it would not be granting an easement to the Dakota Access Pipeline to cross the river, and Standing Rock erupted into celebration with large dance and prayer circles.

Many people assumed that the Army Corps of Engineers decision was the end of the battle, but after Trump took office in January, he signed an executive order reopening and advancing the approval of the DAPL as well as the Keystone XL pipeline. Many find it interesting that this one of the first few actions he took in office, especially since Trump had a financial investment in Energy Transfer Partnerss, the company behind the Dakota Access Pipeline. While he technically sold it in 2015, he still has investments in other companies that are invested in the pipeline, which is a clear conflict of interest.

With the known danger of spring flooding in the valley, the remaining water protectors at Standing Rock already had plans to pack up and head home, but in light of the executive order and the eviction notice from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, media has presented it a loss for Standing Rock. However, Lyla June, a longstanding water protector spoke passionately in her Facebook live video on February 23rd about this victory for Standing Rock. In her video she says,

“We need to counter the narrative that this movement is over or that we lost the movement because we actually won this movement in many profound ways…We are seeds and they may have buried us, but we have planted seeds all around the world and inspired people to see water in a new way, to see water as life, and we have also for that matter untied things that have never been united before. We united Christian groups with indigenous groups. We united the U.S. army with indigenous groups. We united all races in this country behind a common dream.

We fought in a manner that was so beautiful…We gave our bodies, we fought in courts, we fought financially, we have done everything in our power to protect this water and that is a win…Let’s send a really loud message to the world, that the battle didn’t end today…we won in all of the most important ways…We need to keep this thing moving forward to really send a clear message to our descendants that we stood up and we fought and we gave everything we had and we made a difference for the whole world.”

This was one of the last livestreams in the camp before the water protectors were evicted, and was powerful for many as the livestream videos had been such a vital tool for getting the truth out there in the nearly year long protest.

Standing Rock has been a symbol of hope for so many, and shown resistance against Big Oil as well as proven the resilience of indigenous value systems. Activists all over the world have been touched by this movement, and now speak fondly of taking Standing Rock home.

Sources

Board, T. E. (2016, November 3). Time to Move the Standing Rock Pipeline. The New York Times.

Brown, A. (2016, November 21). Medics Describe How Police Sprayed Standing Rock Demonstrators With Tear Gas and Water Cannons. The Intercept.

Chicago Tribune. (2015, May 22). Federal data: As oil production soars, so do pipeline leaks. Chicago Tribune.

Dakota Access Pipeline Facts. (n.d.). Dakota Access Pipeline Facts

Dennis, B. (2016, December 5) Army Corps ruling is a big win for foes of Dakota Access Pipeline. Washington Post.

Dreyfuss, E. (n.d.). Social Media Made the World Care About Standing Rock—And Helped It Forget. Wired.

Energy Transfer Partners (n.d.). ETP

Erbentraut, J. Here’s What You Need To Know About The Dakota Pipeline Protest. Huffington Post.

Groeger, L. (2012, November 15). Pipelines Explained: How Safe are America’s 2.5 Million Miles of Pipelines? ProPublica.

Hawkins, D. (2016, November 21) Police defend use of water cannons on Dakota Access protesters in freezing weather. Washington Post.

International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation. (n.d.). Environmental Effects. ITOPF.

June, L. (2017, February 23). Victory for Standing Rock. Facebook.

Levin, S. (2016, October 25). Over 120 arrested at North Dakota pipeline protests, including journalists. The Guardian.

Levin, S. (2016, November 3). Dakota Access pipeline: the who, what and why of the Standing Rock protests. The Guardian.

Levin, S., & Woolf, N. (2016, November 3). Dakota Access pipeline: police fire rubber bullets and mace activists during water protest. The Guardian.

Lui, M., & United for a Fair Economy. (2006). The color of wealth : The story behind the U.S. racial wealth divide. New York: New Press : Distributed by W.W. Norton.

Michael Leland, Iowa Public Radio (2016, September 15). “Bakken pipeline opposition presents petitions to U.S. Justice Department”. Radio Iowa.

Petrowski, William (2016, May 27). “Tribal land issues block Bakken pipeline in Iowa”. Des Moines Register.