Protoperidinium

Common Name: Whirl Round

By: Mishauna Watkinson

General Information

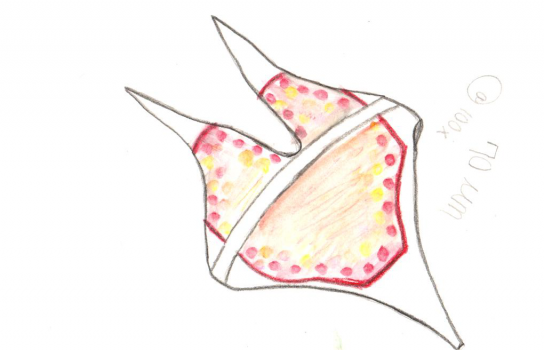

Protoperidinium comes from protos, meaning first, while peridineo means to whirl around, both stemming from Greek origin. Protoperidinium are part of the dinoflagellate phylum and belong to the order Peridiniales( Hayashi et al, 2007). Gómez (2005) described 264 species of Protoperidinium which can be found globally. Protoperidinium range between 50µm -100µm and can be red, brown, or yellow in the inner parts of the organism depending on their diet (Hayashi et.al, 2007). Protoperidinium have armored cellulose thecal plates on the outside with apical or antapical horns or spines. The organism is divided by its plates into an upper and lower part of the organism. The Protoperidinium genus is divided into two subgenera Protoperidinium and Archaeperidinium on the basis of numbers of thecal plates (2-6) (Gul et al.,2014). A flagella (tail) is located between the horns that allows the Protoperidinium to maneuver around.

Ecology

These organisms can be found in both coastal and oceanic waters, preferring warmer to tropical climates  (Johannesson et al, 2000). They capture individual phytoplankton cells, sometimes nearly as large as themselves and either engulfs the entire cell or transfer body fluids of the captured call into themselves by way of a pallium or a peduncle. This pallium is made from cytoplasm within the Protoperidinium; some of their main prey consists of Ditylum brightwellii, Thalassiosira sp., and Gonyaulax polyedra (Buskey, 1997). Protoperidinium are known to be “picky eaters” Some species of Protoperidinium, have been shown to survive for extended periods of time, up to 71 days in the case of P. depressum, in conditions of starvation or extremely low food availability (Gibble et al. 2007).

(Johannesson et al, 2000). They capture individual phytoplankton cells, sometimes nearly as large as themselves and either engulfs the entire cell or transfer body fluids of the captured call into themselves by way of a pallium or a peduncle. This pallium is made from cytoplasm within the Protoperidinium; some of their main prey consists of Ditylum brightwellii, Thalassiosira sp., and Gonyaulax polyedra (Buskey, 1997). Protoperidinium are known to be “picky eaters” Some species of Protoperidinium, have been shown to survive for extended periods of time, up to 71 days in the case of P. depressum, in conditions of starvation or extremely low food availability (Gibble et al. 2007).

Gaining more knowledge on these organisms within the 21st century is a must! Protoperidinium feed primarily on diatoms and other dinoflagellates which have been known to cause red tide. Some species such as Protoperidinium crassipes are the putative source of azaspiracid (AZA) a shellfish toxin (Gibble et al. 2007) It is important to study their feeding habits and general characteristics to gain more knowledge on how it is these organisms can help us naturally deplete red tides by grazing. Algae blooms affect our local shellfish production as well as other organisms and with the help of species Protoperidinium we could lessen their effects. Gibble et al. (2007) found various species of Protoperidinium off the coast of Ireland and found that depending on their abundance a change from the composition of the marine environment; phototrophic dinoflagellates dominated the plankton community nearshore, whereas diatoms dominated offshore. Furthering this study in other parts of the world could help us understand how microbial organisms affect our plants and play a natural role in the cleaning up of our plant.

Protoperidinium while small work in numbers to deplete red tides. These organisms can symbolize that working together can help solve bigger problems. For example in Gibble et al. (2007) “Protoperidinium and other microzooplankton may play an important role in control of phytoplankton populations. In the waters off the southwestern coast of Ireland at the time of this study, Protoperidinium spp. were likely competing with other consumers of large phytoplankton, including copepods and other heterotrophic dinoflagellates, particularly Noctiluca scintillans, which was abundant… Growing evidence indicates that the impact of microzooplankton like Protoperidinium on phytoplankton populations, bloom structure and cycling of organic matter can be important—even more significant than that of mesozooplankton.” Like the various species of Protoperidinium our various cultures need to work together in solving our current global crisis.

Protoperidinium while small work in numbers to deplete red tides. These organisms can symbolize that working together can help solve bigger problems. For example in Gibble et al. (2007) “Protoperidinium and other microzooplankton may play an important role in control of phytoplankton populations. In the waters off the southwestern coast of Ireland at the time of this study, Protoperidinium spp. were likely competing with other consumers of large phytoplankton, including copepods and other heterotrophic dinoflagellates, particularly Noctiluca scintillans, which was abundant… Growing evidence indicates that the impact of microzooplankton like Protoperidinium on phytoplankton populations, bloom structure and cycling of organic matter can be important—even more significant than that of mesozooplankton.” Like the various species of Protoperidinium our various cultures need to work together in solving our current global crisis.

Literature Cited

Buskey, E. J. 1997. “Behavioral Components of Feeding Selectivity of the Heterotrophic Dinoflagellate Protoperidinium Pellucidum.” Marine Ecology Progress Series 153: 77-89. http://www.int-res.com/articles/meps/153/m153p077.pdf

Encyclopedia of Life (EOL). 2012. Protoperidinium oceanicum (Vanhoffen) Balech 1974. https://www.eoas.ubc.ca/research/phytoplankton/dinoflagellates/protoperidinium/p_oceanicum.html

Gómez, F. 2005. A list of free–living dinoflagellate species in the world’s oceans. Acta Botanica Croatica, 64: 129-212.

Gribble KE, Nolan G, Anderson DM. 2007. Biodiversity, biogeography and potential trophic impact of protoperidinium spp. (dinophyceae) off the southwestern coast of ireland. J Plankton Res. 29(11):931-47. http://www.whoi.edu/fileserver.do?id=45411&pt=2&p=28251

Gul, Sadaf ; Farrakh Nawaz, Muhammad. 2014. The Dinoflagellate Genera Protoperidinium and Podolampas from Pakistan’s Shelf and Deep Sea Vicinity (North Arabian Sea). Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. Faisalabad, Pakistan. http://www.trjfas.org/uploads/pdf_110.pdf

Hayashi, Kendra; Q. Jacox,Jenny; Glanz, Jessica; Alvarado, Nilo; Kudela, Raphael; Rosen, Barry H. ; and Coale, Susann ,2007. “Phytoplankton Identification: Protoperidinium.” Kudela Lab, Santa Cruz, CA. http://oceandatacenter.ucsc.edu/PhytoGallery/Dinoflagellates/protoperidinium.html

Johannesson, Bo, Larsvik, Martin, Loo, Lars-Ove, Samuelsson, Helena, 2000. “Protoperidinium-dinoflagellates.” Aquascope. Tjärnö Marine Biological Laboratory, Strömstad, Sweden. http://www.vattenkikaren.gu.se/fakta/arter/algae/mikroalg/protspp/protspe.html