Because of the rich soils brought down by rivers, people all over the world have farmed and lived near river deltas. The Nisqually watershed is the ancestral home of the Nisqually Indians who have lived here for thousands of years. They have fished in the Nisqually River, built seasonal villages along the banks, and used the estuary and mudflats to harvest shellfish. They have managed the land along the river and its tributaries to provide for their needs. In 1830, the Hudson Bay Company established Fort Nisqually up on the bluff where the city of DuPont is now and they began European-style farming in the area. In 1854, The Medicine Creek treaty was signed here by representatives of the US government and the tribes of South Puget Sound. The treaty ceded Nisqually Tribal lands along the 78-mile river and its tributaries to the U.S. Government. It moved the Nisqually people to a tiny reservation (on a rocky bluff with no access to the river) and guaranteed them rights to hunt and fish in their usual and accustomed places. So small was the allocated reservation that tribal members, led by Chief Leschi, fought back. Eventually, Leschi was falsely accused of murder and hung. But the Nisqually Reservation was moved and expanded. In 2004, Leschi was exonerated.

Because of the rich soils brought down by rivers, people all over the world have farmed and lived near river deltas. The Nisqually watershed is the ancestral home of the Nisqually Indians who have lived here for thousands of years. They have fished in the Nisqually River, built seasonal villages along the banks, and used the estuary and mudflats to harvest shellfish. They have managed the land along the river and its tributaries to provide for their needs. In 1830, the Hudson Bay Company established Fort Nisqually up on the bluff where the city of DuPont is now and they began European-style farming in the area. In 1854, The Medicine Creek treaty was signed here by representatives of the US government and the tribes of South Puget Sound. The treaty ceded Nisqually Tribal lands along the 78-mile river and its tributaries to the U.S. Government. It moved the Nisqually people to a tiny reservation (on a rocky bluff with no access to the river) and guaranteed them rights to hunt and fish in their usual and accustomed places. So small was the allocated reservation that tribal members, led by Chief Leschi, fought back. Eventually, Leschi was falsely accused of murder and hung. But the Nisqually Reservation was moved and expanded. In 2004, Leschi was exonerated.

The Treaty opened the land to more settlement. The first were the McAllister and Shazer families. In 1904 the Brown family purchased the west side of the delta and built dikes to separate the rich farmland from the salty waters. The Braget family built dikes on the east side. At the time, salmon were plentiful so they did not care that they were closing off a productive saltwater nursery for salmon. They also imported their favorite pasture grasses, such as Reed Canary Grass, not realizing that these grasses would eventually spread along fresh waterways throughout the watershed choking stream flow and out-competing the native plants.

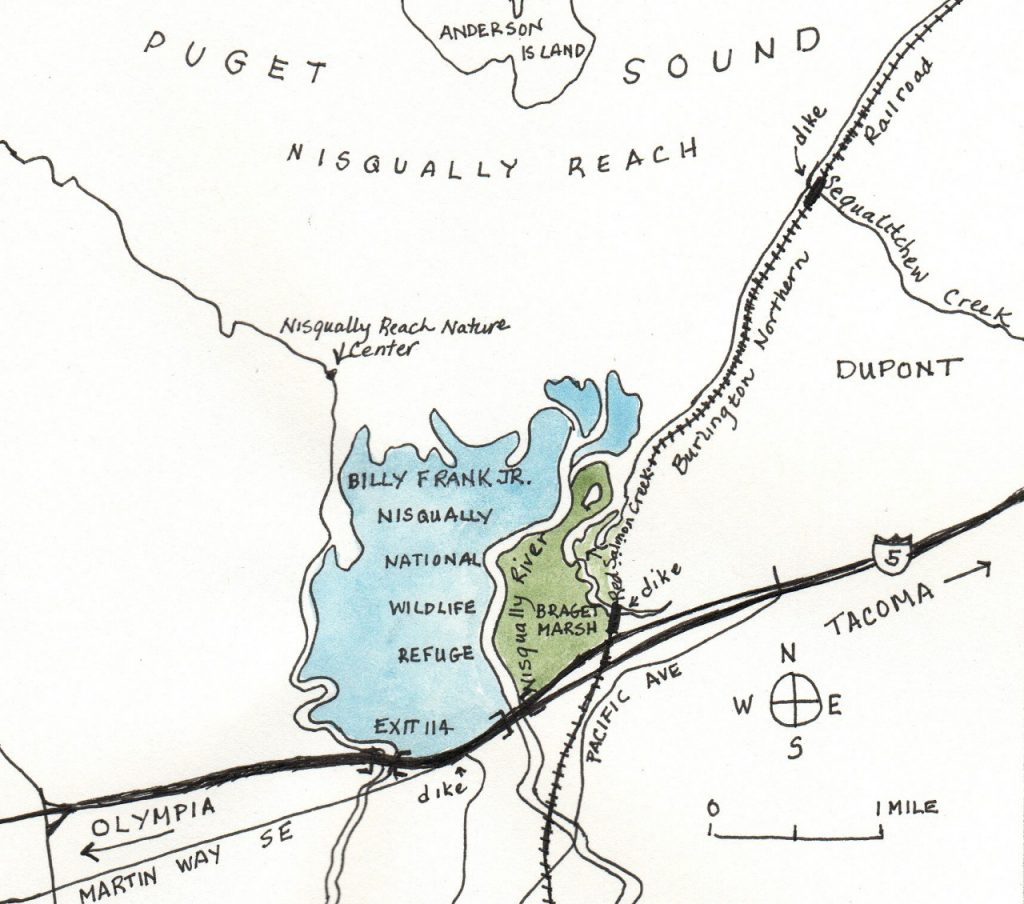

The Puget Sound waterways have always been used for transportation, so when the railroads came, it made sense to build them along the Sound. Dikes rather than bridges were built across estuary entrances (all along Puget Sound). These dikes further constricted the flow of salt water through cement pipes in the dikes. State and Interstate Highway engineers created new dikes, such as those carrying Interstate 5. See the map below. The red lines indicate where dikes existed prior to removal.

Before the Restoration

While many people benefitted from the agricultural products and easy transportation, the habitat for wild species of plants and animals was severely restricted. Major species affected included the wild salmon that rely on the protection and food of the estuary before beginning their long sea journey. Due to overfishing, dams, agricultural run-off, pesticides, heavy logging near streams, and dikes, many species of salmon suffered. The local way of life for tribes and non-native fishing families became more difficult. The invasive Reed Canary Grass spread, restricting access to fresh waterways for diverse species of wildlife.

In 1974, with the concerted efforts of local citizen groups, the United States Government purchased the west side of the delta to create the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge. In 2000, the Nisqually Tribe purchased the east side of the delta from farmer Kenny Braget. After a pilot project in 1996, the Nisqually Tribe led the effort to remove agricultural dikes to flood the delta along the east side of the river, 31 acres in 2002 and 100 acres in 2006. The salt water flowed in to help restore the estuary. In 2009, the U.S. Government followed this lead by removing dikes at the refuge. A new boardwalk gives visitors access to the estuary’s salt marsh. Future plans call for the elevation of Interstate 5 and restoring openings in the railroad dikes across stream entrances between Nisqually and Tacoma.

In December 2015, the Billy Frank Jr. Tell Your Story Act, changed the refuge name to Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge to honor Billy Frank Jr., a Nisqually tribal leader who challenged Washington State and the United States Government to honor the Medicine Creek Treaty. The act also established the Medicine Creek Treaty National Memorial within the boundaries of the refuge. Billy Frank Jr. was the architect of a cooperative system for fisheries management.

To learn more visit the resources page.