Zack Shaver

The Spotted Owl Wars of the 1990s, in my home state of Washington, were technically a win for the environmental movement, but it was bittersweet victory, having unexpected environmental, economic and cultural effects that are still unfolding. The conflict is being brought back into the light being as the Trump administration has similar policies towards the environment as the Bush administrations. I will include background on the logging industry west of the Cascade Mountains, particularly in old growth forest. I will discuss the success of Republicans and Democrats in the 1960s and 1970s in cooperating to create and pass environmental protections, and how those in were latter used and misused, leading to a divide between environmentalists and the working class. I will also describe some partnerships and alliances that have resulted from the Spotted Owl Wars and what we might expect to see over the next four years.

Old Growth Forest in the Pacific Northwest

It is estimated that before industrial logging came to the Pacific Northwest, there were more than 17 million acres of old growth forest and the estimates of what remains is between three and seven percent (Blumenthal). There are no exact numbers on how much old growth exists or how much there was in the past, because the term old growth is a bit problematic. The term “old growth” was coined by forestry scientists but it was defined in general terms.

“Old growth is not simply synonymous with virgin forest, or forest that has never been cut. Not all uncut forest land is old growth–fire, wind and terrain ensured that only about 60 or 70 percent of the virgin forest pioneers found would meet the biological definition–and it is possible for regrown forest to develop into old growth given enough time. In fact, there was no scientific consensus on what old growth even was: how big the trees had to be, and how many, and what kind and shape, and how many snags and logs” (Dietrich).

The undefined nature of the term old growth led the Oregon Natural Resources Council to try to strategize on a new term for old growth. The term ‘primeval forest’ was suggested (Dietrich) but was rejected because it contains the word “evil.” The organization settled on the term ‘ancient forest’ instead. This term is also technically inaccurate because the common Eurocentric definition of the word ancient means that something is from before the fall of the Roman Empire, even though there are (or were) California redwoods that are that old. The council selected this term for the forest because it was ‘snappier’ and more appealing to the public, they thought the term ‘old growth’ would not be attractive to our youth-worshipping society (Dietrich).

The general agreed-upon, most basic definition for old growth–also known as Primary Forest, Primeval Forest, Virgin Forest, Late Seral Forest or Ancient Forest–is a forest that has reached a significant age without any significant disturbances and as a result displays unique ecological features. Old growth as far as the Pacific Northwest is concerned (the definition varies from region to region) generally contain large trees as well as many dead standing trees. Old growth forest is usually very biologically diverse, as well as diverse in the age of other species that grow there which ensures its health in the long term. The dead trees that old growth forests contain are important for several reasons; they create openings in the canopy as well as leave snags (dead trees) and materials to decay and decompose on the forest floor to provide nutrients for other growth (White).

History of Logging in the Pacific Northwest

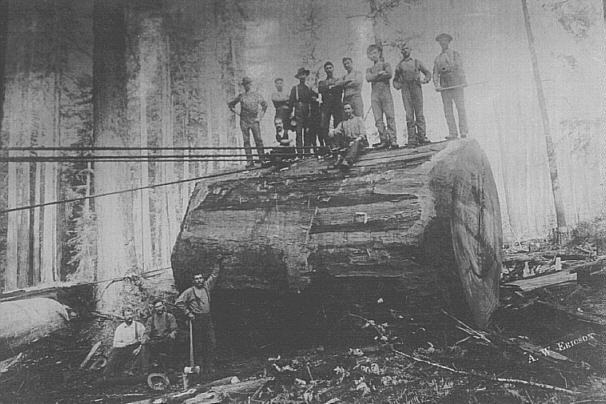

The woods of the Pacific Northwest, from northern California up through western Washington, have been consistently being logged since the arrival of the first white settlers to the area. Indigenous peoples of these areas have been utilizing the timber in the woods for everything from homes to boats to clothes for more than a thousand years, but there are not any circumstances where there was any kind of large-scale tree logging (Gonzalez). The closest thing to clear-cutting that indigenous peoples did was to burn brush and tree seedlings to create and preserve meadows for hunting and foraging (Wilkinson, 22-23).

According to the Center of the Study of the Pacific Northwest at the University of Washington, the history of logging in the Pacific Northwest can be divided into four phases or periods:

1828-1847: This period saw the start of the lumber industry in the Pacific Northwest, with the first mill established at Fort Vancouver in 1828 by the Hudson Bay Company.

1848-1882: The second phase of logging came with the California Gold Rush of 1848. Many investors from the San Francisco area built mills along the Puget Sound, establishing logging as the dominant industry in the Pacific Northwest.

1883-1940: The logging industry really exploded with massive capital investments and technological developments, allowing for high quantities of timber to be reached and processed. Also during this period came lots of influence from the government on industry and from labor unions.

1942-2017: The final phase, has seen the timber industry’s importance to the state economy steadily drop even when timber harvesting did not, and also saw the rise of the environmental movement (Chiang).

The timber industry’s employment has been steadily declining since the 1950s as automation has become more and more commonplace. The number of jobs plummeted but they became much safer. After the Great Depression, the timber industry never recovered as the largest employer in the region because in the 1940s and 1950s other industries grew in Washington, for example, Boeing aircraft manufacturing, Hanford’s nuclear waste storage, and fruit harvesting. The timber industry has always been a boom-and-bust industry headed by very aggressive business leaders. After the 1970s the increasing restrictions on where and how much timber companies could cut, caused them to go on a clear cutting frenzy in the 1980s.

History of the EPA and Federal Regulations

By the late 1960s, there were an ever increasing number of local laws and regulations around environmental protection, but no solid federal agencies existed to manage them, so Senator Henry M. Jackson (D-Everett) helped write and propose the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA). President Nixon signed the law in on January 1, 1970. To give an idea of how bipartisan and popular environmental protection was at the time, the Senate passed NEPA unanimously and 372-15 in the House. In December 1970, Nixon made the decision under NEPA to consolidate all related agencies in the government under the newly created Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Two of the most significant parts of NEPA that carried over into the EPA are the requirement of federal agencies to prepare Environmental Assessments (EAs) and Environmental Impact Statements (EISs) (Dowdy).

Some federal environmental legislation had been passed prior to the creation of the EPA but until the EPA was established those laws were poorly enforced. Part of the EPA is the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) which is a council in the White House that directly advises the President (EPA.gov).

Also, the Endangered Species Act of 1973 was passed just as unanimously in the House and Senate as NEPA was three years earlier. It was written by lawyers and scientists from the CEQ, NEPA, EPA, NOAA and the Army Corps of Engineers. The purpose of the Act is to protect species and their environments from which they depend. It is administered by NOAA and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (fws.gov).

The Spotted Owl Wars

The Spotted Owl Wars, as people involved with the situation understand, were only partially about the Spotted Owl and was really about environmental ethics versus economic interests. The Spotted Owl is what is known as an indicator species, “reflecting the health of the forests” (Blumenthal). The loss of the owl signaled that the old growth ecosystem of the Pacific Northwest was dying. The cause of this was blatantly obvious, as visitors could drive anywhere in western Washington and and see clear cuts. This is how many visitors from the Seattle area became involved, from seeing the cuts from the road when they would drive out to hike, and this perspective caused resentment from the loggers.

“Poppe considers the environmentalists a bit too self-righteous, as if they invented love for the outdoors with their weekend hikes. Well, these loggers live in the woods and work in the woods and play in the woods. They are out in the chill rain and the hot sun. They see deer while driving to the logging job in the morning and eagles on the way home. They fish, they hunt, they hike. These forests are to them a mosaic of memory a city dweller can’t imagine, a hundred places cut and regrown” (Dietrich).

It came down to some environmentalists fighting against the big logging interests, who were using their employees, the loggers, truck drivers, and mill workers to fight the environmentalists for them. The three major timber companies that the environmentalists were fighting were Georgia Pacific (G-P), Pacific Lumber (P-L), and Louisiana Pacific (L-P). In the long run, the interests of the lumber workers and the environmentalists were the same, they both want the forest to exist and resented the companies, just for different reasons.

“Why have the companies been so successful at misdirecting the workers anger? One obvious reason is fear–timber workers can see the end of the forest (and their jobs)…Many if these families have lived and worked in small one-job towns for generations. The environmentalists are often relative new comers, culturally different and easy to vilify. But there’s another reason not often discussed. That is the utter lack of class consciousness by virtually all of the environmental groups” (Bari).

The environmentalists were often guilty of looking at the lumber workers and the lumber companies as the same entity. With this mindset, it was a piece of cake for the logging companies to turn the employees against the activists. To combat this, Earth First! adopted some of the ideas that the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.). have used to bring class consciousness into their movement, which meant that the activists stopped blaming the loggers and started recognizing them as being exploited for profit, along with the forest.

Environmentalists used the legal system to get the Spotted Owl registered under the Endangered Species Act on June 26, 1990 (Boyles). This meant that after studies were conducted to determine how much vital habitat the owls needed, then restrictions were put on the logging industry and how much they could cut from federal lands. The main argument of the logging industry was that protections for the owl were destroying thousands of jobs. It is true that jobs were lost but it was nothing compared to the 90% decrease in jobs in the timber industry since World War Two because of the industry’s own actions, such as automation and export of raw logs to Asia rather than milling them at home (Dietrich).

A tactic used by an environmentalist and a former logger turned environmentalist, was they bought an old growth log and a flat bed truck and toured through 44 states with it to bring national attention to the issue, drawing a decent amount of attention (Dietrich).

“The logs thickness fascinated people. During the log’s cross-country tour, one man who clambered up on the truck to grasp the wood wouldn’t let go. Only when the truck started pulling away to re-enter the freeway did he reluctantly jump off. In two places, St. Louis and Long Island, men saw the log, quit their jobs, and moved to Oregon to work on the tree issue, eventually meeting and forming a “Save America’s Forest Coalition. At a New Jersey Turnpike rest stop, strangers walked up and wrote checks of $50 and $100 in support” (Dietrich).

Given that most worker’s understanding of the situation was that it was either the lives of a few owls or their livelihoods, they were understandably angered. In 1994, lawmakers, scientists, land managers, and industry representatives came up with the Northwest Forest Plan in hopes to end the tensions.

The goal of the Northwest Forest Plan was to allow new growth plenty of time to flourish, while also leaving enough land for the timber industry to get a certain cut every year. The environmentalists continued to work with the timber workers, making it clear that they were not putting the importance of the owl over the lives of the workers. It was the importance of an entire ecosystem that needed to be protected if the workers wanted sustained work. Clearcutting the forest too quickly would mean a quicker loss of timber jobs. Many workers also resented the companies for poor health and safety conditions, and not enough wages or benefits.

Are the Spotted Owl Wars Over?

The issue was brought back to the table during the George W. Bush administration. Bush tried to reverse the Northwest Forest Plan, but faced an outcry from scientists and environmentalists. The Bureau of Land Management was favorable toward freeing up more land for logging but it was technically illegal and was stopped by the Obama administration (Koberstein). Another factor in the future of Pacific Northwest forests is that the Spotted Owl population has still been declining and is actually dropping quite fast, at about 7.2% annually.

A major factor in this is not just that there is a period of time before populations start to stabilize and grow again but that there is an invasive species of owl, the Barred Owl, related to the Spotted Owl but it is more dominant and therefore is further hindering the recovery of the spotted owl (Welch).

The Obama administration was relatively favorable to environmental protection, or at least it was somewhat balanced and not a completely unregulated ransacking of resources. Regardless of some of his other environmental decisions, his administration backed up the Northwest Forest Plan. Now things are going to be very different under the Trump administration.

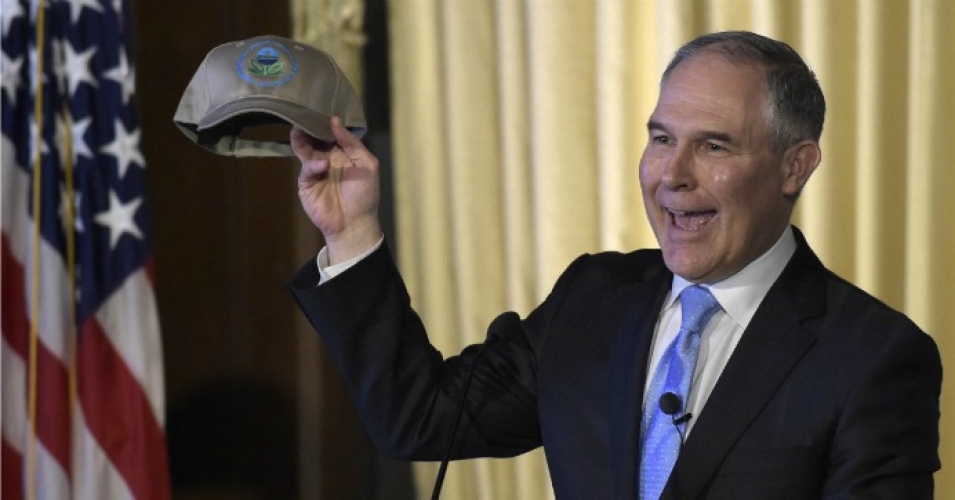

The new head of the EPA, Scott Pruitt, spent the last six years as Attorney General for the state of Oklahoma. Pruitt has been a major opponent of the EPA for his whole time as Attorney General.

“The Oklahoma Attorney General’s office on Tuesday released a batch of more than 7,500 pages of emails and other records, after a judge last week found Pruitt in violation of the state’s Open Records Act for improperly withholding public records requested by the Center for Media and Democracy (CMD). The group made the documents public on Wednesday. They show that Pruitt—who sued the EPA more than a dozen times as attorney general—”closely coordinated with major oil and gas producers, electric utilities, and political groups with ties to the libertarian billionaire brothers Charles G. and David H. Koch to roll back environmental regulations,” according to the New York Times” (Fulton).

It is very clear from the emails that were released from Pruitt’s time as Attorney General that he is very connected to the fossil fuel industry, and is very willing to fight very hard for it. Pruitt has been quoted as a climate change denier. He did not mention climate change once during his acceptance speech for the EPA directorship (Fulton).

It’s going to take much time and work for Pruitt to reverse environmental regulations set up by the Obama administration. For one, many employees of the EPA openly disagree with Pruitt and aim to make sure he sticks to adhering to science and not ideology (Dennis).

To reverse or revamp existing rules around vehicle fuel standards, mercury pollution or a range of other environmental issues, Pruitt would have to repeat the lengthy bureaucratic process that generated them. Other initiatives, such as the so-called Clean Power Plan aimed at regulating emissions from power plants, remain tied up federal courts (Dennis).

On top of this kind of legal work, many environmental groups are planning to sue Pruitt every step of the way. In addition to environmental groups and current EPA employees, many former employees are interested in challenging Pruitt’s decisions. For example more than 700 former EPA officials wrote to Congress to oppose his conformation. As we are beginning to see, there are going to be a lot of challenges to environmental protections over the next few years, but there are just as many people (if not significantly more) who are fighting to not only keep but expand protections.

Sources

Andre, C., & Velasquez, M. (2015). The Spotted Owl Controversy. Ethics and the Environment. Markkula Center for Applied Ethics.

Bari, J. (1994). Timber Wars. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press.

Blumenthal, L. (2010, September 25). After 20 years of protection, owl declining but forests remain. McClatchy DC Bureau

Boyles, K. (2010, June 24). 20th Anniversary Northern Spotted Owl Listed As Threatened Species June 26, 2010. Earthjustice.

Buchanan, J. B. (2016). Periodic Status Review for the Northern Spotted Owl in Washington. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Program. Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Chiang, C. Y. (n.d.). Evergreen State: Exploring the History of Washington’s Forests. Center for the Study of Pacific Northwest.

Daley, J. (2016). The Burning Questions About Spotted Owls and Fire. Sierra Club. Sierra Club.

Dennis, B. (2017, February 17). Scott Pruitt, longtime adversary of EPA, confirmed to lead the agency. The Washington Post.

Dietrich, W. (1993). The Final Forest : The Battle for the Last Great Trees of the Pacific Northwest. New York: Penguin Books.

Dowdy, S. (2007, November 08). How the EPA Works. How Stuff Works.

Durbin, K. (1998). Tree Huggers : Victory, Defeat & Renewal in the Northwest Ancient Forest Campaign. Seattle: Mountaineers.

EPA History. (2016, December 21). EPA.

Fulton, D. (2017, February 22). Email Dump Reveals EPA Chief Pruitt’s Cozy Ties With Fossil Fuels Industry. Common Dreams.

Gonzalez, Josefina S. (2004). Growth, Properties and Uses of Western Red Cedar (Thuja Plicata Donn Ex D. Don). Vancouver BC: Forintek Canada.

Koberstein, P. (2015, April 07). Will the Northwest Forest Plan come undone? High Country News.

Loomis, E., & Edgington, R. (2012). Lives Under the Canopy: Spotted Owls and Loggers in Western Forests. Natural Resources Journal, 52.

Luoma, J. (2006). The Hidden Forest. Corvallis, OR : Oregon State University Press.

Rose, F. (2000). Coalitions Across the Class Divide : Lessons from the Labor, Peace, and Environmental Movements. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Stephens, S. L., Miller, J. D., Collins, B. M., & North, M. P. (2016). Wildfire impacts on California spotted owl nesting habitat in the Sierra Nevada. Ecosphere. School of Environmental and Forest Science.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service/Endangered Species Program. (n.d.). Endangered Species Act: A History of the Endangered Species Act of 1973. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Welch, C. (2009, January). The Spotted Owl’s New Nemesis. Smithsonian.

White, D. (1994). Defining Old Growth: Implications for Management. USDA Forest Service, 51-62. U.S.D.A.

Wilkinson, Charles. (2000). Messages from Frank’s Landing: A Story of Salmon, Treaties, and the Indian Way. Seattle: University of Washington Press.