Natasha Higbee

I am writing this analysis of U.S. activism during the 1981-90 Contra War in Nicaragua as a queer white student in the United States. Because of my personal perspective, this page focuses on analyzing how activists from the United States and other countries in the so-called “Global North,” or imperialist countries, can forge strong non-exploitative alliances with activists in the “Global South,” or nations facing colonialism.

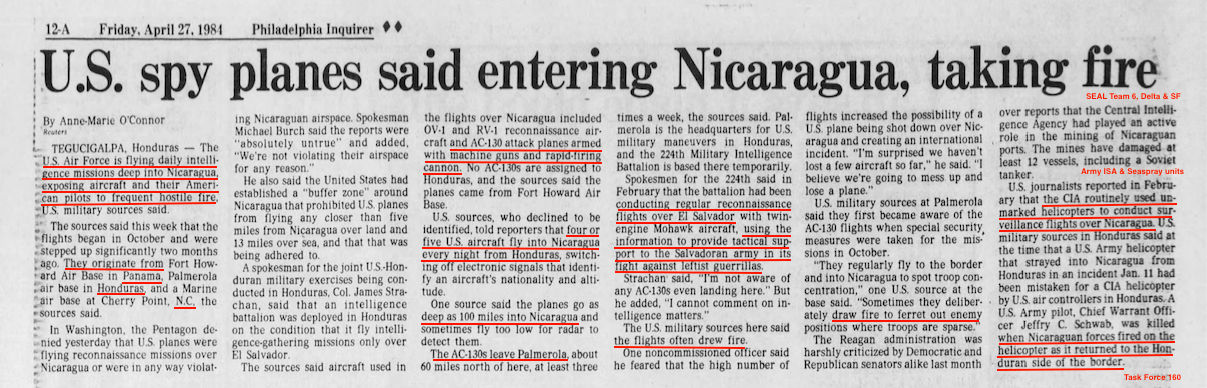

The United States used multiple, inconsistent modes of intervention to dominate Nicaragua. Between 1910 and 1933, for instance, Nicaraguans experienced the following interventions in succession: a U.S.-orchestrated regime change that blocked Nicaragua’s incipient democratic opening; a U.S. invasion and subsequent military occupation; the takeover of Nicaraguan public finances by U.S. dollar diplomats; the spread of U.S. missionary activities and culture industries, especially Hollywood; a second full-scale U.S. invasion; the U.S. military’s campaign to promote democracy; and a six-year guerrilla war (Gobat, 10).

U.S. Imperialism in Nicaragua

U.S. domination and control in Nicaragua did not begin with the Contra war of the 1980s, but rather dates back to the history of colonialism. Just a year after the formation of the United States, Thomas Jefferson declared that the U.S. was invested in creating a canal between the Atlantic and Pacific, and initially sought to make Nicaragua the site of this canal. William Walker later led the ‘Nicaraguan filibusters’, an imperialist private military expedition, that conquered and ruled Nicaragua in 1855-57. In this short time, thousands of people from the U.S. colonized Nicaragua, waging war against the people living there and forcing Nicaraguans off their land. Although these early colonizers were ousted in 1857, a U.S. military occupation of Nicaragua began in 1912 (Gobat).

U.S. Occupation, 1912-33

The military occupation included the U.S. seizing control of Nicaragua’s finances, and quelling the development of agricultural and export-based economic growth in Nicaragua in favor of creating a relationship of economic dependency on the U.S.. United States occupation also contributed to political unrest and the civil war of 1926-27. In the midst of this occupation, Nicaraguan culture and ways of life were also a battleground as U.S Protestant missionaries rushed to ‘Americanize’ the Nicaraguan people (Gobat).

In response to U.S. domination, Augusto César Sandino lead a revolutionary movement of peasants in guerrilla warfare against the occupying U.S. Marines.

In 1927, the U.S. military founded the Guardia Nacional (National Guard), an institution meant to function as both military and police, composed of Nicaraguan citizens led by officers who were largely U.S. Marines. The purpose of this institution was allegedly for stability, but it truly functioned to protect U.S. economic interests and political control in Nicaragua. The United States used a “democratization” campaign in Nicaragua to make the Guardia Nacional the most powerful political force in rural Nicaragua. The campaign created an electoral system where electoral boards (national, departmental, and cantonal, or precinct-level) were headed by U.S. officers or members of the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps who wielded enough control to negate any actions made by Nicaraguan board members (Gobat).

The U.S. military occupation ended in 1933 after Franklin D. Roosevelt became president. Between the Great Depression, the cementing of the National Guard’s power, and the unofficial guerrilla war, the U.S. officially withdrew but Guardia Nacional remained as the base of U.S. power in Nicaragua. With the powerful support of the Guardia Nacional behind him, General Anastasio Somoza Garcia seized control of the country, and soon had the revolutionary Sandino assassinated. Somoza led a harsh dictatorship and was succeeded by his son, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, in 1976 (Hobson).

Sandinistas and the Contra War

In 1961, Nicaraguan revolutionaries founded the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN), or Sandinista Front of National Liberation, to oppose Somoza’s dictatorship. The movement was founded on Marxist principles and the anti-imperialism of its namesake, Sandino. The FSLN waged guerrilla warfare against the Somoza dictatorship, with the support of many Nicaraguan Catholic followers who had been influenced by Liberation Theology, a movement that reexamined Christian scriptures to build a Catholicism that centers the poor and promotes community organizing and activism. Somoza failed to provide relief after a 1972 earthquake devastated the capital city of Managua. The FSLN grew in numbers and began holding territory, all the while fighting a bloody war with the Guardia Nacional. In 1979 Somoza fled the country, and the Sandinistas took power in Managua (Peace).

The Sandinistas quickly created socialist programs that supported workers’ rights, women’s rights, land redistribution, health, and literacy across Nicaragua’s population (Hobson). A backlash against these social reforms added heat to the vitriol the U.S. government held for the Sandinistas under the Carter Administration, and intensified under the Reagan Administration after 1981. Not only was the FSLN government independent from U.S. control, but their programs were successful enough that it looked like they might stay in power. This example was a threat to U.S. imperialist capitalist power in Latin America and the rest of the world. Noam Chomsky describes the success of Sandinista programs and the U.S. government’s reaction:

In 1983, The Inter-American Development Bank concluded that “Nicaragua has made noteworthy progress in the social sector, which is laying the basis for long-term socio-economic development.” The success of the Sandinista reforms terrified U.S. planners. They were aware that – as José Figueres, the father of Costa Rican democracy, put it – “for the first time, Nicaragua has a government that cares for its people.” Back in 1981, a State Department insider boasted that we would “turn Nicaragua into the Albania of Central America” – that is, poor, isolated and politically radical – so that the Sandinista dream of creating a new, more exemplary political model for Latin America would be in ruins. The hatred that was elicited by the Sandinistas for trying to direct resources to the poor (and even succeeding at it) was truly wondrous to behold. Just about all U.S. policymakers shared it, and it reached virtual frenzy (Chomsky).

U.S. Government Response: The Contras

Reagan’s presidency in 1981 initiated an even harsher stance against the new FSLN government. The CIA, allied with the main Nicaraguan base of counter revolutionaries or “contras,” providing funding, leadership, and military training to these contra forces. The School of the Americas trained military from all across Central America, but especially Nicaraguan enlistees, in counterinsurgency tactics and containment of nonviolent radical activists. Some Nicaraguans joined the Contras out of opposition to “godless Communism,” some for money, and some were kidnapped and forced to serve. The Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous Miskito, Sumu, and Rama communities along the Atlantic Coast formed a different section of the rebel movement, based on the long-standing racism and internal colonization they had faced from the mestizo west.

The military strategy used by the main Contra forces consisted of targeting poorly defended rural communities that might be supporting the Sandinistas and slaughtering, torturing, raping, and kidnapping civilians. These Contra forces especially targeted communities that had indicators of social reform such as schools, clinics, schools, and cooperatives (Hobson, Peace).

These gruesome terrorist attacks pressured the Sandinista government to put more and more of its resources towards warfare and defense, pulling money from the social programs that were the foundation of initial Sandinista success (Chomsky).

In 1985, the U.S. government enacted a trade embargo against Nicaragua to weaken the country economically. The Reagan Administration further attacked Nicaragua economically by pressuring the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank to halt all assistance and ongoing projects they had with Nicaragua. The U.S. also mined Nicaraguan harbors so ships could not enter, a move which was condemned by the United Nations and European allies (Chomsky).

The U.S. went on to use false diplomacy to strategically sabotage the February 1990 elections, and dramatically increased the supply of funds to the Contras. The United States made it clear that the only way to end the trade embargo and the Contra campaign of terror was by voting against the FSLN. The Sandinistas lost, but despite the enormous pressures against them, still won 40% of the vote. The U.S. withdrew support for the contras as some of its leaders entered the new conservative government (Chomsky).

The Need for Transnational Solidarity

Transnational solidarity is the practice of creating political unity and bonds of support and connection outside of the confines of a nation-state, sometimes known as “citizen diplomacy” or “globalization from below.” Building movements across these borders is essential, but also full of complications, especially when the bonds are between people in the “Global North,” or imperialist powers, and the “Global South,” the colonized and postcolonial nations of the world. How do solidarity movements build long-lasting, non-hierarchical political community?

Disguised Imperialism?

To uncritically assume that well-intentioned solidarity activism is always a positive force is to allow new forms of exploitation by the Global North, as Jokic observes:

[Activism] is presumably a self-sacrificing, unselfish activity on behalf of another. What is there to morally evaluate if it apparently leaves no room for anything but good? This appearance of being something unquestionably good is, as we shall see, both activism’s advantage and its curse. It is an advantage because it offers a particularly satisfying and comforting aura of moral excellence to those who decide to engage, but it is a curse also because it is a phenomenon that provides wide opportunities for political and other manipulation and abuse.

The guise of ‘assisting’ foreign populations has, both past and present, been used by imperialist powers to justify war, violent coups, colonization, and other atrocities. An early example of this ‘humanitarian’ violence is Rudyard Kipling’s 1899 poem “The White Man’s Burden,” in which he conveys that it is the noble and selfless duty of white men to bring civilization to the inferior beings everywhere else in the world. Imperialism ‘for the good of the people’ today often takes the form of ‘bringing freedom and democracy’ to an area where the U.S. wants control, such as the invasion of Iraq to ‘liberate’ the Iraqi people from Saddam Hussein (Baraka).

Given this historical conflation of humanitarian efforts and imperialism, it is necessary to be wary of international activism that occurs between people living in imperialist nations, the Global North, and people living in colonial or postcolonial countries, the Global South. Well-intentioned activism that does not acknowledge and combat the exploitative power dynamic will often end up perpetuating imperialist, white-supremacist power dynamics. This problematic dynamic can look like a privileged activist going to a community in the Global South to ‘fix’ and ‘save’ the people there, ignoring the competency and agency of the community itself in favor of creating a one-sided ego-boost. Imperialist activism can also look like a group or organization raising funds for an economically disadvantaged community, but stipulating what the money must be used for themselves. Not only is this not helpful, as an outsider will not know the needs of a community, but it is an organization using financial power to enact its will on those with less power.

Nicaragua in 1979-90 faced somewhat less domination or exploitation by well-meaning activists because the Sandinista government, rather than the imperialist U.S., had control and was able to set the terms for solidarity relationships. Transnational solidarity between countries in the Global South generally does not face this danger of reinforcing hierarchical and hegemonic structures of power (Stites Mor).

Will it Last?

How do solidarity movements build long-lasting, non-hierarchical political community? “Project-related solidarity” occurs when political violence, a disaster, or widely recognized human rights abuse inspires support from around the world to influence local politics. When rooted in a specific moment in time or single issue, these ties of solidarity are often short-term rather than long-term (Stites Mor).

Human rights as a framework for political involvement are also less likely to create long-term bonds of solidarity. Activism centering human rights is essentially problematic because it derives from a Western model of political and economic development in which the individual is centered rather than community. It draws from a framework where an individual is given rights based on their ties to a nation-state, and that it is a nation-state’s job (and only their job) to create and enforce the rights of citizens” (Stites Mor).

Discourses of human rights inspire sporadic project-related solidarity, because it often centers on incurred sympathy. Longstanding partnerships require an understanding of and commitment to changing the problems that are often at the core of injustice such as sovereignty, land deprivation, and capitalist socioeconomic injustice. For an organizer from the Global North, this lasting solidarity also requires understandings of how imperialist powers in the Global North have systematically destroyed sovereignty and created systems of dependency in the Global South. In understanding the deep-seated causes of others’ oppression, an organizer from the Global North can also see how their own liberation from patriarchal, imperialist, and white-supremacist forces is inextricably tied to the liberation of residents of the Global South who face these same root problems (Stites Mor).

Transnational solidarity between the Global North and Global South can only be successful and lasting when organizers are self-aware of existing history and power dynamics and seek to follow the leadership of those most impacted.

Activism Within Nicaragua

The Sandinistas were an obvious center of resistance to U.S. imperialism. Within and outside the Sandinista party, women and femmes worked hard in influencing the FSLN to engage with gender equity in a useful way. The activism of women and femme people in Nicaragua combines challenging patriarchal gender relationships with working for the survival of women, femmes, and children. Issues of violence against women and sexual assault are not separate from concerns about medical care, land rights, food access, etc. (Disney).

Miskitu Women and YATAMA

Miskitu women and femmes were central in organizing in the indigenous political movement Yapti Tasba Masraka Nanih Aslatakanka (YATAMA). During the Miskitu-Sandinista conflict of the 1980s, Miskitu peoples were forced en masse into refugee camps as Sandinistas nationalized Miskitu lands that had been used for subsistence and Indigenous sovereignty. Because of the large Miskitu counterrevolutionary presence that this created, Sandinistas occupied Miskitu areas as a continual armed presence and imprisoned Miskitu people. Sandinista Nicaragua and the politics of war masculinized power and reinforced racial hierarchies with mestizo people above Indigenous people, both of which pushed most Miskitu feminine people out of the political arena and toward community-based organizing. Still, feminine people were central peacemakers and negotiators with Sandinistas, while advocating for the lives and self-determination of their communities. One example is the Association of the Atlantic Coast Indigenous Women, which worked against the U.N.’s resettlement proposals (Romero). In 1987, the Miskitu, Rama, and Sumu peoples gained an autonomy from the Sandinista government in northeastern Nicaragua: La Moskitia. The conservative government that followed the Sandinistas in the 1990s was also in conflict with the Miskitu over access to timber and minerals on indigenous land (Grossman).

.jpg?itok=6rwxkUQq)

Nicaraguans Shape U.S. Activism

Nicaraguan activists and Sandinista government officials had a huge role in mobilizing North Americans by strategically sharing information, often heart-rending personal narratives with an emphasis on the U.S. role in their suffering, to most effectively appeal to U.S. residents for aid. This Nicaraguan brilliance and agency in creating communication networks to influence U.S. popular opinion is too often unacknowledged (Perla).

U.S. Solidarity Actions

Sectors of the U.S. public, mobilized by Nicaraguan activists’ testimonios and outreach, formed a broad assortment of grassroots campaigns collectively known as the Central American Peace and Solidarity Movement (CAPSM) worked both to oppose Reagan’s foreign policy, and to build public opposition within the U.S. (Perla).

The Nicaraguan solidarity movement began with Latin@-led organizations such as the Comité Cívico Pro Nicaragua in San Francisco. These early links were largely in Central American immigrant communities in the U.S. who had direct ties and were deeply linked with mobilized organizations and communities in Nicaragua. From there, these North American activists formed grassroots organizations such as the Nicaragua Network in 1979. These organizations focused on mobilizing U.S. residents against U.S. policy in Nicaragua, and worked to create solidarity with Nicaraguan movements. The secular left and liberation theologians in the Catholic Church were main bases for support and activism in CAPSM. This decentralized, grassroots-based movement against the Contra War lasted from 1982 through the 1990 elections when the Sandinistas lost (Perla, Peace).

Types of Solidarity Organizing

Transnational support between U.S. residents and Nicaraguans took an incredible number of forms. Within the country, U.S. activists pressured the government, organized and educated their own communities, raised money for humanitarian aid, and created over eighty sister-city partnerships. A notable program was Oats for Peace, which was created to benefit both U.S. Black farmers and Nicaraguan children. The Nicaraguan Network contacted the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, a network of African American family farm cooperatives, and created a contract with them for over two hundred tons of oats which would be processed into an oatmeal drink for Nicaraguan orphanages and children’s hospitals. Additionally, during the 1980s nearly 100,000 U.S. citizens traveled to Nicaragua as Witnesses for Peace to bear witness to the Contra attacks, to assist in coffee harvests or other work brigades, or to engage in study tours. U.S. residents also staged protests and demonstrations to raise awareness in the United States and pressure the government (Peace).

Problems in the Movement

Despite its beginnings, much of the U.S. organizing was overwhelmingly white. Of 452 Witness for Peace delegates and 129 sanctuary movement activists, 96-98% were white. One can assume that this is not because U.S. residents of color were not interested, but rather because these movements were not an accessible and safe to non-white people, and that non-white needs or perspectives were not prioritized (Peace). Another issue Nicaraguans saw with U.S. solidarity campaigns, especially church-based activist groups, is that they were often depoliticized, not identifying as in solidarity with the Sandinista Revolution but rather as ‘nonpolitical’ or only interested in the human connection aspect. This refusal to politically align with a Marxist anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist agenda, and instead centering a human rights lens, offers less true support to the movement. It reveals a refusal to engage with histories of exploitation and the need for Nicaraguan political and economic self-determination that must be central to any solidarity efforts (Sites Mor).

Furthermore, while the vast number of U.S. visitors to Nicaragua did succeed in raising U.S. consciousness, vast numbers of youth volunteered in fields they had no experience in, such as picking coffee, created large numbers of inefficient workers who needed food and shelter. Despite the good intentions of this activism, it reveals a focus on educating the U.S. activists rather than these activists truly contributing to the struggle in useful ways (Eberhardt).

To build solidarity across these power dynamics, it is necessary to create space for privileged activists the Global North to unlearn their own power and privileged ways of engaging with the world. However, this learning should not be at the expense of the citizens of the Global South.

Gay and Lesbian Solidarity

Networks of explicitly gay and lesbian groups in the U.S. organized in solidarity with Sandinistas, starting in 1978 with the Gay Latino Alliance, the Bay Area Gay Liberation and the mostly white and femme Gay People for the Nicaraguan Revolution (GPNR) in 1979. “By the early 1980s [Nicaraguan Solidarity] became a defining concern of the gay and lesbian left,” (Hobson, 98). The predominantly white Lesbians and Gays against Intervention formed later as an anti-racist, “anti-imperialist, gay liberation, feminist, internationalist, and left” group committed to Latin American struggles with the slogans “Money for AIDS, not war” and “Self-determination/Auto-determinacion,” (Hobson). These communities clearly felt more than just sympathy for Nicaragua. Gay and Lesbian leftist organizers in San Francisco understood that the class, gender, economic, and sexuality-based oppression they faced was inherently linked to the U.S. government’s war against the FSLN.

“Lesbian and gay leftists looked to Nicaragua as the site of a revolution they must defend, as an inspirational model for their own struggles, and as a vehicle for sexual liberation whose meaning could be glimpsed in women seizing arms” (Hobson).

Local History: Olympia and Santo Tomás

There are multiple ties that brought together Olympia, Washington, and Santo Tomás, Nicaragua. One central factor is the Committee for Community Development (CDC) in Santo Tomás, Nicaragua. This group of Santo Tomás residents has been organizing community projects since the mid-’80s, and has created a free lunch program for kids, a community center, a carpenters’ shop, a new school building, a farm, and a water supply, in addition to supporting the clinic and library (Rivas, Know Our People). The CDC also created a women’s sewing cooperative that supplies uniforms for students in the area while teaching local women how to sew, expanding their power and de-commodifying knowledge and skill instruction.

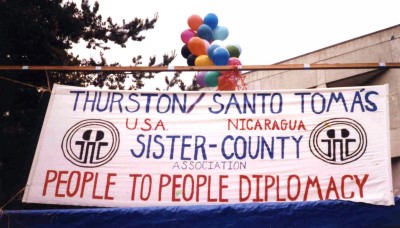

Thurston-Santo Tomás Sister County Association

The Thurston-Santo Tomás Sister County Association (TSTSCA) was formed in 1988 by Olympians who supported Sandinista reforms and opposed their government’s actions to undermine the FSLN. The goals of this organization was to support Santo Tomás community projects, educate U.S. residents of the impacts of U.S. foreign policy, and make meaningful cultural exchanges. This is almost exactly the functions that the Nicaraguan government hoped for sister cities to serve, as Peace describes:

From the Nicaraguan side, sister cities had three principal functions: to establish friendly relations and solidarity with people of different countries; to gain assistance in local development projects; and to resist the Reagan administration’s attempt to isolate Nicaragua internationally and to strangle it economically (Peace).

As referenced before, there are many ways for transnational organizing to be problematic, and there can be a dynamic of imperialism or the “white savior complex” in a U.S. organization raising funds and sending them to a Nicaraguan community to enable the community to improve their quality of life. However, some community members see the support more as paying reparations than just helping out. Edwin Keyt expresses an understanding of history and a sense of obligation rather than charity, saying that he wanted to mitigate “the bad situation that our government had created there…[to help] compensate for what we had done.” As an organization, TSTSCA states that it took leadership from the CDC, supplying funds when asked because of U.S. economic privilege, but following proposals by Nicaraguan organizers. There is much emphasis on the reciprocal and mutually beneficial nature of the relationship (Know Our People).

Julio Rivas, an administrator in the CDC, says that while the funds supporting community projects are incredibly useful to develop community projects, the most important outcomes of the TSTSCA relationship are the ties of friendship, affection, and love (Know Our People).

Olympia Construction Brigade

Another aspect of the relationship is the Olympia Construction Brigade. Jean Eberhardt, whom I spoke to about the history of the Thurston-Santo Tomás connection, first went to Nicaragua in 1985-86 as part of the Seattle Construction Brigade– a group of skilled craftspeople who wanted to counteract the U.S. government’s destruction in Nicaragua by building. They built a rural schoolhouse near Tierra Blanca and worked to bring school desks and supplies to Nicaragua despite the trade embargo. Eberhardt described how there was a need for this kind of construction work in light of the Contras, because “Nicaraguan defense of the country meant that all internal development was halted” (Eberhardt 2017). Jean and her host family on that trip formed the basis for over thirty years of close friendship.

Eberhardt later worked with Olympia community members to form the Olympia Construction Brigade, which Padre Ignacio connected with CDC. They traveled to Santo Tomás, still during the Contra War, to help the CDC build a women’s sewing cooperative.

From her close relationships, Eberhardt discusses how the most impactful aspect of these trips was the human connection in the gesture of solidarity. She describes how important it is to some of her community members in Nicaragua to know that there are people in the United States willing to oppose the government in support of their rights. This is true today as well. Eberhardt said, “I think it means something [for people in Nicaragua] to know that people in the belly of the beast don’t support Trump, don’t support Hillary” (Eberhardt).

Transnational Solidarity Going Forward

Stites Mor asks,“what determines the unity of a political community?” In regards to transnational solidarity, Jean Eberhardt emphasizes longevity and the ability to develop and earn trust when organizing across cultures and privilege. She also emphasizes that in these working relationships, privileged white U.S. citizens absolutely must “take leadership from the people bearing the brunt of the impact” of U.S. foreign policy. Realizing that communities have the solutions to their own problems, and that those experiencing oppression are the best situated to understand the roots and causes as well as the way out of their oppression, is central to overcoming internalized imperialist white-supremacist mindsets. To engage in transnational activism in a non-exploitative and meaningful way, organizers from the Global North must be willing to fully engage with the complex power dynamics at play. This involves examining one’s own power, privilege, and oppression while learning from activists in the Global South about their unique situation in these webs of power, privilege, and oppression.

To bring knowledge, personal awareness, and strength to transnational bonds, organizers creating transnational solidarity must build on a strong foundation of local organizing. Local organizing is a necessary foundation for many reasons. First, organizing within one’s own community is often strongest because it builds on existing social bonds. Organizers in the Global North who start at home can be incredibly effective in raising awareness, educating others, and can work to pressure imperialist governments from within. Furthermore, activist spaces in the Global North are a place where residents of these privileged countries can work together to unpack internalized imperialist or white-supremacist mentalities without burdening activists in the Global South.

The most essential, core aspect of transnational solidarity, is human connection. In an individualist, capitalist society, bonds of love and caring are an act of rebellion. This is even more true when these connections cross divides of language, place, power, and state borders. Humans who unite and stand together with love and understanding are unstoppable.

Sources

Baraka, A. (2013, June 4). Syria and the Sham of “Humanitarian Intervention.” Common Dreams.

Becker, A. (2012, August 2). Bonds beyond borders. Real Change.

Chomsky, N. (2006, September 8). The contra war in Nicaragua. Libcom.org.

Disney, J. L. (2008). Women’s Activism and Feminist Agency in Mozambique and Nicaragua. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Dixon, Chris. (2014). Another politics: talking across today’s transformative movements. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Eberhardt, Jean. (Personal Communication, February 21, 2017).

Eberhardt, J., & Cox, G. (2013, December 10). Memories of the Olympia to Nicaragua Construction Brigade, 25 years later. Works in Progress.

Gobat, M. (2005). Confronting the American Dream Nicaragua Under U.S. Imperial Rule. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Grossman, Zoltán. (2007). Marxism & Indigenism: Relations Between Left and Indigenous Movements [Powerpoint Slides].

Hale, C. R. (1994). Resistance and contradiction: Miskitu Indians and the Nicaraguan State, 1894-1987. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

Hobson,, Emily K. (2016). Lavender and red: liberation and solidarity in the gay and lesbian left. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Jokic, A. (2013). Go local: morality and international activism. Ethics & Global Politics, 6(1), 39–62.

Mejia, C. (2012, October 8). U.S. Imperialism in Nicaragua. One Struggle.

Merrill, R. (2005, May 11). Sandino and Nicaraguan Resistance Against American Imperialism. 4StruggleMag.

Meyer, D. (n.d). Letter from Nicaragua…The Artesano Project. Traditions Cafe.

Olympia/Santo Tomas Quarterly. (2006) Thurston-San Tomas Sister County Association, 6(1).

Olympia/Santo Tomas Quarterly. (2008) Thurston-San Tomas Sister County Association, 8(1).

Olympia Fellowship of Reconciliation. (2013). Decades Of Solidarity With Santo Tomas Nicaragua. Youtube.

Peace, Roger C. (2012). A call to conscience: the anti/Contra War campaign. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Perla, H. (2013). Central American counterpublic mobilization: Transnational social movement opposition to Reagan’s foreign policy toward Central America. Latino Studies; Basingstoke, 11(2), 167–189.

Romero, D. F. (2012). Miskitu Women and Their Social Contribution to the Regional Politics of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 8(4), 447–465.

Stites Mor, J. (2013). Critical Human Rights : Human Rights and Transnational Solidarity in Cold War Latin America. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Thurston-Santo Tomás Sister County Association. Know Our People/Conocer a Nuestro Pueblo [DVD Documentary].

Works In Progress. (2008, May). The Thurston-Santo Tomás Sister County Association welcomes its 9th Community Delegation from Santo Tomás, Nicaragua.