By Sarah Dyer

INTRODUCTION

Solanum aethiopicum ‘Gilo’, commonly known as Ethiopian eggplant, scarlet eggplant, garden egg, garden huckleberry, or bitter tomato, is a member of the Solanum genus, which includes crops like tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, and tobacco, as well as Solanum melongena, the common Asian eggplant (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Gilo has long been a beloved vegetable in African, Asian, Caribbean, and Brazilian cuisine, and is prized for its essential nutrients such as vitamins A and C, calcium, and iron, and its unique, slightly bitter flavor profile that deepens as the fruit ripens. In addition to its culinary appeal and nutritional benefits, S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ presents a compelling case for the exploration of novel crops in regions like the Pacific Northwest (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153).

The increasing global interest in diverse and nutrient-rich crops has elevated the significance of exploring African eggplant’s potential beyond its native regions, and the inquiry into the feasibility of cultivating Gilo in a non-traditional environment raises pertinent questions regarding its resilience to local climate conditions, its impact on environmental sustainability, its contribution to scientific research, and its potential economic viability as a cash crop (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Beyond these practical considerations, the cultural and social implications of introducing S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ to both a familiar and a new audience also invite examination, offering insights into intercultural exchanges and potential shifts in dietary practices (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). By delving into the complexities of incorporating ‘Gilo’ into a different agricultural landscape, researchers and stakeholders stand to gain valuable insights into the broader implications of diversifying food production and enhancing culinary diversity in emerging markets.

1. BACKGROUND: ORIGIN AND HISTORY

1.1 African Origins

The journey of Gilo’s cultivation and propagation has been shaped by the diverse landscapes and climates in which it thrives. S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ is considered an old-world vegetable, meaning it has origins in Africa, Asia, or Europe; its center of origin is West Central Africa, where it descended from its wild ancestor Solanum anguivi, and has been cultivated and consumed for centuries by various cultures, adapting to diverse climates and landscapes across the continent, spanning from southern Senegal to Nigeria, across Central Africa to eastern Africa, and from Central Africa to Morocco, Angola, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique (Daunay et al., 2000; Han et al., 2021; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Morphologically, Gilo stands as a subspecies of the broader S. aethiopicum genus, highlighting the genetic diversity within the Solanaceae family and its resilience and versatility as a crop (Daunay et al., 2000). Its adaptive qualities enabled its spread beyond Africa into regions like Asia, underlining its ability to thrive in varied environments and climates, and transcend geographical boundaries (Lalhmingsanga et al, 2018).

1.2 Global Spread and Transcontinental Movement

The movement of Gilo to other continents was further facilitated by European colonialism and the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which saw the vegetable being introduced to the Americas, specifically Brazil and the Carribean, as well as Europe (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2024; Han et al., 2021; Mangan et al., 2024). In fact, the name ‘eggplant’ comes from S. aethiopicum’s introduction to London by British traders in the 1500s; originally called the “Guinea squash”, the fruit’s white color and ellipsoid shape led to the name “eggplant” (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Around the same time, another vegetable arrived from Asia with similar culinary characteristics, but larger, purple, and irregularly shaped fruits; for a while, both plants were used, but eventually, the “Guinea squash” was forgotten and fell out of Western cuisine, leaving behind its name as its early presence in Europe (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). The historical trajectory of S. aethiopicum from its African roots to its integration into diverse culinary traditions illuminates the interconnectedness of food cultures and agricultural practices, highlighting its enduring legacy in shaping diets and livelihoods around the world, as well as serving as a symbol of sustainability and resilience in agricultural practices across different regions (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153).

2. OVERVIEW OF CULTIVATION

2.1 Cultivation Practices for S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’

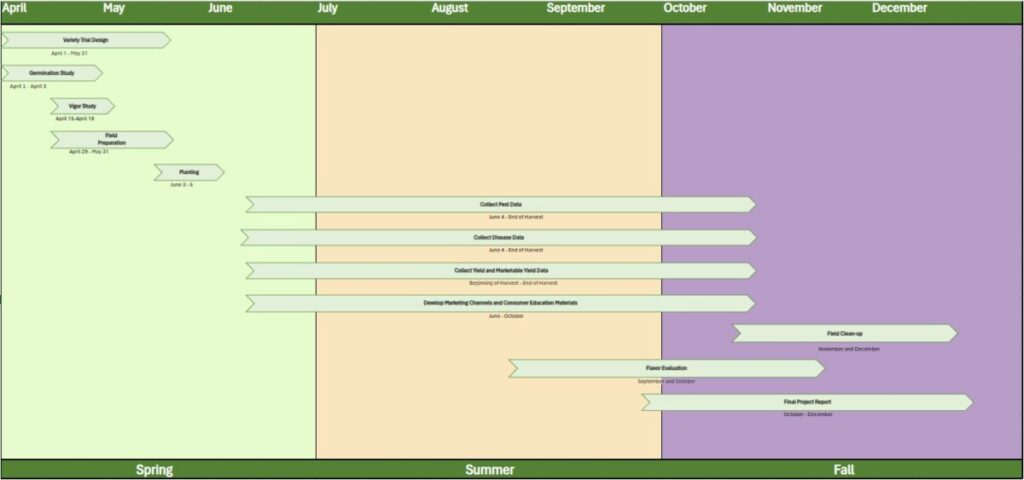

While traditionally grown in tropical and subtropical climates, S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ may be adapted to the Pacific Northwest climate with careful attention and management. The region’s mild climate, coupled with greenhouse germination to provide the necessary warm and humid conditions, could potentially support the cultivation of this unique crop (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Gilo should be planted in the spring and typically takes between 65-120 days to mature, depending on the variety and growing conditions; growing to a height of 2-3 feet, it produces small white flowers that eventually develop into small, oblong fruits that are a hallmark of the ‘Gilo’ variety (Han et al., 2021; Hill, 2001; Mangan et al., 2024; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Fruits can be white, yellow, green, purple, black, orange, and red, and are eaten at all stages of ripeness, though they are often preferred when they are white, yellow, or green and immature (Han et al., 2021; Mangan et al., 2024).

2.2 Adaptation to Pacific Northwest Climate

Starting S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ in a non-tropical climate requires a different approach compared to traditional European eggplant varieties (Mangan et al., 2024). Gilo is commonly found in humid areas all over tropical Africa where its members grow best with temperatures of 77–95 °F and 68–80.5 °F, day and night temperatures, respectively (Han et al., 2021; Hill, 2001; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). To maximize growth in the field, it is recommended to start African eggplant transplants earlier than the European eggplant varieties; European eggplant varieties are typically started 6-8 weeks before transplanting, and it is suggested to start seeds of African eggplants 9-10 weeks before transplanting in regions like the Pacific Northwest (Hill, 2001; Mangan et al., 2024). Some farmers even opt to start Gilo seeds more than 12 weeks before transplanting, using individual pots for each plant instead of standard transplant trays; this is crucial as Gilo plants have the potential to grow much larger, with plant heights exceeding six feet being observed in Massachusetts under ideal conditions (Mangan et al., 2024). The extended period for starting S. aethiopicum seeds ensures that the plants have ample time to grow and develop before they are transplanted into the field; this approach allows for healthier and more robust plants, increasing the likelihood of a successful harvest (Mangan et al., 2024). Gilo is typically ready for harvest by late July under optimal conditions, providing a quick turnaround time from seed to harvest (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153).

2.3 Requirements for Optimal Growth and Development

Cultivating S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ for optimal growth requires careful consideration of climate, soil management, and water usage. Gilo requires well-drained soils with a pH range of 5.5-6.8 and moderate fertility levels to support healthy growth (Han et al., 2021; Hill, 2001; Lin et al., 2009, pp. 230–232). Water management is crucial for cultivating Gilo, necessitating irrigation at optimal intervals and depths to ensure the plant receives sufficient water for development (Han et al., 2021; Hill, 2001). Organic matter can aid in enhancing soil water retention capacity and reducing water loss through evaporation, thus promoting successful growth; planting of African eggplants involves land preparation by loosening the soil and incorporating well-rotted compost to create a nutrient-rich growing environment (Han et al., 2021; Maundu et al., 2023). Transplanting and spacing should be done carefully, with seedlings hardened off for about two weeks before transplantation and ensuring proper spacing to allow for healthy growth and development of the plants (Maundu et al., 2023).

3. ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY

3.1 Ecological Benefits of Cultivating S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’

Growing S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ in the Pacific Northwest could offer significant ecological and environmental benefits. The utilization of grafting techniques in vegetable production has been shown to improve yield, limit the effects of diseases like Fusarium wilt, enhance nutrient uptake, and improve water use efficiency (Nkansah et al., 2013). By grafting tomatoes onto African eggplant rootstocks, not only can crop productivity be increased, but the resilience of the plants to drought, salinity, and flooding can also be enhanced (Sabatino et al., 2019). Cultivating Gilo can contribute to biodiversity conservation and resilience in agricultural systems (Han et al., 2021; Lin, 2011). Additionally, African eggplant is known for its resistance to soil-borne diseases and pests, making it a valuable tool for crop protection in sustainable farming systems (Han et al., 2021; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Gilo’s diverse genetic makeup offers a range of traits and functions that can help protect against changing environmental conditions, such as extreme shifts in climate, pest outbreaks and pathogen transmission (Han et al., 2021; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153; Sabatino et al., 2019).

3.2 Urban Agriculture and Soil Conservation

African eggplant’s ability to thrive in limited spaces makes it suitable for urban agriculture, allowing for the conservation of soil fertility and maximizing landscape spaces (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Its aesthetic properties also make it a popular choice for ornamental and beautification purposes, and its partially shade-tolerant nature contributes to soil conservation by preventing erosion and maintaining soil fertility (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Additionally, growing African eggplant aids in soil conservation by covering bare areas between main crops and tolerating mild shade to coexist with taller plants (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Farmers can utilize regenerative cultivation techniques such as intercropping and mixed cultures, with examples of intercropping in Africa with crops like cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), sorghum, Indian jujube (Ziziphus mauritiana Lam), tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum), peppers (Capsicum annuum), West African sorrel (Corchorus olitorius), and okra (Abelmoschus esculentus); in mixed cultures, African eggplant serves as the main crop, while corn (Zea mays) and Yuca (Manihot esculenta) are grown as secondary crops (Han et al., 2021; Lin, 2011; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153).

3.3 Promoting Resilience in Food Production through African Eggplant Cultivation

In the face of climate change and increasing environmental challenges, the promotion of diversified agricultural systems, including the cultivation of underutilized crops like S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’, is crucial for building resilience in food production (Han et al., 2021; Lalhmingsanga et al., 2018, Lin, 2011). S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ is considered an “orphan crop”: a minor and/or underutilized crop that is not commonly traded internationally but often plays larger agricultural roles regionally (Swenson, 2022). Reintroducing orphan crops, such as African eggplant, into farming practices can help diversify the food system, provide nutritious options, and mitigate the impacts of climate-induced scarcities (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153; Swenson, 2022). By investing in the conservation and utilization of underused but nutrient-rich crops like Gilo, farmers can not only enhance food security and sustainability but also contribute to the preservation of agricultural biodiversity and the resilience of agroecosystems in the Pacific Northwest (Han et al., 2021; Lalhmingsanga et al., 2018; Lin, 2011; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153).

4. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL IMPLICATIONS

4.1 Meeting Demand for Ethnic Specialty Crops

By introducing and promoting the cultivation of S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ in the Pacific Northwest, local growers can not only meet the increasing demand for ethnic specialty crops but also address the barriers faced by immigrant and refugee populations in accessing culturally appropriate and fresh produce. The availability of these cultural foods can play a vital role in providing a sense of belonging, preserving cultural identity, and fostering connections within the community, particularly for individuals with lived refugee experiences who may be navigating significant life changes and challenges during resettlement (Gingell et al., 2022). According to Mary O. Hearst et al. (2021), chronic health inequities for communities of color are partially attributed to a lack of healthy preferred food access. Moreover, investing in the production and marketing of ethnocultural vegetables can create economic opportunities for small farmers while supporting the health and well-being of diverse immigrant communities in the region (Adekunle et al., 2012; Gingell et al., 2022; Hearst et al., 2021).

4.2 Social and Cultural Benefits of Growing S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’

Growing S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ in the Pacific Northwest, particularly in Seattle and King County, can offer significant social and cultural benefits to the diverse immigrant populations residing in the region (Mangan et al., 2008; Migration Policy Institute, 2014). With an estimated 2.1 million sub-Saharan African immigrants in the United States as of 2019, comprising 5% of the total foreign-born population, the demand for culturally relevant foods is on the rise (Lorenzi & Batalova, 2022). In the Seattle Municipal Area alone, there are approximately 65,000 African immigrants, highlighting the importance of catering to the culinary preferences and dietary needs of these communities (Migration Policy Institute, 2014). The United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants has observed the growth of refugee communities across the country engaging in the cultivation and sale of native crops, emphasizing the importance of promoting ethnocultural vegetables such as S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ (Mangan et al., 2008).

4.3 Bridging Cultural Heritage with Sustainable Agriculture

As demographic profiles continue to shift and the demand for diverse agricultural products grows, the cultivation of Gilo represents an opportunity to bridge the gap between cultural heritage and sustainable agriculture. By recognizing the significance of cultural foods in enhancing food security, promoting social inclusion, and celebrating culinary diversity, growers can contribute to a more vibrant and resilient food landscape (Gingell et al., 2022; Harper, 2018; Hearst et al., 2021). Embracing the cultivation of ethnocultural vegetables like S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ not only supports the dietary preferences of immigrant populations but also strengthens the cultural fabric of the community, fostering a more inclusive and interconnected food system in the Pacific Northwest (Adekunle et al., 2012; Gingell et al., 2022; Harper, 2018; Hearst et al., 2021).

5. HEALTH BENEFITS AND MEDICINAL USES

5.1 Nutritional Benefits of S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’

Cultivating S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ offers a multitude of benefits due to the nutritional content found in its leaves, which provide essential nutrients such as protein, fiber, calcium, iron, potassium, vitamin A, vitamin C, and various B-vitamins (Han et al., 2021; Lalhmingsanga et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2009, pp. 230–232; Maundu et al., 2023). The protein content supports muscle growth and repair, while fiber aids in digestion and weight management (Lalhmingsanga et al., 2018; Maundu et al., 2023). Additionally, the presence of calcium, iron, and other vitamins and minerals contribute to overall health by supporting bone strength, red blood cell production, immune function, and vision health (Lalhmingsanga et al., 2018; Maundu et al., 2023). Furthermore, Solanum aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ leaves contain phytochemical compounds with antioxidant properties, anti-inflammatory effects, and metabolic benefits, making them a valuable addition to a balanced diet (Ienciu et al., 2022; Maundu et al., 2023).

5.2 Medicinal Uses in Indigenous African Medicine

In addition to its nutritional benefits, S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ has a long history of use in indigenous African medicine for various ailments (Daunay et al., 2000; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). An alcohol extract of leaves is used as a sedative, anti-emetic, and to treat tetanus after miscarriage and abortion (Yang & C. Ojiewo, 2013). The roots, fruits, and leaves of the plant have been used as carminatives, sedatives, and treatments for conditions like high blood pressure, colic, and uterine complaints (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2024; Lalhmingsanga et al., 2018; Yang & C. Ojiewo, 2013). Fruits of bitter cultivars have been utilized for their analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and other medicinal properties (Ienciu et al., 2022; Yang & C. Ojiewo, 2013). These medicinal uses highlight the versatile nature of ‘Gilo’ beyond its culinary appeal, highlighting its value in traditional healing practices.

5.3 Health Benefits and Metabolic Effects

Studies have shown that many tropical species of eggplant, including S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’, have positive metabolic effects when consumed regularly (Daunay et al., 2000; Essien et al., 2021; Ienciu et al., 2022; Lalhmingsanga et al., 2018). Gilo causes significant improvement in some blood parameters, including packed cell volume, white blood cell counts, and overall blood platelet counts (Daunay et al., 2000; Essien et al., 2021). Compounds found in eggplants, such as amides and alkaloids, exhibit antibacterial and antioxidant properties that may aid in combating various health issues (Lalhmingsanga et al., 2018). The functional nutrients and phytochemicals present in S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ offer a broad range of health benefits, making it a valuable addition to both culinary dishes and traditional medicinal practices (Ienciu et al., 2022). Cultivating Solanum aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ in the Pacific Northwest would not only provide a diverse range of essential nutrients and potential health benefits but also offer a unique opportunity to integrate traditional indigenous African medicinal practices with modern dietary needs, making it a valuable addition to local agriculture and culinary traditions while promoting holistic well-being and nutritional diversity.

6. ECONOMIC AND MARKET POTENTIAL

6.1 Market Potential of S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’

The cultivation of S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ in the Pacific Northwest presents a promising avenue for farmers to tap into the rising demand for novel produce and nutritious food and is increasingly sought after by consumers interested in diverse and culturally significant vegetables, creating a lucrative market opportunity in the region (Adekunle et al., 2012; Govindasamy et al., 2010; Maynard, 2016).

6.2 Success Stories and Economic Opportunities

Success stories like that of Janine Ndagijimana, who transformed her small-scale African eggplant farming venture in Vermont into a flourishing business through strategic marketing and community engagement, underscore the economic potential of cultivating Gilo in response to evolving market trends (Dierking, 2018). The USDA’s Sustainable Agriculture, Research, and Education (SARE) program has also taken an interest in small scale African eggplant production and has awarded grants to farmers seeking to cultivate S. aethiopicum in the United States (Doucoure, 2022; Kragnes, 2023). Furthermore, insights from a UMass study estimating the production costs of “ethnic” eggplant varieties at $6000 per acre provide valuable guidance for farmers looking to venture into growing S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ (Maynard, 2016). By understanding these cost estimates and production considerations, farmers can make informed decisions about resource allocation, cultivation strategies, marketing channels, and financial planning to optimize profitability (Govindasamy et al., 2010; Mangan et al., 2024). Integrating these research findings into the argument for growing Gilo in the Pacific Northwest would enable farmers to navigate the complexities of agribusiness, mitigate risks, and capitalize on emerging market opportunities effectively.

6.3 Research-Driven Approach to Economic Feasibility

By adopting a research-driven approach to evaluating the economic feasibility of introducing new crops like Gilo to the market, farmers can harness the full economic potential of Gilo (Adekunle et al., 2012; Govindasamy et al., 2010). Understanding production costs, market demand trends, and success stories in the industry provides a comprehensive framework for farmers to enhance profitability, foster agricultural innovation, and drive economic growth in the region’s farming communities (Adekunle et al., 2012; Mangan et al., 2008). This strategic and data-driven approach, combined with the growing consumer interest in diverse and nutritious vegetables, positions S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ as an asset in the agricultural landscape of the Pacific Northwest, offering both economic opportunities for farmers and flavorful, culturally significant produce for consumers (Govindasamy et al., 2010; Mangan et al., 2008).

7. POTENTIAL FOR SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

7.1 Genetic Enhancement and Plant Breeding of S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’

The scientific study of S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ in the Pacific Northwest can provide valuable insights into its agronomic characteristics, nutritional content, and potential medicinal properties (Daunay et al., 2000; Han et al., 2021; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153; Yang & C. Ojiewo, 2013). Despite receiving little production research, African eggplants show excellent potential for genetic enhancement through simple selection, plant breeding, and potentially hybridization (Daunay et al., 2000; Han et al., 2021; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). Research into enhancing African garden eggs for increased yield, disease resistance, and diverse fruit characteristics can help create varieties better suited to specific growing conditions in the region (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153; Yang & C. Ojiewo, 2013). By tapping into the genetic diversity of Gilo and leveraging advancements in biotechnology, breeders can potentially develop new varieties with enhanced traits, such as resistance to pests, diseases, and environmental stresses (Daunay et al., 2000; Han et al., 2021; Nkansah et al., 2013; Yang & C. Ojiewo, 2013).

7.2 Potential as Genetic Resource for Improving Global Crops

S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’s genetic closeness to major global crops in the Solanaceae family, such as tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, and eggplants, opens possibilities for using African eggplants as a genetic resource to improve these crops (Daunay et al., 2000; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). The discovery of resistance traits in African eggplants, such as resistance to atrazine, tobacco mosaic virus, and various pathogens, can potentially be harnessed to enhance the disease resistance of other important crops (Han et al., 2021; National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). The potential use of African eggplants for controlling pests and diseases in commercial crops underscores the broader applications and ecological benefits that this crop could offer to agricultural systems in the Pacific Northwest (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153).

7.3 Advancing Agricultural Knowledge through Scientific Research

Scientific exploration into S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ in the Pacific Northwest holds immense promise for advancing agricultural knowledge, improving crop productivity, and promoting sustainable farming practices (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153; Yang & C. Ojiewo, 2013). By delving into the genetic diversity, agronomic traits, and potential applications of African eggplants, researchers can pave the way for innovative breeding programs, biotechnological advancements, and enhanced agronomic practices (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 137–153). The research findings and genetic resources derived from studying African eggplants can contribute to the overall resilience, diversity, and sustainability of agricultural systems in the Pacific Northwest and beyond (Daunay et al., 2000; Han et al., 2021).

CONCLUSION

The cultivation of Solanum aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ in the Pacific Northwest presents a distinct opportunity for farmers in the region to tap into the growing market demand for novel produce and culturally significant vegetables. While the crop may require extra attention and care due to its unique characteristics, including its flavor profile, nutritional benefits, and cultural significance, the potential economic benefits make it a valuable addition to local agriculture. By leveraging research-driven insights and the success stories of small-scale growers, farmers can navigate the challenges and opportunities associated with growing S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’ effectively.

To maximize the value of cultivating Gilo in the Pacific Northwest, it is essential to consider factors such as its environmental impact, social and cultural implications, and economic viability. Through strategic planning, resource optimization, and innovative cultivation practices, farmers can enhance the crop’s economic potential while promoting sustainable agriculture and preserving cultural heritage. Research and innovation will play a crucial role in advancing knowledge and practices related to growing S. aethiopicum ‘Gilo’, enabling farmers to capitalize on its unique attributes and meet the evolving market demand for diverse and nutritious vegetables. By embracing this crop and its benefits, the Pacific Northwest can further diversify its agricultural landscape, foster economic growth, and offer consumers a flavorful and culturally enriching produce option.

REFERENCES

Adekunle, B., Filson, G., & Sethuratnam, S. (2012). Culturally appropriate vegetables and economic development. A contextual analysis. Appetite, 59(1), 148–154. Science Direct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.003

Daunay, M. C., Lester, R. N., Hennart, J. W., & C. Duranton. (2000). Eggplants: present and future. HAL (Le Centre Pour La Communication Scientifique Directe), 19, 11–18. Research Gate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341855441_Eggplants_present_and_future

Dierking, P. (2018, August 19). Refugee Grows African Eggplants in US (H. Do, Ed.). Voice of America – Learning English; Voice of America. https://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/refugee-grows-african-eggplant-in-us/4526887.html

Doucoure, K. (2022). Assessing Financial Feasibility of African Eggplant Production – SARE Grant Management System. Projects.sare.org; SARE. https://projects.sare.org/sare_project/fne21-978/

Essien, N. M., Nwangwa, J. N., Mfem, C. C., Uket, J. M., & Archibong, E. A. (2021). Effect of Solanum gilo leaf extract on some haematological indices of albino Wistar rats. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 12(1), 108–111. https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2021.12.1.0463

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2024). African garden egg. FAO; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/traditional-crops/africangardenegg/en/

Gingell, T., Murray, K., Correa-Velez, I., & Gallegos, D. (2022). Determinants of food security among people from refugee backgrounds resettled in high-income countries: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. PLOS ONE, 17(6), e0268830. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268830

Govindasamy, R., van Vranken, R., Sciarappa, W., Ayeni, A., Puduri, V. S., Pappas, K., Simon, J. E., Mangan, F., Lamberts, M., & McAvoy, G. (2010). Ethnic crop opportunities for growers on the east coast: a demand assessment. The Journal of Extension, 48(6), 1–9. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3393&context=joe

Han, M., Opoku, K. N., Bissah, N. A. B., & Su, T. (2021). Solanum aethiopicum: The Nutrient-Rich Vegetable Crop with Great Economic, Genetic Biodiversity and Pharmaceutical Potential. Horticulturae, 7(6), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7060126

Harper, A. (2018, July 16). Food access and culture: What it means for immigrant and refugee populations. Www.canr.msu.edu; Michigan State University. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/food-access-and-culture-what-it-means-for-immigrant-and-refugee-populations

Hearst, M. O., Yang, J., Friedrichsen, S., Lenk, K., Caspi, C., & Laska, M. N. (2021). The Availability of Culturally Preferred Fruits, Vegetables and Whole Grains in Corner Stores and Non-Traditional Food Stores. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5030), 5030–5030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18095030

Hill, D. E. (2001). Specialty crops: okra, leek, sweet potato and jilo. Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. https://archive.org/details/specialtycropsok00hill/page/n1/mode/2up

Ienciu, A., M. Cărbunar, & Vidican, O. (2022). THE FUNCTIONAL NUTRITIONAL VALUE AND THE HEALTH BENEFITS OF CONSUMING EGGPLANT (pp. 41–46). University of Oradea. http://protmed.uoradea.ro/facultate/publicatii/protectia_mediului/2022A/hort/01.%20Ienciu%20Andrada.pdf

Kragnes, V. (2023). Expanding Production of African Eggplant in the Red River Valley – SARE Grant Management System. Projects.sare.org; SARE. https://projects.sare.org/sare_project/fnc22-1336/

Lalhmingsanga, Pandey, A. K., Angami, T., & Chhetri, A. (2018). The sweetness of bitter brinjal (Solanum gilo Raddi): An underutilized vegetable of Northeastern Himalayas. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies, 6(2), 7-08. https://www.plantsjournal.com/archives/2018/vol6issue2/PartA/6-1-35-867.pdf

Lin, B. B. (2011). Resilience in Agriculture through Crop Diversification: Adaptive Management for Environmental Change. BioScience, 61(3), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2011.61.3.4

Lin, L., C. George Kuo, & Hsiao, Y. (2009). Discovering Indigenous Treasures (pp. 230–232). AVRDC – World Vegetable Center. https://avrdc.org/african-eggplant-solanum-aethiopicum/

Lorenzi, J., & Batalova, J. (2022, May 11). Sub-Saharan African Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/sub-saharan-african-immigrants-united-states#distribution

Mangan, F. X., Mendonça, R. U. de, Moreira, M., Nunes, S. del V., Finger, F. L., Barros, Z. de J., Galvão, H., Almeida, G. C., Silva, R. A., & Anderson, M. D. (2008). Production and marketing of vegetables for the ethnic markets in the United States. Horticultura Brasileira, 26(1), 6–14. SciELO Brazil. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-05362008000100002

Mangan, F., Barros, Z., & Marchese, A. (2024). Jiló | WorldCrops. World Crops for Northern United States; UMass Amherst Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment. https://worldcrops.org/crops/jilo

Maundu, P., Kioko, J., Munene, C., & Hunziker, M. (Eds.). (2023, November). African Eggplant (New) | Infonet Biovision Home. Infonet-Biovision.org; Infonet Biovision. https://infonet-biovision.org/indigenous-plants/african-eggplant-new#5

Maynard, A. A. (2016). Specialty Eggplant Trials 2010-2012. The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/CAES/DOCUMENTS/Publications/Bulletins/B1043pdf.pdf

Migration Policy Institute. (2014, February 4). U.S. Immigrant Population by State and County. Migrationpolicy.org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/us-immigrant-population-state-and-county?width=1000&height=850&iframe=true

National Research Council. (2006). Lost Crops of Africa: Volume II: Vegetables (pp. 137–153). National Academies Press. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/download/11763

Nkansah, G. O., Ahwireng, A. K., Amoatey, C., & Ayarna, A. W. (2013). Grafting onto African eggplant enhances growth, yield, and fruit quality of tomatoes in tropical forest ecozones. Journal of Applied Horticulture, 15(1), 16–20. horticultureresearch.net. https://horticultureresearch.net/jah/2013_15_1_16_20.PDF

Sabatino, Iapichino, Rotino, Palazzolo, Mennella, & D’Anna. (2019). Solanum aethiopicum gr. gilo and Its Interspecific Hybrid with S. melongena as Alternative Rootstocks for Eggplant: Effects on Vigor, Yield, and Fruit Physicochemical Properties of Cultivar ′Scarlatti′. Agronomy, 9(5), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9050223

Swenson, S. (2022, June 28). Why We Need to Adopt More Orphan Crops. Modern Farmer. https://modernfarmer.com/2022/06/adopt-more-orphan-crops/

Yang, R. Y., & C. Ojiewo. (2013). African Nightshades and African Eggplants: Taxonomy, Crop Management, Utilization, and Phytonutrients. Acs Symposium Series, 137–165. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259620209_African_Nightshades_and_African_Eggplants_Taxonomy_Crop_Management_Utilization_and_Phytonutrients