Have you ever come across a tree that captivates your attention? A tree that is both mystical and glorious? Ever visited the Redwood Forest that borders northern coastal California? Did you happen to drive through the giant sequoia trees? (If not then you can plan your trip by visiting Visit California‘s website or Redwoods Info website.) If you answered yes to any of these questions then you may be familiar with the cedar family. You may also be acquainted with our own Pacific Northwest native western red cedar.

Morphology

| Plant Classification | |

| Common Name: | Western Red Cedar |

| Family: | Cupressaceae |

| Genus: | Thuja |

| Species: | T. plicata |

Thuja plicata is a large evergreen tree that can reach up to 60m in height with a droopy leader (the top of the tree). Its branches swoop down and then back up to form a ‘J’ shape with horizontally flattened branchlets. It has fibrous reddish brown to gray bark and very aromatic wood. The leaves are glossy green and they turn brownish with age.

Photo by: Chantay Anderson

Cedar Cones

They are scale-like and closely appressed in an overlapping shingled arrangement. It also has numerous small egg-shaped cones that are about 1cm in length (Pojar et al. 1994).

Cultural Uses

Photo by: Monica Teeais

A basket, hat and cape all made from cedar!

To many of our Pacific Northwest Native American tribes, western red cedar was and still is considered to be a tree of life. But why is it called a tree of life? Well this particular tree provided many every day materialistic essentials. Planks for their winter houses, fishing traps, baskets and buckets, canoes, clothing, baby boards were all made from this magnificent tree. However, T. plicata was used for more than just materialistic essentials; it was used in rituals of all kinds including for burial and mourning rituals (Haeberlin and Gunther 1930). It has a multitude of purposes, being used for pretty much everything you can think of. You can see some cedar made artifacts by visiting the Squaxin Island Tribe Museum.

Dugout Canoes

Dugout canoes are iconic structures made by Pacific Northwest Indigenous people. They were essential for transportation via waterways. This transportation was extremely

Photo by: Monica Teeais

Canoe Journey Canoes

important for going to war or for hunting, fishing and collecting as well as being able to attend pot latch in other tribal communities. Today our Northwest tribal nations from Canada and the United States participate in what is known as the Canoe Journey to celebrate their culture, much like a traditional pot latch. The canoes that are built for this adventure are still made from cedar wood; however, a large enough western red cedar tree that is of high quality is becoming scarce and costs a fortune to obtain (Deline 2013). The only place a tree this large exists is in a old-growth forest. In this region old-growth forests are almost non existent due to logging in these ecosystems. The canoe journey is open to the public and is a lot of fun! To learn more about last year’s canoe journey click here and to learn more about this year’s upcoming journey click here. Want to learn more about the making of a traditional canoe? Click here (watch all 11 videos).

Photo by: Monica Teeais

Medicinal Uses

Photo by: Chantay Anderson

This tree wasn’t only used for everyday items, but also has numerous medicinal properties. T. plicata possesses effective antifungal and antibacterial properties. Indigenous people used parts of the tree for treatment of stomach aches, colds, toothaches, arthritis and other illnesses or pains (Plants…c1996-2012). The leaves are used to make tinctures that help with a variety of fungal infections like ringworm and athletes foot. Tinctures or teas can help with bronchial conditions, soothe sore muscles and help with reproductive problems. Western red cedar is also an immunostimulant and small daily doses can help to prevent respiratory and intestinal infections (Moore Michael 1993). The Colville tribe used an infusion of the branches as dandruff or other scalp infections shampoo (Moerman 1998).

Chemical Compounds

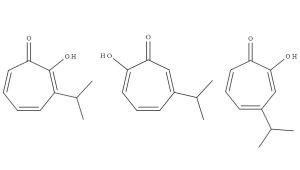

So why did Native American people use this tree for practically everything? Why did

Alpha-, Beta-, and Gamma- thujaplicin isomers

they choose T. plicata for the making of their canoes? The answer is found in one of the compounds located in the heartwood of T. plicata, a monoterpene called thujaplicin. This particular compound has antifungal and antibacterial properties. Thujaplicin has three isomers: α-, β-, and γ-thujaplicin (Rennerfelt Erik 1948). Studies have shown that β-thujaplicin provide antifungal and antibacterial properties, which explains why it was used for the treatment of many illnesses. Additionally, it was used for treatment of an ear infection caused by Malassezia pachydermatis (Nakano Y et al. 2005) and it helped with the treatment of dermatitis (Arima Y 2003).

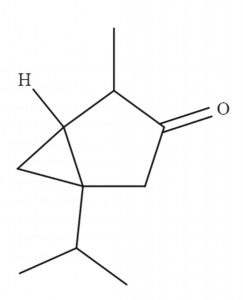

Structural Formula of Thujone

Although the Native Americans used the leaves in many of their remedies, it contains a neurotoxin called thujone, so I do not recommend treating yourself of any ailments without seeking medical advice first. Thujone is a monoterpene and a ketone that is used as an active ingredient in some cold medicines like nasal decongestants and cough suppressants; it is also used in a few other everyday items (Tsiri et al. 2009). Over consumption of thujone can lead to side effects consisting of nervous agitation, chronic convulsions, renal and liver toxicity, brain toxicity, epileptic seizures, vertigo, anxiety and so much more (Naser et al. 2005; HealWithFood…c2010-2017).

Defenses

These compounds provide important ecological functions for the tree itself. Thujaplicin have resilient antifungal properties that fight off harmful decay causing fungi, making the wood extremely durable. In fact, it is believed that the γ-thujaplicin isomer prevents fungal decay (Rennerfelt Erik 1948). Also, the toxicity of the leaves provide defense against herbivores. Many monoterpenes are toxic to mammals because it impedes rumen microbial activity (Vourc’h et al. 2001). Rumen microbes located in the stomach of herbivores help to digest cellulose.

Photo by Chantay Anderson

It is no wonder why cedar wood is so desirable for the construction of houses, decks, fences, canoes/boats, furniture and so much more! If you are interested in learning more about this tree click here.

References

Arima Y. Antibacterial effect of beta-thujaplicin on staphylococci isolated from atopic

dermatitis: relationship between changes in the number of viable bacterial cells and

clinical improvement in an eczematous lesion of atopic dermatitis. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2003;51(1):113–122.

Deline Rich. c2013. Introduction- NW Coast Indian Canoe Project. [Internet]. [cited 2017

Feb 13].

Available from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_HOla2FjFE

Deline Rich. c2013. Selecting a Tree- NW Coast Indian Canoe Project. [Internet]. [cited

2017 Feb 13].

Available from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YBcB5U_7uNE&t=2s

Haeberlin Hermann, Gunter Erna. 1930. The Indians of Puget Sound. Anthroplogy.

4(1):1-84.

HealWithFood. Thujone in Sage Tea – Should You Be Worried About Side Effects?.

c2010-2017 [Internet]. [cited 2017 Feb 9].

Available from

http://www.healwithfood.org/side-effects/sage-tea-thujone-toxic-dose.php

Moerman, Daniel E. 1998. Thuja plicata. In: Native American ethnobotany. Portland,

Oregon: Timber Press. p. 558-561.

Moore Michael. 1993. Red Cedar. In: Medicinal Plants Of The Pacific West. Santa Fe,

New Mexico: Museum of New Mexico Press. 209-212.

Nakano Y, Wada M, Tani H, Sasai K, Baba E. Effects of β-Thujaplicin on Anti-Malassezia

pachydermatis Remedy for Canine Otitis Externa. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 2005;67(12):1243–1247.

Naser B, Bodinet C, Tegtmeier M, Lindequist U. Thuja occidentalis(Arbor vitae): A Review

of its Pharmaceutical, Pharmacological and Clinical Properties. Evidence-Based

Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2005; 2(1):69–78.

Plants For A Future. Thuja plicata – Donn. ex D.Don. c1996-2012 [Internet]. [cited 2017

Jan 17].

Available from

http://www.pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Thuja+plicata

Pojar J, MacKinnon A, Alaback PB. 1994. Plants of the Pacific Northwest coast:

Washington, Oregon, British Columbia & Alaska. Redmond, WA: Lone Pine Pub.

41-42.

Rennerfelt Erik. 1948. Investigations of Thujaplicin, a Fungicidal Substance in the

Heartwood of Thuja plicata D.Don. Physiologia Plantarum. 1(3):245-254

Tsiri D, Graikou K, Pobłocka-Olech L, Krauze-Baranowska M, Spyropoulos C, Chinou I.

Chemosystematic Value of the Essential Oil Composition of Thuja species

Cultivated in Poland—Antimicrobial Activity. Molecules. 2009; 14(11):4707–4715.

Vourc’h Gwenaël, Martin Jean-Louis, Duncan Patrick, Escarré José and Clausen Thomas

P. 2001. Defensive Adaptations of Thuja plicata to Ungulate Browsing: A

Comparative Study between Mainland and Island Populations. Oecologia.

126(1):84-93