|

Plant Classification |

|

|

Family |

Ericaceae |

|

Genus |

Gaultheria |

|

Species |

Gaultheria shallon |

|

Common Name |

salal |

Salal (Gaultheria shallon) is a dominant understory shrub native to coastal regions of California, Alaska, and the Pacific Northwest. It’s easy to recognize because of its shiny, sturdy, evergreen leaves that feel thick and leathery. Mature plants have reddish brown stems that contrast beautifully with the brightness of the leaves, while younger stems are green. When ripe, the fragrant berries taste sweet, slightly tart, and robust with a mealy texture and make delicious jams and wines. Their deep blueish purple color will stain fingertips and nearby sidewalks alike. Additionally, salal berries preserve well when dehydrated; coastal indigenous groups have prepared “cakes” out of the berries that lasted well into the winter. The leaves have potent anti-inflammatory properties and can be used safely in many ways. Prepared as tea or tincture they help with bladder inflammation, ulcers, stomach cramps, diarrhea, menstrual cramps, can reduce fevers, and soothe sore throats. You can chew the leaves, spit out the mush, and apply it onto wounds and sores to help heal.

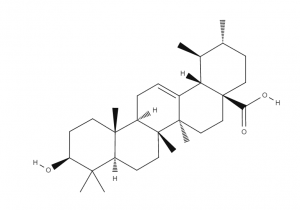

Salal leaves are rigid and long lasting because they have an outer waxy coating called epicuticle. One of the main chemical compounds of the epicuticle is ursolic acid, which is a water insoluble triterpene that forms a protective barrier and helps the plant protect itself against overexposure to light, desiccation, and radiation. Ursolic acid makes the leaves rough and contributes to their somewhat bitter taste, which also discourage herbivory. Another important chemical compound is galangin, which is a flavonoid and more specifically an anthocyanin that adds color and antioxidant properties to the berries. Galangin plays a role in the preservative properties of the berries mentioned earlier.

Galangin

Salal’s waxy leaves and rigid stems bring structure and durability to bouquets, wreaths, and other popularly used floral arrangements. Over recent years, international demand from the floral industry has soared for salal, with its highest demand coming from Europe. Salal and other forest products such as moss and ferns now make up a huge global industry that in 2006 was generating at least $250,000,000 per year, which at the time equaled nearly one fourth of the state’s apple industry as reported by The Seattle Times. Most of the profits go to wholesalers and companies involved in commercial exportation. As a native floral green, salal grows abundantly and under different levels of supervision and land ownership: national and state forests and parks, city lands, and privately-owned lands including large industrial companies. This translates into an industry that greatly depends on landless harvesters who access their product by means of permits and leases. Having varying levels of requirements for identification, licenses, and insurance attracts undocumented workers while also significantly loosening accountability around labor conditions, working wages, and competitive dynamics with other harvesting groups or corporations. This complex set of systems highlights the impact of globalization where labor increasingly flows into the US from under resourced countries while the product itself grows in value through its distribution to increasingly broader and distant markets. Free trade agreements are similarly tied to both the movement of salal and humans across international borders.

Ursolic Acid

Harvesting forest products like salal is nothing new. The industry first developed at the beginning of the 20th century by European-American groups seeking extra income, and it wasn’t until closer to 1970 that political refugees and other displaced groups mostly from Southeast Asia, Cambodia, and Laos took up this work. By 1990, more immigrant workers from Central and South America made up the workforce because harvesting floral greens presented a viable alternative or complement to agricultural work in California, Oregon, and eastern Washington. Today, Latin@ individuals and families represent the majority along with a smaller proportion of Southeast Asian immigrants and even fewer European-Americans. The majority of those who “pick brush” as a main source of income tend to be undocumented, with little to no formal educational backgrounds, and generally lacking the English s

kills to be self-sufficient. Safety in the woods for a community of workers trying to keep a low profile is a serious issue, from a young man shot by hunters in 2010 to several reported instances of stolen products and van crashes. This connects salal to a complex set of issues surrounding labor conditions, liveable wages, exploitation of immigrants, and resource sustainability within a multi-million global flower industry. All in our PNW backyard, leading us back to this seemingly unassuming shrub.

Taken by Stefanie Gottschalk Huerta

REFERENCES

Featured image under headline from Wedding Flowers and Reception Ideas, [internet] [accessed 3/18/17]. Available from http://www.wedding-flowers-and-reception-ideas.com/white-daisy-wedding-bouquet-salal-leaves.html

Fraser, Lauchlan et al. The biology of Canadian weeds 102. Gaultheria shallon.

Vancouver, Canada: Canadian Journal of Plant Sciences, 1993.

Sierra Club British Columbia Organization Site. 2009, [internet] [accessed 3/11/17]. Available from http://sierraclubbc.scbc.webfactional.com/education/ecomap/coasts-mountains/2salal

Erica Schultz. Salal Harvest: Pick of the Floral Season. 2010, [internet] [accessed 3/11/17].

Available from http://www.erikajschultz.com/salal-harvest-pick-of-the-floral-season

Blog post by Grow Forage Cook Ferment, Foraging for Salal Berries, [internet] [accessed 3/11/17].

Available from http://www.growforagecookferment.com/foraging-for-salal-berries/

Devon Peña. Salal: Food, Medicine, and Culture of the Coast Salish Peoples, [internet] [accessed 3/11/17].

Available from http://www.goodfoodworld.com/2013/01/salal-food-medicine-and-culture-of-the-coast-salish-peoples/